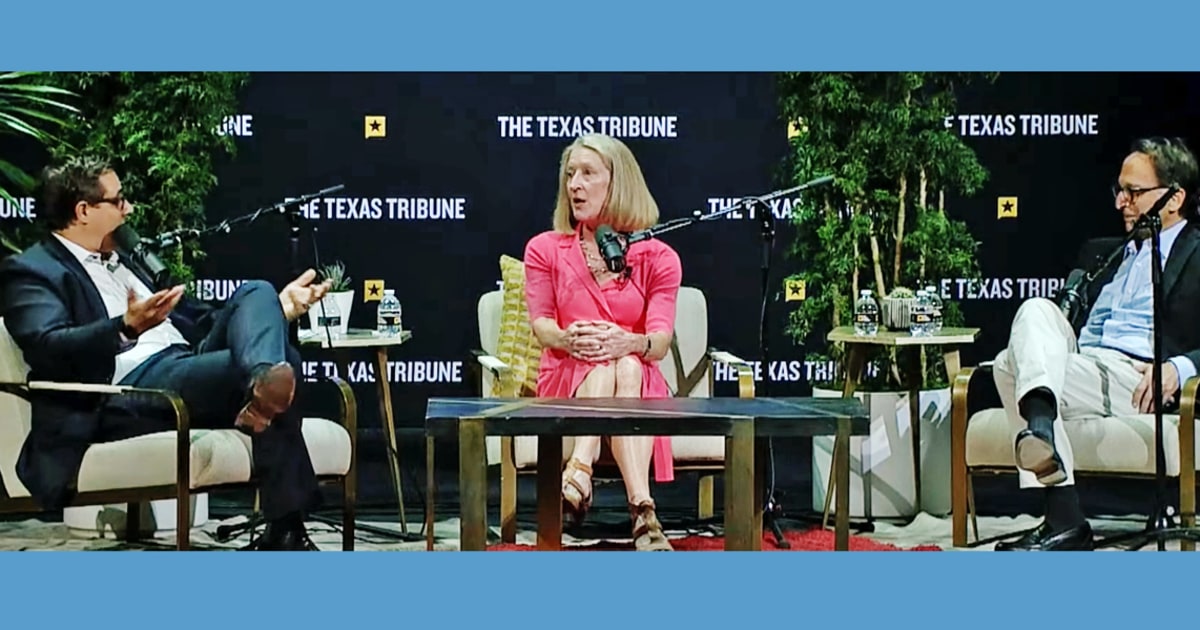

We just got back from the first stop on our fall 2023 WITHpod tour. We’re thrilled to share a recording of our live event at the Texas Tribune Festival with Andrew Weissmann and Mary McCord, co-hosts of the MSNBC podcast, “Prosecuting Donald Trump.” Weissmann and McCord, who are both former federal prosecutors, joined in Austin, TX to discuss former president and criminal defendant Trump’s continually growing legal issues as the country prepares for the presidential election in 2024. They also talk about the key point that up until recently, everything that’s ever happened to Trump in the past with regards to the law has happened in the regime of civil law, which charges in their view will be the clearest, whether they think he will be convicted before Election Day in 2024 and so much more.

Note: This is a rough transcript — please excuse any typos.

Chris Hayes: Hello and welcome to “Why Is This Happening?” with me, your host, Chris Hayes. Well, WITHpod listeners, if you’ve been following along with our latest “Why Is This Happening?” updates, you know that we are now on tour officially. In fact, just got back from the first stop over the weekend, which was a blast.

Don’t forget you can still join us for some of our other events this fall. You can get your tickets at msnbc.com/withpodtour. Our first show on this tour was great. We had an amazing time, and we are so glad to share the recording of a live event with you. Hope you enjoy.

Doni Holloway: Hey, Austin, Texas. Hey. Good afternoon, everybody, and welcome to our live recording of “Why Is This Happening?”, the Chris Hayes podcast. We are so thrilled that you’re joining us here.

I’m Doni Holloway, producer of “Why Is This Happening?”. And I’ve got to say, we’ve got a great show ahead for you.

Just one reminder before we get started, don’t forget to share some of your favorite moments from today’s conversation using the #WITHpod as well as #TribFest23. That is the hashtag.

We are so excited for today’s program. We’ve got a great show ahead for you. And without further ado, I am so happy, and please join me in welcoming our host, Chris Hayes.

Chris Hayes: Hey, everybody. How are we doing? It’s great to be here in Austin, Texas. Great to be here at the Tribune Fest. Thank you all for coming. We do this podcast, “Why Is This Happening?” comes out every week on Tuesdays.

And I’m going to start today’s show with a thought experiment, which is intended as a kind of provocation. So let’s imagine a construction project, maybe a building being rebuilt. And on that construction project, there’s copper laying around.

And someone who is desperate, poor maybe in the throes of substance use disorder comes upon that construction site and steals $500 in copper wire. And there’s a security camera and that person is caught and they are charged. That person has committed, I think we would all agree, and the law certainly agrees, that person who’s stolen $500 in copper wire. By the way this happens a lot. Copper’s pretty expensive. That person who’s stolen $500 in copper wire is now facing criminal charges.

They are squarely on the wrong side of the criminal law regime. They have committed a crime or at least until that’s been proven guilty in an alleged crime.

Now when this construction project ends and it’s all finished, the developer of the project owes the contractor $50,000. And the developer of the project just says, “I’m not paying you.” What are you going to do about it? That’s also something that happens.

That contractor has had essentially $50,000 stolen from them. I think we would all agree, like at an intuitive moral level, right? They have had $50,000.

But the developer has not committed a crime. If you try to go to the police station down the block from this construction site to say, this guy stole $50,000 from me. They’re going to tell you, buddy, get a lawyer. That’s not our job. That’s going to be a civil suit.

If the law is going to deal with the $50,000 that this developer has not paid the contractor, that is going to happen through civil litigation. They’re going to have to get a lawyer and they’re going to have to sue them. And I think about this, the reason I’m talking about this is to think about the sort of status of the person who steals $500 worth of copper wire versus the developer who essentially steals $50,000 from the contractor and which side of the law they fall on, and how the law deals with each of them.

So the person that steals $500 in copper wire is going to be charged with a crime and they’re in the regime of criminal law. The developer who has stiffed the contractor for $50,000 is not going to be charged with a crime, definitely not going to be arrested, certainly not going to go to jail and not be bailed out. They’re not going to have to experience what that looks like. They’re going to face civil litigation.

Now, the lawyers in the room are saying, well yeah, but there’s differences between criminal and civil law. But I want to just make this provocation to start tonight before I introduce my guests and talk about the most important and consequential criminal prosecutions that have probably ever happened in the history of the republic.

From a sociological standpoint, if you just came from Mars, right, if you were sort of an alien anthropologist observing the way that the law works. It wouldn’t be the craziest conclusion to say that what criminal law does is it is the regime of law used for people who are poor and without power, and civil law is the regime for people who have power and money.

But that’s actually really whatever the sort of legal theories about what distinguishes someone from a criminal violation versus a civil one, at a sociological level, if you go to an overnight booking at a local criminal court here in Austin or in New York where I live or anywhere, sociologically you’re going to see people getting run through that system that are pretty consistent demographically.

And if you work for a big law firm doing civil litigation, you’re going to see a very opposite demographic of the folks that are involved in that sort of thing. And so, the provocation from this thought experiment is to think about what it means of the way that civil law functions in our society and criminal laws on functions.

And the person in some ways who best represents, as a human being, in lived experience, that exact provocation I’m making is the former president of the United States now criminal defendant, Donald Trump.

Donald Trump stole a lot of stuff from a lot of people. I mean, there are piano tuners, it’s true, from Atlantic City who still haven’t gotten their $15,000. In fact, he was notorious around New York for stiffing contractors. There’s a fairly plausible facial case to make that he committed tax fraud for years, as revealed in “The New York Times” story. And he has also been involved in more litigation probably than almost any other person in the country, hundreds and hundreds of lawsuits.

