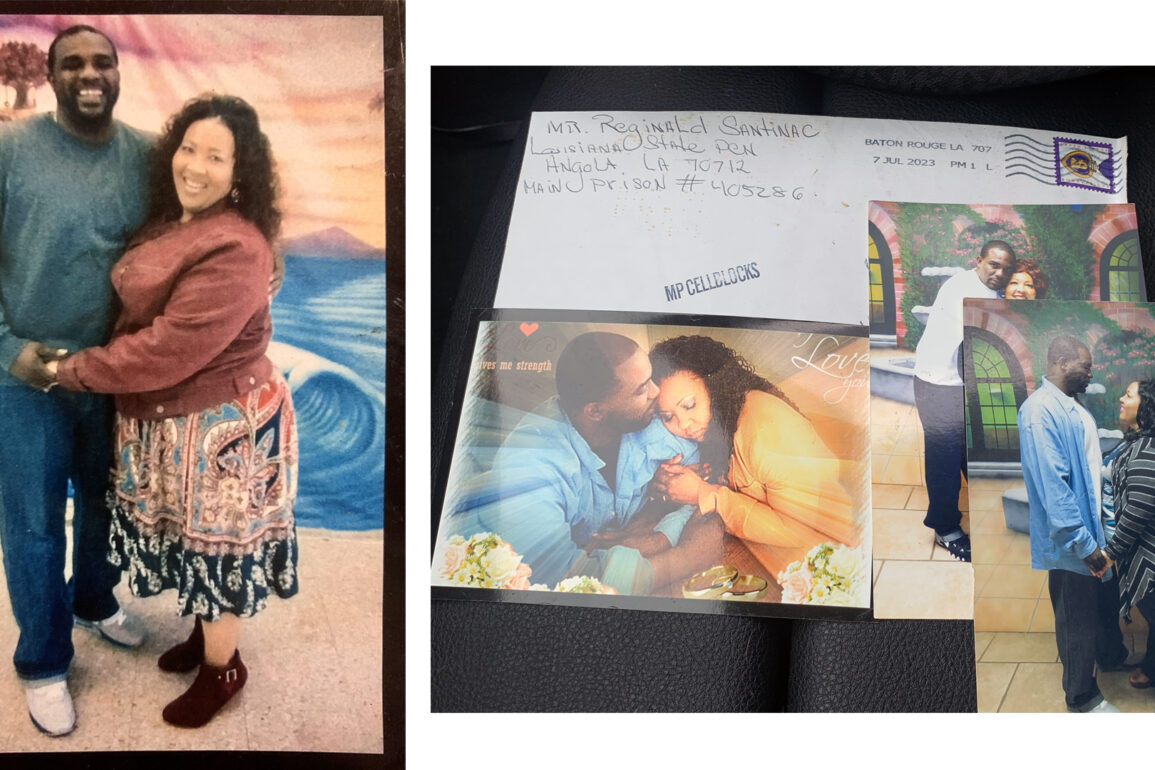

BATON ROUGE, La. — Monicka Henry and Reginald Santinac were high school sweethearts. They met as teens, went to prom together, became adults together. For the last 34 years, they were “husband and wife in every sense of the word,” even after Santinac entered prison at 25.

