Last week, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) presented one of its most politically significant indictments in six years of investigations and the most symbolic so far against a state agent in Colombia. It accused retired General Mario Montoya of having committed war crimes and crimes against humanity, the two most internationally reproached crimes, for his role as head of a Colombian army brigade that committed 130 extrajudicial executions between 2002 and 2003.

The special tribunal stemming from the 2016 peace agreement had already indicted two generals and 14 colonels for the murder of civilians who were then falsely presented as Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN) rebels killed in combat, a crime known to Colombians by the euphemism ‘false positives’. But none had the public profile of Montoya, who became commander of the Army and member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the Armed Forces between 2006 and 2008, coinciding with the peak of these crimes.

“Mario Montoya adopted a de facto policy in the Fourth Brigade that prioritised deaths as the only real indicator of military success. He required, demanded, pressured, compared and measured all troops under his command” according to this parameter, said justice Catalina Díaz, who led the investigation that also accused two colonels and six other military officers in the north-western department of Antioquia.

“He was aware of what he was doing”

Although the JEP did not accuse the general of committing any of these murders personally, it held him accountable for the crimes perpetrated by members of the six military units under his command. “All of these murders were committed with the ultimate aim of responding to the pressure for ‘casualties’ and ‘litres of blood’ exerted by General Mario Montoya,” the indictment states. “This is not an accidental repetition, nor were they isolated or unconnected events.” One unit, the 4th Artillery Battalion Colonel Jorge Eduardo Sánchez, was responsible for over a hundred crimes.

The special tribunal documented four reprehensible actions by Montoya. First, he pressured his subordinates to produce combat kills at all costs. Second, he ordered his men not to report captured or defecting rebels, regarding casualties as the only valid indicator of mission accomplishment. Third, he used notoriously violent language that incited the unlawful production of combat deaths. Finally, he lied about how these alleged casualties occurred and even covered up overreach by his men. For this reason, the JEP charged him with the war crime of wilful killing of protected persons and the crimes against humanity of homicide and enforced disappearance.

With this behaviour, the JEP established, Montoya “created the conditions conducive to the emergence of the macro-criminal pattern” and “influenced security forces members under his command, instigating the perpetration of crimes”. The effect of his conduct was, according to the indictment, to “generate a permanent situation of risk for the civilian population that he himself was called upon to protect as institutional guarantor”. In fact, the special tribunal says, it found no soldier who had heard clear messages from him about the duty to protect civilians not taking part in hostilities. He was, says the JEP, “aware of what he was doing”.

In addition, the JEP established that the eastern region of Antioquia where these units operated – immersed at the time in an intense armed confrontation – became a kind of laboratory where this criminal pattern took shape and from where it spread to the rest of the country. “What happened in Antioquia was a determining factor in the national dynamics of the phenomenon,” it said.

A fifth indictment but one same pattern

In this fifth indictment, the JEP details behaviours that it had already identified in previous accusations, providing new examples to illustrate the criminal pattern of murdering innocent civilians and falsely passing them off as rebels killed in combat. For example, it details the methods used by Fourth Brigade to profile and select victims, mostly poor peasants taken from their farms and singled out without proof of being rebels or their sympathisers, on what the JEP called “the premise that their forced coexistence with the guerrillas was an unequivocal sign of loyalty to them”. Through this stigma, the special tribunal argues, the military justified their crimes.

The JEP magistrates also found in this region the seed of what would trigger scandal five years later: how many military officials lured people from other cities with fake employment promises and then killed them, choosing them because they were unemployed, had disabilities or problematic drug use, on the assumption that this reduced the likelihood that they would be searched for. In one particularly vicious episode, it recounts how soldiers in civilian clothes parked a van at a Medellín marketplace and recruited four day workers for a supposed housing move, instead driving them to a village in Granada – 80 kilometres away – where they were murdered and buried in a mass grave. The JEP also documented how soldiers under Montoya’s command killed 14 guerrillas who’d been captured or surrendered and were therefore out of combat according to international humanitarian law, including an invalid man at a FARC field hospital.

Similarly, the indictment documents how many of these murders were carried out in collusion with right-wing paramilitaries to the point that several victims reported having seen them changing armbands or patrolling together. Or how they planned and covered up crimes by forging operational documents and coordinating accounts before the justice system investigating them.

“The only real indicator of military success”

Perhaps the novelest aspect of the indictment against Montoya and the other members of the Fourth Brigade is that, rather than exhaustively describing its 130 extrajudicial executions, the special tribunal focuses on detailing the mechanisms that allowed them to occur and how commanders instigated them.

According to the JEP, military units in eastern Antioquia between 2002 and 2003 had a single mission: to produce as many guerrilla deaths as possible. For Montoya, other indicators of success in the counterinsurgency war – such as capturing enemy troops or encouraging them to voluntarily defect – had no value and were discouraged. Producing casualties was “the only real indicator of military success”.