But he’s rich and he’s powerful, and everything that’s ever happened to him with regards to the law has happened in the regime of civil law. Criminal law are for Harlem teenagers who get accused of a brutal crime in Central Park and sent away. That’s what criminal law is.

And what’s so fascinating about the path that we have before us with the former president now facing 91 counts of felony indictments in four different jurisdictions is a real, almost existential test of what the law is. What is the law for? What is criminal law for? What does it mean to be a nation of laws or a society under the rule of law?

A system that exists largely in the context of people that, again, at a sociological level, poor, don’t have a lot of power, that system is going to attempt to secure a conviction against the most powerful person it’s ever tried to secure a conviction against. Can it do it? And I can’t think of a better group of people, two people to have that conversation with than my next guests and I want to ask you to give a warm round of applause and welcome to the hosts of the “Prosecuting Donald Trump” podcast, Andrew Weissmann and Mary McCord.

For conversational efficiency purposes, I did not give your very long and august bios. You’re both very fancy people with long CVs and many years working in the government and as you worked as prosecutors. So I want to just start with this, like your response to this provocation.

Like I know. Again, I know I’m not a lawyer, but through the magic of marital osmosis, I’ve learned a thing or two, and I understand theoretically, but what do you think about when you think about the fact that here’s this guy who really has stolen money from people in an intuitive moral sense, he’s never been in handcuffs, right, and what it says about how the law operates and what criminal law is for?

Mary McCord: So I think, you know, we definitely have examples of rich people who have had to face criminal penalties.

Chris Hayes: Totally.

Mary McCord: Like Bernie Madoff, Jeffrey Epstein, Jeffrey Skilling, Michael Milken.

Chris Hayes: Although, the Supreme Court kind of walked that one back, pretty crucially.

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah, he did 12 years.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: As this audience may know.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: Michael Milken, ironically, prosecuted by Rudy Giuliani, pardoned by Donald Trump, right? So it’s not as though people who are extraordinary wealthy always escape criminal prosecution, but they’re definitely, the system operates differently and I’ve spent most of my career prosecuting. And I think it’s for a lot of reasons and it’s oftentimes not because of the way the prosecutors would view a case. It’s because of the resources that the people who are wealthy have, right?

So they, oftentimes, if they’re being investigated, because it’s usually not for a street crime like stealing copper tubing –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: — or copper wire, it’s oftentimes for some sort of white collar offense: securities, fraud, insider trading. Of course in the case of Epstein, it was sex trafficking of minors. That’s a little bit different than your normal, right?

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Mary McCord: But a lot of times these investigations are known before there are criminal charges. So people with wealth, they’re able to hire very high-powered, well-connected attorneys who put armies of associates on the case. And the government oftentimes, there are exceptions to this, Enron and others, exceptions which you can talk about, government is usually pretty leanly staffed.

And so, they’re outnumbered already from the beginning, oftentimes can work their magic to have the case never brought to begin with or have some resolution. And so, most of your criminal defendants, like your hypothetical, you know, person who stole the copper wire, you know, they are indigent. They can’t afford to hire an attorney. They have an attorney appointed for them, a public defender.

Some public defenders, like in Washington, D.C. where I practiced law, are excellent, the federal public defender and the local public defender. New York City also has excellent, but other parts of the countries, the public defenders have 400, 500 cases a person. The best they can kind of do is just get in there and do their best at trial, right?

So the system is stacked really from the get-go. So, there is something of a two-tiered system here, but with respect to Donald Trump, he of course has never been on the other side of the V in a criminal case, and I think that’s partly why you see him lashing out. He has figured he could buy his way out of every wrong that he’s ever committed through attorneys like the now disbarred Roy Cohn and through bankruptcy multiple times, right? And now I think his back is against the wall. He doesn’t act like that, but it is, and he can’t buy his way out of it.

Andrew Weissmann: So I love your hypothetical because it seems like it’s a perfect anathema of “Why Is This Happening?” and “Prosecuting Donald Trump.”

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: So, it’s like two podcasts merged. And I think it raises interesting but, I think, very different issues. I mean, one is a sort of big picture issue of what do we criminalize and why do we criminalize something. Before when we were listening to this, Mary and I were saying in the 19th century in England that you would have had a different result because there was debtors prison and so you can have just different criminal laws that would work differently.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: I think that, you know, if the other sort of like smaller picture issue is who is most affected by criminal and civil laws, there’s no question the civil system is for wealthier people both because of the cost of entry into it and meaning the bringing of a lawsuit and the lawyers that you need. And then you’re not going to usually sue somebody who doesn’t have any money. It’s like what’s the point?

Chris Hayes: Right. That’s a good point.

Andrew Weissmann: So, there’s just going to be about wealthier people in the civil system. On the criminal system, for the reasons Mary said, there’s no question there’s a complete racial disparity, but I’m not sure that’s because of what is criminalized as opposed to how it’s actually implemented.

I spent, I think, almost my entire career after my first year as a prosecutor prosecuting wealthy white people, whether it was in organized crime, the Enron Task Force or the fraud section where we did corporate cases, that that is really unusual.

We’re talking about the federal system and it’s even unusual within the federal system. But remember, the federal system is like a tiny little pimple on an elephant –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: — you know, in terms of, you know, who’s getting prosecuted. So usually, as Mary knows from prosecuting in D.C., that is just very much, you know, black and brown communities being disproportionately prosecuted.

My third point is just relating it to Donald Trump. It’s sort of like this is all really interesting. These are crimes that you don’t have to really get into sort of the niceties of the law. It’s like, let’s see, overthrowing a presidential election. As Mary and I know having been in the intelligence community, it’s not just mishandling documents. I mean, this is disseminating national security documents to a third party.

I mean, very often people say, oh, you know, if I did that, I’d have been locked up, and sometimes I’m thinking, well, that’s probably not exactly right. This is one word.

Chris Hayes: Yes.

Andrew Weissmann: Mary and I, if we did anything even close to that, handcuffs, off we go. So, it’s just so egregious in terms of applying it to Donald Trump and what he’s alleged to have done.

Chris Hayes: Yeah. I mean, I, to be clear, agree completely. And I think that the way that these two systems function is partly things that happen before you even get to the law, right?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes.

Chris Hayes: Like the structure of American society who has wealth, who has power, before you get to the law.

But what it brings up to me, which is this really kind of important and high-stakes question before the country now, which is the nature of the law because Donald Trump has a theory of the law and his theory of the law is rule by power.

Actually, it’s a theory of the law that I’ve only encountered in leftist undergraduate circles, you know, which is basically like that bourgeois liberalism is a joke and that the laws that you’re so into are actually just the cloakings of power and power is what determines the law.

And Donald Trump believes that both as a descriptive matter, like he thinks that describes how the law functions, and also as a norm of matter. He thinks that’s the way the law should function. But the law is just rule by force, right? Might makes right, essentially. I will prosecute my political enemies.

And then on the other side of that, you have the Merrick Garland facts and the law. Like this very —

Andrew Weissmann: You say that with all due respect.

Chris Hayes: Yes, with all due respect to the Attorney General of the United States.

And you know, I would love to hear you guys talk about this question. Because to me, I obviously think that Donald Trump theory is wrong. But I also find myself shrinking a little bit at this kind of facts and the law, balls and strikes, the thing that prosecutors are doing is no different than like measuring a fish you might have caught, like you pull it out of the water and you’re like, well, it’s 11 inches, that’s a crime.

Like there’s a lot of judgment. There’s a lot of discretion. There’s a lot of sociological institutions that are functioning together to produce a prosecution. That, to me, it’s not that Donald Trump’s critique is right, it’s just that like what we’re doing here and particularly in the case of this guy who like everyone who’s bringing the charges knows what they’re doing, there is something different at some level about what’s happening here.