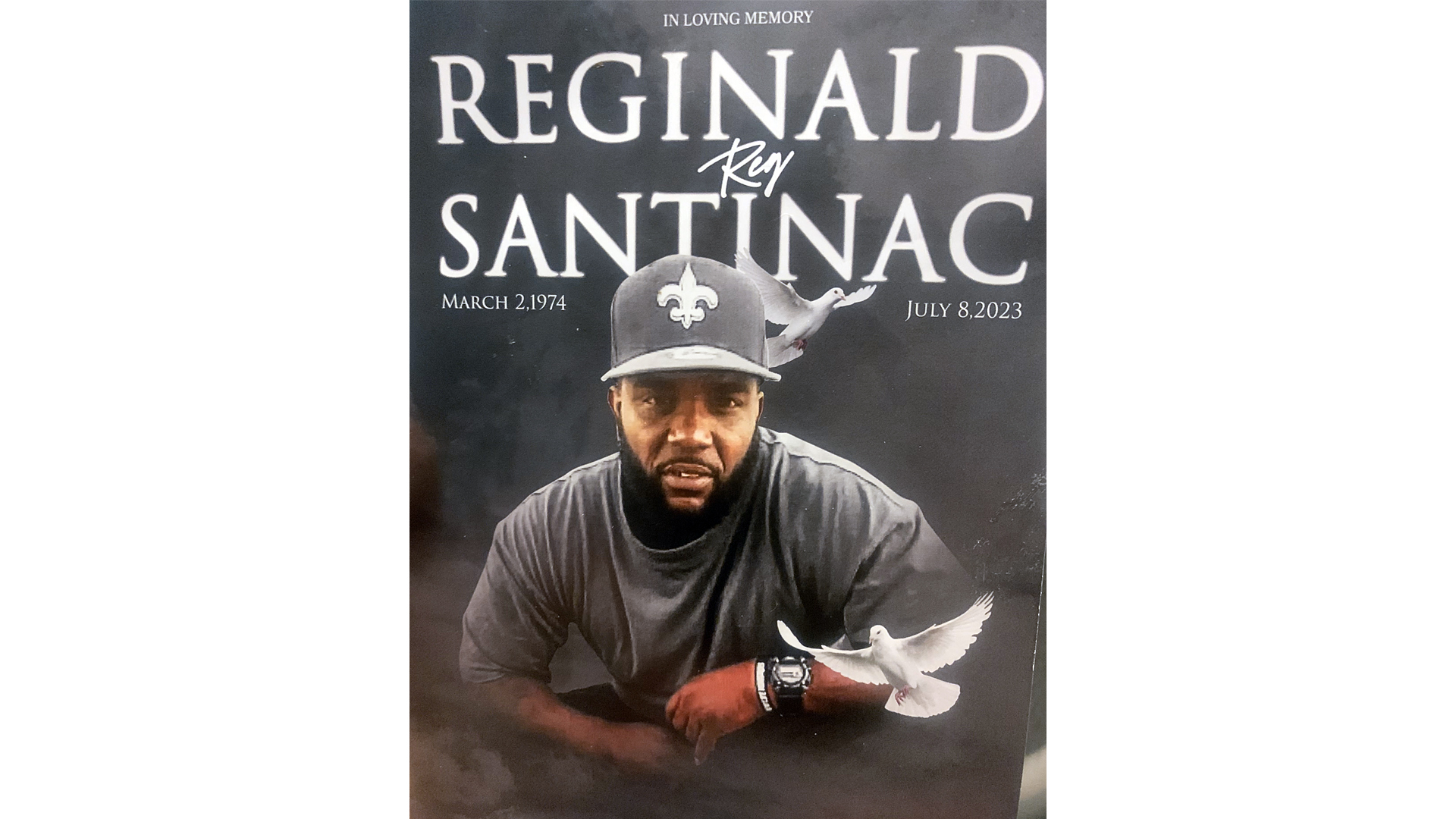

This summer, with the possibility of an early release in the next two or three years, they started to make plans to finally get married. On the night of July 7, they spent time talking by phone about what they needed to do to stay on track. Twelve hours later, Santiac was dead, found lifeless in his prison cell. Henry said he died of a fentanyl overdose.

Though the 49-year-old spent years behind bars, the two made a life together.

“I absolutely did not expect this. I thought they’d give him back alive. I keep saying to myself that I have to accept that he’s not coming back. It’s the hardest thing,” Henry said, as she cried. “We had a real relationship. It wasn’t no jailhouse romance. We didn’t have physical intimacy, but we had something so much deeper. We were soulmates.”

