They call it “The Suites.” A little joke, the kind of gallows humor you can’t avoid in a place you can’t leave.

The accommodations in the Suites aren’t any more spacious than those found elsewhere in the U.S. Penitentiary Administrative Maximum — ADX for short. But they are more exclusive. The Suites consist of a special wing at the far end of everything, tucked behind H Unit, the most secure area of the highest-security prison in the country, a prison within a prison. Only two of the four cells in the Suites are occupied, and those two men are not allowed to interact with any other inmate, including each other.

Located a hundred miles southwest of Denver, just outside the high-desert town of Florence, ADX houses more than 300 terrorists, gang leaders, drug lords, and other high-risk prisoners in profound isolation; most of its residents are locked in their cells 23 hours a day. Its guest list includes Oklahoma City bombing conspirator Terry Nichols, shoe bomber Richard Reid, Colombian guerrilla leader Simón Trinidad and Mafia hitman Fotios Geas, currently awaiting trial for the 2018 prison murder of mobster Whitey Bulger. Erstwhile Miami cocaine cowboy Sal Magluta was a longtime resident until he was transferred to a facility in Pennsylvania in 2022. FBI agent turned Soviet spy Robert Hanssen died in his ADX cell last June, just a few days before Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, who’d been housed at ADX for decades, committed suicide while undergoing cancer treatment at a U.S. Bureau of Prisons medical center.

Yet even among a rogues’ gallery as infamous as the collection assembled at the federal supermax, there is a well-defined pecking order. Inmates who pose little threat of violence or escape may, over a period of years, move through a “step-down” program that eventually allows them more time out of their cells, communal dining, and a shot at transfer to a less harsh prison. At the other end of the scale are the inmates subject to “special administrative measures,” or SAMs — conditions imposed by the U.S. Attorney General that restrict not only their movement, but their ability to communicate with each other and the outside world. H Unit is home to several dozen SAMs cases, jihadists and crime bosses who are considered capable of causing “death or serious bodily injury to persons, or substantial damage to property” if their contacts aren’t severely restricted and monitored.

And then there are the two guys in the Suites, the most solitary of men. They are each entombed behind double doors in a seven-by-twelve-foot cell in the most silent corner of the supermax. The bed is a concrete slab covered by a thin foam mattress, the view a patch of sky visible from a high, narrow window. Meals are delivered through a slot in the door. There’s a stainless-steel toilet-and-sink combo, a concrete desk and stool, and a shower on a timer to prevent flooding.

There’s no one to talk to, but no privacy, either. The men are under scrutiny 24 hours a day by cameras and listening devices in the cells and by other monitoring equipment during the hour a day they are allowed to exercise alone in a small outdoor cage. FBI agents read their mail and listen in on their phone calls.

One of the men is Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the former head of the Sinaloa cartel. Known for forging one of the most powerful and ruthless drug-trafficking networks in the world, as well as for escaping maximum-security custody twice in Mexico, Guzmán is serving a life sentence in the most spartan conditions the federal prison system can provide. But even the restrictions he’s facing are arguably not as severe as those imposed on the other occupant of the Suites.

James Sabatino is 47 years old. He has a rap sheet of financial crimes stretching back to his adolescence. He is currently serving a 20-year sentence for running a criminal enterprise that engaged in mail fraud, wire fraud, and the receiving and selling of stolen goods. Despite his alleged ties to the Gambino crime family, a few assault charges in his youth, and some admitted loose talk about wanting to blow up a courthouse and “clip” certain people who might be inclined to testify against him, he is not serving time for any violent crimes. He’s a con man, not a mad bomber or a drug kingpin. Outside of Florida, hardly anyone has ever heard of him.

Yet Sabatino may be the most locked-down, buried-in-oblivion prisoner in the entire federal system. The “special measures” in his case are special indeed. He is prohibited from communicating with anyone on the entire planet, inside or outside of prison, except for two people: his 75-year-old stepmother, with whom he can have 15-minute monitored phone conversations twice a month, and his attorney. That’s an even more limited circle of approved contacts than El Chapo is allowed.

Miami powerboat racer/cocaine cowboy Sal Magluta was an inmate at the supermax prison in Colorado for decades, before being transferred to a federal facility in Pennsylvania.

Photo courtesy of Netflix

Such measures are deemed necessary because Sabatino has demonstrated an amazing talent for engineering multimillion-dollar scams even from the confines of prison. At an appeals court hearing in Atlanta last year, a federal prosecutor maintained that Sabatino’s flimflam skills provide more than enough justification for keeping him in the cone of silence he’s inhabited for the past six years.

“The problem in this case is that the defendant’s criminal history is so severe,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Scott Dion told an 11th Circuit Court of Appeals panel, “and he shows such ability to corrupt anybody he came into contact with.”

