It’s the comeback no one expected.

President Trump made a surprising request Sunday evening when he posted on Truth Social, “Rebuild, and open Alcatraz!” — adding that he has directed the DOJ, FBI, Homeland Security and the Bureau of Prisons to “reopen a substantially enlarged and rebuilt” prison on San Francisco’s Alcatraz Island to “house America’s most ruthless and violent Offenders.”

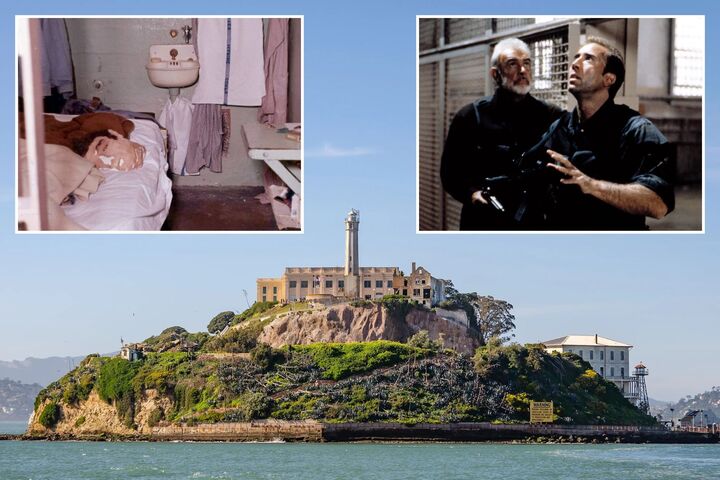

Known in its heyday as one of the scariest prisons in America — surrounded by rough water and loaded with even rougher characters — Alcatraz still looms large despite having shut down in 1963.

That’s in large part because of movies like “The Rock,” “Escape From Alcatraz” and “Birdman of Alcatraz” that have helped burnish its legacy.

But it’s also a major tourist attraction. According to the National Park Service, “Alcatraz Island welcomes approximately 1.2 million visitors a year” and generates around $60 million in annual revenue. (Most of that money goes to financing various projects for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, which the island is part of.)

That said, it’s far from inhabitable.

“The building closed because the infrastructure was almost shot 63 years ago, and it hasn’t cured itself,” John Martini, an Alcatraz historian, told The Post. “There’s no sanitation, no heat, no running water. There is very minimal electricity. You’d have to rebuild it from the ground up … Alcatraz would be a tear down. And you’d have to get heavy machinery out there, rent barges, bring in materials. It would take years to do and right now the goal is so undefined.”

Trump later told reporters his plan was “just an idea I’ve had” as Alcatraz is “a symbol of law and order,” he said. “It’s got quite a history, frankly.”

The island prison known as The Rock began housing inmates in 1934. Built to hold 336 prisoners, there were usually 260 to 275 men behind its imposing walls.

Bill Baker, the last surviving former Alcatraz prisoner, wrote, “It wasn’t much of a life. We walked the yard, talking about robbing banks when we got out; we bet on ball games; and made a little home brew once in a while and got drunk. We were some bad boys … and we were properly punished.”

Situated up on craggy rocks and surrounded by water, the prison offered enhanced security — but the remoteness made it three times costlier to maintain than other federal lockups.

It also made it an incredibly dangerous place to try to escape.

Nobody is definitively known to have successfully broken out, though 36 tried (including two who attempted it twice). Twenty-three were caught and returned, seven got fatally shot, three drowned in the surrounding shark-infested waters, and five were never heard from again. It is unclear whether they died or successfully slipped into anonymity.

The most notorious is a 1962 attempt by Frank Morris and brothers John and Clarence Anglin.

After coming across some old saw blades on the premises, the trio and another inmate, Allen West, crafted crude tools — including a homemade drill made from the motor of a broken vacuum cleaner —to loosen air vents at the back of their cells. According to the FBI’s website, they hid their progress with a suitcase, cardboard and anything else they could find.

Setting up a secret workshop on the roof, accessed by an unguarded utility corridor, they fashioned into life preservers and a six-by-14-foot raft from some 50 raincoats they stole from within the prison, “vulcanizing” the seams by using hot steam pipes — an idea gleaned from a magazine allowed in the cells. They also crafted wooden paddles and even converted a musical instrument into an air pump.

On the night of June 11, they slipped out the vent spaces, shimmied down from the roof unseen and boarded the raft, disappearing into the night.

Guards didn’t initially realize they were missing the next morning because the three had left behind dummy heads — made with plaster and human hair — on their pillows. West later revealed the plans to authorities.

The Anglin family still believes that John and Clarence made it out alive and went on to have new lives as farmers in Brazil.

Either way, their story inspired another famous criminal.

Future mob boss Jimmy “Whitey” Bulger was also serving time for bank robbery at Alcatraz — having been transferred there after repeatedly trying to break out of the United States Penitentiary in Atlanta — when the three fled.

“The morning of the escape,” Bulger would later say, “was one of the happiest moments of my life.”

In fact, he maintained that the trio’s ingenuity inspired him to avoid being captured during his own 16 years on the lam, from 1994-2011.

Another of the prison’s most famous inmates arrived early on. Al Capone, serving time on income tax evasion, landed at Alcatraz in 1939.

According to Jonathan Eig, author of “Get Capone: The Secret Plot that Captured America’s Most Wanted Gangster,” the gangster was sent to Alcatraz — which cost $250,000 (about $5.7 million in today’s economy) — to “show off the new prison and justify its cost.”

Residing in one of the prison’s standard nine-by-five-foot cells, he mopped floors and did laundry. “Al Capone gets no more privileges than the rest, except he does not get beaten or thrown into the dungeon. He has too much political influence for that,” a former inmate once told reporters.

Other celebrity prisoners included Robert “Birdman of Alcatraz” Stroud. A convicted murderer, he earned his nickname in Leavenworth, where he saved the lives of three injured sparrows found in the prison yard. From there he became obsessed with birds, raised them and sold them to other prisoners.

But when he got transferred to Alcatraz in1942, he had to leave behind his beloved pets. Though Burt Lancaster stopped by and interviewed Stroud before playing him in “Birdman of Alcatraz,” Stroud never got to see the movie.

In 1946, a violent but failed escape attempt — set off with guns and riot clubs that a group of cons managed to obtain — led to a two-day-long riot that became known as the Battle of Alcatraz. Before things simmered down, two correction officers and three inmates were killed.

The prison and island are currently in the middle of a $48.6 million multi-year construction project, due to be done in 2027, that will address issues related to weather and aging. But that is a far cry from the level of renovation required to turn Alcatraz into the kind of prison that Trump appears to be envisioning.

Still, a public affairs specialist at the Department of the Interior and the National Parks Service told The Post, “The president’s statement speaks for itself.”

And Martini warns never say never: “With enough funding and political pressure, anything is possible.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.