Santinac was serving a life sentence for second-degree murder at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, a facility with a brutal past located on a former slave plantation. A U.S. district judge recently condemned the prison, saying access to medical care was unconstitutionally inadequate and deaths of incarcerated people are the result of “overwhelming deficiencies.”

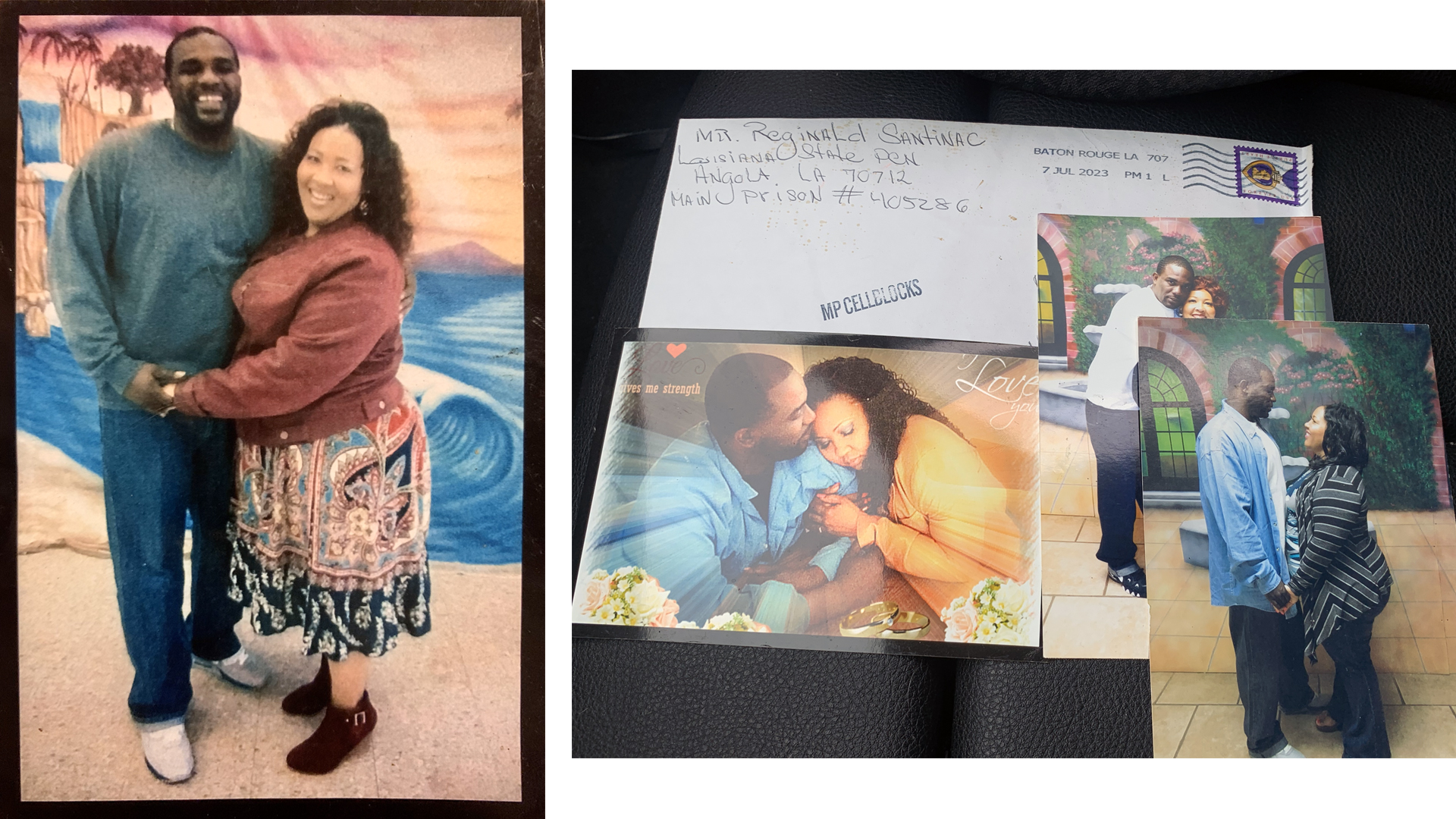

Monicka Henry and Reginald Santinac made the most of their life even though Santinac was incarcerated for the last 24 years. The two spent holidays together taking photographs at Angola but their relationship ended when he died of an overdose in July. The photos, on the right, arrived in an envelope postmarked hours before he died. On one, he wrote, “My Heart and Soul Mate.” Photo courtesy of Monicka Henry

Santinac is one of the growing number of people who have died while in Louisiana prisons, jails, and juvenile detention centers, according to a report released in June from Loyola University New Orleans’ Incarceration Transparency project. Known deaths increased from 129 to 193 — a nearly 50 percent increase — from 2019 to 2021, the report found.

Since 2015, there have been 1,168 total known deaths, according to public records requests filed with more than 120 facilities and six coroners in the state. Loyola’s report is the university’s second analysis of this collected data and the first to include deaths related to COVID-19. While medical conditions remained the primary cause of death, other causes, such as suicides and drug overdoses, reached a high in 2021.

“He was in good spirits. We definitely had a future to look forward to. We wanted a life outside of prison,” Henry said. Santinac got his GED, earned certificates, and completed programs. “He was really doing the work that was necessary to function in society and to get out. How do we go from talking, and then a few hours later he’s gone?”

A funeral program that remembers Reginald Santinac, who died of an overdose while incarcerated at Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola. His wife, Monicka Henry, said the brochure was a tribute to the “love of my life” who was not protected while in state custody. Photo courtesy of Monicka Henry

Santinac had been in lockdown recently, isolated without any contact except prison guards who are expected to do routine checks. After the COVID lockdowns, Santinac struggled and talked openly about how he and others turned to drugs.

