Executive Summary

- Bringing Vladimir Putin and his administration to justice for crimes committed throughout the course of the ongoing war in Ukraine is an issue more from the realm of diplomacy than that of law. There are a wide range of courts that can judge Russian officials for their crimes in Ukraine. These include the International Criminal Court, any ad hoc tribunal created under different aegis, as well as the national courts of Russia, Ukraine, or a third country.

- To transform this idea into reality in due course requires, above all, political will and skillful diplomacy.

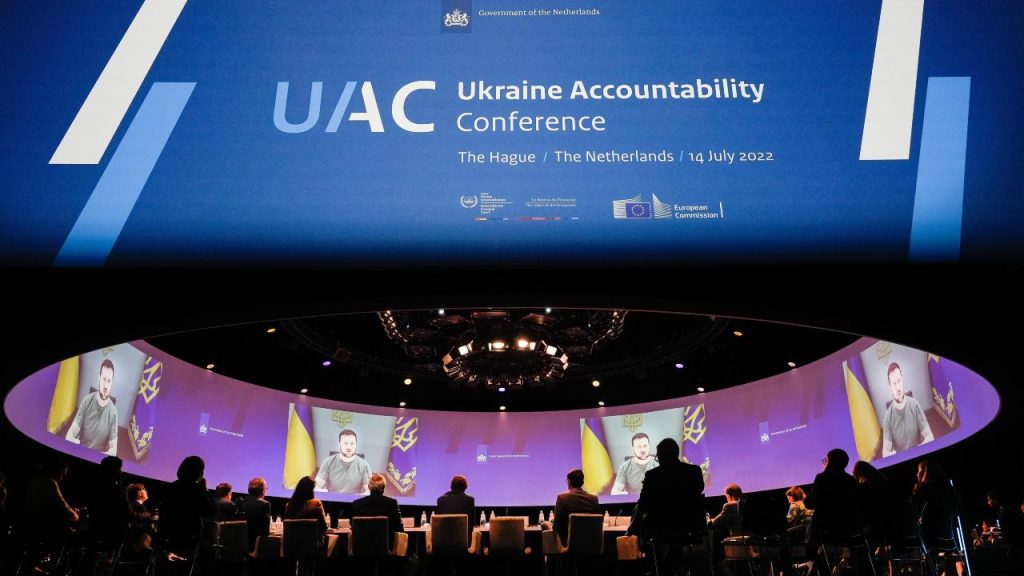

- The idea holding Russia accountable for its crimes in Ukraine enjoys global support, and the collection and documentation of the evidence has been underway by both Ukrainian and international experts and law enforcement organizations involved in the process. To show support for this, a landmark decision has been made with the creation of the International Centre for the Prosecution of the Crime of Aggression Against Ukraine at Eurojust. This process is of extreme importance and needs to be continued.

- Nothing prevents a post-Putin Russia from accepting the idea of a tribunal as part of the reconciliation process; nonetheless, its refusal is not critical, as the world has a range of legal and political instruments to ensure that this tribunal takes place if there is enough political will for it.

- In this context, the organization of the tribunal requires further diplomatic steps as well as the continuous pressure of sanctions on Russia to ensure the minimum necessary level for its cooperation.

Introduction

On March 17, 2023, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin, accusing the Russian president of alleged war crimes involving the forced deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia.

Holding high-ranking Russian officials responsible for criminal acts committed during the course of the war in Ukraine is one of the four key points of the “Ukrainian terms for the just peace.” Setting aside other aspects of Russia’s responsibility for the war in Ukraine, this paper concentrates on this particular issue, examining inter alia Ukraine’s official proposal for the establishment of a special tribunal for the trial of the Russian leadership. This proposal has not been widely presented to the public. Revealing its major provisions here will facilitate a better understanding of the issues in focus.

