In a small conference room nestled inside a secure red-brick building, I met with 11 fellow staff members of the Nash News, a prison newspaper in North Carolina. It was late March, and we were huddled over folding tables to discuss a novel idea: hosting a mock election for Nash Correctional’s 900 medium-custody prisoners.

Cris, the paper’s graphic designer, suggested it. “Maybe we can learn how our choices compare with society’s,” he said, smiling. “It’ll make a helluva story, too.”

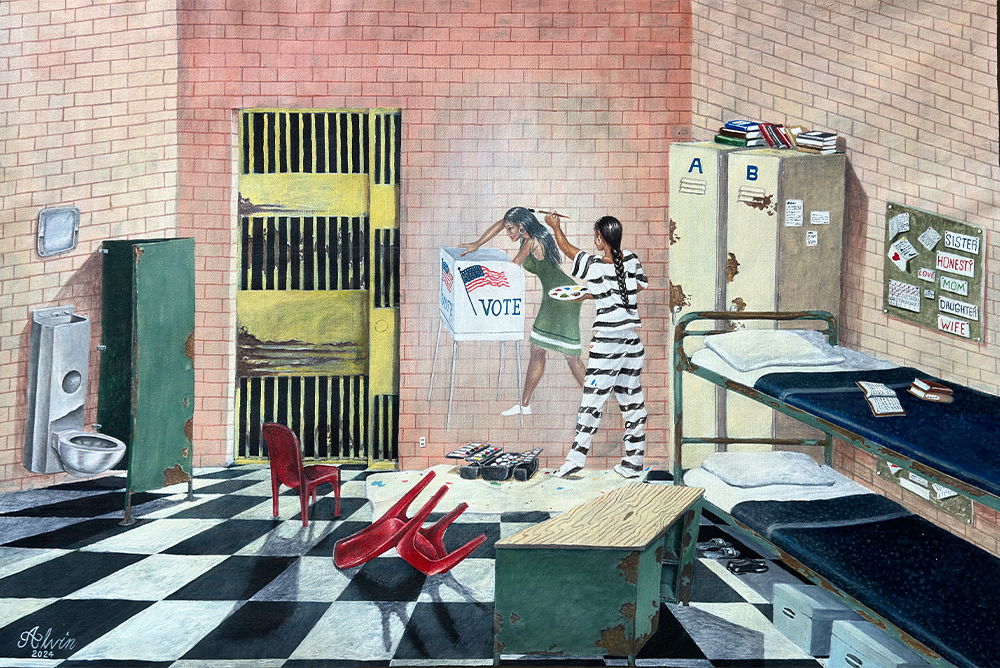

A news story felt secondary, I thought, but a mock election would spark interest. It could also be transformative for men who will regain voting rights upon completing their sentences, modeling a democratic process they’ll eventually be able to participate in themselves.

We couldn’t do it just because we wanted to. First, we needed prison approval, which depended on logistical criteria: Is the gym available? Is there sufficient staff to supervise? But the larger question was a philosophical one: Would the prison see merit in our idea?

“To get approval,” I said, “we’ll have to explain why elections are important to a class of felons that can’t legally vote.”

Cris picked up his pen to jot down our ideas.

Incarcerated people care about elections because they can give us either hope or hopelessness. Criminal disenfranchisement, which traces its roots back to ancient Greece and Rome, is a sterile term for the irreconcilable truth that one of the groups most affected by elections cannot vote in them.

The decisions elected officials make shape nearly every aspect of our lives inside—from the quality of the food we eat to the length of the sentences we serve. The U.S. president and state governors can grant clemency; appoint prosecutors, law enforcement, and prison officials; and nominate judges who oversee criminal trials and appeals. Sometimes those judges, prosecutors, and sheriffs themselves show up on the ballot. Legislators, meanwhile, pass criminal codes and budgets governing prison conditions. I’ve witnessed enough elections from behind bars to understand their importance.

I was sentenced to life without parole for murder in 2002. A year earlier, while in jail awaiting trial, I awoke to images of airplanes smashing into the World Trade Center on 9/11. I was 23 and did not yet understand the politics of tragedy. Over the next few years, I watched that horrifying event propel George W. Bush to a second term in 2004. That’s when I started paying attention.

Shortly after the next election I folded t-shirts in a prison clothes warehouse during Barack Obama’s first inauguration in January 2009. A white female guard working beside me smiled up at the TV mounted in a steel cage on the wall. “I’m so proud of America,” she said, wiping tears, “and I’m not even Black.”

Hope is not a solid structure in prison. It gets torn down, and reconstructed.