“It started to get the best of him. That’s why he started self-medicating, with drugs as a way of coping,” Henry said. “He wasn’t handling it too well. He tried to quit cold turkey. Everyone knew. It’s why he was getting a write-up [for bad behavior],” which led to isolation without phone calls, visits, or other privileges.

“I expected that he would not be dying from drug use and that he would be safe. How did those drugs get in there?” she added.

WATCH: Why dozens of men spent most of their lives in prison after Louisiana reneged on plea deal

The Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections (DOC) disputes that characterization of Loyola’s report, but acknowledges the spike in deaths. Numbers provided by the department show nearly a 44 percent increase in deaths across its eight prisons, rising from 94 in 2019 to 135 in 2021.

“I think it parallels the general population. Our goal with the department is to provide a standard of care that is equal to the community and I think right now, we’re doing that,” DOC medical director Randy Lavespere told the PBS NewsHour. “All deaths are concerning. There’s a department-wide concern. You would like people to do their time and to go home back to their families, and when suicides occur, it’s a black eye for us. Are we not doing what we’re supposed to do?”

Andrea Armstrong, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law and lead author of the report, said deaths in custody “should be rare events given 24/7 staffing, proximity to emergency health care, and the contained environment.”

“When a death behind bars occurs, our state owes the families of decedents and the public a full explanation,” she added.

Yet this information has not been publicly available until now, Armstrong said, because no single authority in Louisiana is required to collect such data.

“Louisiana’s prisons, jails, and detention centers operate without independent oversight, mandatory standards, or public transparency.” the report read. “They are only required to report deaths of people serving sentences to the coroner; parish jails only have to report deaths of people detained pending trial to their local coroner.

Public records compliance is not uniform, and as a result, Armstrong said the “database is admittedly incomplete and presents only a snapshot of known deaths behind bars.”

Henry and prison reform advocates believe deaths like Santinac’s — those not related to medical illness — deserve an independent criminal investigation. Family members wonder who is watching their loved ones.