Mary McCord: And I think that’s partly because this is so unprecedented, right? So the rule of law, just as a general principle, is that the governed and the governing sort of agree to be bound by and accountable to a set of laws that are publicly promulgated, that are enforced evenly and fairly, and that when there are disputes, they’ll be adjudicated by independent and neutral arbiters, right?

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: So those are like just the principles of the law.

Chris Hayes: That’s good. Yeah, that’s a good —

Mary McCord: Right. So to your point, Donald Trump is, yeah, except me, except for me.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: And outside of that, that applies to everybody else.

Chris Hayes: Or my friends, yeah, correct.

Mary McCord: Or my friends, right. And so, anybody powerful enough, anyone who’s able to pull the levers of power, whether you’re outside of the government or inside of the government, well, you get accepted from that sort of rule of law.

So I think what you see from people like Merrick Garland and all of my former colleagues in the Department of Justice is they are just trying to strictly adhere to those principles. And independence is one of the critical ones because the Department of Justice is part of the executive branch.

The president, when you are president, not when you are not president, is the leader of the executive branch. You and I talked a little bit about this earlier, there’s nothing in the Constitution that says a president could not direct his attorney general to investigate cases he wants him to direct.

And, in fact, presidents do make sort of policy choices about what things are going to be priorities for the administration.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Mary McCord: And then they have a political appointee as the attorney general who implements policy.

Chris Hayes: Edmund Mason pornography.

Mary McCord: Right.

Chris Hayes: I mean, that was a big thing. The Department of Justice is going to go to court.

Mary McCord: And think about during the Trump administration, Jeff Sessions was the first attorney general. There was like a zero tolerance at the border policy.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Mary McCord: You know, all these things, and that’s implemented in ways that hadn’t been implemented before.

So there is leeway there, right, for there to be policy priorities under any administration, and an attorney general will typically, you know, try to carry out some of those policy priorities. That’s very different from, you know, making individual decisions about prosecuting one’s political enemies.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Mary McCord: And maybe even though that’s not in the Constitution, the Constitution has other things that protect defendants. Due process. You have a right to due process of law substantively and procedurally and all of the other protections, constitutional protections that come along with it.

So a lot of the things that have developed over time and I think this is where Donald Trump just like completely, you know, turned the table over on this. A lot of what has developed over centuries, but really I would say modern history because if you go back too far, you start finding some pretty squirrely things, right?

Chris Hayes: You really do. It’s really post-Watergate. Let’s be clear, it’s really post-Watergate.

Andrew Weissmann: That’s right, post-Watergate. These are norms that career Department of Justice and I was always career even when I was the assistant attorney general for national security. I was in an acting capacity, so always career.

Career Department of Justice attorneys, they just respect this idea of independence.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Mary McCord: And we will not be, as Merrick Garland said just this week, you know, they’re not there to be the president’s lawyer. They’re not there to be Congress’ prosecutor.

But Donald Trump really tries to turn that on its head, and I think that in doing so, I’ll be curious, Andrew, what you think, I think he exposes what probably a lot of people with wealth have always thought and always believed and sometimes been successful at but never said it.

Chris Hayes: Slash, I think that, and I’ll let you respond, Andrew, but I think it’s two things. I think it’s people with wealth who have experienced the law that way. I think people without wealth who do feel like the system is rigged or whatever, right?

Mary McCord: Right. Yes.

Chris Hayes: That, like, do have a very cynical view –

Mary McCord: Yes.

Chris Hayes: — that these people are all corrupt, that like, give me a break. And I think that’s part of the appeal of that that’s his message.

Andrew Weissmann: So, I think that what Donald Trump has done is quickly learned where there are fissures in the structure that’s created and where he can exert power. So, I was on the special counsel Mueller investigation. There it was about he could do essentially a Saturday Night Massacre. It’s like, you know what? I can fire these people. He can issue pardons. He can dangle pardons. He was like figuring out what can he do.

Now since he is not the president, he can sit there and say, okay, you know what? I can’t fire, but maybe I can defund them and cause a stop that way because I do not have the power, but maybe I can get my friends in Congress to defund them and figure out how to use them as a lever of power.

I can use fear. One of the more chilling aspects of the Mitt Romney reports coming out of people saying I decided not to follow my oath of office as a senator because I was concerned about my family and friends, which, you know, as former prosecutors and seeing witnesses and judges and jurors, you know, almost every day of the week follow their oaths of office in spite of that, it was incredibly disheartening to see that report.

But he uses fear and fear and actual real violence to have people say, you know what, maybe we shouldn’t stand up here. So, he has various levers to use that, of course, if you’re somebody who’s, you know, really disenfranchised, you’re going to be thinking this is like outrageous.

It’s outrageous no matter what, but obviously for people who are in the criminal justice system thinking, I don’t have anything close to this, let alone the resources to even hire, you know, X, Y and Z, you know, defense lawyers. I would say it’s more than a two-tier system, but that’s sort of a given and just to relate it to Enron since we’re out here in Texas. I mean, there Jeff Skilling had more partners representing him than we had on the Enron Task Force, and that’s one defendant.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: And there were a slew of defendants.

Mary McCord: That was a big task force for a prosecution.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Mary McCord: I mean, that was big.

Andrew Weissmann: And the message there is not that defendants shouldn’t have good representation, it’s that it’s so disproportionate.

Chris Hayes: Yes.

Andrew Weissmann: And it’s also disproportionate when the judges are of the same background demographically as the defendants and things get said like when somebody was sentencing the head of investment banking at Merrill Lynch, the judge in Houston said, you know, unlike other people who appear in front of me, you will not suffer the opprobrium. That most people don’t suffer from this opprobrium.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: You will because you’re going from head of investment banking to being convicted.

Chris Hayes: Oh, my god. The judge said that?

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah. So, you have this extra review and scrutiny that’s like a thumb on the scale if you are a certain type of person.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: Again, it’s not that there shouldn’t be that. It’s just should be applying to everyone.

Chris Hayes: You brought this up. Let’s talk about the two cases brought by the special counsel, because you talked about this. You know, the norms of the independence of the Justice Department really are in their current incarnation of post-Watergate, right?

The Saturday Night Massacre catalyzes and sort of makes active and this is both in, I think, some in statute and some in norms, this idea of DOJ independence. Because, intuitively, I think we would all agree, right? It just cannot be the case that the federal government’s Department of Justice.

If the president wants, if he has a statutory authority on some new traffic initiative, like that’s his prerogative, you know, right? But it just can’t be the case of like, I want you to go investigate these 10 people. We all kind of understand that. But there is a kind of like Chekhov’s gun about the Department of Justice to me that sort of hangs over all of this, which is like when Merrick Garland says we’re not the president’s lawyer, we’re not Congress’. We’re there for the people. It’s like, well, who do you answer to, right? Like who does the Merrick Garland answer to?

Like at one level he answers to Joe Biden as the president who appointed him, but at another level, he can’t really on some of these questions, particularly vis-à-vis these two independent prosecutors, one is going to be prosecuting the president’s son, one is going to be prosecuting the president’s likely opponent.

And I guess my question is like how should we think about the special prosecutor’s office and what that really means even at a ground level, Mary? Like how it’s operating, what it means to say they’re independent?

Mary McCord: Yeah. So, it’s interesting because I think there’s a lot of confusion about the idea of special counsel –

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Mary McCord: — because under the special counsel regulations, they really are treated very much like a U.S. attorney, right? So we have 93 U.S. attorneys out there that represent the various. They’re broken down by, essentially, judicial district across the country.

I spent 20 years in one, and I would tell you I spent 20 years trying to avoid ever going down the street to main justice because we felt like, for D.C., we make our decisions.

Chris Hayes: Leave us alone.

