David Muhammad’s middle school in Oakland, Calif., labeled him “gifted and talented,” but classes bored him. The streets were more appealing, and by ninth grade he had found a group of friends to skip school and sell drugs with. He remembers it as easy money: “There were a lot of people who wanted drugs in East Oakland and South Berkeley in the 1980s and early 1990s. As long as you avoided joining a crew or getting involved in neighborhood beefs, you could make money without much violence.”

Listen to this article, read by Prentice Onayemi

Muhammad’s parents had little to say about how he spent his days. The couple met while registering voters in Georgia in the 1960s, but they were never as passionate about parenting as they had been about civil rights. When Muhammad was 3, his parents split up, and he was raised in a household with his mother and two older brothers. When he was 15, his mother moved to Philadelphia with her boyfriend, leaving Muhammad in the care of his brothers, ages 20 and 21, both of whom were involved in Oakland’s drug scene.

This worked out pretty much the way you would expect. Over the next two years, Muhammad says, he was arrested three times — for selling drugs, attempted murder and illegal gun possession. The first two cases were dismissed; he received probation for the gun charge. “We’ve seen this story too many times,” Muhammad reflects. “A Black kid from Oakland with absentee parents and a juvenile record. It’s not supposed to end well, right?”

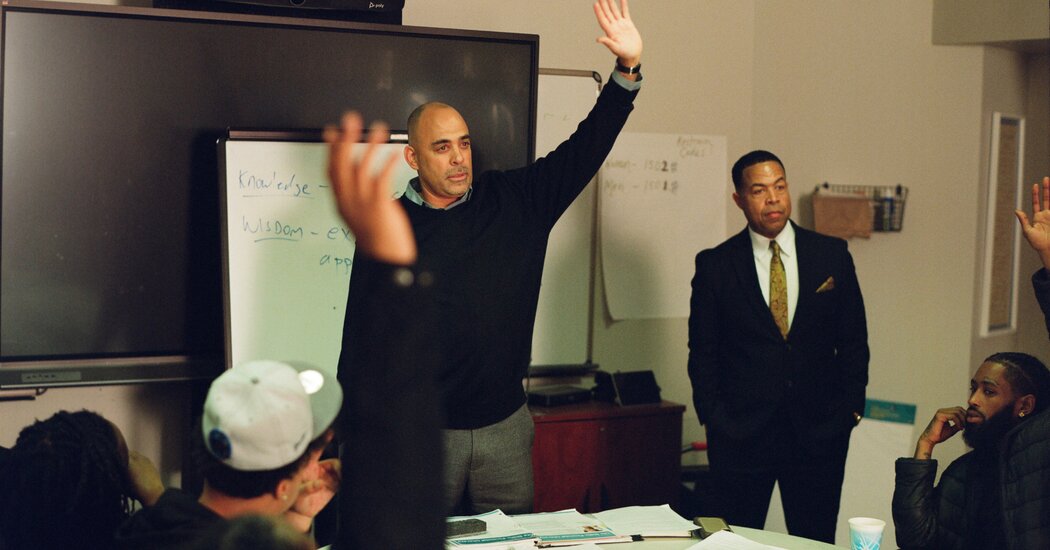

But for Muhammad, it did. He wound up graduating from Howard University, running a nonprofit in Oakland called the Mentoring Center and serving in the leadership of the District of Columbia’s Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services. Then he returned to Oakland for a two-year stint as chief probation officer for Alameda County, in the same system that once supervised him. As Muhammad says: “I went from being on probation to the head of probation. And I went from being locked up on the second floor to a corner office on the fourth floor.”

Muhammad’s unlikely elevation came during a remarkable — if largely overlooked — era in the history of America’s juvenile justice system. Between 2000 and 2020, the number of young people incarcerated in the United States declined by an astonishing 77 percent.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.