Argument

Vengeance Is Not a Policy

Emotionally driven reactions from Washington won’t prevent future violence. Dismantling the Gaza prison could.

The astonishing spectacle and intimate horrors of the attack by Hamas and Islamic Jihad against Israelis make it even more difficult than usual to understand why it occurred and how it can be prevented from happening again. There is simply no escaping the gut punch of seeing or hearing people of all ages—including children, teenagers, the elderly, and the disabled—being brutalized, riddled with bullets, or dragged into captivity.

The astonishing spectacle and intimate horrors of the attack by Hamas and Islamic Jihad against Israelis make it even more difficult than usual to understand why it occurred and how it can be prevented from happening again. There is simply no escaping the gut punch of seeing or hearing people of all ages—including children, teenagers, the elderly, and the disabled—being brutalized, riddled with bullets, or dragged into captivity.

The terror and pain of the victims and the agony of their families—whose appearances, accents, and life stories are so familiar to U.S. and European audiences—make it supremely difficult to undertake effective analysis.

These are real, natural, and undeniable reactions. The emotional and moral truths they reflect are crucial to an effective response. But their very intensity is dangerous.

This applies to presidents as well as ordinary people. U.S. President Joe Biden’s passionate identification with the heartbreak of the Israeli victims and his categorical condemnation of the attack as similar to those committed by the Islamic State reflect his honest emotions and match the feelings of much of his audience. But being present emotionally is not the same as being effective politically.

To prevent the monstrousness that has been unleashed on innocent Israelis from happening again and again, along with the retribution innocent Palestinians suffer as a result, we must not rely on the certainty of our revulsion; we must identify and remove the causes of the attack.

I refer not to the specific calculations, decisions, and deployments inside of Gaza that produced this specific bloodletting, but to the machine of institutionalized oppression, hate, and fear that comprises the real infrastructure of violence. The drive shaft of this machine is the horizonless immiseration, imprisonment, and trauma inflicted on the masses of people living in what Israelis refer to as a “coastal enclave.”

Palestinian youth throw stones toward an Israeli tank near the fence separating the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Yunis and the Israeli settlement of Ganei Tal on Sept. 6, 2005Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

Coverage of the Oct. 7 attacks has focused on their brutality and their uncanny similarity to events half a century ago along the Suez Canal and in the Golan Heights that shattered then-prevalent myths of Israel’s omniscient intelligence services and its fully professional and in-control military. But this time, the shock of failure is even more unnerving since the blow was delivered against civilians inside Israeli territory, not on military units stationed inside occupied territories.

Today, what is at stake is not whether the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) are better off facing enemy Arab states directly or with demilitarized zones in between. What is being challenged is the entire idea of Israel living a “normal” life as a Jewish-Zionist “villa” protected by walls of concrete, steel, and fear against the dark Middle Eastern jungle that surrounds it.

If we really do want to know and address the causes of the butchery we have witnessed, and which we are otherwise bound to witness again, we must shift our frame of reference.

The fanaticism and bloodlust of the militants who carried out the attack and perpetrated war crimes—along with their leaders’ calculations, tactics, ruthlessness, mobilization skills, and readiness to die—are not products of a special Palestinian and Muslim prowess or innate evil.

They are what can—and perhaps inevitably will—happen when masses of human beings are treated as the 2.3 million human beings living in the Gaza Strip have been treated for decades. Nor can the event be explained by the undeniable incompetence, hubris, and apparent negligence of the Israeli government and its security apparatuses. Given enough time, any system designed to contain explosive and steadily increasing pressures will fail.

Palestinians driven from their homes by Israeli forces flee via the sea at Acre during the 1948 Palestinian exodus, known in Arabic as the Nakba. PIctures of History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Anyone who tells a story knows that most of the work of the telling is done in the choice of where the story begins.

If the story of this attack begins on the holiday and Sabbath morning of Oct. 7, it becomes a 9/11 tale of innocent victims exposed to the unprovoked violence of barbarians. The plot then unfolds as the struggle to overcome the shock of a devastating blow, and then to defeat and punish the aggressors on behalf of an outraged humanity.

But if the story is seen as starting in 1948, when it was the grandparents of Gaza refugees who lived in the areas to which their armed descendants returned so briefly and violently, then the moral of the story and the requirements of a satisfying end to the narrative change drastically.

In this wider temporal framing, Hamas and Islamic Jihad did not start a war; they launched a prison revolt. Appreciating the truth of that framing requires a bit of historical background.