Mary McCord: Forget the White House. We didn’t even want to deal with the attorney general, right?

Chris Hayes: Totally.

Mary McCord: Like we have one political opponent.

Chris Hayes: How dare you?

Mary McCord: Exactly, the U.S. attorney. We’re responsible for deciding –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: — what priorities are in the District of Columbia based on what the threats are, both violent and nonviolent, white collar and what have you, national security, although that’s a whole different story because you have to get involved with the main justice in national security cases.

And so, I think a lot of people think the Special Counsel has some other degree of independence.

Chris Hayes: Right, it’s just like a U.S. attorney. That’s actually super useful.

Mary McCord: Yeah.

Chris Hayes: They’re just the U.S. Attorney without a physical location, yeah.

Mary McCord: Right, they don’t have their own –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: — U.S. Attorney’s office because U.S. attorneys and special counsel have to do these things called urgent reports. When you’re going to take any step in a significant or sensitive or, you know, high profile investigation, that means start to take covert steps in your investigation, bring charges, make a sentencing recommendation, you have to send a report up to the attorney general. So does the special counsel.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: Now, the special counsel, the decisions and the attorney general’s ability to overrule those decisions are a little bit different because I suppose the attorney general for any reason could just overrule a U.S. attorney whereas the special counsel regulations say that if the attorney general thinks that a decision of the special counsel is so unwarranted, right, or unjustified, then he could overturn it and then he knows he’ll ultimately have to report that to Congress.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: So, that’s where it’s a little bit different, but it still is not total independence. So, when David Weiss brought charges against Hunter Biden, those went up to Merrick Garland, just like when Jack Smith brought charges against Donald Trump –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: — those went up to Merrick Garland.

Andrew Weissmann: So, I’d add a couple things. Just when you want to bring a tax case, since that’s in the news, you have to get tax division authority. So, even if you’re a special counsel, you have to do that. When we brought tax charges against Paul Manafort and I remember thinking, this may help us because it’s like it’s not just us. This is actually the whole department.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: If we want to bring Foreign Agent Registration Act cases, we had to get the National Security Division approval.

So, it really is very embedded within DOJ. I think the main thing about special counsels, though, is that these are internal DOJ guidelines. And to your point about just sort of how ethereal and wispy this is, the reason that the special counsel internal DOJ regulations are constitutional because we litigated it, I think, three times in the Mueller case, is because they’re so wispy and I remember that there’s —

Chris Hayes: Right, if they were stronger than that, they might not pass constitutional muster.

Andrew Weissmann: Yes.

Mary McCord: It failed in the past, the independent counsel.

Chris Hayes: Right, yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: So, the wording was that Special Counsel Mueller was constitutional because he is a “subordinate officer,” which we kept on teasing him about. So, you’re just a subordinate officer and he loved that. But that was why it was constitutional, meaning that any day of the week, the attorney general can go these are my regulations, and now they’re not. I mean, he can do whatever he wants.

Chris Hayes: Again, which is on the other side of this accountability question, sort of important, right? I mean, at some level, someone has to answer to someone who ultimately derives their power from the American people who elected them.

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah, but isn’t the answer to that even though prosecutors have enormous discretion about what deals they make, who they’re going to charge, the Hunter Biden case is a perfect example. There are all sorts of ways that could have been charged, could not be charged, how it’s going to proceed.

But at the end of the day, I think the check, if you say you want to have an independent DOJ from the president, and it’s like who do they answer to? Well, in this country, you can get charged, but you need to have a grand jury. Now, I know that’s just probable cause and it’s a low threshold, but that’s what we all have. But at the end of the day, you have to prove guilt to us.

Chris Hayes: You guys.

Andrew Weissmann: So, I think that is the ultimate check and I know that’s a little harsh when the person has to live through that.

Chris Hayes: See, that’s the question because the question I have about this, and I’ve run this. Again, I’ve thought about this a lot, like the Durham prosecutions are great, right, where people know there’s this sort of anti-special counsel, special counsel. Do people know about John Durham? Like Trump? Great. You’re right.

So, they made like a special counsel to investigate the special counsel or like —

Mary McCord: Investigate the investigators.

Andrew Weissmann: I’ve heard of that, Chris.

Chris Hayes: Yeah, you’ve heard of that. Like undo their work and then like he clearly went on this insane goose chase. It went longer than the Mueller office. It cost more money. Did he lose three cases or two?

Mary McCord: (Inaudible) —

Andrew Weissmann: He had one guilty plea and he lost the two trials, which means, just to be clear, 24 jurors found that there was not proof beyond reasonable doubt.

Chris Hayes: I mean, this is wild. This never happens.

Andrew Weissmann: Never.

Chris Hayes: Never. Like DOJ’s win rate is like 98 percent or something to lose two trials. And so, in that case, the ultimate check, that’s a great example of the ultimate check, right?

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: It can’t just be politics because we actually sort of almost ran the experiment. It’s clear that’s what Durham was. It’s clear that that was his mission, was to sort of settle scores politically and 24 different jurors were like, nah, dude.

But then here’s my question for you, and I’ve been thinking about this with Hunter Biden. I want an honest answer. If you took anyone in this room, anyone on stage and you had enough time and resources, could you find a prosecutable crime to prosecute them for?

Mary McCord: No. You guys are all sus (ph).

Chris Hayes: Specifically that dude in the fourth row.

Andrew Weissmann: Well, Chris, I don’t know you well enough, but I can say with Mary, the answer is no way.

Chris Hayes: I think I would agree. I think that’s the case. I mean, right, so A, you don’t know the answer.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: But I guess my question is like there is a little —

Mary McCord: Dig Dug in dugging it, right (ph)?

Chris Hayes: Because Hunter Biden thing feels a little like that. Now, obviously this is man we know has committed crimes because, by his own admission, he has had a long history with substance addiction that has involved illegal substances. So, there’s no question that Hunter Biden’s committed crimes. We know that. He’s sort of a special case.

But the broader question, which is like this kind of if you just chose someone, can you come up with not something that secures conviction, but a colorable —

Mary McCord: Jaywalking, you know?

Andrew Weissmann: But that to me, though is really the issue that I think is legitimately raised in terms of asking yourself with respect to Donald Trump or, frankly, any defendant is are you treating that person comparably. And if you’re not —

Chris Hayes: That’s it.

Andrew Weissmann: If there’s some difference, is there a legitimate reason for that, because sometimes there is. And I just think with, just take the big picture, which is Donald Trump, because Hunter Biden, it’s just such a non-issue in terms of big picture.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: Donald Trump, okay, so let’s do the test of is he being treated comparably to anyone else? Would he, if his name were, you know, John Smith, would he be charged? In the Mar-A-Lago documents case, Mary and I can tell you 100 percent –

Chris Hayes: One hundred percent.

Andrew Weissmann: — and that’s not an opinion. There are –

Chris Hayes: Yes.

Andrew Weissmann: — documented DOJ cases of people who have done far less —

Chris Hayes: There was like an Air Force lieutenant colonel in Florida.

Andrew Weissmann: Exactly. Junior people go to jail for this. They get prosecuted, too. Again, you want to look at that, and I think that’s a fair question to ask. And I think with respect to the January 6th cases, you really don’t even have to go very far. You have to go to the hundreds of people in DOJ.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: And one of the things that’s just so unique about the courthouse that he’s in is the judges there have been inundated with those cases. So, the reason you’re hearing judges who have said, essentially, where is the white collar component of this case, we’re seeing the foot soldiers, what are called the blue collar crime, is they every day have been seeing this.

So, when you’re thinking about comparability —

Chris Hayes: Great point.

Andrew Weissmann: — there you’re saying, wait a second. The people who are more culpable are not in the door.

Chris Hayes: Yeah, we’ve run hundreds of people through this building.