The first part of this paper examines the existing international judicial system in search of an answer to a practical question: Does the world really need another international court to deal with the war in Ukraine? The second part analyzes four options to judge Putin’s administration for war crimes committed in Ukraine: the ICC, an ad hoc tribunal, national courts of Russia, and national courts of any other country. The third part of this paper deals with practical aspects of the arrangements for the tribunal, such as proper timing, the format of diplomatic efforts, and the legal formalities that need to be taken into account.

This paper argues two principal points:

- Although nothing prevents the establishment of an ad hoc tribunal, the world already has a judicial machinery to punish international war criminals. Thus, bringing Putin and his administration to justice is an issue that is more from the realm of diplomacy than that of law.

- The practical aspects of such a tribunal will require fine-tuning after the end of the war and the transformation of the conflict into a post-war political settlement.

Does the world need another court?

In an effort both to ensure justice for Russia’s victims and to deter further aggression by Russia or other states, Ukraine has proposed the creation of an ad hoc Special Tribunal for the Punishment of the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine. While this may seem politically and rhetorically expedient, such a move would contribute to the fragmentation of international law, erode the legitimacy of existing international courts, and reinforce damaging misconceptions about how international law can and should function. Instead, diplomatic efforts should focus on using the preexisting institutional capacities of the ICC.

Argument #1: An ad hoc tribunal for Ukraine will further fragment international criminal law and its selectivity.

The international tribunals of the first generation — Nuremberg and Tokyo — firmly made inter alia two points that are perfectly relevant to the ongoing war in Ukraine: first, an aggressive war is an international crime, and second, the concept of state immunity is not absolute. Both concepts were placed in the foundation of international criminal law, dealing with the crime of aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. After the United Nations Security Council established the second generation of international criminal tribunals in the 1990s — for Rwanda and Yugoslavia — the world witnessed a wide range of “hybrid” regional courts and tribunals established on different legal basis, with different jurisdictions, with or without connections to United Nations (UN) institutions. The subject and ratione temporis jurisdiction of all these courts differs greatly as well — from a particular assassination case for the tribunal in Lebanon to the case of genocide for the court in Cambodia. The rapid rise in the number of such ad hoc tribunals with limited and very different jurisdictions leads to the fragmentation of international law, particularly from the perspective of the formation of different judicial (precedents) practices.

The parallel process of the establishment of the ICC as a permanently functioning institution with universal jurisdiction for four groups of the gravest international crimes and close relations with the UN system was a rational response to this trend from the perspective of the consolidation of international criminal law. Moreover, the idea of a treaty-based permanently functioning international criminal tribunal is in line with the other endeavors of establishing public order in the international arena, such as the concepts of erga omnes, jus cogens, common heritage, etc. In this sense, the ICC’s jurisdiction would ideally evolve into a global one, gradually expanding the list of countries that would voluntarily join it.

Studying the Ukrainian proposal of an ad hoc tribunal from this perspective, it should be admitted that it is another step toward the fragmentation of international law. Not only is the tribunal proposed for a particular case, but it is also suggested that it deals exclusively with one crime — the crime of aggression, thus excluding three other groups of crimes. Such limitations are inconsistent with the fact that Russians have committed all four groups of crimes, including war crimes and crimes against humanity, in Ukraine. There is certainly a reason for a tribunal from a procedural perspective, which is the second argument against the establishment of an ad hoc tribunal — a jurisdictional overlap with the ICC. The creation of a tribunal for Ukraine will be another step toward turning the idea of ad hoc tribunals into the new normal for international criminal law, which contradicts the need for its consolidation.

The tribunal proposal has received an ambiguous response because of the abovementioned reasons. While the idea of holding Russia accountable for its flagrant breach of international law is well accepted in the world, there is little agreement on the practical aspects of its implementation. From the practitioners’ perspective, ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan has stressed the need to rely on the already functioning institutions, reaffirming the ability of the ICC to handle this case. This claim was reinforced by the ICC’s March 17, 2023, arrest warrants for Putin and a member of his administration in connection with the forced deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia. In the academic community, Khan’s fears about the fragmentation and selectivity of international law that the establishment of a new tribunal will facilitate are echoed.