Santinac’s life matters, Henry said, despite his conviction of a serious crime, as do the lives of all incarcerated or detained people. She said the prison has yet to offer an explanation of how her husband died.

“The jail has never even called me. The only reason I know anything is because incarcerated people from back there begin to share stuff with me,” Henry said. “Why didn’t anyone take it more seriously? People just think, ‘Well, these people are thrown away,’ but we all mess up, we all make mistakes. … He acknowledged the wrong that he did. He took accountability for it. This should not have happened.”

Members of the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison Reform Coalition keep count of the deaths in the local jail, which has experienced a string of in-custody deaths from 2012 to 2020. The roses are labeled with the names of those who died at the prison. Photo courtesy of the Rev. Alexis Anderson/EBRPPRC

Advocates like the Rev. Alexis Anderson, who is a member of the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison Reform Coalition, said there’s “no more fundamental obligation that a prison or jail has than keeping the people inside safe and alive.”

“Prisons are deadly, dehumanizing, and quite frankly, it’s an abysmal failure. If the point of housing people in carceral facilities is restoration, we’re not doing that. We’re separating families. How many more have to die?” she added. “This is a completely solvable problem … We are an outlier in every sense of the word.”

In Louisiana, there are more than 28,000 people currently incarcerated in state and local facilities, according to the state’s corrections department. Louisiana has not only the highest per-capita incarceration rate, according to a Prison Policy Institute analysis of federal and state data, but also the highest in-custody mortality rate in 2019.

“Our state and federal government are constitutionally obligated to provide safe and humane conditions for incarcerated people,” said Armstrong, a national expert on prison and jail conditions. “The hope is that by publishing this information, administrators of this facility can recognize the ways in which they can do better.”

The Orleans Justice Center, operated by the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office, has been under a federal consent decree since 2013 after the jail’s conditions were deemed unconstitutional. Federal monitors overseeing the jail’s compliance said in 2021 that the facility has regressed. Photo by Roby Chavez/PBS NewsHour

When Congress passed the Death in Custody Reporting Act more than two decades ago it was an initial step toward more accurate and complete information regarding this data. But Armstrong said a 2013 update to the law now limits the specificity of the federal data that is collected, and worries it will affect the ability to obtain information. The state legislature could pass a law empowering an agency, such as the Louisiana Department of Health, to collect that data, she added.

The U.S. government doesn’t know how many people die in law enforcement custody or while imprisoned each year, according to a 2023 report published by The Leadership Conference Education Fund and the Project on Government Oversight. They estimate the federal government likely undercounted deaths in custody in 2021 by nearly 1,000 when compared to other public datasets.

Louisiana uses local jails operated by local sheriffs’ departments to house people serving their state sentences. More than half of the people serving time for state sentences are in local jails. The Loyola report separates people who died in state-run facilities from those who died in parish-run facilities, which often lack services for people serving long-term sentences, such as access to appropriate health care, programs that can reduce recidivism and skills training.

Researchers found that suicides, drug overdoses, and deadly accidents were worse in Louisiana’s local parish jails, which house both people convicted of crimes and those awaiting trial. The report found that while parish jails accounted for 25 percent of all known deaths from 2015 to 2021, they accounted for 61 percent of suicides and 54 percent of overdose deaths. The data from Armstrong also shows that one in four incarcerated people killed due to violence were housed primarily in local jails.

Thirteen percent of all known deaths were of people in local jails being held pre-trial, meaning they never had their day in court.

The Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association did not return messages seeking comment about the data that suggests parish jails are less safe than state-run prisons.

A 2020 Reuters report highlighted a broken system of federal oversight of local jails. It found nearly 5,000 people who had not been convicted died between 2008 and 2019. The investigation also found that the 3,000-plus jails in the U.S., which are run by county sheriffs or local police, are often understaffed and underfunded.

