Ken Ird and Kristiina Tiideberg, current and former curators of the University Museum, have compiled the book “The Stories of the University of Tartu Karcher” after several years of research, going through archival sources, historical documents and contemporary memories. The university ‘prison’ chambers are as old as the university itself. The book’s authors give some background information about that as well.

First, the Academia Gustaviana was established in Tartu, where the Jesuit seminary provided a fertile educational environment. As was customary at the period, the newly established institution was given its own jurisdiction, including the right to prosecute minor offenses.

To keep students on the straight and narrow, ascetic places of repentance were attached to universities as well, where sinners were sent to contemplate on their lives for a shorter or longer period of time. The first known location of the prison, with three small detention rooms, was in a 1642 building opposite St. John’s Church. It was inspired by the University of Uppsala.

Sins worthy of quarantine

In universities of the 19th century, the lightest forms of punishment was a reprimand from the rector or the university court, which was followed by a detention. It was worse if you received a reprimand from the university council, a reduced scholarship, or your name appeared on the blackboard in the main university building.

However, it was quite a tough story when a student who broke the rules was deprived of his scholarship altogether, de-registered or even forbidden to apply for further studies at Tartu or, in special cases, at another university of the Russian Empire. In the case of really serious offenses, the university handed the offender over to a criminal court.

As a result, it was rather usual for students to wind up in a detention cell in the main building’s attic. “In the period 1802-92, a total of 6,600 Tartu University students were sentenced to detention,” the authors write. Statistics from 1802 to 1827 show that theology students were the most decent and undergraduates were the least.

So, what were the students who were detained up to? According to the two surviving punishment records (1875-1892), the most prevalent reasons for punishment were disorderly conduct (424 times), fighting, illegal borrowing of money and resisting authorities. Less frequently, it was a result of firing guns, smashing windows, breaking lamps, and (NB!) failing to return library books. There were only five arrests for dueling – almost as few as for driving in circles, singing and smoking on Toom Hill.

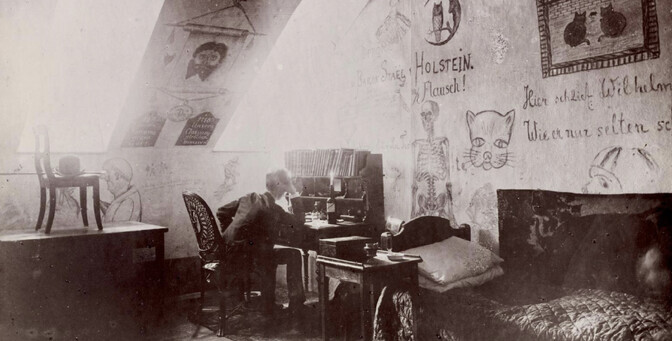

Those who have been in the cells have reported that it was damp as hell in the summer, and that in the winter they had to walk and stamp their feet to stay warm. It is remembered, however, as a somewhat habitable space; for example, in 1802, the furniture comprised a bed, a table, a chair, a mattress, and a bell to summon a “pedell” (an academic policeman appointment to assist the rector). For a longer stay, you could bring your own laundry, bed linen, and textbooks, as well as furniture. Students having an excellent rapport with the pedal could even order some treats for a few pennies.

Prominent sitters

A number of men who later made their names in history have spent time within the walls of the university prison. Kristian Jaak Peterson, for example, was nabbed with his fellow theology student Ferdinand Friedrich Vierhuff on the night of 30 July 1819 for “disorderly conduct.” Rector Gustav Ewers and the university court sentenced the young men to two days of detention for staying out too late with the explanation that “otherwise such a useful and beautiful morning would be wasted!”

On the other hand, Georg Philipp von Oettingen, later rector of the University of Tartu (1868-1876) and mayor of Tartu (1878-1891), was sentenced to two weeks’ imprisonment for taking part in a riot against Ludwig Preller, professor of classical philology and director of the university’s art museum. Notably, Preller expelled a student for failing to translate a seminar section and jokingly observed to the rebellious student, “Caput tenens grave est” (“it is difficult to keep one’s head”), alluding to a hangover.

An offended student challenged the professor to a duel, who refused, he gathered his friends and whistled the professor out of the lecture, throwing apples and stuff at him. Five of the students involved in the protest were thrown out of the university, while the rest had to spend a week or two in cells on bread and water. Von Oettingen and his friend Alexander von Freimann spent this time in the old anatomy room, because there were so many rebels that the auditoriums had to be used as barracks. For entertainment, they gave each other music lessons on guitar and clarinet.

The benefits of isolation

During the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the university cells were less and less used, and after the opening of the Estonian-language university in 1919, they was closed for good. The rooms under the roof were used as a museum and later as a storage space.

In the 1965 fire of the main building, the rooms were also severely damaged. One of the five former chambers, the best-preserved, was restored by the restorers of the Leningrad Hermitage only in 1978. Since then, it has been part of the University Museum’s exhibition.

As far as is known, the poet Hannes Varblane, who was a fourth-year history student at the time and who was accused of organizing an “orgy” by the “old-fashioned commandant fraternity” of Pälson’s unit, was the last person to be sentenced to detention in 1973, as Varblane wrote in his 2010 short story “The Attic of Tartu University.”

Dean Benjamin Nedzvetski, or Bendzi, was described as a good man who offered the offender a choice of punishment to avoid an ex-matriculation. Like a ray of light in the darkness, Varblae remembered the kartser and proposed it to the dean, saying, “Lock me up for three weeks like Kristjan Jaak in his day.” Nedzvetski approved of the plan, but because the storage facility had burned down, he placed Varbla under house arrest for three weeks, with all bills paid. Varblane completed his examinations and graduated at the end of the story.

—

Follow ERR News on Facebook and Twitter and never miss an update!

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.