Aldrich Ames was done selling secrets, but the unravelling of his treachery had just begun.

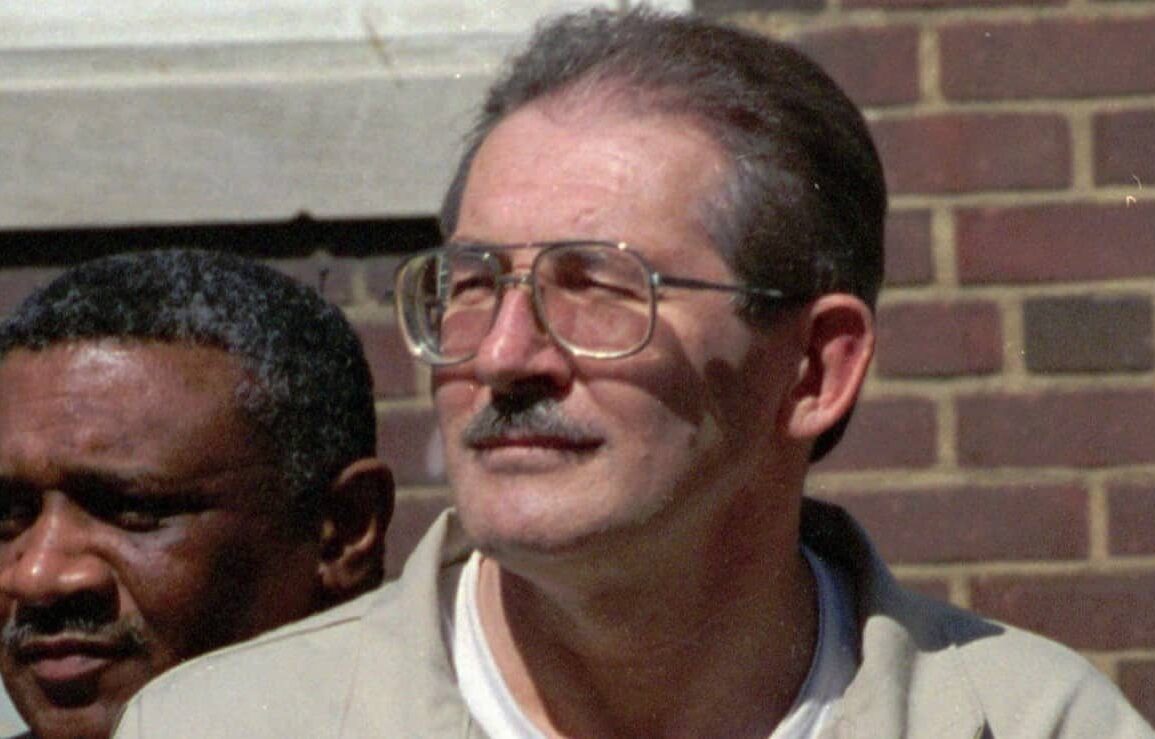

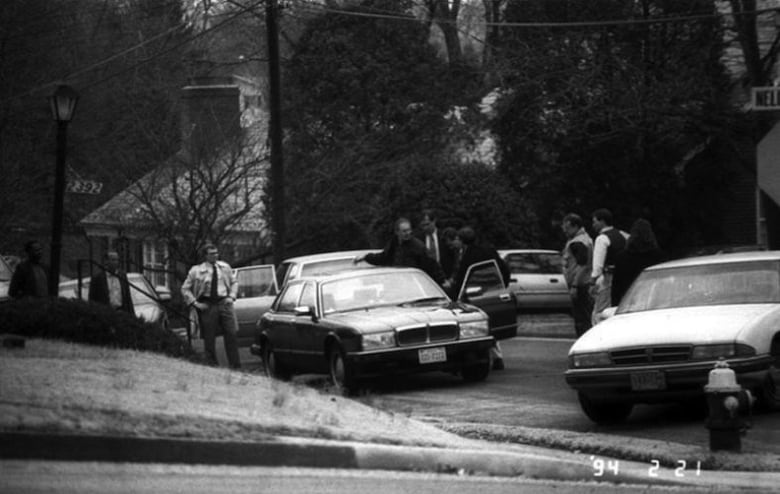

On Feb. 21, 1994, the bespectacled, Jaguar-driving, Central Intelligence Agency lifer, with a cash-purchased home in a Washington suburb, was arrested and charged with espionage.

By that point, the CIA knew it’d been a mistake to have had Ames running the Soviet branch of its counter-intelligence division in the mid-1980s — as Moscow had since paid him more than $2 million US to pass on sensitive information, including the names of people secretly working for U.S. intelligence behind the Iron Curtain.

Two months later, Ames would plead guilty to espionage charges and receive a life sentence for what a U.S. attorney called “the most damaging spy case” in American history.

Thirty years on, Ames remains in custody at age 82. The U.S. Bureau of Prisons website lists his release date as “life.”

In February 1994, Aldrich Ames, a veteran Central Intelligence Agency officer was arrested and charged with spying for the Soviet Union and Russia. Here’s a look at what CBC viewers heard from reporter David Halton, on Prime Time News, after the story broke.

