In a digital age where social media reigns supreme, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) has ventured into uncharted territory: TikTok. Yes, you read that right. This international court, tasked with addressing the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge regime, has taken to a platform known for dance videos and viral trends to engage with Cambodia’s young population as it works toward accountability for one of the most harrowing chapters of the 20th century. As the first international tribunal to use such a seemingly unconventional platform, the ECCC is pioneering a new era of how these tribunals can connect with the public.

Residual functions at the ECCC

The ECCC was established by an agreement between the UN and the Royal Government of Cambodia, formalised in 2003. The ECCC was created to prosecute the senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime as a “hybrid” court, combining Cambodian and international judges, aspiring for both local legitimacy and adherence to international standards.

The Court convicted three senior Khmer Rouge leaders: Kaing Guek Eav, alias “Comrade Duch,” head of Tuol Sleng prison (S-21) (sentenced 2010), and senior leaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan (convicted in 2014 and 2018, respectively). Key figures like Pol Pot never faced trial, as he died in 1998. Similarly, Ieng Sary, former Minister of Foreign Affairs, and his wife Ieng Thirith, who were indicted, were never convicted due to their deaths during the proceedings. In 2023, the ECCC entered a three-year residual phase following the appeal judgment in Case 002/02, marking the end of its judicial process and the beginning of its residual functions. In certain international criminal tribunals, the residual phase covers functions such as public outreach, sentence enforcement, records management, and other responsibilities that take place after the core judicial proceedings have ended.

With extensive academic and media coverage during high-profile trials, the commencement of the residual mandate has seen a significant decline in coverage of the ECCC.

Following an agreement between the UN and Cambodia, the ECCC’s residual functions – guided by the Report by Co-Rapporteurs on Residual Functions Related to Victims – focus on several key areas: capacity building with local institutions, victim support initiatives, national reconciliation, sentence enforcement and information dissemination. The residual phase aims to ensure that the tribunal’s legacy continues to benefit Cambodian society even after its main judicial activities have concluded.

Among the international tribunals, the ECCC distinguishes itself through its explicit mandate for “information dissemination”. Unlike other international tribunals based in The Hague, the ECCC’s physical presence in Cambodia allows for a closer connection with the local population. This proximity has enabled the tribunal to engage more directly with the community, including the local media ecology, addressing the needs and concerns of victims and survivors in a more immediate and relevant manner.

From courtroom to TikTok: The ECCC goes digital

As of September 2024, the ECCC has gained over 180,000 TikTok followers since its account was created in September 2023. This move raises intriguing questions: How are courts using new ways of public messaging? Can TikTok’s bite-sized videos truly capture the gravity of atrocity violence? By taking to TikTok, the tribunal is not only reaching a younger, digitally savvy audience but also reshaping its role in broader Cambodian society. This digital presence, directly led by the tribunal, aims to make the Court’s activities more accessible and relatable to younger generations, especially considering Cambodia has one of the youngest populations in Southeast Asia.

