The Oregon Jewish Museum and the Holocaust Education Center displayed strips of ripped cloth bearing the names of Syrian detainees in the prisons of the Syrian regime, on the west coast of the United States of America, over a period of two years.

“Human Rights After the Holocaust” is the first exhibition of its kind in the Pacific Northwest and one of a few nationally that takes on human rights not just through archival photos and first-person interviews with recent refugees from Afghanistan, Ukraine, Tigray, Darfur, to name a few, but also through loaned objects from Syria, Rwanda, Bangladesh, Cambodia, and the US. Mansour al-Omari, a Syrian human rights activist imprisoned in Damascus in 2012, loaned OJMCHE an extraordinary item, according to the Art Daily magazine.

The ripped cloth returned again to the United States after it was displayed in the “People’s Court” and “Move the Wheels of Justice” museums in the Dutch city of The Hague, the headquarters of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and the Mediterranean Museum in the Swedish capital, Stockholm.

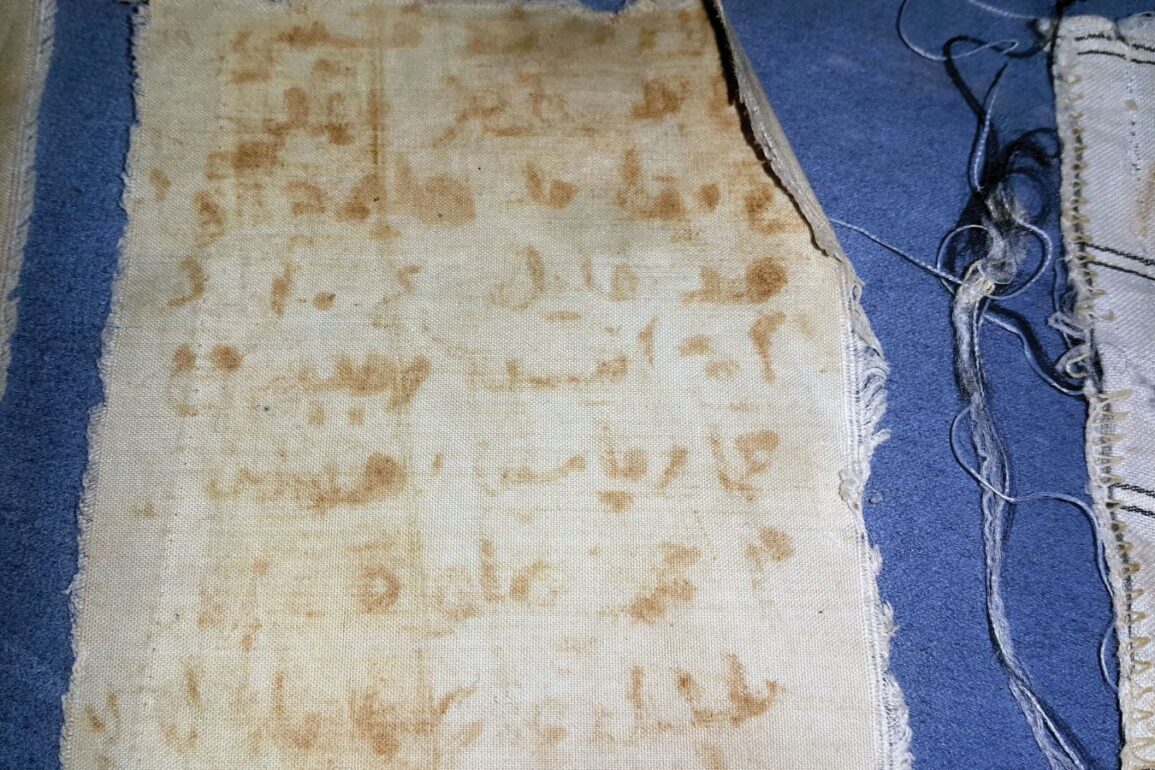

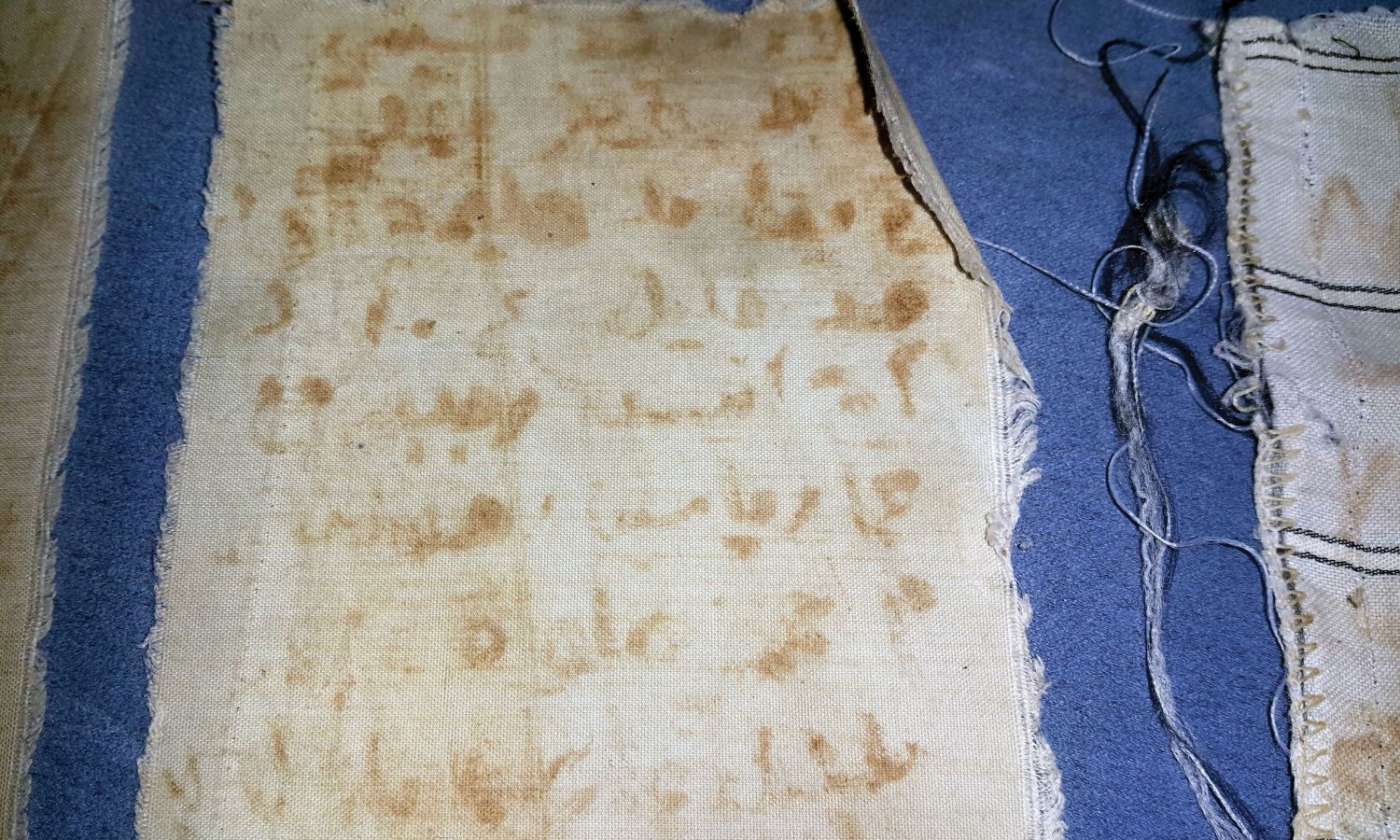

Prior to that, al-Omari’s ripped cloth with the names of 82 fellow prisoners written in blood and rust in 2012 was displayed in the “Syria, Please Don’t Forget Us” exhibition at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, where it was displayed for more than two years.

The importance of the five strips of ripped cloth, which al-Omari lent to the museum, stems from their being an illustration of the horrors that Syrian detainees are subjected to in the prisons of the Syrian regime, according to what al-Omari told Enab Baladi.

Names written in blood and rust

“When (Mansour) al-Omari heard that he was to be released, he and other inmates used a mixture of blood and rust to write the names of 82 fellow prisoners on five strips of ripped cloth (in 2012). Omari smuggled the list out of prison and contacted the families of the prisoners to tell them that they were alive and where they were being held. Of the 82 prisoners, only four are known to be safe,” the Art Daily said.

Al-Omari and his companions wrote the names of the detainees with rust and blood using chicken bones, and there was no other way to write them and then smuggle them from an underground prison of the Syrian regime on five pieces of cloth.

The detainees advocate said that he called their families to tell them where they were arrested and that they were alive, and he knew that four detainees were safe.