Argument #2: The tribunal creates overlap with the jurisdiction of the ICC, thus, eroding its jurisdiction.

Although the Ukrainian proposal directly stipulates that “the establishment of the Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine will not affect the jurisdiction of the ICC, but will only complement its important work,” numerous cross-references demonstrate the opposite. The tribunal is to be based on “the norms and approaches applied by the International Criminal Court and set out in its Rome Statute” and will deal with the crime of aggression as defined in Article 8 bis of the Rome Statute of the ICC.

The crime of aggression is part of the ICC’s jurisdiction, although subject to the ratification of the corresponding amendments. As previously mentioned, the Ukrainian proposal compromises references to other crimes that are in the ICC’s jurisdiction in its endeavor to establish procedural grounds for a new ad hoc tribunal. Such an approach both weakens Ukraine’s proposal due to its own internal limits and emphasizes the great overlap of the jurisdictions of the proposed ad hoc tribunal and the ICC.

Argument #3: An incorrect perception.

The idea to establish a special tribunal is based on the Ukrainian government’s incorrect perception that “currently there is no international court or tribunal that could try Russia’s top political and military leadership for committing the crime of aggression against Ukraine.” This statement is not accurate as is evident from the existence of the ICC. However, the ICC is currently not an option for this particular case due to the lack of its jurisdiction. Thus, the Ukrainian proposal recognizes the establishment of the special tribunal as the only possible option, overlooking the option of unblocking the jurisdiction of the ICC. Nevertheless, this option exists and is much more rational compared to establishing a brand-new institution with all the associated time, organizational, and financial expenses.

From a practical perspective, the issue of the ICC’s jurisdiction can be resolved through diplomatic efforts if there is political will. Obviously, this cannot be expected from Putin’s administration, but the trials do not have to take place tomorrow. As will be discussed in further detail below, the practical implementation of the idea of the tribunal in any format requires a certain degree of cooperation from Russia. The issue of the ICC’s jurisdiction should also be a part of negotiations with the post-Putin government of Russia.

Discussing in this context the issue of ratione temporis jurisdiction, one should admit that post-factum agreement does not create any legal problem for international criminal tribunals. In fact, most of them were created post-factum, which demonstrates that a priori approval does not have any critical influence on their jurisdiction. By their charters, all the tribunals obtained jurisdiction over the corresponding periods in the past, fitting the time of the conflicts in focus.

What are the options?

The creation of a new court is, in fact, only one of several viable options, which include the ICC, an ad hoc tribunal, and the national courts of either Russia or any other country (Ukraine, for example). This paper analyzes these options from the perspective of both the general theory of international law and the issue of overcoming the existing lack of Russian consent for a trial.

The ICC

The ICC is the most rational option from several different perspectives. It is an already existing and fully functioning institution. The trial of Russian officials at the ICC would be beneficial from the perspective of holding those people accountable for their crimes on the universal principles of the court’s jurisdiction. Another benefit of the ICC’s jurisdiction is a much wider examination of this case including all four groups of crimes, instead of splitting it into two separate cases. Moreover, trying Russian officials at the ICC in the same manner as officials from other countries can contribute to a better understanding of the practical aspects of the sovereign equality principle. From a theoretical viewpoint, the ICC’s involvement in this case would play a significant role both for the consolidation of international criminal justice and further steps toward the establishment of a rules-based public order of international law.

The evident problem with trying Russian officials at the ICC is the existing rules of the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the court. The combination of Articles 11, 12, and 24 of the Rome Statute excludes the ICC from this trial as Russia never ratified it and even withdrew its signature in 2016. However, as an institution, the ICC can be used for trial in case of a) post-factum agreement from Russia on the jurisdiction of the ICC and b) ICC machinery used on a different set of rules — i.e., a different charter similar to that usually adopted for ad hoc tribunals.