The same election installed Beverly Perdue as North Carolina’s governor. Shortly after, the legislature passed a budget, signed by Perdue, which slashed prison resources. We lost access to decent health care, quality hygiene products for indigent prisoners, and real chicken and beef in the chow hall (replaced by processed meat patties). Several smaller prisons closed, and thousands of state employees endured furloughs or pay cuts. Many correctional officers resigned or lost their jobs, leaving prisons dangerously understaffed. I got my first real lesson in how dramatically the decisions of politicians outside prison can reshape life inside.

In 2016, the Clinton-Trump election brought a new lesson, showing me how divided America had become. Acidic campaign ads were shoved between laundry detergent and nacho chip commercials during NFL games. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan resembled a Confederate war cry.

This division wasn’t just something we watched on TV. On the rec yard one day, I saw a white guard speed past the prison in his truck, honking to make sure we saw his huge Trump flag flapping. White prisoners pumped their fists and yelled in solidarity. A Black guard stood on the yard watching. “I gotta vote for Hillary,” he said, sighing.

When my mom, a Black woman from Chicago, came to visit, we agreed that Trump had emboldened white supremacists. But I also had monthly visits from my friend Bill, an elderly white Catholic and a Trump supporter. In his complaints about immigration and the economy, I recognized a feeling of vulnerability that Trumpian rhetoric exploited. People like Bill idolized Trump in the same way that I once idolized Obama, a Black man who experienced the same racial harms I had. I thought of Obama as someone fighting to make things right for me. I imagined Bill thought the same of Trump.

Bill was elated when Trump won. I was horrified.

Four years later, I followed the 2020 election with Bryce, a good friend who had majored in political science before landing in prison. “When politicians talk about money and prisons,” he said, “pay attention.”

Last year, the United States spent some $182 billion to imprison 1.9 million people. North Carolina spends about $133 per day—or $931 per week—to house each person incarcerated in the state, a figure that rose about 40% between 2021 and 2023. The most recent median weekly earnings for a full-time worker in the United States totaled $1,143. If the cost of incarceration continues to grow, North Carolina could eventually find itself paying more daily to house a prisoner than its free citizens earn for a hard day’s work.

In 2020, I remember watching a Biden-Trump debate with Bryce when Biden laid out a plan to end mandatory minimum sentencing by offering financial incentives to states—a stark contrast to the ’90s-era legislation he sponsored to enact harsher criminal sentences. I had never felt more hopeful. Maybe one day, I thought, I could walk out of prison.

Biden later abandoned his plan, making me wonder why I had been so hopeful in the first place. But hope is not a solid structure in prison. It gets torn down, and reconstructed. People on the inside continue trying to make a difference.

That same year, I coauthored a reform bill with Timothy Johnson, an incarcerated friend: the Prison Resources Repurposing Act, or PRRA, which aims to extend release to some serving life without parole if they can achieve educational, vocational, and behavioral goals. Democrats in the North Carolina House of Representatives sponsored the PRRA in 2021 and 2023, but it never came to a vote.

Until recently, I followed this year’s election with dejection. I found the most recent Trump-Biden debate pitiful, and I stopped watching halfway through, wishing both sides had better choices. But when Vice President Kamala Harris stepped in, she breathed new life into a dead contest. While I don’t affiliate with either party, if I could vote, I would vote Democrat, because we need to balance the Supreme Court, which is supposed to act as an impartial fulcrum. I worry about the partisanship that weighs down the current court, which governs criminal justice issues including fairness in criminal sentencing and prison conditions.

Inside, people boast about who they support. Many like Trump because he’s a so-called outlaw. Some don’t think Harris can win because she’s a Black woman. I’m doing time with a Black Republican who holds religious, conservative values and doesn’t seem to care that the party’s “tough-on-crime” stance offers no leniency for his life-without-parole sentence. Many others don’t pay much attention to the election at all, probably because it still feels disconnected from their realities.

Shortly after our Nash News meeting, Cris submitted our proposal, and the mock election was approved. We hope to hold it a week before election day and to pass out ballots featuring candidates for president, governor, and state attorney general. We plan to include a questionnaire on the back of the ballot inquiring about age, political affiliation, and other demographic traits. We’ll tally the results and share them on our prison-issued tablets.

Then, on Nov. 5, I’ll sit by the unit TV to watch the real-world returns with Bryce. We’ll talk politics over sodas and burritos, and compare how our prison’s results match up with voters in the free world. The whole time, I’ll watch with hope for democracy—inside and outside our prison. The results will offer hope or hopelessness for us all.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.