The state’s Department of Corrections scrambles to get its story straight, and book donors don’t know how to proceed.

Please note: This report is a follow-up to our September 25 story on book restrictions in Wisconsin prisons. Since we first published this story, we have added an extensive update to it. The update details a reporting error on my part, and addresses various points of confusion over the Wisconsin Department of Corrections’ restrictions on the work Wisconsin Books to Prisoners. We recommend reading that story and its update first. —SG

The Wisconsin Department of Corrections (DOC) has changed a policy that governs book donations to prison libraries. The new language in the policy further restricts donations of used books and removes a provision explaining which donations prison libraries can accept. In fact, state prison officials have changed this policy twice in the past few weeks—once in late September, then again in October, after Tone Madison asked an agency spokesperson about the meaning of the new library policy language.

The hasty policy revisions are the latest and strangest twist in DOC’s struggle to justify its tightening restrictions on prisoners’ access to books, or even explain its current rules. Throughout late September and early October, DOC faced renewed media scrutiny of its restrictions on books mailed directly to prisoners. Madison-based group Wisconsin Books to Prisoners (WBTP) has believed that, since mid-August, the DOC is prohibiting it from directly mailing any books to incarcerated people. In response, DOC spokesperson Beth Hardtke has responded by repeatedly asserting that WBTP is barred only from sending used books but can still send in new ones. DOC officials have repeatedly claimed that they need to crack down on used books in order to keep contraband out of prisons, citing the dangers fentanyl and other substances pose to prisoners and staff alike. However, DOC hasn’t provided clear data to illustrate whether or not used books serve as a significant conduit for contraband.

DOC has attempted to deflect concerns about the book restrictions by touting the access Wisconsin prisoners have to libraries and other resources. In a September 30 email, Hardtke sent a group of reporters photos of the libraries at two state prisons—”to show you that books are indeed available in our facilities,” she wrote. This isn’t really an answer to the complaints advocates have raised. WBTP and like-minded groups around the country don’t claim that prisoners have no access to books. Rather, they complain that prison systems limit that access through arbitrary censorship, bureaucratic obstacles, and financial barriers. They also don’t dispute the fact that smuggled drugs can present a lethal threat in prisons. Instead, these groups argue that restricting books isn’t the right way to address that threat.

Meanwhile, WBTP says it’s getting mixed signals from the DOC. Co-founder Camy Matthay is reluctant to start sending books again—and potentially waste WBTP’s scarce resources—until she gets direct clarification from DOC officials.

“We’re not going to ship books [for the time being],” Matthay says. “I’m convinced they’ll come right back.”

The DOC reinstated its prohibition on used books in direct-to-prisoner mail in January 2024. Matthay exchanged emails with several DOC officials over the next seven months, urging them to change course. Sarah Cooper, Administrator of DOC’s Division of Adult Institutions, responded on August 16 via email. Cooper wrote in that email that “the decision was made to no longer allow books in from your organization.” Matthay interpreted this as DOC escalating to a total ban on WBTP book shipments. She says DOC did nothing to correct or clarify that reading until after WBTP went public about the new restrictions in a September 17 social media post. A Wisconsin State Journal story posted on September 20 reported that WBTP “has been barred from the state’s facilities,” also portraying this as a blanket ban. While DOC has since responded to reports on the ban by stating that it is a prohibition on used books only, the initial message did not make any such distinction.

Matthay insists that since then, she has kept following up with DOC officials, but has not received any direct communication from them clarifying that WBTP can still send in new books. She says that a couple of DOC officials have reached out to her looking to set up further conversations about the dispute. But, as for DOC’s assurances that this is only about used books, Matthay says she has only heard those claims secondhand through media reports.

“They haven’t told us anything,” Matthay says.

WBTP is still seeing plenty of unmet demand for books.

“We are still getting 50 letters a week or so from prisoners requesting books and it bothers us that some of these prisoners have to work about six hours to buy a first-class stamp,” Matthay notes.

As WBTP remains stalled, the DOC is also tightening its limitations on the books prisoners can access via prison libraries.

Bans on two fronts

Rules governing the materials prison libraries can accept are a technically distinct policy matter from books mailed directly to prisoners. DOC’s library-book restrictions were more permissive, at least officially, until the end of September 2024. In the eight months after DOC reinstated its prohibition on mailing used books to prisoners, DOC libraries accepted donations of used books. Those included 10 boxes of used books from a Fox Valley non-profit, ESTHER, sent to Waupun Correctional Institution in August. In her September 30 email to reporters, Hardtke acknowledged that “Individual wardens and librarians also [previously] had discretion to accept used books from certain trusted sources for donation to the institution libraries.”