Analysts with knowledge of the U.S. intelligence world say the fallout from these kinds of stinging betrayals can jeopardize national security, damage intelligence-gathering operations, and put lives at risk — all factors that can weigh into determining why some spies, such as Ames, stay locked up indefinitely in U.S. prisons.

“The reason that Ames is going to die in prison is that his betrayal led directly to the deaths of the dozen or so Soviet and Soviet bloc recruited foreign agents that had worked for the United States going back to the 1960s,” said journalist Tim Weiner, co-author of Betrayal: The Story of Aldrich Ames, an American Spy.

Aging spies, frozen lives

Spies condemned to harsh sentences occasionally see a change in their circumstances via spy swaps.

These rare and politically sensitive manoeuvres, involving negotiations at the highest levels of government, have seen caught-and-captured spies freed — such as when the U.S. let Soviet spy Rudolf Abel out just a few years into a 45-year sentence in order to bring captured spy-plane pilot Francis Gary Powers back in 1962.

But Weiner doesn’t see a trade coming for the octogenarian Ames.

“There is no American spy that Moscow ever caught who is anywhere near a fair exchange for that,” said Weiner.

Seven years after Ames’s downfall, another American counter-intelligence agent was caught being paid to give U.S. secrets to Moscow.

In February 2001, Robert Hanssen, a 25-year FBI veteran, was arrested and charged with espionage. He died in prison last year at age 79, while serving a life sentence.

In exchange for a mix of diamonds and cash, Hanssen gave up valuable American secrets to Moscow — including names of people working for the U.S., some of whom Ames had separately disclosed.

Former FBI operative Eric O’Neill helped gather information that helped prove Hanssen’s culpability, including by gaining physical access to the soon-to-be-busted spy’s Palm Pilot.

O’Neill said the veteran FBI agent’s espionage activities involved a mix of old-school tradecraft, as well as more modern methods and technology to access, steal and transmit valuable information — allegedly including U.S. continuity of government plans in the event of war with Russia.

Hanssen would eventually admit to years of spying, and his co-operation with investigators helped spare him the death penalty.

“Hanssen was the bridge [between those eras of espionage],” said O’Neill, who views him as one of the earliest known cyber spies. For Weiner, the Ames and Hanssen betrayals were without “real precedent” in the history of U.S. intelligence — hence the harsh sentences for both.

O’Neill concurs: “There are no two spies that did as much damage to Western intelligence services.”

Eventual freedom for some

There are Americans who were caught passing on U.S. secrets, served their time and later left prison.

Christopher Boyce leaked secrets to the Soviets while working at a defence contractor firm in the mid-1970s. He received a 40-year sentence, later broke out of jail, spent 19 months on the run — robbing banks along the way — and was recaptured. Even so, he was released on parole in 2003.

Jonathan Pollard, a former civilian intelligence analyst for the U.S. Navy, got a life sentence for spying for Israel — a U.S. ally — in the ’80s. However, he was freed in 2015, after extensive lobbying by Israeli officials.

Rosario Ames, the wife of Aldrich Ames, was convicted in the same case involving her husband, but received a lesser sentence. The U.S. Bureau of Prisons says she was released in 1998.

Ana Belén Montes, a U.S. Defence Intelligence Agency analyst who spied for Cuba, was released from prison in January 2023 — more than 21 years after her initial arrest.

At the time of her sentencing, The Washington Post reported that Montes had revealed the identities of “at least four U.S. covert officers working in Cuba,” though “her disclosures did not result in the deaths of any U.S. agents.”

While some may question why spies who sell secrets then receive less-than-life sentences, O’Neill sees minimal distinction between the two outcomes.

“What’s the real difference between 25 years and life?” said O’Neill.

Aloke Chakravarty spent nearly two decades as a prosecutor, working for both the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice along the way — as well as for the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Well-versed in national security-related cases, including those involving espionage, Chakravarty says there are a few key elements that shape how strongly the transgressions are viewed. These include the motivation for the spying, the level of privileged access to information and the extent of the damage done to national security.

In the end, Chakravarty said judges have discretion when handing down a final sentence, though he noted “it’s hard to have mitigating factors in the context of an espionage case.”

The need to know

The Cold War may have ended, but there are still significant tensions between Russia and the U.S. — the nearly two-year-old war in Ukraine being just one current source of discord.

Chakravarty said that context — the relationship between two countries on opposite ends of an espionage episode — tends to factor in to how damaging a particular case is viewed as being, at a given time.

“I think there is a small-p political component for any national security-related crime,” said Chakravarty, who said that stems, in, part from the fact that circumstances can change over time in the relationship between nations.

Yet three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Washington and Moscow still have a need to know what’s going on around the globe.

Weiner points to the run-up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in which the U.S. loudly warned that an attack was looming.

“It did so with absolute clarity,” said Weiner, noting that message collided with skepticism in some corners about Washington’s record on intelligence matters.

The U.S. forecast was proven correct, drawing upon hard information that Weiner said would have come from spies.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.