Five strips of ripped cloth that al-Omari smuggled the list out of prison and contacted the families of the 82 prisoners to tell them that they were alive and where they were being held – (Enab Baladi/ Mansour al-Omari)

Exhibitions are a tool for raising the issue of detainees

“Museums and galleries are spaces for dialogue, providing spaces for dialogue between members of the public in all their diversity and allowing them to participate actively and directly,” said Judy Margles, director of the Jewish Museum of Oregon and the Holocaust Education Center, in describing the opening of the exhibition.

She added, “Museums also play an exceptional role by raising contemporary issues, educating visitors and informing them about human rights violations and mass atrocities, using their creative tools, including videos, photos, music, live testimonies and evidence of crimes, which can directly influence the public and contribute to shaping public opinion and strengthen it.”

Margles spoke of how amazing it was to watch visitors read, listen and comprehend, look at the shirt pieces, and ask questions, sometimes even shedding tears.

“The strips of ripped cloth are the star of this exhibition, and I am truly grateful for your trust in the museum,” concluded the director of the Oregon Jewish Museum.

According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), no less than 1,047 people were arrested in Syria during the first half of 2023 at the hands of various parties to the conflict in Syria, of which 501 were detained by the Syrian regime forces, while the total number is 155,243, since 2011, 135,481 of them are detained by the regime.

Al-Omari told Enab Baladi that the exhibition is an opportunity to shed light on the issue of detainees and torture in Syria and contributes to presenting facts to different segments of society, including school and university students, academics, the media, and politicians.

Also, the exhibition shows the horrors that detainees and Syrians, in general, are subjected to, which pushes them to flee the country and seek safety and security in other countries as refugees.

Also, the continued presentation of evidence of Bashar al-Assad’s crimes against Syrians, and their viewing by the public in its various sects and specializations, prevent these crimes from being forgotten or neglected and impedes the fading of the Assad regime’s image as the perpetrator of the most horrific crimes in this century.

The presentation of the ripped cloth comes at a sensitive circumstance that the file of the Syrian detainees is going through following the recent Arab rapprochement with the Syrian regime, which makes the movement of the detainees’ families narrow to resolve this issue.

As much as museums and galleries play a role in culture and history, but in the case of displaying canvases, they play a different and exceptional role by raising contemporary issues.

Al-Omari told Enab Baladi that museums and galleries that allow their visitors to communicate directly with culture also inform them of human rights violations and mass atrocities using their creative tools, including video recordings, photos, music, live testimonies, and evidence of crimes.

In conjunction with the pieces of cloth, al-Omari’s testimony about torture in Assad’s prisons, and the story of the strips of ripped cloth and the conditions of the detainees, are shown.

Second exhibition after “Syria, Please Don’t Forget Us”

In 2017, the Holocaust Museum in Washington also borrowed the shirt from al-Omari and displayed it for American citizens, including the candidate for the presidency of the United States in the elections at the time, Nikki Haley, who served as United States ambassador to the United Nations at the time.

The museum also displayed a mobile phone and a “USB” device used by the Syrian military police photographer, known as “Caesar,” to leak 55,000 photos of torture victims in Branch “215,” affiliated to the Syrian Military Security.

Nikki Haley then gathered members of the Security Council and visited the exhibition with them before addressing the Security Council by saying that everyone had seen undeniable evidence of Assad’s atrocities and human rights violations, and Washington cannot and should not forget the Syrians.

Before his release from prison in 2012, the detainees gathered around al-Omari to bid him farewell while saying, “Please do not forget us.” This phrase was the title of that exhibition, al-Omari said.

Nikki Haley, former United States ambassador to the United Nations, visits the exhibition “Syria, Please Don’t Forget Us” at the Holocaust Museum (The Holocaust Museum)

Nikki Haley, former United States ambassador to the United Nations, visits the exhibition “Syria, Please Don’t Forget Us” at the Holocaust Museum (The Holocaust Museum)

On June 29, the United Nations General Assembly voted in favor of a draft resolution establishing an international institution to clarify the fate of missing persons in Syria.

According to the report, the association agreed to establish a new international institution to clarify the fate of the missing and their whereabouts in Syria and to provide adequate support to the victims, survivors, and families of the missing.

The draft resolution was supported by 83 countries, while 11 countries voted against it, and 62 countries abstained from voting.

Among the Arab countries, Qatar and Kuwait voted in favor of the project, while Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Oman, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Lebanon, Tunisia, and Yemen abstained.

The draft resolution was co-authored by Luxembourg, Albania, Belgium, Cape Verde, the Dominican Republic, and Macedonia.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.