Yeah. I mean, let’s talk about the actual cases here, because I like this theoretical stuff. But, you know, it’s funny, like for me like during an election season, it’s like everyone, as long as humans, you know, first evolved, like we want to know the future and we can’t. That is our lot. And you could read the stars, you could do goat entrails, you could do tea leaves, you can go to crystal balls or you can like aggregate polls. Like it’s all the same stuff because it’s like we want to know the future and yet we can’t. So, will ask me during —

Andrew Weissmann: What’s going to happen?

Chris Hayes: Right. People will ask me during election year, like who’s going to win. I’m like, I can’t tell you. But what I want to be is like, is he going to be convicted? Like what is your best assessment? Let’s talk about the Jan 6 case. Let’s talk about Chutkan and March, which seem, to me, on the way forward. What’s your best assessment of what the next six months look like?

Mary McCord: Yeah. So, there’s a lot of variables there. I think that definitely Judge Chutkan by choosing that date, which was, you know, faster than Donald Trump wanted. He wanted 2026, but it was slower than —

Chris Hayes: That was so funny. That was a very funny bid.

Mary McCord: That was so fun, I know. It was. Yeah, it was.

Chris Hayes: Legitimately funny.

Mary McCord: So, it’s like after I’m dead, you can prosecute me, basically.

Chris Hayes: Yeah. Does never work?

Mary McCord: Yeah, never. It’s never is what he wanted, because if he wins or if any Republican wins that becomes never. And I think, you know, she set out a scheduling order with interim dates for everything. People always focus on the trial date, but there’s dates that motions have to be filed, there’s dates that witness lists have to be presented, there’s dates that discovery has to be finished, all these kind of things. It’s all set out very carefully.

But that could all get derailed if there are decisions that have to get made on motions that are appealable. Now, normally in a criminal case, there are very few things that a defendant can appeal until the end of the trial.

Chris Hayes: It’s called interlocutory appeals or ones that you can do before an actual verdict.

Mary McCord: That’s right. And those are very limited, and they’re really limited to things that if you don’t get that chance to appeal now, like it’s irreparable. You can’t undo it.

Chris Hayes: Yeah. Right.

Mary McCord: Now, you might say, well, isn’t that the case for all criminal defendants? Let’s assume you went through a trial. You were convicted. Let’s assume you were detained pretrial, which, of course, he is not and then you win your appeal. It’s pretty irreparable, right?

Chris Hayes: Yeah, can I get the year I did in Rikers back? Yeah.

Mary McCord: Exactly, right? But here it really means things that you have a constitutional right to that you would then lose. So, let’s talk about things like immunity. We know that Mr. Trump’s attorney has said, I will be filing a motion to dismiss this case on the grounds of presidential immunity. That’s executive immunity basically saying you’re prosecuting me for things that were within my authority as president to do and I can’t be prosecuted for that.

Assuming that he files that, he’s been saying he’s filing it for a few weeks and he still hasn’t filed it, but assuming he files that, and assuming that is denied by Judge Chutkan, that’s one of those things that you can’t put back in the bottle. Because if you’re immune from a suit, it means you don’t even have to stand trial for it.

Chris Hayes: Correct.

Mary McCord: You’re immune. Kind of like double jeopardy, right? If you’ve been put in jeopardy once through a trial, you can’t be made to do it again.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: So, that’s something that is almost certainly appealable, right? So, that throws the schedule off, and she can’t really go forward, at least with trial because then that would violate this idea of immunity. So, that means the Court of Appeals would have to, you know, make an expedited schedule to brief it. Let’s assume that the Court of Appeals denies, you know, agrees with Judge Chutkan and does not grant Mr. Trump immunity. Guess where he goes next? The Supreme Court.

Now, they don’t have to take a case and maybe they wouldn’t. But I’m thinking that when we’re talking about, you know, a year of an election and a candidate for election, the former President of the United States, it’s something they’ll think long and hard about.

Chris Hayes: I mean, I guess my feeling on this, again, this is not a legal determination, but it’s a political one, is that we are not going to get through the first ever prosecution of an ex-president without the Supreme Court –

Mary McCord: Supreme Court.

Chris Hayes: — weighing in some way, yeah.

And my fear, Andrew, is that the way they weigh in is the way that they weighed in on redistricting in Alabama in an election year, in the Milligan case, in which a suit was brought saying these maps violate the Voting Rights Act. And they said, yeah, we’ll argue it, but suck it up and just deal with them for now. We’ll get to it later. The map stayed in place in election year. A Republican was elected in one of the districts that probably would have been redistricted for a Democrat. The case went up. They had merits briefs and arguments, and they found, for the plaintiffs, that the maps were wrong. But it’s like, well, too bad, too late.

My fear is that they try to get something on immunity to interlocutory repeal and the worst case scenario is like a shadow docket unsigned something that’s just like, yes, Donald Trump gets to escape until afterwards. We’re putting this on pause.

Andrew Weissmann: So, I’m usually not the optimist.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: And there’s no question that Mary is flagging, I think, the one sort of real unknown that could throw this off. As horrendous as the last term of the Supreme Court was on so many levels, I don’t see this happening, and I think Judge Chutkan knows exactly what she’s doing.

As I’ve said, I think the March 4th date, I don’t know what was in her head, but it is notable to me that that was a very long time, until was it 1930 or so, was the inauguration date. It was the date that our Constitution went into effect. It just seems impossible to me to think that she didn’t know that.

Chris Hayes: That date is also a full English sentence, March 4.

Andrew Weissmann: Yes. Thank you so much, Chris. Okay.

Chris Hayes: That’s a fun bit of trivia, you guys. That’s free. Keep that.

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah, I like that.

Chris Hayes: Use it next time.

Andrew Weissmann: Okay. So, I just think that if I had to bet, I would say it’s going to go forward. I think she knew what she was doing by setting the date before the Florida Judge Cannon date that she was not going to be held hostage to whatever shenanigans go on there. And so, I just think that’s going to happen.

And I also think the federal prosecutors, I think, have a very good sense of keeping the case as short as possible –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: — and streamlined. That’s usually a very good thing for prosecutors.

Chris Hayes: If they are able to get something immunity and a locatory (ph) appeal, and I agree, I think it’s clear that Chutkan is going to not rule for that and I would suspect that the D.C. Circuit would also rule the same way.

Andrew Weissmann: It’s a very difficult argument.

Chris Hayes: Yes, right. Yes. Well, it’s a bad argument.

Andrew Weissmann: Yes.

Chris Hayes: Yes.

Andrew Weissmann: That would be the word.

Chris Hayes: I was overthrowing the government in my presidential duties is a ludicrous argument on its face. I guess the question is like, just to game it out, like if they were like, yes, we’re going to grant cert on this, if they’re going to be super cynical, the conservative majority, and they’re just like we’re going to basically bail out Donald Trump, and we’re hitting pause on this until we can, you know.

But the non-cynical way to do it would be some kind of expedited review.

Mary McCord: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: Like they’re just like, yeah, we’re going to hear it and we’re going to hear it in two weeks or something. I don’t know.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Mary McCord: And the reason I’m optimistic on this point, I think it might derail March 4th, but I don’t think it’ll derail until after the election.

Chris Hayes: That’s the big question, yeah.

Mary McCord: Partly because I do think at least a majority of the justices would feel the gravity of the issue and the need to resolve it quickly.

Chris Hayes: It would just look so craven.

Mary McCord: It would look really bad.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: Yeah, it’ll look really bad.

Andrew Weissmann: And I just don’t think they have enough votes for craven.

Chris Hayes: To be that craven, yes.

Andrew Weissmann: I think they sort of are dealing with the craven on 303 Creative –

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: — on Dobbs, they’re going to save it for that. I just don’t know that they have —

Chris Hayes: Well, but also because they’re also —

Andrew Weissmann: They’re more in the bank on craven.