Hardtke went on to explain: “In January, DOC announced that it could no longer accept used books from anyone—including Wisconsin Books to Prisoners—and that policy is now being enforced when it comes to library donations as well (sic) books sent to persons in our care.” (Underline Hardtke’s; “persons in our care” is DOC’s official euphemism for the people it incarcerates.) This statement conflates two separate changes to DOC policy—which took place eight months apart—as if they happened in tandem, under the same rationales.

What DOC decided in January was to stop making exceptions to a long-standing policy stipulating that “Inmates may only receive publications directly from the publisher or other recognized commercial sources in their packages.” This DOC policy deals specifically with mail that prisoners receive. It doesn’t necessarily restrict what DOC can receive and make available to prisoners through libraries.

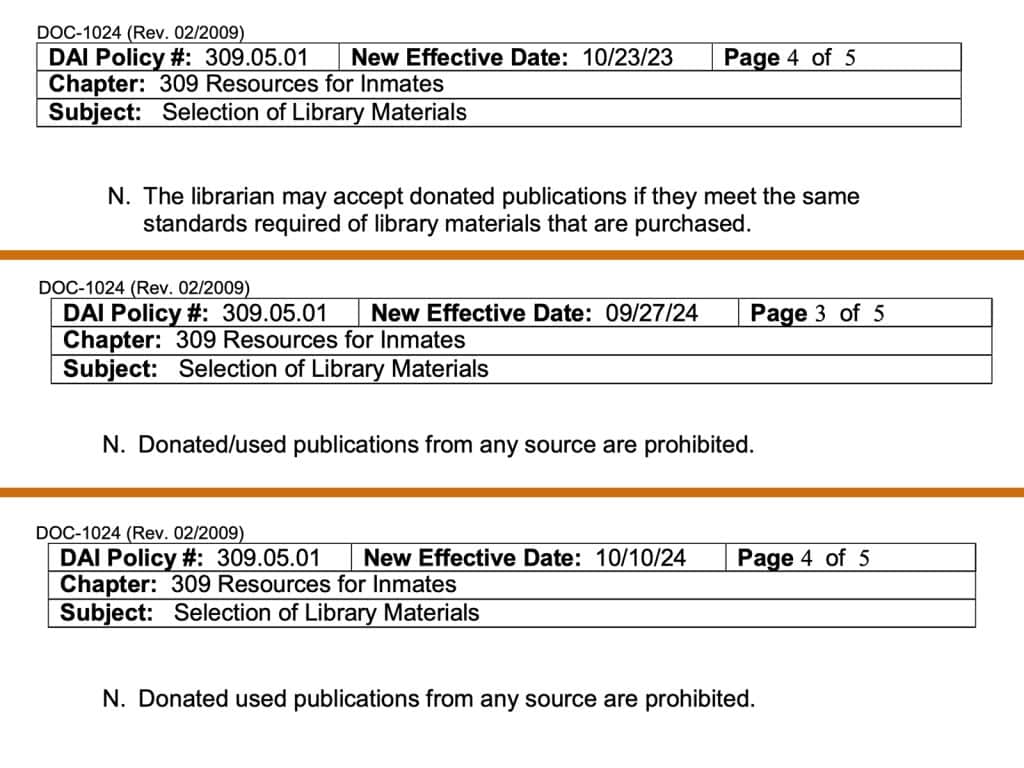

The DOC’s Division of Adult Institutions sets out guidelines for acquiring prison library materials in Chapter 309 of its Policies and Procedures. Until recently, this policy allowed state prison libraries to accept donated materials: “The librarian may accept donated publications if they meet the same standards required of library materials that are purchased.” (In the state’s Administrative Code for DOC, the definition of publications includes “books, magazines, newspapers, and pamphlets.”) In other words, this language did not set any specific restrictions on donated books. Prison librarians still had to follow a number of restrictions for book selections—prohibitions on materials deemed “pornographic,” materials advocating violence or illegal activities, and so on—but could, affirmatively, take donated books.

DOC officials last month adopted an updated version of the policy, setting an effective date of September 27, 2024, which put new restrictions on donated library books. This revision stripped out language that allowed donated materials and replaced it with a new provision: “Donated/used publications from any source are prohibited.”

On the surface, it was not clear whether this language banned donations of used materials only, or donated materials generally, whether new or used. The forward slash in “Donated/used” created ambiguity. A forward slash can denote a separation between alternatives in a sentence, or indicate some other link between concepts. Whether DOC intended the slash to serve as a stand-in here for “or,” a stand-in for “and,” or something else, the meaning of the provision could vary. In making this change, DOC didn’t add any new language specifying under what conditions donated publications can be accepted.