Before the declaration of Israel as a state in May 1948, the apron of land surrounding Gaza contained dozens of Palestinian Arab towns and villages, the largest of which was al-Majdal—what is now the entirely Jewish city of Ashkelon.

When, on Nov. 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted to divide Palestine into a Jewish state and a Palestinian Arab state, this whole area—including Gaza, its surrounding areas, and parts of the Negev Desert—was designated to be included within the Arab state. But the U.N. failed to provide money, troops, or administrators to implement its decision. Abandoning Palestine to chaos, the British, who had ruled the territory for more than 20 years, pulled their forces out of city after city, region after region. As they did so, Jews and Arabs plunged into an atrocity-filled civil war over which areas would fall under Jewish or Arab rule.

The result of this civil war, of battles between Israel and the expeditionary forces of Arab states that invaded Palestine in May 1948, and of increasingly systematic Israeli campaigns to expel Arab civilians from territories that were to have been the Arab state, was the displacement of 750,000 Palestinians; 200,000 of them found shelter in a narrow wedge of coastal Palestine occupied by Egyptian troops—what became known as the Gaza Strip. Israel’s refusal to allow those who fled or were expelled to return to their homes, and its subsequent destruction of their villages, towns, and neighborhoods, turned these displaced persons into refugees.

Ruled or dominated by Egypt from the 1949 Armistice until 1956, by Israel from October 1956 to March 1957, by Egypt again from then until June 1967, and by Israel since then, the strip’s refugee population immediately swamped its original inhabitants. Fierce resistance against the Israeli occupation in the early 1970s led to policies implemented by Ariel Sharon, who later became Israel’s prime minister, that bulldozed a grid of roads through densely packed neighborhoods, killed hundreds of Palestinians, and crushed the radical Palestinian guerrilla organizations that were entrenched in the refugee camps.