Chris Hayes: That’s right, and also because there’s real ideological stakes there of things that they, craven or not, believe.

Mary McCord: That’s right.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: They think abortion is not a constitutional right. People in the majority, like, they really believe that. They’ve really believed that their entire adult lives and they’re willing to take the flack for it.

Andrew Weissmann: Do you bail Donald Trump out from prosecution has very different ideological stakes.

Mary McCord: And we’ve seen them move quickly on Trump things before. Remember just a couple of –

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: That’s right.

Mary McCord: — years ago when the House Select Committee sought presidential records from the White House as part of its investigation, even though Donald Trump was no longer president, he asserted executive privilege over that. Biden says, I am the president. I’m not asserting executive privilege. Donald Trump sued. Judge Chutkan had this case. She found there was no executive privilege. The D.C. Circuit had an expedited briefing. They found no executive privilege. It went to the Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court within days denied a stay.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: A stay that would have made, you know, overruled.

Chris Hayes: That’s a great point.

Mary McCord: And I know all these dates because my organization represented the House Select Committee along with the general counsel. And so, this is how this kind of litigation works. You brief the District Court case over Halloween. You brief the Circuit case over Thanksgiving. We briefed the Supreme Court case over Christmas and New Year’s.

So for those of you who want to be a litigator —

Chris Hayes: That’s rough.

Mary McCord: — that’s what your life looks like. But then the Supreme Court acted.

Chris Hayes: Sorry, son.

Mary McCord: They acted fast, right? And the day that they denied the stay, a stay of the Circuit Court’s order, the documents started flowing within hours.

Chris Hayes: So, that is a great reassurance grounded in history, right, which is like they could have been craven there. They could have bailed out. They could have delayed it and they didn’t. I think you’re right. And again, they’re not idiots on the court. I mean, they understand the broader implications of this.

Mary McCord: Sure.

Chris Hayes: They understand where they’re pulling this. They understand these legitimacy questions. Like when I say it out, I think you’re reassuring me that they’re not going to do the worst possible most craven thing.

In terms of the charges themselves, the one that sticks out to me as the most obvious and black and white is the conspiracy to obstruct official proceeding, right? That’s one of them.

Mary McCord: That is one of them.

Andrew Weissmann: I hate to say it. There is —

Mary McCord: There’s an issue in that.

Andrew Weissmann: There’s an issue. I mean, like in the law —

Chris Hayes: Oh, really?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes, in the law, like nothing’s clean.

Chris Hayes: Right, of course, yes.

Andrew Weissmann: There’s always complications. And so, that charge, which is a sort of bread and butter charge in the January 6th cases, that has gone up to the D.C. Circuit. There was sort of a fractured decision on a whole variety of issues, including does Congress count as one of the institutions covered by the obstruction statute.

Mary McCord: As an official proceeding, was that proceeding on January 6th an official proceeding.

Andrew Weissmann: It’s just a statutory issue, was that encompassed. There’s an issue about what is the intent standard. So it’s kind of important because the court was wrestling with both the district court and the Court of Appeals with the issue of could somebody be criminally charged for obstruction if they are waving a sign in the hearing and that causes —

Chris Hayes: Yeah, you don’t want that.

Andrew Weissmann: — it to be delayed. And you’re thinking that if that really wasn’t something that was intended, that’s obviously really different than —

Chris Hayes: Concussing cops.

Andrew Weissmann: Exactly, and that actually, that is the line that the two to one in the circuit said, if there’s violence, we don’t really have to get to the complications because this is so clearly covered.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: So, that will be an issue, but to Mary’s point, that’s going to be after the trial, where Donald Trump gets to say, oh, you charged it wrong –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: — and you should have used this. That should not be decided before.

Chris Hayes: Is there a particular charge that you think is the cleanest or the clearest?

Mary McCord: I think the first, the 371 conspiracy, conspiracy to defraud the government, I mean, that’s a theory that’s been used time and time again, never, of course, in these circumstances because we haven’t seen anything like that.

The obstruction of official proceedings been used with many of the January 6th rioters. It’s been used in other circumstances. I mean, Andrew knows better than anybody’s genesis, so I’ll leave that for him to talk about. But it’s being applied to something new here. It seems very logical that it should apply, but we have lots and lots of cases of just conspiracy to defraud the government.

And when you put together that whole package of facts that are alleged in that indictment, the multi-pronged conspiracy to overturn the will of the people through the fraudulent elector scheme, the pressure on state officials, the pressure on state legislatures, the pressure on Mike Pence, you know, all of this is very much to defraud the government of carrying out an election and a peaceful transition of power.

Chris Hayes: Yeah. Narratively, I like the fact that it’s also the same charge that Mueller brought against Yevgeny Prigozhin who was, of course, the now departed Russian mercenary/war criminal whose =, you know, internet trolls were getting up to all sorts of stuff in the 2016 election. That’s sort of interesting to me.

But it just feels like, you know, the fraud aspect of this seems so obvious to me. Again, like as a non-lawyer, he wasn’t one of the fake electors, but particularly with the fake electors, it’s like you signed a document saying a thing that is just wasn’t true and you knew it wasn’t true, and then you gave it to the government to say this is true. And that just seems like facially fraud.

Andrew Weissmann: I mean, to me there’s a through line when you think about what Donald Trump has done. So, let’s focus on the first impeachment. There the fraud was I want to gin up by withholding vital military aid, which now we understand just how (ph) vital, to get you to say you are doing this investigation because without them I get to then run and attack Biden and his son based on a fake investigation without telling the American public that this was paid and bought for, that I essentially extorted Zelenskyy to do it.

The fake electors, same thing. And one of the things in D.C. that’s charged is in order to get some of the fake electors to go along, they said, “Don’t worry, this is just a contingency if we win in the states.”

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: But that’s not, in fact, how it was going to be used and was used.

The same thing at the Department of Justice. Jeff Clark, who was the acting attorney general for a day, the idea was that he wrote a letter that was, again, to say the Department of Justice has a real investigation when it didn’t –

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: — and had actually found strong evidence of fraud when they did, so they could use it to undermine and convince people in the States to do something different.

Chris Hayes: People talk a lot about this sort of intense frame of mind defense, which I’d love to hear. You guys have talked about this a lot, but for people that have not listened to your podcast or watched shows where you guys have been on, you know, basically the line goes something like this: He’s not a criminal, he’s genuinely delusional and truly is so reality-addled that he thought that it was the case that the Chinese government had used Italian satellites and software coded by the ghost of Hugo Chavez to systematically move tens of thousands of votes away from him. He really believed that. That’s the argument.

And that good luck trying to prove otherwise because the guy’s such a nutcase you’ll never be able to nail him. What do you think of that?

Andrew Weissmann: Defense lawyers used to come into me and make arguments like that as to why their client should not be charged. And I used to give a standard response, which was, that’s a jury argument. Like, go ahead, say that to the jury. Good luck with that.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: I mean, this is where it’s like let’s just grow up. I mean, we are not children. This is the leader of the free world. I mean, this is like the leader of the free world. One of the things he recently said on TV was that he wasn’t even sure what a subpoena required.

I mean, of all people, to your opening, I mean, somebody who has his litigation experience –

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: — I think he would know what a subpoena is, even if he weren’t the leader of the free world. So, that’s like you want to say that you’re completely delusional. Have at it. See if a juror agrees with you.

Mary McCord: And, you know, the other point of it is that even if he firmly and honestly believed that the election was rigged, there are things that he did that you still just don’t get to do, right?

Chris Hayes: Correct.

Mary McCord: You just don’t get to make up false certificates and pressure people to do them and then pressure your vice president to throw the whole thing out, even if you think you won. You know what you can do? You can go bring lawsuits. Do you know what he did? He brought more than 65 lawsuits and he lost them. You know, he lost them.