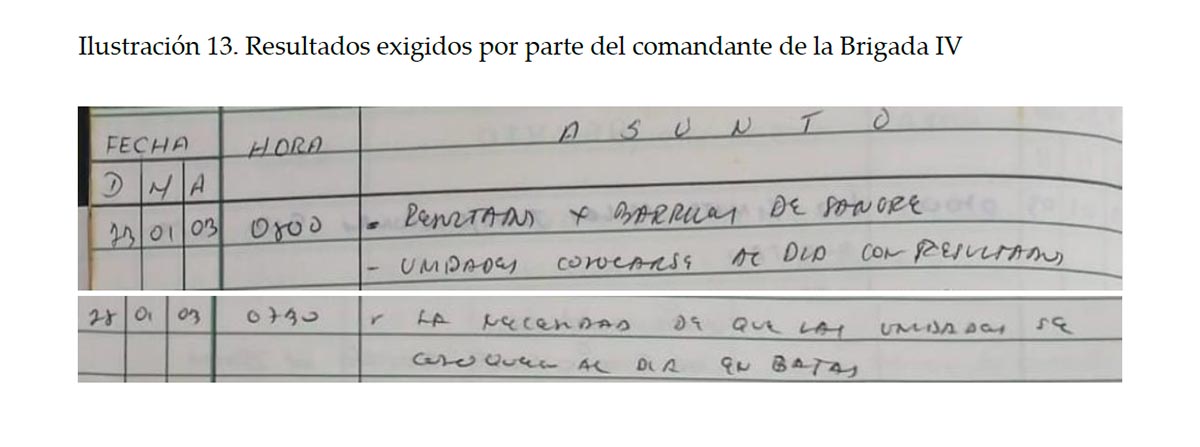

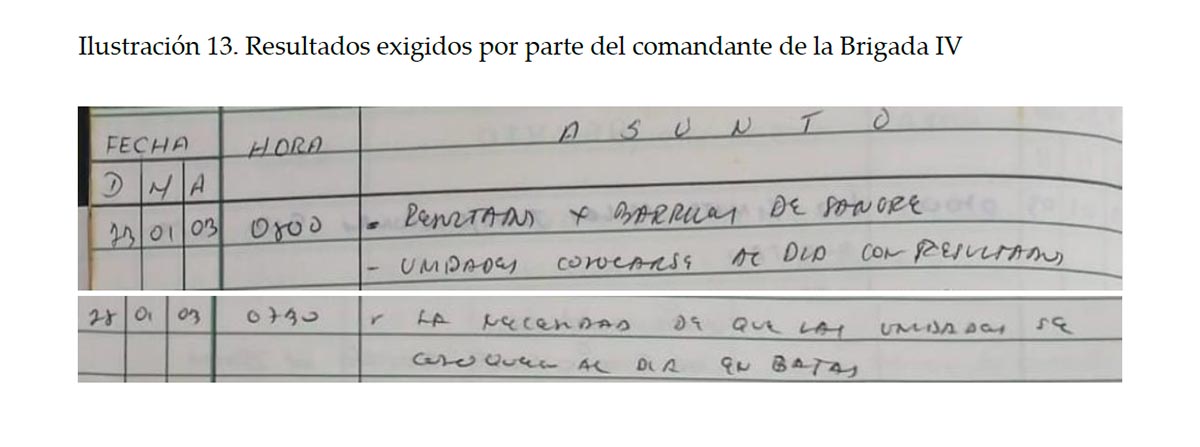

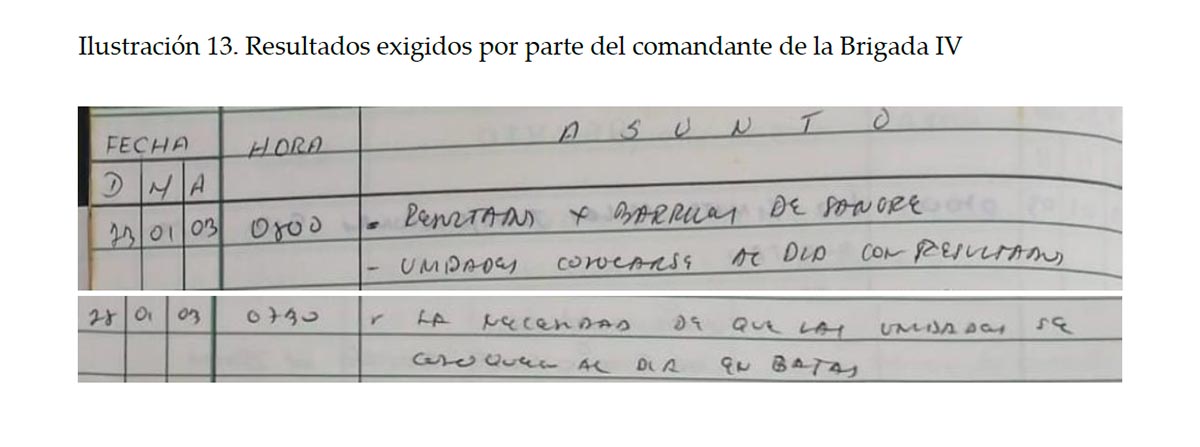

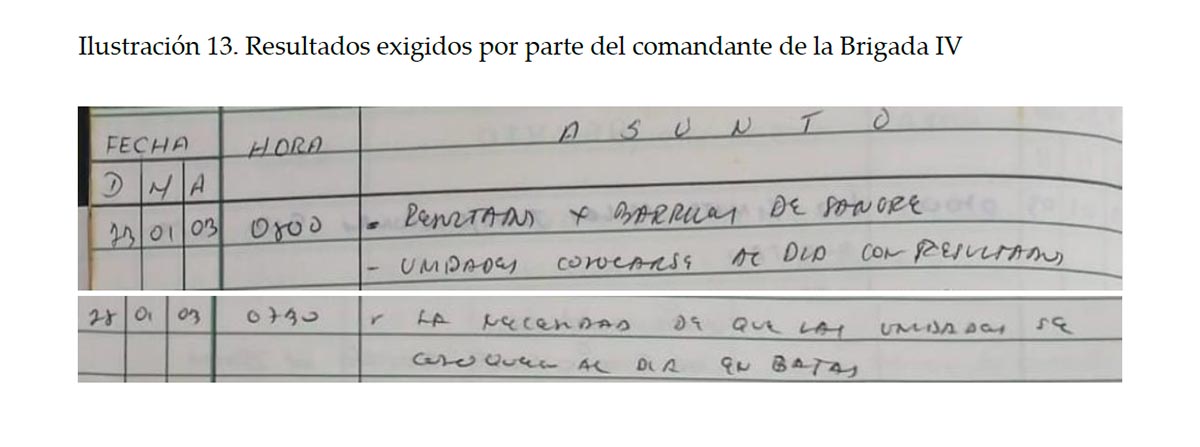

It was a message Montoya hammered home in his weekly radio addresses to troops and in interactions with his subordinates, which were then echoed by his battalion commanders and went down the chain of command. In these speeches, Montoya stressed the “need for units to catch up with casualties”, encouraged them with exhortations such as “the best brigade is the one that gives more than 204 [casualties], we have to be the best” and, when there were none, pulled their ears by telling them that “manpower is not on par with operational results”, as reconstructed by the JEP through dozens of military testimonies and official transcripts in military archives.

At the same time, Montoya discouraged any reporting of different achievements, encouraged competition between units and established rankings by number of casualties. “Don’t give me faggotries, defections, surrenders, wounded or bullshit. What I want to see is blood,” a corporal reportedly heard him say. His behaviour was emulated by his commanders, as another dialogue recounted by a lieutenant shows. “I have two captures,” a soldier reported. “How many casualties?” his superior replied. “No, two captures,” he clarified. “How many casualties?” came the reply again. “No yes, two, two,” corrected the soldier. “Ah good, excellent,” he complimented him.

This constant pressure led the military to internalise that, in one corporal’s words, “the result could not be less than a casualty”. For this reason, the JEP concluded that this pressure for casualties was “the starting point” of the criminal pattern.

Rewards for casualties, punishments for not giving them

One factor that contributed to instilling this pressure among Fourth Brigade soldiers was an incentive system rewarding those who produced casualties and punishing those who didn’t.

Those reporting the most combat casualties, either individually or as a group, received medals, cash bonuses, public praise, congratulations on their CVs that were useful for promotion, aviation course recommendations, patrol shifts in quiet villages, paid trips to the Caribbean and commissions to the Multinational Peace Force in the Sinai Peninsula. The most sought after by soldiers were the five days of leave that they received for each casualty and could accumulate, in what the JEP called an “arbitrary handling” that took advantage that this wasn’t regulated. It was so effective that they even adopted it as a metonymy. “See, that’s five days walking there,” one soldier said. On the other hand, those who didn’t produce casualties received public humiliations, annotations on their résumé for “lack of work competence” and transfers to more violent and isolated regions of the country.

The measuring stick, according to the tribunal, was always how many deaths they’d achieved. “If you had many, you were good; if you had few, you were asleep; if you had none, you were bad and useless,” said one corporal. The JEP documented 24 radio programmes where Montoya congratulated those who’d produced casualties, but not those who made captures or weapons seizures.