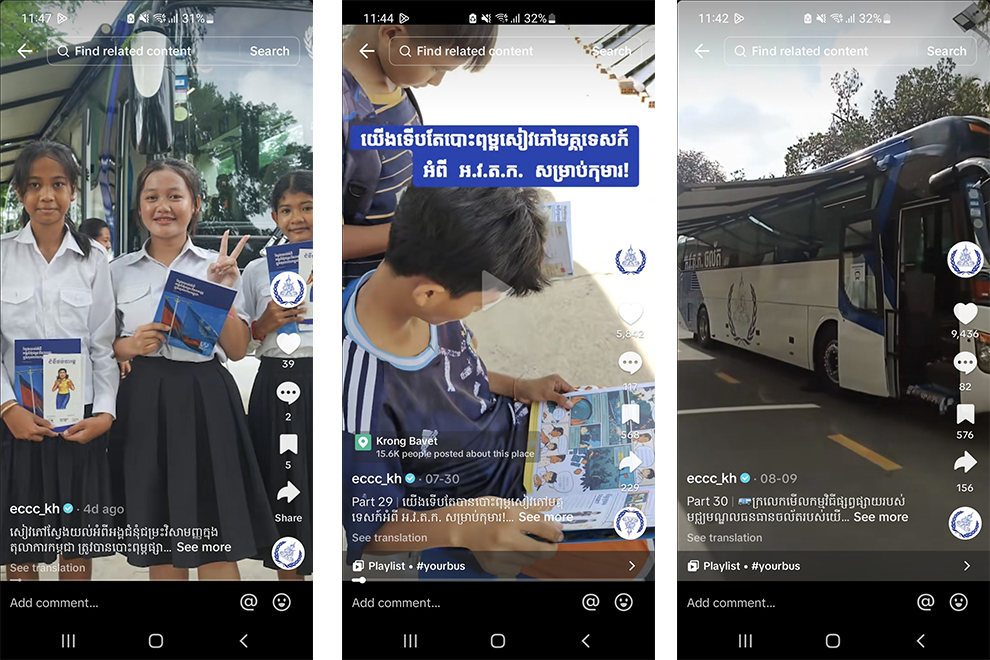

A selection of the content which is available on the eccc_kh TikTok channel of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). ECCC

The ECCC TikTok content includes voice-overs of court visits to schools, behind-the-scenes footage of court operations, dynamic infographics discussing judicial work with snippets from judges and court staff, and announcements about future outreach events.

More specific TikTok content can be grouped into campaigns that highlight the tribunal’s creative engagement strategies. One such campaign is a multi-part mini-series featuring famous Cambodian actor Young Khun portraying high school student Meng and Cambodian actress Roza Oeun portraying high school student Somaly. This series documents their journey as high school students learning about the ECCC, referencing actual crimes and the legal framework used at the ECCC. This approach leverages familiar faces in Cambodia’s Gen Z population and uses narrative-driven content to educate viewers about the tribunal’s judicial process.

Another planned campaign involves a series of interviews with civil parties, a unique feature of the ECCC where victims could participate as direct parties to the litigation alongside the prosecution and defence – a practice influenced by France’s historical legacy over Cambodia’s legal system. These interviews aim to provide personal insights and testimonies, giving a voice to those directly affected by the tribunal’s work and enhancing public understanding of the human impact of its decisions.

Adding to these digital efforts is the ECCC Bus, an innovative mobile educational unit frequently depicted on TikTok. This bus is equipped with advanced immersive educational technologies, including digital archives and virtual exhibits about the ECCC’s contributions to reconciliation and international law. It also features portable pop-up exhibitions with augmented reality installations detailing the ECCC’s judicial process. The ECCC Bus travels to schools, markets, pagodas and local communities throughout Cambodia’s 25 capital-provinces, bringing the tribunal’s work directly to the people and providing an interactive learning experience. It often accompanies ECCC school visits, engaging over 200 students per visit.

The ECCC’s use of TikTok and mobile educational units shows a shift in how courts position themselves within society. Traditionally, international courts have maintained a formal and somewhat distant relationship with the public, focusing primarily on judicial processes and official documents, with external engagement mainly involving government stakeholders and academia.

For example, the Case 002/02 appeal judgment, over 700 pages long, requires specialist knowledge, widening the gap between the tribunal’s work and public awareness, and highlighting broader criticisms of international law’s inaccessibility. While the judgment is undeniably significant, it is worth considering how many people from the public, outside the legal community, have actually read it—or even know of its existence—especially as the Court seeks to achieve goals beyond criminal prosecution. Hence, the ECCC’s residual functions present a new paradigm, where engagement, education, and visibility are equally integral to its mandate.

At the same time, young Cambodians have re-posted the Court’s TikTok content and created their own reels, filming themselves visiting the court and attending ECCC events, often adding their own remixed music, voice-overs and reflections. This user-generated content exemplifies participatory culture and digital remixing, in which audiences not only consume but also create and share their interpretations. Such cross-pollination of digital content increases visibility in new information networks and provides new spaces for young Cambodians to engage with the Court, fostering a more interactive and tangible relationship with international criminal law.

An impact beyond the screen: Access to justice?

With over seven million Cambodians over 18 using TikTok, these residual activities hold potential in Cambodia’s digital landscape, significantly contributing to the Court’s popular imagination. Whether intentional or not, the ECCC’s use of public-facing digital platforms and mobile educational units as a tribunal challenges Dr. Peter Maguire’s argument: “To ask any court, much less a war crimes court, to heal societies or teach historical lessons is asking too much.”