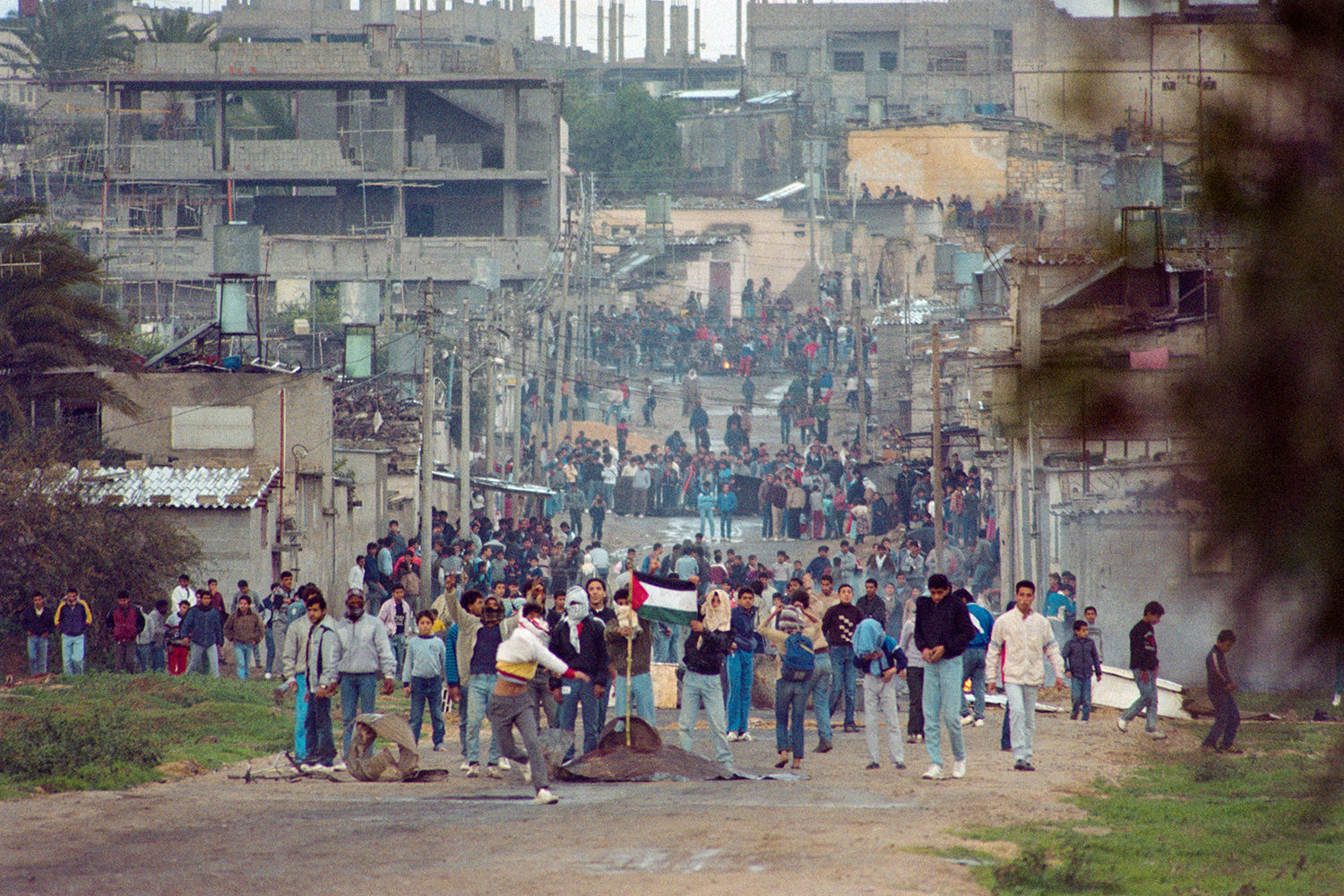

- Youths plant a Palestinian flag in the street and throw rocks in Gaza during violent demonstrations during the First Intifada on Dec. 14, 1987. Sven Nackstrand/afp via Getty Images