So, there are ways to deal with that and there are also important tells. To Andrew’s point, there are important tells, some of which are in the indictment, which shows times when he sort of weakly forgot to stick with the program of I firmly believe this. You know, things that —

Chris Hayes: Right, I can’t believe I lost to this guy.

Andrew Weissmann: Or how about telling the vice president you’re too honest.

Mary McCord: Yes.

Chris Hayes: Yes.

Andrew Weissmann: That would be a pretty good sign that he wasn’t delusional.

Chris Hayes: That is truly an amazing line. You’re too honest.

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah, that’s what you want the leader of the free world to be saying to their vice president.

Chris Hayes: How long a trial do you think this is? That first one, that Jan 6 trial?

Mary McCord: Government has said four weeks.

Chris Hayes: Four weeks, I think, is what they’ve said.

Mary McCord: Is that right?

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah.

Mary McCord: You know, it depends because pretrial motions practice where the sides will argue about what can and can’t come into evidence, those can sometimes narrow issues. You know, the government will always start with a very long list of witnesses, and so will the defense. And then sometimes, once they start seeing how witnesses are doing, they’ll kind of jettison a few.

Defense will oftentimes have a long list and then end up calling nobody.

Andrew Weissmann: Zero, right.

Mary McCord: Yeah, because remember it’s the government’s burden.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: If they feel good at the end of the government’s case that the government —

Andrew Weissmann: Why screw it up?

Mary McCord: — why screw it up?

Andrew Weissmann: So Chris, I tend to always tell anecdotes to Mary to her Schagrin (ph). I was about to go to trial for the boss of the Genovese family, Vincent Gigante. And Judge Weinstein, a really revered judge in the Eastern District of New York, said how long is your trial going to be and we said eight weeks. And he said no it’s not. And because he’s such a wonderful man, we were like okay judge, well how long is our trial going to be? Meaning like how long are you going to allow us.

And he said, okay, you said eight. Four weeks. And the best thing that ever happened to us was his saying that, where we paired it down to what we needed. Just, it’s just so much better for the government.

Mary McCord: Lessons learned.

Chris Hayes: I mean that’s the thing about jury trials too is you got an audience. I hope you guys are enjoying this. But you probably start to enjoy it less at hour four, I think.

Andrew Weissmann: Yes.

Mary McCord: That’s right.

Andrew Weissmann: By the way, we’re going to be here for four weeks.

Chris Hayes: Yeah. So exactly, imagine four weeks of this and again it’s like you guys are going to be who’s going to decide. I mean, I think a lot of you defense attorneys would try to strike, actually, just based on your reactions here.

Andrew Weissmann: That would be a great question, because there’s jury questionnaires, it’d be really great to have a question.

Chris Hayes: Who do you want –

Andrew Weissmann: But like are you listening to “Why Is This Happening?”

Chris Hayes: Yes, what podcast do you listen to is actually probably a pretty good one. So it’s, yeah, I think in terms of that. I mean, the other thing that is so wild about it, too, when you think about the actual presenting of that case is, like, Mike Pence is going to be on the stand, right?

Mary McCord: Well, he’s definitely going to be on the witness list.

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah, I think he’s going to be called, yeah.

Mary McCord: He’s pretty key.

Chris Hayes: He’s really key. I mean, that is a wild thing to think about. Like, Mike Pence, the whole so help me God, sits down, like gets, you know, questioned, then there’s going to be a cross of the president’s lawyer?

Mary McCord: Yeah.

Chris Hayes: Isn’t it true you’re too honest? Probably not a question —

Mary McCord: Yeah, I don’t think he’s going to ask that question.

Chris Hayes: — that they’re going to use. There’s something that’s really wild, it’s like a trial of the century, to consider the kinds of people that are going to be on the stand in what is going to be the most significant criminal trial in, again, I think in the country’s history, I don’t think it’s even that arguable.

Mary McCord: I think that’s right.

Andrew Weissmann: Just in a question, yeah.

Mary McCord: And that brings up the fact that you’re in federal court, so unless the Supreme Court decides to change the rules, there will be no cameras in the courtroom, so we’re going to have to be relying on journalists who are in there, you know, reporting out throughout the day about what’s happening. And that’s raising a lot of debate about whether the rule that has been part of the federal rules for a very long time is a good rule.

And I have somewhat mixed feelings about it because I think the whole American public ought to be able to see this trial and probably ought to be able to see almost all trials because it’s transparency. Talk about the double or more than double standard. There’s no better way to kind of test out how our criminal system works than by having people see it.

Chris Hayes: Totally, and particularly because people’s perception of the system are so skewed by either, you know, television representations, maybe “Law & Order”, things like that or the news at night or big trials like the O.J. Simpson trial, which was televised.

Mary McCord: Yep.

Chris Hayes: Yeah, like full transparency to see what’s happening in that room.

Mary McCord: On the other side, Trump, you know, he and his attorneys will try to use it as part of the whole campaign stump speech, right? And so, then you have this concern about it’s just giving them a free platform. So, you know, I come out on the side of transparency because I think for the betterment of the system as a whole, the rules should change. And the Georgia trial will be televised. That’s going to be a very different set of trials. I shouldn’t say trial because already we know and there’s going to be multiple and the first one is right around the corner, a month away.

Chris Hayes: Is there a universe, Spiro Agnew famously was offered basically a —

Mary McCord: Deal.

Chris Hayes: — a deal in which my colleague, Rachel Maddow’s podcast on this Bag Man is amazing about this.

Andrew Weissmann: So good.

Chris Hayes: But if you haven’t listened to it, you should listen to. The details of that are wild.

Andrew Weissmann: Fantastic.

Chris Hayes: Similar to some sort of Robert Menendez details as well. Just real like low level, like just straight up bribery kind of stuff. That’s what Menendez has been accused of by the government, not convicted.

But the Justice Department basically like did a pretty wild thing, which is like resign and we’ll not put you in prison. And I don’t know. Like is there a universe where it’s just like drop out and, no, you can’t do that. Even as I say it, like, of course, you can’t say —

Mary McCord: He just wouldn’t do it. I can’t even imagine him doing it.

Chris Hayes: He wouldn’t do it, but like, I don’t know, man. There was a Rolling Stones story the other day. Have you guys seen this, that he’s asking his confidants and advisors are they going to make me wear the orange jumpsuit. And —

Mary McCord: I’m sure (inaudible) —

Chris Hayes: I don’t know why that’s so funny. It’s amazing to imagine him there, like pounding Diet Cokes and calling one person after another, like, are they going to make me wear the jumpsuit, you know? But like the likelihood of him being convicted in these trials, particularly after four, is relatively high. He’s obviously running for his freedom, but that’s a high leverage bet.

Andrew Weissmann: Well, so if he were to win or to have an ally win, the two federal cases will go away and it doesn’t even involve a pardon. To go to your point, whoever the president is, the executive can just tell this Department of Justice, these cases are over. It doesn’t even matter if there’s been a trial and a conviction, they can say dismiss it. C.E.G. Michael Flynn, so he’s done that playbook.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Andrew Weissmann: And at the state level, if those haven’t gone —

Chris Hayes: They’ll be told.

Andrew Weissmann: Exactly, he will make the argument and there’s some reasoning that the Supreme Court would back him up, that those will wait until after he’s out of office.

Chris Hayes: Obviously, you can’t have the President of the United States sitting in a Fulton County courthouse every day —

Mary McCord: While he’s being president.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: — while he’s being president.

Andrew Weissmann: Right. And the thought experiment there is if you have, let’s say you had somebody in Texas who escaped an impeachment here, deciding I’m going to now indict the Democratic president, you know, the rule would be that that could happen, but that’s going to be told until the person’s –

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: — finished so we don’t have 50 A.G.s running around trying to interfere with the federal government.

Chris Hayes: Right. And so that would mean it would all happen after whatever.

Andrew Weissmann: Exactly.