Advocates believe many jails lack oversight and are not subject to any enforceable standards for their operation or the healthcare they provide.

While the state’s corrections department makes a distinction between the deaths of people in state prisons and pre-trial detainees in jails, Armstrong said when both groups are housed in the same facilities, officials can’t separate the deaths as two distinct populations if they plan to prevent more deaths from happening.

“I’m unaware of a jail that provides materially different conditions for people who are convicted versus people who are being detained for pretrial,” Armstrong said. “They don’t have separate policies governing visitation. They may be on separate tiers, but the food that they are served is the same. The medical care that they get is the same. The security that supervises them, enforces the rules, and controls the perimeter of the facility is the same.”

“Where we see that more of those are happening in jails as compared to prisons that tells me that there’s something going on in the jail,” she added.

Armstrong said the data could be used by prison and jail administrators to identify best practices, promote cross-facility learning, and replicate implementation.

WATCH: Supreme Court decision limits how prisoners can challenge their convictions

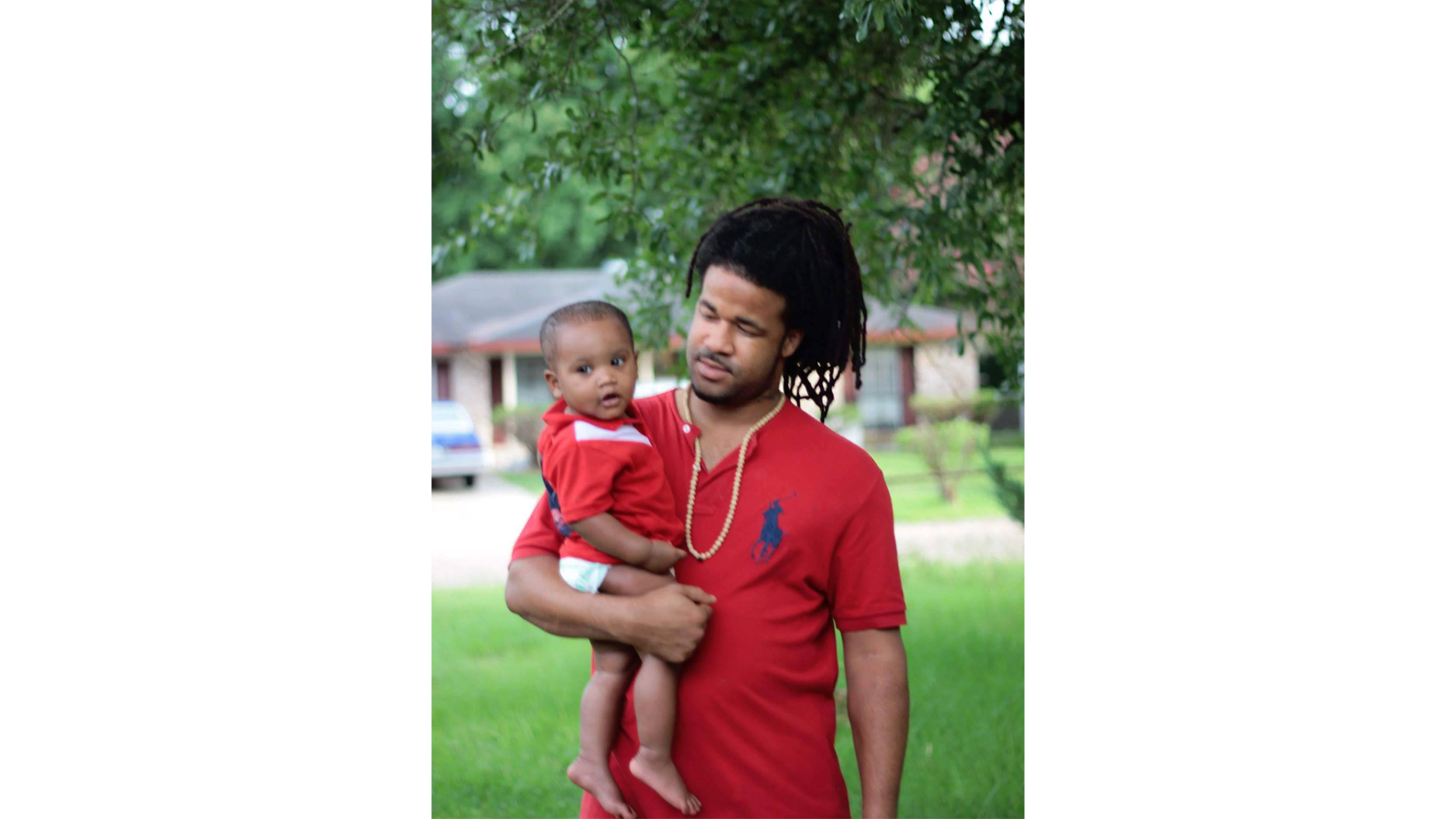

Linda Franks has been asking for accountability since 2015, when her son, Lamar Alexander Johnson, was pulled over during a traffic stop for a tinted windows violation and arrested on an old warrant for writing bad checks. Days later, he was discovered dead inside his cell at the parish jail, The Advocate reported. His death was ruled a suicide, but family members don’t believe the investigation was thorough.

Since then, Franks has been fighting, protesting, and showing up in court to help people stay out of pre-trial detention, fearing others would meet the same fate as her son. She said an outside review of all the deaths is necessary.

Lamar Johnson, seen here with his child, was arrested in 2015 after he was pulled over for a minor traffic infraction. He was on his way to pick up his grandmother from her dialysis treatments. After four days in the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison, the 27-year-old hanged himself inside an isolated cell.

Not much has changed in eight years. Franks, a founding member of the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison Reform Coalition, is now helping a family who has experienced a similar death of a loved one being detained in jail because he couldn’t post bail.