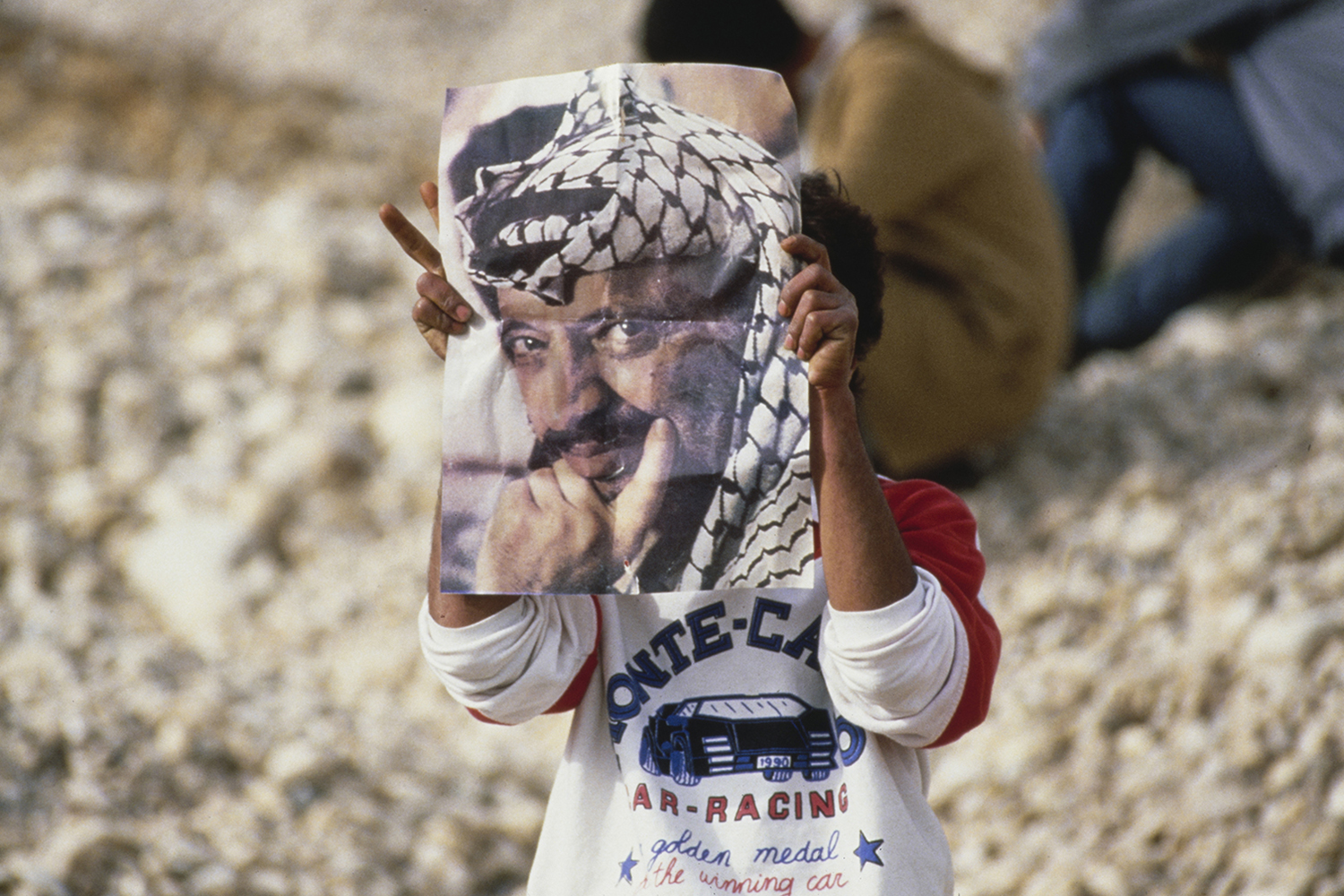

- A child holds up a portrait of PLO leader Yasser Arafat during the First Intifada on Dec. 22, 1987. Derek Hudson/Getty Images)

Seeing Muslim religious identification as less threatening than Palestinian nationalism, the Israeli authorities then offered support to the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, so that by the time of the first Palestinian intifada, or uprising, which began in late 1987, the Brotherhood could create Hamas (officially the Islamic Resistance Movement) to rival the PLO as the vanguard of the Palestinian struggle.

It may seem odd that Israel had a hand in creating its nemesis, but not quite so odd if one takes note of public comments made before the October attack—by both Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Bezalel Smotrich, the minister of finance who was largely in charge of West Bank settler affairs—that the nationalist Palestinian Authority (PA), with its ambition to build a Palestinian nation-state alongside Israel, should be seen as the real enemy, compared to Hamas, whose threat to the PA’s political position made it, in their eyes, a valued asset.

More than anything else, the Oslo Accords of the 1990s reflected a new Israeli government strategy of relying on what it hoped would be the tractability and greed of PLO leaders, rather than on the relative passivity previous governments had (mistakenly) associated with the Muslim Brotherhood. Yasser Arafat and the leadership of the PLO were allowed to return to Palestine from their exile in Tunisia with the understanding that they would suppress popular hostility to Israel in return for a state, or a statelet, they would rule. But Israel more or less doomed that idea by refusing to allocate enough authority to Arafat and his “interim” government to enable it to build legitimacy among Palestinians.

Since the signing of the Oslo Accords, the continued expansion of settlements in the West Bank, the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, and the explosion of violence associated with the Second Intifada (which began in 2000) have destroyed any prospect of a negotiated two-state solution—the once abhorred and then widely embraced, but no longer attainable, vision of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip that would provide Palestinians with sufficient realization of their aspirations to end the Arab-Israeli conflict.

In 2002 and 2003, Sharon’s government put Arafat’s headquarters in Ramallah under siege and then “transferred” him to France, where he died the following year.

In 2005, hoping to rid itself of the headache of having responsibility for Gaza’s large, impoverished, and hostile refugee population and to isolate it from the West Bank, Israel evacuated its military and 9,000 settlers from the Gaza Strip. It also refused to negotiate with Palestinian representatives about any arrangements for relations between the strip and Israel following the withdrawal.

When Hamas then won the Palestinian legislative elections of 2006, Israel, with U.S. support, responded by a failed coup attempt to forcibly replace it with rule of Gaza by Fatah. Hamas then defeated Fatah forces in Gaza and secured its political ascendancy there, leading Israel to seal off Gazans from Israel, even as some official Israeli maps refrained, and still refrain, from designating Gaza as outside of its international borders.

Gaza became a resource-starved and overpopulated open-air prison, forced to rely on Israel for food, water, electricity, trade, mail delivery, access to fishing, medical care, or contact with the outside world. From then on, Israel has effectively treated Hamas as the prisoner organization responsible for preventing the inmates—none of whom have been placed on trial, and all of whom have life sentences—from harming Israel or Israelis.

Israeli soldiers stand guard by the fence along the border with the Gaza Strip in southern Israel on Dec. 7, 2021. Menahem Kahana/afp via Getty Images

This relationship has been enforced by punishing incursions into the strip by the Israeli military: for 23 days in 2008-09, five days in 2012, 50 days in 2014, and 15 days in 2021, in the process killing more than 6,400 Palestinians between 2008 and September 2023 and inflicting billions of dollars of damage. But in between these operations to “mow the lawn,” Israeli governments and Hamas cooperated enough to prevent humanitarian catastrophes, keep Hamas bureaucrats paid, and suppress Islamic State and Islamic Jihad efforts to inflict as much damage as possible on Israel.

As in any prison, correctional authorities distinguish between inmates individually regarded as criminals and worthy of punishment and the organization representing these inmates, which can be a useful and reliable partner. And as in any prison, the wardens select “trusties” among the prisoners for rewards and to serve as informers. Thus, for example, are small but varying numbers of carefully screened Palestinians in Gaza allowed, under conditions of general “good behavior” in the facility, to leave its confines to work for wages in Israel, returning every night to prison.