Chris Hayes: And I think his thinking, he is enough of a sort of day-to-day survivor, right?

Andrew Weissmann: Exactly.

Chris Hayes: He’s not going to think longer term than that. But I do think, I guess the prison jumpsuit story, which lodged in my head, was just because I think that it’s impossible, understandably, for me to conceive of a world in which he ever does a day in prison. Not because I don’t think that he is guilty of the crimes that he’s been accused of. I think he almost certainly is and I think the likelihood of his conviction on them are pretty high, particularly I would say the two federal cases.

I mean, we didn’t even talk about the Mar-A-Lago case, but the evidence there is just like —

Mary McCord: It’s so strong.

Andrew Weissmann: Like before we found out about the new witness, the case was already what’s known as a rock crusher.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Andrew Weissmann: I mean, as a former prosecutor, you look at this, and when people were saying, do you think Jack Smith is going to indict, I was just like on no planet is that not going to happen. I mean, of course he is and the case is so strong.

Chris Hayes: The new witness was a sort of executive assistant who is cooperating, got new lawyers and the detail that came out, which maybe you guys saw, was that he was writing to-do lists on the back of classified documents. Like he had them just around because he has this like really —

Mary McCord: Sketch paper.

Chris Hayes: — yeah, weird neurotic obsession with them, my boxes. She’s the one that called them jokingly in a captured email, his beautiful mind boxes. This is the woman who is now cooperating. And so, because he was so obsessed about having them like Gollum’s ring, like I have to have it near me, that if he needed to write something, he’d just grab a classified doc and write to-do lists on the back of it. So yes, I think the evidence on that case is rock solid.

Mary McCord: I mean, that’s the kind of case that in any other circumstance would plea.

Chris Hayes: Pleas. You plea. You would never take that case to trial. It would be irresponsible.

Mary McCord: That’s why most cases that go to trial are actually harder cases because the cases where your evidence is that solid always resolve.

Chris Hayes: Yes.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Mary McCord: You want, as a prosecutor, to go to trial on that case.

Chris Hayes: Right, this’ll be fun. Right, yeah, exactly.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: Right. And I think that’s clear and I think to the degree there’s questions about the case, it’s timing, judge –

Mary McCord: Yes.

Chris Hayes: — jury pool as opposed to evidence. All of which I think are totally overcomeable. I still don’t —

Mary McCord: I mean, the issue with juries and we’ve talked about this, like I don’t see any world in which Donald Trump is acquitted after trial, because it takes 12 to actually agree. But a hung jury —

Andrew Weissmann: Only John Durham can do that.

Chris Hayes: Yes.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Chris Hayes: Yeah.

Mary McCord: Right. That’s why when you said the 24, that’s what is so remarkable. Those were not hung juries. Those were outright acquittals that John Durham got.

Chris Hayes: Right, good point.

Mary McCord: But it only takes one juror to disagree, you know, with the other 11 to hang a jury. That is not an acquittal. It does not mean that the jury vindicated you. It means you didn’t have 12. It wasn’t unanimous for conviction.

Chris Hayes: Right.

Mary McCord: But that is generally played.

I mean, Bob Menendez, who’s now Sen. Menendez, who’s now been indicted for the second time for corruption and bribery, his first trial, it was not an acquittal. It was a hung jury and the government didn’t retry him. And that gets played like a win by the defendant because the fact is, in many ways it is.

Andrew Weissmann: Right.

Mary McCord: If the government decides not to retry you, you stand not convicted. But it doesn’t mean you’re vindicated.

Chris Hayes: So, your best prediction, we’re going to end on this note, will Donald Trump be convicted of any of the crimes he’s been accused of before Election Day 2024 end?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes.

Chris Hayes: Oh, you guys like that outcome? Huh. I wasn’t sure.

Andrew Weissmann: But I also, just to go further, I think Judge Chutkan will sentence him to jail time.

Mary McCord: Yeah. He goes all the way.

Chris Hayes: That got a gasp. What do you think?

Mary McCord: I think he will be convicted. I think if he is and if it’s on, you know, all three or even just one count, I think that imprisonment will be part of the sentence. But how that gets carried out will be, I think, where a lot of the debate occurs. Like, is that carried out in a —

Chris Hayes: A room in Bedminster.

Mary McCord: Yeah. Well, hopefully not Bedminster, but there are complications. I hope we’re right (ph).

Chris Hayes: Okay. That’s not what I think.

Andrew Weissmann: What do you think?

Chris Hayes: What do I think?

Andrew Weissmann: Yeah.

Chris Hayes: I think I agree. I mean, I’m just a guy with a cable news show. I don’t have any special expertise here. But I think I agree. I think there is some part of me that just worries that there’s going to be some Supreme Court stuff. Someone’s going to come up with something.

Andrew Weissmann: Yes, because that’s what happened.

Chris Hayes: Because that’s the way it is.

Mary McCord: Right.

Chris Hayes: Andrew Weissmann and Mary McCord are co-hosts of the MSNBC podcast “Prosecuting Donald Trump”. Give them a large round of applause.

You guys have been a wonderful crowd. I want to thank “The Texas Tribune”, which is a fantastic journalistic institution that deserves your support. You can listen to “Prosecuting Donald Trump” and this episode of “Why Is This Happening” wherever you get your podcasts.

And for people that may be from other parts of the country or know people in other parts of the country, this is just the beginning of this year’s “Why Is This Happening” live tour. Be sure to join us on October 9 for our next event in Chicago. We’re going to have Trymaine Lee, Vic Mensa and Imani Perry Imani there. That’s going to be a phenomenal conversation.

We will be in Philadelphia on October 16 with Joy Reid, my friend and colleague, and the great author Naomi Klein, whose new book is phenomenal and mind-blowing. And then I’m going to wrap up our tour in New York City on November 12 with a little-known talent that I’ve scouted out. I think you’re going to enjoy. Rachel Maddow will join me November 12 town hall.

Thank you very much, and hope to see you on the road, and download the podcast whenever you can. Thank you all.Chris Hayes: Once again my great thanks to Andrew Weissmann, who was a lead prosecutor in Robert Mueller’s Special Counsel’s Office, also served as Chief of the Fraud Section at Department of Justice. He’s currently a professor of practice with the Center on the Administration Of Criminal Law at NYU. I told you they had very august bios, both of them. And a big thanks, of course, to Mary McCord, a former federal prosecutor for 20 years at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in D.C. She’s now a visiting professor of law at Georgetown University Law Center and Executive Director of the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection.

We had an amazing time in Austin, Texas, at “The Texas Tribune Fest,” got to meet a bunch of you who were there, and I just really enjoyed it. I love meeting listeners of the show. I love doing stuff on stage. I’m a, you know, I’m a ham at heart. It is who I am. I am what I am. So, we’d love to see you out at the three remaining tour dates. There’s only a few tickets left for a few of them. One of them may be even sold out.

So, go to msnbc.com/withpodtour. You can also get in touch with us on X, the site formerly known as Twitter, using the hashtag #WITHpod. You can follow us on TikTok by searching for WITHpod. You can follow me on Threads @chrislhayes and on Bluesky @chrislhayes.

“Why Is This Happening” is presented by MSNBC and NBC News, produced by Doni Holloway and Brendan O’Melia. This episode was engineered by Fernando Arruda and Harry Culhane. It features music by Eddie Cooper. Aisha Turner is the Executive Producer of MSNBC Audio. You can see more of our work, including links to things we mentioned here by going to nbcnews.com/whyisthishappening?

“Why Is This Happening?” is presented by MSNBC and NBC News, produced by Doni Holloway and Brendan O’Melia, engineered by Bob Mallory and featuring music by Eddie Cooper. Aisha Turner is the executive producer of MSNBC Audio. You can see more of our work, including links to things we mentioned here by going to NBCNews.com/whyisthishappening?

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.