These incentives had a significant impact on recipients’ careers. While Colonel Iván Darío Pineda, also an indictee, was sent to the Chilean Artillery School as a teacher and later appointed director of the Colombian one, others saw General Montoya use his discretionary power to force their departure from the army or transfer them.

“Bring me litres of blood”

General Montoya’s language, according to the JEP, “incited the indiscriminate use of lethal force”. His interactions with subordinates were full of allusions to “litres”, “jets”, “rivers”, “barrels” or “truckloads of blood”, as several military officials testified. “Don’t bring me problems, bring me litres of blood”, a sergeant overheard him say. On his orders, they even had to report themselves saying “no news or litres of blood reported”, repeating the salute if they omitted the last part, another sergeant said. This bloody leitmotif was, according to the JEP, what “had the greatest effect (…) in internalising the message that combat casualties were the only indicator of success”.

In addition to the continuous references to blood, there was another linguistic peculiarity: ambiguous orders that did not indicate the purpose to be served on a detainee but were sufficiently suggestive, such as “you know what you have to do”. A captain told the JEP that on one occasion he reported a casualty and two rifles, to which his commander replied: “You have one killed in combat and you have one rifle, look for the owner of the other rifle”. When a sergeant reported finding an invalid guerrilla in a wheelchair, one of his colleagues said that the response of his superior, Colonel Julio Alberto Novoa, who is also accused, was “No, well, then I’ll send the inspector there to do the search”. This was a veiled allusion to the forensic officer who processes the bodies on a battlefield.

For the special tribunal, these were “implicit messages that led to the killing of persons then presented as combat casualties”, expressed in language contrary to a military commander’s duty of giving clear orders.

Cover-up in San Rafael

One of the JEP’s harshest accusations against Montoya is that he lied about the unlawful nature of many of these casualties and even covered up excesses by the men under his watch. It does so recounting a specific episode: on 9 March 2002, soldiers shot at a pick-up truck in a rural area of San Rafael where a paramilitary known as ‘Parmenio’ was travelling, without realising that five civilians were inside and also killed on the spot. Among them were a 13-year-old and a 16-year-old girl, who had asked for a ride to a party because there was no public transport. The soldier reported the civilian deaths to his commander, Colonel Novoa, who in turn informed Montoya.

“We have to say that those killed are rebels from FARC’s Ninth Front,” Montoya reportedly said upon arriving the following day by helicopter. Novoa tried to correct his mistake but the general ordered him, in the JEP’s words, to “sustain and publicly communicate this false version of facts”. He himself called a press conference at the elderly hospice and publicly identified them as guerrillas. He never mentioned that they were civilians, as his subordinates warned him, or that two were children. “You’ll need your whole life – and I’ll have ample time – to prove that my daughter was a rebel!”, Gloria Lucía López, mother of 13-year-old Érika Viviana Castañeda, scolded him.

“This conduct by the commander sent a message to his subordinates that it was acceptable to lie when showing results in the fight against subversive groups and to cover up a possible irregularity,” the JEP concluded.

Montoya’s (and his political defenders’) dilemma

General Montoya, who has so far denied responsibility, will now have six weeks to decide whether to accept the JEP’s charges.

Under the transitional justice’s two-track system, he and the other eight new indictees may receive a more lenient 5-to-8-year sentence in a non-prison setting if – and only if – they meet three conditions: acknowledging their responsibility, telling victims’ families the truths they still yearn for, and personally redressing them. Most defendants have so far chosen this route: 55 of the 62 military officials accused in this macro-case have owned up to their crimes. The remaining seven will go to an adversarial route and, if convicted, face 15-to-20-year prison sentences. A month ago, the JEP prosecutor’s office filed charges against the first of these, Colonel Hernán Mejía.

The political sectors that have staunchly defended Montoya also face a dilemma: whether to accept the evidence of a JEP they’ve so far been sceptical of and the confessions of the implicated soldiers themselves. Former President Álvaro Uribe, who appointed Montoya as the Army’s top commander and later as ambassador in the Dominican Republic, defended him until three years ago as “a national hero” and warned of an “injustice” against him. After the indictment, he defended his security policy and his corrective measures after learning of the extrajudicial executions and again attacked the transitional tribunal as “a FARC imposition”, but admitted that “some members of the Armed Forces, in order to show off, violated human rights and committed false positives”. He didn’t name Montoya, who resigned from the army in 2008 just as Uribe took corrective measures.

Uribe’s acknowledgement of this macabre reality, even if only partially, shows that after years of divisions on the issue, Colombians are closer to recognising that – as the JEP says – many in the military believed that “the way to fulfil their constitutional duty was to kill at all costs and display corpses”.

Recommended reading

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.