Post-factum Russian agreement

The Rome Statute has its own rules for the ratione temporis jurisdiction. However, the ICC is an institution established under international law, with the sovereign will of the states as its basis and the formula consensus facit jus being one of its basic principles. If Russia recognizes the jurisdiction of the ICC for its citizens, then the jurisdiction rules should be used mutatis mutandis the Russian declaration. Two Ukrainian declarations as to the post-factum recognition of the ICC’s jurisdiction made on the basis of Article 12 (3) of the Rome Statute are practical examples.

Different set of (jurisdiction) rules

There is nothing in international law that prevents the adoption of a new document as the basis for the trial of Russian officials. This can be a separate charter for the particular case of Russian crimes in Ukraine or a document that authorizes the use of the Rome Statute with adjusted jurisdiction rules for this very case. Such a document can be adopted in the form of

a) a decision of an international conference (congress) that is compulsory for Russia due to either its a priori agreement for this or due to the statute of such a conference (congress), or

b) a decision of an international organization(s), either global (UN) or regional (Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, etc.) or different combinations of such organizations.

As for the practice of the UN Security Council establishing international criminal tribunals, it is worth noting that there is nothing in international law that formally establishes this monopoly. The only reason that this track was selected is the obligatory nature of the Security Council’s resolutions, but obviously, it is not the exclusive way to make a document binding for a particular country. Practical examples include the Special Court for Sierra Leone (2002) or Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (2003), established by treaties between those countries and the UN without any involvement of the Security Council.

An ad hoc Tribunal

The option of an ad hoc tribunal is also valid, as such a tribunal can be established under different aegis. In establishing the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, the UN Security Council relied upon a rather general tool kit to deal with the challenges to peace and the acts of aggression. However, the UN is not the only organization in the world that deals with issues of international security. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), for example, is a regional European organization whose “first basket” (military and political dimension) is focused on international security, with the general goal of dealing with conflicts and their consequences in Europe. Practical examples of regional organizations playing a key role in establishing tribunals include the Extraordinary African Chambers (2013) and the Kosovo Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office (2017).

A rather powerful option can be an ad hoc tribunal under a common aegis of the UN and European regional organizations. In this context, there is no formal requirement for support of the Security Council, as it is the UN General Assembly that “may discuss any questions or any matters within the scope of the UN Charter.” Although General Assembly resolutions are only recommendations, they can be a powerful instrument in support of the idea of such an ad hoc tribunal, should there be enough political will and diplomatic effort. A practical example is the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (2003), whose establishment was guided by General Assembly resolutions.

National jurisdiction

Although this option may sound controversial, there are a number of arguments for it. As the focus of this paper is exclusively on personal (criminal) responsibility of the Russian officials, there is no reason to exclude national jurisdiction from the options. Indeed, it does not matter if the criminals spend the rest of their lives in a Dutch or Russian prison. It should be noted that international criminal justice has been hand in hand with national criminal justice ever since the Moscow Declaration of 1943. This tradition was continued by subsequent international tribunals, thus emphasizing the principles of complementarity, and keeps international justice as the last resort. From a practical perspective, there have been several cases where dictators were judged on the basis of national jurisdiction with rather grave consequences to their personal destiny. So, national jurisdiction does not automatically imply any advantages for the defendants in terms of court proceedings or sentence. Instead, it easily resolves a number of sensitive issues, offering rather elegant solutions.

In terms of national jurisdiction, there are two options that are both valid. The first option is the jurisdiction of Russian courts and the second a national court of any other country. Both options are analyzed below.

Russian jurisdiction

The fact is that the Russian state and the people of Russia are among the victims of the crimes of Putin’s regime. Moreover, there are four practical reasons for opting for the jurisdiction of Russian courts. These are discussed below.

Time factor. Peace negotiations, international conferences, and the establishment of an international tribunal usually take years if not decades. Will any of the accused still be alive for the proceedings? National procedures are usually much shorter. This greatly increases the prospects of the proceedings being completed while the defendants are still alive to hear the verdict. As citizens of Russia, Putin and his accomplices are under the jurisdiction of Russian law. No international formalities are required to start proceedings against them.

