Florida’s inmate population today is about 80,000. About 5% of them are confirmed veterans, though that share is likely far larger, research has shown.

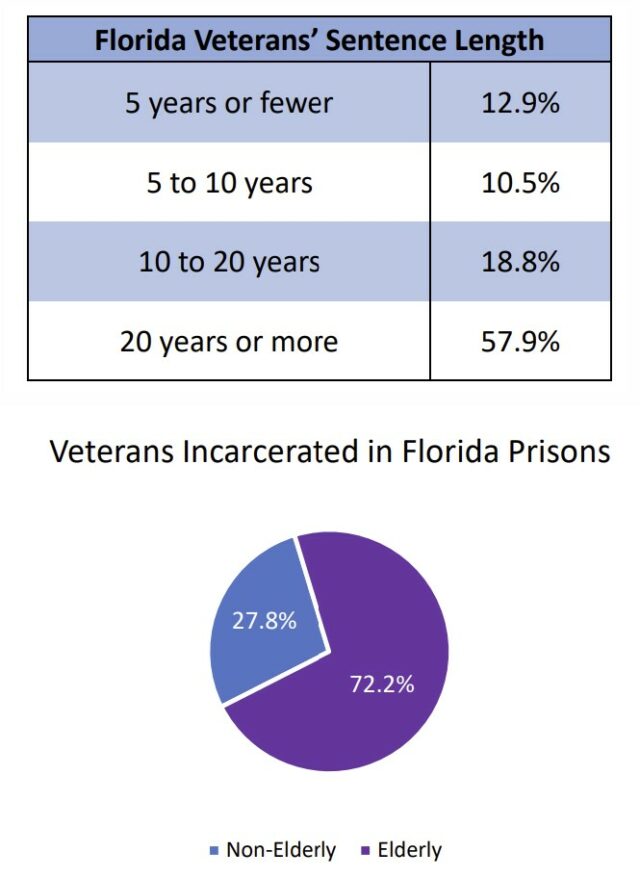

And while veterans compose only a small portion of those in Florida prisons, an overwhelming segment of them — 72% — are 50 or older.

That seems like something worth examining and addressing, according to former state Sen. Jeff Brandes, whose nonprofit Florida Policy Project just released a report outlining several recommendations for how to fix the issue.

“Having served our country, I believe we can do better for our veterans,” Brandes said in a statement. “Bringing best practices to Florida will ensure no veteran is left behind.”

The new report, aptly titled “Improving Veterans’ Incarceration and Reentry in Florida,” follows two others the self-described “policy bank” published in the past month detailing potential improvements and cost-savings for Florida’s prison system.

While the prior pair centered on recidivism and elderly inmates, the most recent one focuses exclusively on former members of the U.S. Armed Forces living behind bars in the Sunshine State.

Currently, 3,989 inmates here self-identify as veterans. All but 30 are men. But the actual number of veterans in prison is likely much higher, according to the report’s author, Dr. Thomas Baker of the University of Central Florida.

Take California for example. Last year, that state’s corrections department listed a veteran inmate population of just 2.7%, all self-identified. It was only after assessing the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) data that officials there discovered the actual share was 7.7-9.5%.

Nearly 77% of veterans incarcerated in Florida are serving sentences of over 10 years. Almost 58% are serving sentences twice that length or more.

Accordingly, almost three out of every four veterans imprisoned in Florida are 50 or older. It costs roughly twice as much to care for them as their younger counterparts. Prisons with the highest percentage of aging inmates spend five times more on average per inmate in medical care and 14 times more on prescription drugs than institutions with the lowest percentage, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Nationally, so-called “justice-involved veterans” have drawn more attention in recent years, resulting in the use of several practices by veterans-focused agencies to meet their needs while still allowing for punishment for criminal activity.

Veterans are disproportionately incarcerated — 37.2% in Florida and 26.4% nationally — for sexual offenses. For non-veteran inmates, the rates are 15% in Florida and 11.7% nationally.

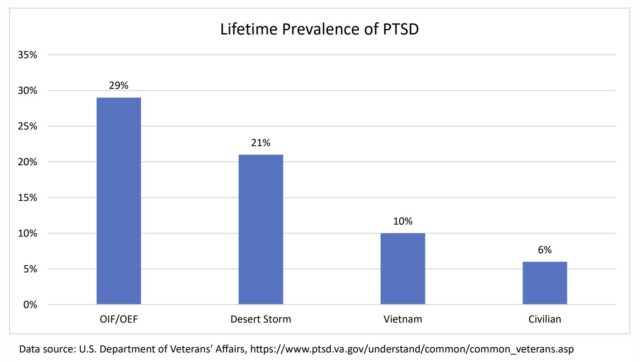

Baker posited that this may be due to the non-insignificant share of veterans who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury or both, which have been linked to violence, particularly when compounded with substance abuse.

Of note, among all other types of offenses, including violent crimes, veterans are less likely to be incarcerated than non-veterans. This, Baker said, could be due to the effectiveness of veterans-focused diversionary programs, but it also means that veterans who do end up incarcerated often serve lengthier sentences and grow old in prison.

So, what’s the solution? According to the Florida Policy Project proffered six recommendations:

— Deploy a system-wide use of the Veteran Re-entry Search Service, an automated system operated through the VA, to identify and locate veterans who are already behind bars or defendants in pending criminal cases.

— Publish veteran statistics in the DOC’s annual report and recidivism report detailing demographic information of incarcerated veterans similar to what the agency does for elderly inmates.

— Expand the use of veterans-only housing, such as the Veterans Moving Forward program in San Diego that led to nearly 41% fewer participants going back to prison after one year compared to their nonparticipant counterparts.

— Fund an expansion of trauma-informed mental health care, especially for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury symptoms.

— Appropriate funds toward developing a “re-entry roadmap” for incarcerated veterans.

— Fund a pilot program, similar to another ongoing one for elderly offenders, to test the efficacy of home confinement for veterans who must meet certain eligibility requirements, including age, time served and offense seriousness.

Veterans who are locked often face other difficult circumstances as well, such as homelessness, substance abuse and serious mental health issues, Baker said in the report.

“They are growing old in prison and are not receiving the care they earned but so often need,” he said. “The goal is to find solutions that can provide veterans with necessary services and prepare them for a successful reentry to their communities.”

Post Views: 0

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.