Kaddarrius Cage was experiencing a severe mental health crisis when he entered the East Baton Rouge jail on May 19 for stabbing his stepfather during an acute psychotic episode, according to his family.

Cage’s mother, Kimberly Cage-Williams, did not believe the jail was the right place for him but was told by police she had no other options. She thought Kaddarrius, who had paranoid schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, should be hospitalized so his normal medication schedule would not be disrupted. For almost two weeks, Kaddarrius’ mother said she got no updates from the jail and couldn’t bring medicine to her son.

“One lady even went as far as to tell me, ‘Do you think that we risk a lawsuit by not taking care of your son?’” Cage-Williams said. “They all assured me that he was on suicide watch, he was in a cell by himself where he couldn’t hurt himself. But I guess none of that was true.”

The morning of his death, Kaddarrius underwent a mental health evaluation, according to the sheriff’s office. Hours later he’d be hospitalized and put on life support, dying days later.

Kaddarrius Cage is seen here with his mother, Kimberly Cage-Williams. Cage was recently found dead in his East Baton Rouge Parish Prison cell, 12 days after he was arrested in May while experiencing a severe mental health crisis. Between 2012 and 2016, the EBRPP had a death rate more than twice the national average, according to a Reuters analysis. Photo courtesy of Cage-Williams

Kaddarrius died by suicide, according the sheriff’s office. However, his mother believes officials were not transparent in the investigation.

“I cry every day. I miss my son. Because of their carelessness, I will never see my son again,” Cage-Williams said. “I didn’t think my son was going to jail to die, and I expected that they would take care of him. I don’t want this to happen to nobody else’s child.”

Franks is angry about the spike in deaths reported by the Incarceration Transparency project, but believes the group’s work sheds new light on prisons and “archaic jails” that operate under “the old standard of oppression and violence towards those who have committed or have been accused of committing offenses.”

“It makes you feel as though there’s still no sense of care, but also with that came a sense of hope. If the numbers are rising, there has to be more scrutiny. There has to be a larger call for accountability and for transparency of what is actually contributing to these numbers spiking,” Franks said.