Allowing Russia to save its face. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, there were some who emphasized the importance of allowing Putin to save face. There was an acknowledgment of Russia’s national pride and its importance to Russia’s political elite. From this perspective, a national trial for Putin’s regime is a perfect solution as it formally excludes any external involvement.

On Sunday, October 02, 2022, in Krakow, Poland. Credit: Artur Widak/NurPhoto

Historical aspect — to finish unfinished business. The selectivity of the Nuremberg tribunal allowed the Soviet Union to avoid discussing a number of its own notorious acts. This led to an underestimation of the Soviet Union’s role in the initiation of the Second World War with its aggressions between 1939 and 1941 and numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity that followed. Moreover, the inability of post-communist Russia to establish a trial for the communist regime with its numerous crimes, and the fact that the Soviet secret police agency, the NKVD, the forerunner to the KGB, was the primary executive power for those crimes, has often been recognized as one of the key factors for the current KGB retaliation in the form of Putin’s authoritarian regime. This retaliation has brought back recognizable attributes of some communist regimes — i.e., the refusal of basic civil freedoms, mass crimes against humanity, and aggressive wars. From this perspective, a national trial for Putin will set an important precedent of dealing with criminals who abuse state power for personal purposes. National condemnation of Putin’s regime will also mean official condemnation of practices associated with some communist regimes and the KGB, thus reaffirming the minimum basic requirements for the structure of state power.

Zero point to make. An obvious benefit of a Russian national trial for Putin’s regime is an opportunity for Russian society to make a distinction between Russia and Putin, thus establishing some basic ground for the post-Putin period. Moreover, the condemnation of Putin’s regime by the Russian judicial system would be viewed as a test of the intent of Russian society to start on the path back to normality both in terms of the internal restructuring of state power and the return of Russia to the international community.

Any other national jurisdiction

The Ukrainian proposal contains a reference to Ukrainian national jurisdiction, however, without details of its division between the international and national levels (which Russian officials should be tried by which courts). Certainly, Ukrainian national courts can judge Russian officials due to the principle of territorial jurisdiction, yet it is not the only principle available. There are two other principles of criminal justice that matter in this context. The first is the principle of national jurisdiction in crimes against the citizens of a particular country. This principle was practically illustrated by the Spanish arrest warrant for the now-late Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. The grounds for the prosecution of Pinochet was the fact that a substantial number of citizens of Spain disappeared in Chile during the time of his rule.

The second principle of criminal justice is the principle of universal jurisdiction as specified in the preamble to the Rome Statute. It implies that every country in the world has jurisdiction to judge defendants accused of the gravest international crimes by its national courts. This principle was included in the criminal legislation of many countries, thus creating a rather effective mechanism of criminal prosecution. Practical examples include the numerous cases against war criminals that were prosecuted all over the world.

Some countries adopted special legislation the principle of universal jurisdiction into their national legal systems. An example of this practice is the special Code of Crimes against International Law adopted by Germany in 2002. A number of verdicts adopted by German courts are based on this code.

In the context of universal jurisdiction, one should certainly mention ex officio immunities of state officials, as recognized by the UN’s International Court of Justice (ICJ). In its 2022 judgment, for example, the ICJ protected the immunities of Congolese ministers of foreign affairs from the jurisdiction of the foreign national court. This decision implies ex officio immunities for other high-ranking officials acting on behalf of the state. However, there are two points to mention in this regard. First, the immunities are not granted for “personal benefit, but to ensure the effective performance of the functions on behalf of the respective States.” Thus, the immunities do not release officials from criminal responsibility, nor do they offer lifetime protection from prosecution. These privileges are limited to politicians in office. They are not valid after their term in office is over. Second, the concept of immunities does not have an absolute nature as the practice of numerous international tribunals has demonstrated. Moreover, the erosion of this concept in recent decades is one of the trends in international law. One of its illustrations is the case of former Sudanese dictator Omar al Bashir in which the ICC stated, “There is neither State practice nor opinio juris that would support the existence of Head of State immunity under customary international law vis-à-vis an international court. To the contrary, such immunity has never been recognized in international law as a bar to the jurisdiction of an international court.”

