Melissa Bell loves to paint images of water. In her work, blues and greens swim alongside one another in a colourful flow. “I grew up on the river in the backyard,” the artist says. “I was pretty lucky with that, living on country at Cummeragunja on Yorta Yorta, where I’m from. The water was always a part of me.”

Bell always loved art – and studied it at RMIT – but then her life got “a bit chaotic”. “I ended up meeting a partner, [which led to] domestic violence, and I lost my way,” she says. Bell was incarcerated for the first time in 2015 when she was in her late 20s, and four more times over the next five years.

It was in prison that she began painting again, in a program run by the Torch: an organisation that engages incarcerated Indigenous Australians in art. Run across all Victorian correctional facilities, the program helps participants connect with their language and culture through art workshops, and showcases their work in an annual exhibition. The program also provides ongoing support post-release, including connecting participants with artist networks and institutions. Some of the program’s artists have had work acquired by major galleries, including the National Gallery of Victoria.

“There were a few times I went in and out [of prison] but the very last time, I got really connected with my painting,” Bell says. “I was really excited the last time I came out of prison … I couldn’t wait to create artwork.”

Bell’s work is part of the Torch’s most ambitious show yet: Blak In-Justice, presented in partnership with Heide Museum of Modern Art – marking that gallery’s first Indigenous-led exhibition.

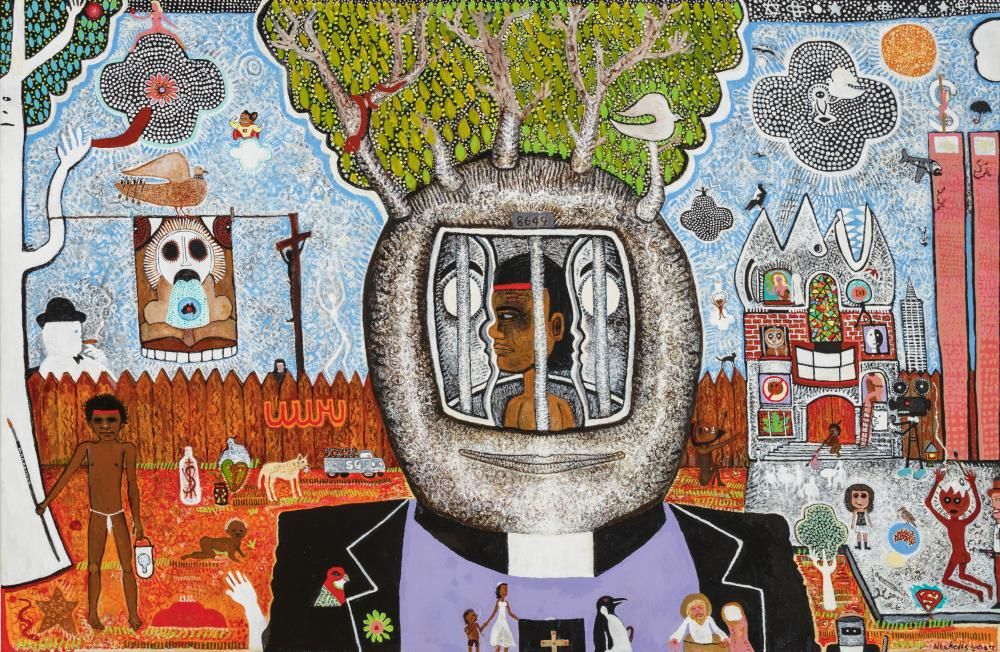

Blak In-Justice showcases work from some of the Torch program’s participants alongside leading First Nations artists including Judy Watson, Vernon Ah Kee and Destiny Deacon, as well as frontrunners such as the late Albert Namatjira.

Indigenous Australians represent less than 4% of the total population but account for 36% of the prison population. Of all those aged between 14 and 17 in youth detention, 64% are First Nations. Indigenous men are 17 times more likely to be incarcerated than their non-Indigenous counterparts – and for women, that rises to 25 times more likely. Since the 1991 royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody, close to 600 Indigenous Australians have died within the system.

In her installation blood and tears, the Waanyi artist Judy Watson inscribes some of those people’s names on to red welding curtains with braille, the marks puncturing the material so that light shines onto the wall behind – “like bullet holes, awash with blood and grief,” in her words. A striking stained-glass triptych from the acclaimed Girramay, Yidinji and Kuku-Yalanji artist Tony Albert shows three men with targets on their chests. The Kamilaroi artist Reko Rennie’s painting Three Little Pigs, which debuted in his NGV survey show in 2024, is also on display; a bold statement about police brutality.

These works sit alongside pieces by artists who have been through the program, from Bell’s depiction of the Murray River to the Darug artist Daniel Church’s wood-carved pelicans, and the Yorta Yorta artist C Harrison’s painting Deaths in Custody, which illustrates, with 440 identical figures, the number of deaths at the time it was painted in 2021.

Taken together, the works constitute a polyphonic, multidisciplinary exhibition – a choir of diverse artists singing out together.

“I wanted to bring together the extraordinary voices of those that hadn’t been incarcerated … and the journeys [of those who have been imprisoned] to free themselves from that system through connection to art, culture and country,” says the Barkindji artist and curator Kent Morris, the creative director of the Torch. “Put them all together, all this mob … it’s something that cannot be ignored.”

There’s a “crossover group” within the show, too: the revered Walmatjarri artist Jimmy Pike started his career while incarcerated in Fremantle prison, the Wiradjuri artist Kevin Gilbert began making his distinctive linocut prints in the New South Wales prison system, and Namatjira – one of the most renowned Indigenous Australian artists – was briefly incarcerated near the end of his life.

The government’s Closing the Gap initiative was launched in 2007 to address the inequity of Indigenous incarceration. Morris is straightforward: “It’s clearly not working.”

On its own, the Torch can’t change the ingrained institutional biases but it has had a positive impact on participants – more than 800 of them since its inception in 2011. A study of 75 participants showed that the recidivism rate was 11% for those who stayed connected to the program for a year post-release, reducing to 9% for those who stayed connected for two years. This is in comparison to the average recidivism rate of 55% for Indigenous people in Victorian prisons, and 76% nationally.

The program also resulted in the Victorian government’s Aboriginal art policy model, introduced in 2016, which allows participants to sell their artworks while still in custody and receive 100% of the proceeds. Morris explains that this “empower[s] some economic independence and the opportunity to make different decisions through self-determination”.

“It changed my whole life,” Bell says of the program. After being released from prison for the final time in 2020, she began working for the Torch in a support role and now works in the construction industry while continuing her art practice. “I can’t believe it, where I am,” she says. “If it wouldn’t have been for the Torch, I wouldn’t be here … opening them doors for me and connecting back with my culture and family.”

The Torch’s impact relies on the involvement of non-Indigenous Australians, too. “First Nations communities already have developed solutions and ways to resolve this and to make significant positive impacts but we’re just not getting the level of support needed to really turn it around,” Morris says. “What this exhibition says is: we can do the heavy lifting and the hard yards but we need your support.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.