Tone Madison asked DOC to clarify the meaning of the new rule in an October 8 email to department spokesperson Beth Hardtke. DOC did not reply. But the DOC did quietly change the policy. DOC’s website on the morning of October 10 reflected yet another updated version of the policy, effective that day, which removed the forward slash. It now reads: “Donated used publications from any source are prohibited.” This update, like the September 27 policy, lacks any other language about donated library materials. It still doesn’t specify what sorts of donated materials are allowed, just that used materials are not allowed. In any case, the removal of just one punctuation mark makes the policy clearer and arguably changes its meaning entirely.

Versions of the policy from before the revisions, after the September 27 revision, and after the October 10 revision show the changes.

Hardtke did not respond to a follow-up request for comment after the most recent change, either. Governor Tony Evers’ office referred a request for comment back to the DOC.

The enactment of the new library policy was news to Fran Nelson, a volunteer with ESTHER. The Neenah-based interfaith social-justice group began donating books to Wisconsin DOC libraries in late 2020. Nelson says that ESTHER has donated about 3,500 books to about a dozen prison libraries around the state. She reports that only one prison has turned away the group’s book donations during that time. In February 2024, state purchasing regulations thwarted ESTHER’s attempt to acquire thousands of discarded books from a UW-Green Bay library and donate them to prisons. To Nelson’s great frustration, the state instead auctioned the books off. Otherwise, she says that her donation efforts have run into few snags until recent weeks.

“The [DOC] librarians are wonderful to work with, and no one has ever suggested that any problem has arisen in any way from any of the books that we’ve given—except, ‘Would you send us more?’” Nelson says.

She points out that, in the four years since the project began, “I never pretended that we were focusing on new books.” ESTHER has instead focused on donating used books in good condition, most of them donated through the Half Price Books chain.

The first sign of real trouble for ESTHER’s prison books program came over the past few months. Nelson says ESTHER recently brought a shipment of about 350 books to one of DOC’s maximum-security facilities—one that has accepted the organization’s donations in the past—but was later informed that the facility could not accept them. (Nelson declined to name the specific prison on the record, citing concern for DOC personnel who have helped the group.) “We had to come and pick them up, because the librarian was told that the used books were not allowed and she had to remove them,” Nelson says. “We went down a few days ago and collected the 10 boxes and re-donated them to small public libraries that wanted to increase their collections.”

Even then, Nelson didn’t realize that DOC had actually adopted a new policy banning used-book donations (and arguably all library donations, depending how one reads the policy at different points in time). Nelson only got confirmation of the library donation policy secondhand, during an interview for this story. Like Matthay, she says she’s received no direct communication from DOC officials about recent changes impacting her work, despite the rapport she’s built with various DOC employees over the years.

“I would like to sit down and talk with them and watch what they can come up with when they are asked, ‘What is the risk of a book donated to your library reaching a prisoner with drugs?’” Nelson says.

Anatomy of a clusterfuck

So far, DOC has yet to answer that question. In response to multiple press inquiries, Hardtke has offered some hard-to-parse anecdotes and numbers. Tone Madison first asked DOC for stats on mail and contraband in a September 18 email. Hardtke’s reply the next day did not answer those questions. We sent back some additional follow-up questions, again asking for contraband stats. No reply. On September 30 Hardtke sent an email to a group of reporters at different outlets, addressing those questions. It is not clear why DOC took so long to provide this information, which ostensibly justifies a policy that has been in place for about nine months. The delay is especially confusing given that the issue of drugs and contraband in state prisons has been front-and-center in Wisconsin news cycles.

Hardtke says that between January 2019 and September 18, 2024, DOC recorded 881 “drug-related contraband incident reports.” In a year-by-year breakdown of these numbers, she writes that 214 of those incidents involved drugs on paper or drugs in the mail. But the way Hardtke’s email phrases this varies slightly from year to year. One year it’s “attempts to smuggle drugs inside personal letters,” another it’s “attempts to smuggle drugs in through the mail or drugs themselves coming in on paper,” and another it’s “attempts to smuggle drugs in through personal or legal mail or drugs contained directly on paper.” And so on. It’s not clear whether these are comparable numbers from year to year.

At no point does DOC specify in total how many of those 214 incidents involved books, much less used books in particular. It makes anecdotal claims about a few specific books here and there. So there still isn’t a good starting point for quantifying how many mailed books allegedly contained drugs. There is a theoretical number between zero and 214, spread out over nearly six years, for a state prison system that currently incarcerates nearly 23,000 people.