The practicalities of justice

Bringing the Putin regime to justice for its crimes in Ukraine has at least three practical elements. First, the idea of holding Russia and its administration accountable for crimes committed during the course of the war in Ukraine has already received near universal support.

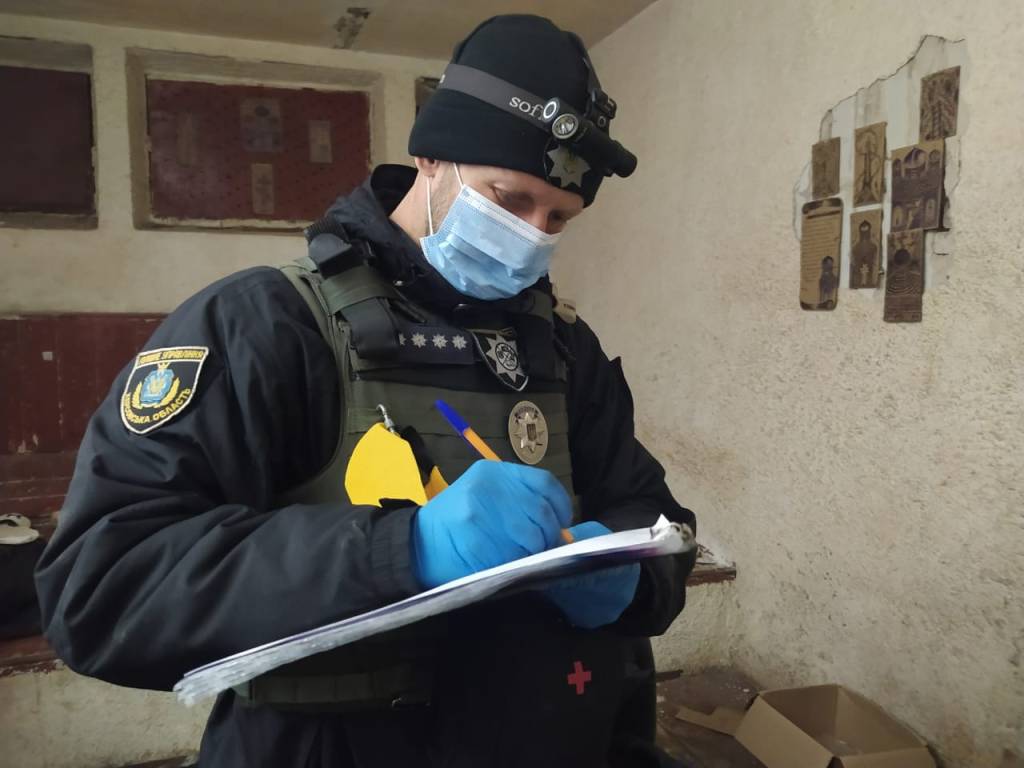

Second, the practical work of the collection and documentation of evidence of these crimes is underway with both Ukrainian and international experts and law enforcement organizations involved in the process. Third, the organization of a tribunal requires a certain degree of cooperation from Russia due to the fact that all of the accused as well as most of the Russian documents related to the war are in Russia. Both the ICC’s rules and the Ukrainian proposal stipulate that the accused are to be tried in their (those who have been indicted for the crimes) presence. Thus, no trial is possible unless the Russian officials are extradited to the jurisdiction of the tribunal.