The remarks cited above by Israeli ministers, preferring Hamas to the PA, help explain the fact that no Israeli government has relied more completely, or explicitly, on Hamas as an instrument with which to administer Gaza than has the recent Netanyahu governments. Satisfied that its Iron Dome anti-missile defenses and its sophisticated and expensive underground barrier had neutralized Hamas’s ability to hurt Israel by launching rockets over the prison walls or tunneling under them, Netanyahu formed an image of Hamas as having been domesticated.

In March 2019, according to Haaretz, he told a meeting of Likud Party Knesset members that “anyone who wants to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state has to support bolstering Hamas and transferring money to Hamas. This is part of our strategy—to isolate the Palestinians in Gaza from the Palestinians in the West Bank.”

Netanyahu’s policy of relying on Hamas to keep the Gaza prison from boiling over allowed his government to focus all its attention on advancing West Bank settlement, promoting a judicial overhaul to enable annexation without granting Palestinians civil or political rights, and raiding Palestinian cities and refugee camps to arrest or kill militants it could no longer rely on the Palestinian authorities to control. While the wardens were looking the other way, the prisoner organizations in Gaza put their carefully concealed plans for a revolt into effect.

Thinking about the present in this way is necessary if future violent revolts are to be prevented. The bitter reality is that Gaza is Israel’s problem because, like it or not, Gaza is a part of Israel. Though most governments and the media have been referring to the fighting as an interstate war, it is not.

Israel neither recognizes Gaza (or Palestine) as a state nor Hamas as a legitimate governing authority over its inhabitants. Instructively, Israel’s initial response to the attack was to shut off all electricity, food, medicine, and water to the entire area. No state can do those things to another state, but it can do it to a territory it surrounds and dominates.

Thus, before rejecting as outlandish the idea of Gaza as a crowded Israeli prison, consider that what goes on in Israeli prison cells and yards—such as in Beit She’an, Ashkelon, or Megiddo, where most of the inmates are Palestinians—is controlled not by the wardens but by Palestinian prisoner organizations. Those familiar with the Israeli criminal justice system know this is true, and none would imagine saying that these prisons are not located in Israel. In just this sense, the 140-square-mile prison known as the Gaza Strip, whose internal affairs are dominated by Hamas, is also within Israel.

A young Palestinian protester climbs a fence during a demonstration on the beach near the maritime border with Israel in the northern Gaza Strip on Oct. 8, 2018. Said Khatib/AFP via Getty Images

Everyone knows how brutal escaping prisoners can be, how ruthlessly prison revolts are crushed, and how many inmates uninvolved in the violence suffer as a result. We have seen the former, and we are now seeing the latter. But prison revolts are also seen as graphic signs of how ineffectively, cruelly, or counterproductively the prison was being run. They lead, often if not always, to prison reform or, in some cases, prison closure.

Indeed, this is what is needed in the case of the Gaza prison. Israel must decide: If it doesn’t want Gaza, it must let the United Nations take it over and assist it—with Israeli reparations, Gulf money, and international security assistance—toward the best future it can achieve.

If Israel wants to keep Gaza, it must, as an often-ignored part of former U.S. President Donald Trump’s plan for Palestinians advocated, open up lightly inhabited regions in the northern Negev region of Israel to hundreds of thousands of Gazans whose ancestral homes were once located there and extend equal rights to all to participate in the life of the state that rules them. Ultimately, this means, and will require, equal citizenship for all.

There are now more Arabs than Jews living between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. The problems of how they live together, and what living together eventually means for the name and the character of the state they share, are daunting. But such problems are better than those we have today, and they are better than those we will have tomorrow if the policies followed continue to address only the horror of the catastrophe and not its causes.

Ian S. Lustick is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of Paradigm Lost: From Two-State Solution to One-State Reality.

More from Foreign Policy

The Scrambled Spectrum of U.S. Foreign-Policy Thinking

Presidents, officials, and candidates tend to fall into six camps that don’t follow party lines.

What Does Victory Look Like in Ukraine?

Ukrainians differ on what would keep their nation safe from Russia.

The Biden Administration Is Dangerously Downplaying the Global Terrorism Threat

Today, there are more terror groups in existence, in more countries around the world, and with more territory under their control than ever before.

Blue Hawk Down

Sen. Bob Menendez’s indictment will shape the future of Congress’s foreign policy.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out