The ECCC’s digital innovations, including its TikTok presence, the ECCC Bus, and broader social media campaigns, represent the concept of wayfinding by providing both physical and digital touchpoints for Cambodians to engage with and visualise the Court’s work. While wayfinding refers to the methods people use to navigate and orient themselves within physical spaces, in the context of the ECCC, it extends to navigating the complex landscape of actors including victim-survivors, civil society organisations, cultural and religious leaders, local judiciary and political elite and the general Cambodian population, including youth. It directs the public to ECCC activities, such as outreach efforts, the ECCC Bus, and events at the Court’s premises, as well as access to legal resources. The TikTok account, for instance, serves both as a dissemination tool and as an amplifier of other residual functions, translating the Court’s activities into accessible content that helps Cambodia’s younger, digitally native population understand the ECCC’s role and the significance of its work in a way that resonates with them.

The ECCC Bus, a mobile educational unit, plays a crucial role in embedding the Court within Cambodian society, ensuring that the ECCC is not perceived as a far removed institution whose legacy is confined to formal academic legal scholarship. By physically bringing the Court’s presence into communities, the Bus facilitates public engagement with the ECCC’s work, making its judicial legacy more accessible and tangible for survivors and the broader population. Combined with the Court’s digital wayfinding strategies – using computational media and networked technologies – these efforts enhance communication and situate the ECCC within the everyday lives of Cambodians. This approach not only promotes a shared understanding of the nation’s healing journey but also challenges the traditional inaccessibility of international law, integrating the ECCC’s legacy into the fabric of Cambodian society.

Reaching young people is crucial due to the intergenerational impact of the Khmer Rouge era, which continues to affect the children and grandchildren of direct victims. Engaging this younger generation preserves historical memory, condemning the regime’s atrocity crimes, especially in a context where the narrative of the Khmer Rouge has been subject to recent political manipulation.

Furthermore, meaningfully connecting with youth through these channels contributes to national reconciliation by fostering an informed and widespread understanding of the past. As these younger generations grow into leadership roles, their awareness and understanding of the atrocities committed during the Khmer Rouge era – reinforced through demographically responsive methods, such as digital media – will be crucial in bringing a shared responsibility for a more united society.

Some of the young fans of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) TikTok channel. Many young people are actively engaging with the account. ECCCC

The ECCC TikTok is part of a broader range of anticipated projects outlined in the 2023 Report of the UN secretary-general. The ECCC plans to complement its traditional outreach with digital initiatives, including an online lexicon of over 1,600 legal terms and phrases, a digital database of over 18,000 victims of the notorious S-21 prison and a revamped website featuring fully searchable 2.5 million case files using “new generation technologies”.

In today’s digital age, websites and a strong digital presence are indispensable for courts. Stanford Legal Design Lab goes as far as to suggest that intuitive court websites are integral to access to justice, as they provide critical visibility, accessibility and a resource for legal information. A robust digital presence, incorporating user experience design, situates courts within the wider information space, enhancing public engagement and accessibility to the court’s work. Poorly designed, outdated digital interfaces may lead to reduced engagement, and limiting the amount of information available for public critique and meaningful use. A varied digital presence, using computational media and interactive digital storytelling, can significantly boost the court’s credibility and reach, fostering a more informed and engaged public.

As these residual functions are still in their infancy, prioritising content design for diverse communities is essential. Balancing the dynamic benefits of social media with traditional methods like textbooks, school visits, and educational programmes, which provide the depth and structure necessary for a thorough understanding of the past and official court documents, is vital. The ECCC’s under-discussed and rich jurisprudence, including head of state liability for genocide, nationwide joint criminal enterprise, and forced marriages as sexual crimes, along with insights on testimony therapy with Buddhist institutions, procedural lessons on civil party admissibility and its widely criticised funding model, offers important lessons for future international criminal justice goals.

Seizing this moment can ensure that the ECCC is remembered as a court that creatively disseminated information through the localised digital landscape in its public messaging. With social media’s researched abilities to create new cultures, shaping new e-commerce practices, and even influencing political elections, the role of carefully designed social media practices in the aftermath of a genocide trial is uncharted territory. Given the ECCC’s respected status in Cambodian society, this approach holds significant potential.