Researchers who collected and analyzed the data said the changes prisons and jails made to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the environments in which these deaths occurred. Facilities suspended visitation, learning programs, and outdoor recreation. Staffing challenges during that time also contributed to the pandemic-related changes that could have played a role in the spike in non-medical deaths recorded in 2020 and 2021.

The project, though, stops short of drawing certain conclusions about the deaths.

“I think there was a very conscious decision in starting this project that we don’t make any findings about whether the deaths are preventable, whether there were omissions or errors by the facilities in terms of any of the deaths,” Armstrong said. “We don’t do that because we don’t have the information that would be needed to draw that conclusion.”

A view of a guard tower inside Angola Prison. Photo by Giles Clarke/Getty Images

While more people are dying behind bars in the state, the Louisiana Department of Corrections believes “there’s a lot of biased aspects of the report from people that have been on committees against us” and it was not “written in a positive manner,” Lavespere said.

Armstrong defended the report and acknowledged that one group that has pending litigation helped law students file public records requests, but that they did not have any role in the report’s analysis or conclusions.

Lavespere also said those incarcerated at the state’s eight prisons are a higher-needs population with serious medical and mental health issues, noting that deaths have increased due to an older population and the advanced nature of disease when people are incarcerated.

For example, he said, the leading causes of death among those incarcerated are heart disease and cancer. The report shows an overwhelming amount — about 80 percent — of medical deaths occur at DOC facilities. This compares to 71 percent of all deaths due to all causes that occur in state facilities.

“Any time when the locals have high medical needs or mental health issues, we bring those into the state facilities because that’s where the most robust care is, so that’s also why you’re going to see that [higher] concentration,” said Natalie LaBorde, executive counsel at the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections.

She added that most people now go through two reception centers where those convicted are given a full assessment, including education, medical, mental health needs, and then determine the right placement.

As the chief medical director, Lavespere said the corrections department has made adjustments to slow the staggering number of people who die in Louisiana prisons. Medical costs have grown from $94 million to $100 million since 2017, according to DOC figures. He said he personally completes death reports on every person who dies.

“We took control of our own health care. We pay for our own individual health care through the department of corrections. We have private urologists and private podiatrists come. We have a contract with an orthopedist that comes. We staffed up on-site. We do a lot of on-site clinics and are using electronic records. There’s a continuity of care that exists that I think is very good,” Lavespere said.

Armstong points to specialized programs for substance abuse and narcotics abuse as well as for sex-related offenses as well as a new dialysis unit. Still, she said having high-needs groups should not excuse the deaths.

“What they’ve demonstrated is they are capable of pivoting as needed. It’s just a question of whether that is an ongoing evaluation,” Armstrong said. “The obligation to provide the care doesn’t depend on the types of needs that are presented.”

As for drug overdose and violent deaths, Lavespere said “fentanyl is a big problem [for] the free world, and it’s a problem within the prison setting.”

He said 75 percent of overdose deaths have been fentanyl-related.

“There’s a lot of measures that we are taking to address the opioid crisis internally from self-reported detoxing to awareness regarding the dangers of fentanyl. It’s a big priority,” said LaBorde.

However, Lavespere could not cite any specific plan, such as collaboration with security, to address the influx of drugs into state facilities as a health crisis.

Advocates like Anderson believe there needs to be accountability in the numbers.

“How in the world can somebody die of an overdose of fentanyl in a facility where there should be somebody no less than a minute away from them?” Anderson said. “So one of the problems is that without having a real investigation, what you also don’t get is an after-action plan.”

The one thing officials should be able to assure, when somebody goes to a state-run facility or local jail, is that they’re not putting them in harm’s way, she said.

If you or someone you know is struggling with depression or suicidal ideation, you can call 988 to access the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline or find help online at https://988lifeline.org/.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.