Another perspective of the debate is the fact that the current situation with the tribunal is ad hoc anyway, due to the absence of any existing general jurisdiction as well as any public order of international law. With diplomacy being the primary instrument for its development, it should be mentioned that the situation is dependent on the actual outcome of the war, both in a military and political sense. Therefore, the best time to fine-tune the details of the trial of Russian officials is at the end of wide-scale hostilities and the transformation of the war into a post-conflict political settlement. It is the military outcome of the war that will establish steady grounds for the peace negotiations. Moreover, it can create very different negotiation options, including those that require compromises as well as certain package deals. Having the idea of a trial for the Russian officials that is universally accepted and supported will certainly be an advantage for the negotiations. Practical implementation of this idea will depend on many factors; persistence and coordination of diplomatic efforts will be among the key ones.

The example of the crashed and occupied Germany of 1945 demonstrates a wider set of options available to the winners. If Ukraine’s victory is not that overwhelming, international sanctions will become another critical factor to ensure from Russia the level of cooperation needed to establish the tribunal. This implies prolonged unified pressure from the international community while simultaneously keeping open the option of the trial of high-ranking Russian officials as part of a package deal. This well-known pattern turned out to be successful in several different cases. A particular example was the isolation of South Africa for its policy of apartheid. That strategy finally achieved its goal with the end of apartheid in the early 1990s.

Example: Timeline for International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY)

1992 – Radovan Karadzic was elected as the President of Republika Srpska (part of Bosnia and Herzegovina).

1993 – International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was formally established following the approval of the UN Security Council resolution # 827 of 25 May 1993.

1994 – ICTY work officially begins.

1995 – First reported war crimes by Karadzic.

1995 – Karadzic was formally indicted by the ICTY

2008 – Daradzic was arrested in Belgrade

2010 – The prosecution of Karadzic began

2012 – The prosecution of Karadzic completed

2012 – Karadzic defense began.

2014 – Defense of Karadzic was completed

2016 – Karadzic was found guilty of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 40 years imprisonment

2016 – Appeal was filed

2018 – Appeal hearings took place

2018 – The composition of the appeal chamber was changed.

2019 – The appeal judgment was proclaimed, sentencing Karadzic to life in prison.

The formalization of the terms and conditions of the trial of Russian officials can have unilateral, bilateral, or multilateral basis. In terms of unilateral or bilateral options, the legal aspects are rather straightforward: Russia, by its sovereign, will transfer its citizens accused of international crimes to the jurisdiction of the selected court. The example of postwar Japan of 1945 demonstrates that this scenario is certainly possible.

Unilateral. Separate from other documents that finalize the war, Russia can issue a unilateral declaration of its option for the trial of its officials based on either national or international jurisdiction.

Bilateral. A selected option for the trial of Russian officials can be included in Russia’s instrument of surrender or its bilateral peace treaty with Ukraine. Although in full compliance with international law, this scenario is rather problematic from a political perspective, as it requires both an evident military defeat of Russia and the acceptance of this defeat by Russia’s political elite. Either of these conditions alone is difficult to reach in reality, let alone both. The Russian society and political elite can hardly accept a military defeat without the occupation of the territory of Russia, a scenario that is next to impossible. Neither will it be easy for Russian society to accept the fact that the war with Ukraine has been lost. From a wider perspective, a bilateral peace treaty between Russia and Ukraine is not the best solution either, as it will have limited character, which does not correspond to the nature of this war initiated by Putin against NATO and the “collective West.” A long-lasting peace in Europe is hardly possible without a serious transformation of the entire security architecture in Europe supported by steady international implementation mechanisms. Certainly, the end of the war in Ukraine appeals for such reforms should come after the war to prevent history from repeating.

Multilateral. The ultimate decision as to the trial of Russian officials can be adopted by an international conference/congress organized to reestablish peace in Europe. This mechanism has been widely used to rearrange international relations during critical periods of history. Typically, international conferences (congresses) were organized after significant military conflicts that had resulted in multi-faceted complex consequences for Europe or the world in order to determine the postwar status quo.