However, it is also important not to overstate the ECCC’s digital footprint, as several key considerations must be addressed. Recognising the debates around TikTok’s ethics, it is currently unclear whether the ECCC uses TikTok purely as an informal marketing tool – an extension of its social media platforms – or whether it is informed by a deeper awareness of TikTok’s role in Cambodia’s digital ecology. It is also unclear how users engage with the content created by the ECCC – as there are no public figures on engagement levels. Furthermore, the specific resources dedicated to digital information dissemination efforts, the scope of such digital humanities projects and how the ECCC evaluates the success of these projects – whether through purely quantitative metrics or qualitative feedback – remain unknown.

Additionally, it is uncertain who exactly the makers of the ECCC content are – whether there is any influence from the judges or if it is purely a decision made by the staff. The social media narratives focus on the bigger picture significance of why the Court is important for Cambodian society to move forward and victim recognition, which reflects the target audience is the layperson, rather narrowing into the technical details of the Court’s judgments and academic debates.

While it is fair to raise concerns about what is included and omitted in the narrative design – especially if ECCC judges, who often have differing views, have influence over the content – it is important to note that social media messaging related to the ECCC’s legal legacy reflects judicial rulings. Yet, the larger question of the ECCC serving as a “voice” is worthy of further study.

Yet, the digital optics remain crucial. The ECCC’s standout practices, compared to other international courts with their more reactive information dissemination approach and public engagement, represent forward-thinking in digital humanities. This innovative approach warrants further inquiry into its position within Cambodia’s digital ecosystem and networked publics, and its transformative potential in using digital platforms to present the judicial process and transitional justice mechanisms to broader populations.

The future of the residual mandate: Rethinking international courts

The ECCC’s public-facing digital innovations are by no means a replacement for the judicial process. However, evaluating the ECCC should consider the entire lifecycle of international courts, which can be grouped into three distinct chapters: from inception through negotiations between the UN and Cambodia, to trial proceedings and into the future with residual functions. Rather than exclusively focusing on the trials, these residual functions are arguably of equal importance in legitimising the judicial outcomes and rule of law aspirations for society at large.

The ECCC’s digital projects within its society-facing residual functions raise important questions about the stated goals of international criminal courts. Are they solely to try defendants, or do they also aim to promote reconciliation, facilitate nation-building and write the facts into the historical record?

These goals may be interconnected rather than hierarchal. Court-led digital storytelling, transmedia narratives, and data visualisation prompt a rethink about the goals of international courts. Moreover, as the ECCC is the last of the “golden age” of ad-hoc international courts, and with many victim communities and subsequent generations now comprising a large Gen Z population for whom social media is a key source of information, these approaches are essential.

Given their roles in promoting accountability and justice, international courts should be understood beyond their trial proceedings. International lawyers need to reflect on the purpose of international courts, especially those like the ECCC, which claim to promote transitional justice goals such as collective healing, national reconciliation, and truth-telling with debated success – fundamentally information projects.

This reflection should consider whether the objectives of the international criminal justice project are limited to exclusively criminal prosecution or encompass a broader societal impact beyond the courtroom. If it is the latter, which appears to be the case for the ECCC based on the UN agreement with Cambodia and observable practices following judicial proceedings, further consideration of information practices to meaningfully engage with local communities becomes essential.

The ECCC falls into the latter approach and has broader ambitions to connect with the wider population in the generations following the conflict. Hence, it is venturing outside the courtroom into Cambodia’s information sphere, which now has a strong digital presence. Disciplines like media and communication studies, digital humanities, computing and human-computer interaction may seem unrelated to international criminal law but offer potential for experimental collaboration in its residual functions.

Combining disciplinary expertise can explore new ways of reconciliation in digital spaces, helping a large Gen Z community reckon with mass atrocity violence. These digital practices can allow the ECCC to communicate its activities and its achievements to the broader community, aligning with the broader transnational justice discourse beyond criminal prosecutions.

As the courtroom doors closed, the ECCC’s future after the initial three-year mandate remains uncertain. However, its use of TikTok and broader efforts like the ECCC Bus demonstrate the possibilities of digitally-enabled public engagement by an international tribunal. By leveraging digital technologies with the remaining time, the ECCC can transform from a distant judicial body into an active participant in the ongoing societal processes about justice, history and reconciliation, rather than being confined to the walls of a courtroom.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the Australian government, the UN or the positions of any institutions they represent.

Andre Kwok works for the Australian government specialising in international criminal investigations, and previously served as a UN legal consultant at the Supreme Court Chamber of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.