Hardtke said in her September 30 email that “three separate shipments allegedly from Wisconsin Books to Prisoners” at Oshkosh Correctional Facility tested positive for drugs, two in February and one in March. Hardtke attached reports from the first two incidents and stated that DOC would release a report from the third once a redacted version was available. (DOC has not released the third report as of this writing.)

By sharing this information, Hardtke may also have inadvertently revealed that DOC violated its own policies dealing with mailed books after an alleged contraband incident.

A stipulation of DOC policy states: “If a publication is not delivered pursuant to sub. (2), the department shall notify the inmate and the sender. The inmate may appeal the decision to the warden within 10 days of the decision.” (Tone Madison has asked the DOC whether or not it reached out to WBTP about this. To date, DOC has not answered this question. It’s not clear whether or not DOC informed the intended recipient or recipients of the book.)

Matthay says that no one at the DOC has ever reached out to inform or question WBTP about the three packages flagged for contraband at Oshkosh in February and March. If DOC staff believed at the time that WBTP actually sent these packages, policy would have required them to notify both WBTP and the intended recipients. This is yet another point where DOC’s messaging about its recent policy changes muddies the waters.

DOC officials have told Wisconsin Books to Prisoners that current restrictions are meant to prevent people from sending contraband in packages that purport to be from WBTP. Hardtke’s emails describe the shipments as “allegedly” coming from WBTP, and does not accuse WBTP of trying to send contraband-riddled packages. But the attached incident reports don’t make a distinction between a package from WBTP and a package from someone pretending to be from WBTP. They describe the packages simply as “boxes of books from Wisconsin Books to Prisoners.”

DOC has not answered questions about whether it then undertook any follow-up investigative steps to determine the packages’ origins, or if so what officials concluded.

To date, these three Oshkosh incidents are the only specific ones DOC has publicly cited of contraband entering prisons in shipments purporting to be from WBTP. But DOC officials have not substantiated one way or another whether they allegedly came from the organization itself or from an alleged impostor. These incidents also came after DOC had reinstated its ban on sending used books in January 2024. It is also not clear whether the packages in question contained used books, new books, or some of each.

The narrative around all this could get even messier, thanks in part to a story published Friday, October 11 in the Wisconsin State Journal, headlined “As Wisconsin prisons crack down on drug smuggling, not even paper is safe.” This stunningly one-sided piece (the only named source is Hardtke) appears to invent a whole new facet of the issue in a passage that mentions “the prevalence of bad actors masquerading as WBTP.” It offers absolutely no information to back up the notion that spoofed WBTP packages are a prevalent problem in and of themselves. Not even the DOC has publicly claimed that; it’s claiming that spoofed mail in general is prevalent. Hardtke has cited the three incidents at Oshkosh detailed above, but hasn’t claimed that fake WBTP packages are a widespread problem at state prisons. Three examples, of the hundreds of contraband incidents DOC reports, do not illustrate a prevalent issue. It doesn’t hold a candle to the prevalence of prison staff smuggling in contraband—which this WSJ article doesn’t mention at all.

Keeping the timeline of communications and policy changes straight is understandably difficult and confusing. Some Wisconsin media outlets have incorrectly reported that DOC reinstated the ban on used-book mailings in August 2024. This is false. DOC informed WBTP of the used-book restrictions in January. On August 16, Sarah Cooper, director of DOC’s Division of Adult Institutions, told WBTP that a “decision was made to no longer allow books in from your organization,” in an email that made no distinction between new and used books. (Several outlets have also cited Cooper’s August 16 email as if it were a message specifically informing WBTP of a ban on used books. This is false. The word “used” does not even appear in the August 16 email.)

Records provided by DOC itself show that Cooper sent this message in response to an ongoing email thread that specifically dealt with the used-book prohibition. In that context, this does not read as Cooper reaffirming an already-existing ban on used books.

Dr. Moira Marquis, an advocate for incarcerated people’s access to books and literary education nationwide, questions the timing of the various changes to DOC’s book policies. Marquis accuses the DOC of trying to institute a total ban on WBTP, and then “flagrantly lying” by claiming that the ban applied only to used books. Marquis wishes that she and other advocates had seized more quickly on the mismatch between DOC’s policy on mailed books and its policy on donated library books: “Why can used books go to prison libraries but not to individuals?” she asks.

Marquis also points out that the DOC changed its library donations policy after the initial outcry over the new mailed-book restrictions. The September 27 policy change also followed closely on the heels of Prison Banned Books Week, an event Marquis founded to highlight prison systems’ outsized role in censorship.

“In another desperate attempt to masquerade as acting in earnest with the best intentions of incarcerated people as their motivation, [the Wisconsin DOC] silently altered the policy to seem consistent with the rhetoric against used books,” Marquis says.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.