Such a mechanism can be legitimately utilized to formally end the Russian war in Ukraine. The conference (congress) can be arranged under the aegis of the UN or separate regional European organizations (OSCE, Council of Europe) or under a wider aegis including all of them (as well as the European Union), thus enhancing the common accord as well as the legitimacy of its decisions. It should also be noted that the offered format of an international treaty a priopi implies the need for ratification by Russia due to the principle of pacta tertiis nec nocent nec prosunt, i.e., the quality (limits) of the treaties to create rights and obligations only for those who are the parties of this treaty. International conferences were successfully used as a legitimate mechanism to establish first-generation tribunals.

There is nothing that prevents making the decisions of the conference compulsory for Russia a priori either via the rules of procedure or by referring to the wide international status of the conference. It is up to the conference to select a preferred option for the trial of Russian officials. From a legal perspective, Russia’s agreement to participate will mean its acknowledgment of the compulsory nature of the conference’s decisions. Russia’s refusal to accept the decisions of such a conference would mean the need to force their implementation by continuing the international pressure on Russia, which will yield results sooner or later. From the political perspective, the implementation of the formal decision of such a conference (congress) will be better accepted by Russian society for at least two reasons. First, it will not be directly recognized as the surrender to Ukraine, but rather to the “collective West.” And second, the trial of high-ranking Russian officials will be viewed as part of a package deal that implies the simultaneous resolution of a number of other sensitive political issues.

Conclusions and recommendations

“Anybody” is the answer to the question posed in the title of this paper. A wide range of courts can judge high-ranking Russian officials, including Putin, for their crimes in Ukraine. This range includes the ICC, any ad hoc tribunal created under different aegis, as well as the national courts of Russia, Ukraine, or a third country. Because of the wide-scale, flagrant nature, and brutality of Russian atrocities in Ukraine, the idea of holding Russian officials accountable for international crimes is widely accepted and supported. However, to transform this idea into reality, there are two components that should be in place: political will and skillful diplomacy.

From a practical perspective, the following issues require attention from policymakers, international law practitioners, and human rights organizations:

- The ongoing practice of collecting and documenting Russian crimes in Ukraine by both national and international forensic institutions, investigators, etc. is important. Publication of these materials is already an important factor influencing global public opinion, thus creating support for the punishment of high-ranking Russian officials for their atrocities in Ukraine.

- The establishment of the International Centre for the Prosecution of the Crime of Aggression Against Ukraine at Eurojust both reiterates the international commitment to ensuring full accountability of Russia and indicates the formal involvement of the European Union in the process.

- Due to the nature of contemporary international relations, the actual outcome of the war may have a certain influence on the format of the prosecution of the Russian officials. Besides establishing steady grounds for peace negotiations, it may also create very different negotiation options, including those that require compromises as well as certain package deals.

- From a practical perspective, the best time to fine-tune the details of the trial of high-ranking Russian officials is at the end of wide-scale hostilities and the transformation of the war into a post-conflict political settlement — i.e., after diplomacy returns to action.

- With the existing support for the idea of holding Russian officials accountable for their crimes in Ukraine and certain frictions as to the particularities, the continuation of diplomatic consultations with the ultimate goal of achieving a unified approach is of importance.

- A diverse range of options exist, including inter alia a wider involvement of the ICC as well as national jurisdictions to try Russian officials for crimes committed during the course of the war in Ukraine. Without prejudice to the possibility of establishing any ad hoc tribunal, the world already has a judicial machinery to punish Russian officials accused of war crimes. Thus, bringing Putin and his administration to justice is an issue that is more from the realm of diplomacy than that of law.

- There is a need to ensure a certain level of cooperation from Russia, at least for the extradition of the accused. Thus, the persistence and coordination of diplomatic efforts are key factors in the continuation of international pressure until such cooperation is achieved.

- Attention should be paid to the historical experience of international conferences (congresses) being legitimate mechanisms for establishing both the postwar status quo and solid legal foundations for international criminal proceedings.

- Independently of the format selected for the prosecution of Russian officials, it is important to ensure unified proceedings — either by establishing a common chamber or by having a single trial in front of different courts, which would then make a unified decision, with each ruling within the limits of its jurisdiction.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.