The appeals panel puzzled over a motion by Sabatino’s attorney to modify the restrictions on his client. It was a simple request but one that raised uncomfortable questions about the process by which the government imposes an almost-total ban on an inmate’s access to the outside world and how SAMs prisoners can ever “prove” they are no longer a security threat. Sabatino’s situation is more complex than that of other SAMs cases because the communication restrictions he faces are imposed not simply by prison authorities but also by the terms of his sentence. In 2017, as part of his guilty plea in his most recent scam, Sabatino agreed to the court-ordered restrictions. In fact, he demanded them, stating repeatedly that he would commit more crimes if the restrictions weren’t in place.

“These restrictions benefit the public, NOT ME!!” Sabatino wrote in a letter to his trial judge in 2022. “I hate these restrictions. They are terrible, but it is the ONLY thing that stops me. I wonder if you people have any idea of how many crimes [the restrictions] have prevented. Literally it has saved lives!! I don’t get NOTHING from this!”

Because he’s represented by an attorney, Sabatino isn’t supposed to send letters directly to the judge. But his angry, frustrated venting to the court is the only form of communication his keepers can’t muzzle, and the swaggering tone underscores the central paradox of his plight: The more isolated he becomes, the more notoriety he achieves — at least in his own mind.

Jimmy Sabatino may be stuck in the Suites, but he’s finally hit the big time.

A Con Man’s Résumé

January 29, 1995, was a black day for San Diego Chargers fans, who watched their team get blown away by the San Francisco 49ers in Super Bowl XXIX. It was an even bigger bummer for hundreds of would-be attendees who showed up at Joe Robbie Stadium in Miami, clutching tickets for which they’d paid a small fortune, only to be denied entrance.

The tickets were hot. They had been boosted by an 18-year-old high school dropout named James Sabatino, who’d obtained inside information about when a shipment of 262 tickets would arrive at a Federal Express distribution center in Florida. Posing as the president of the Miami Dolphins, Sabatino had called FedEx and insisted that the tickets be held for pickup. An associate collected the precious ducats, which were then parceled out to online ticket brokers for up to a thousand dollars each.

The brazen scheme landed Sabatino in prison for two years. It was hardly his first brush with trouble. Born in 1976, he’d been raised in Brooklyn, primarily by his father, who reputedly had connections to the Gambino and Colombo crime families. New Times writers who covered Sabatino’s exploits over the decades revealed that young Jimmy spent time in a psychiatric hospital for anger issues, then in juvenile detention facilities on weapons charges and other violations, before moving to Florida in his teens.

After the great Super Bowl ticket heist, Sabatino moved on to more elaborate capers. They were not just about money; sometimes they were a way of advancing Sabatino’s dreams of becoming a major player in the music industry. He represented himself as a hip-hop promoter. He claimed to be the nephew of Sony Music president Tommy Mottola and scored backstage face time with Julio Iglesias. Using fraudulently obtained corporate letterhead and billing codes, he impersonated record company or movie studio executives and checked into luxury hotels, entourage in tow, running up huge tabs: $16,000 at New York’s Waldorf Astoria, $16,000 at the Los Angeles Ritz-Carlton, thousands more at the Four Seasons in London, a whopping $174,000 in charges at a Hilton in Miami.

He scammed airline tickets, jewelry from Tiffany’s, and other luxury goods, insisting “the company” would handle the bill. By claiming to be working on big-budget movie or music projects involving various film stars and celebrated rappers, he persuaded wide-eyed vendors to supply him with vast quantities of computers, pagers, and cell phones with no money down.

Sabatino had a singular gift for connecting with marks and charming the pants off them. He dangled a world of possibilities, including the possibility that a stout, doughy, tough-talking hustler like himself could be a legitimate dealmaker in the glittery groves of show biz. “The easiest scam to pull off,” he explained to New Times‘ Terrence McCoy in 2013, “is to tell someone something they already wanted to believe.” Yet he also had a gift for conning himself. Several of his splashier impersonations seemed to be more about craving the spotlight than getting away with a score.

In many cases, the law quickly caught up with Sabatino. But landing back behind bars did little to deter him. In 1998, unhappy with prison conditions in Great Britain, where he had been arrested for multiple unpaid hotel bills, he made a series of phone calls to the FBI and the Secret Service, threatening to kill President Bill Clinton and blow up a courthouse.

As he hoped, the threats got him extradited. They also got him more charges, sending him to federal prison for four years.

In 2002, operating out of a jail cell in New York, Sabatino made several phone calls to Nextel Communications (a wireless company later absorbed by Sprint), claiming to be a Sony Pictures mogul in need of cell phones for a humongous flick. He managed to persuade Nextel to ship more than a thousand phones to his “office,” a FedEx outlet, ready for pickup by Jimmy’s friends, who resold them on the street. Prosecutors estimated that the scam bilked Nextel out of $3 million in equipment and service charges.

Sabatino reportedly saw little of the gravy from that grift, but that didn’t deter the judge from handing him another 11 years. While serving that sentence, he filed a lawsuit against rapper Sean Combs (stage names Puff Daddy, Diddy, etc.), asserting that he’d been cheated out of millions owed him for recording tracks of Combs’s protégé, the Notorious B.I.G., way back in 1994. To shore up his claims, Sabatino produced what appeared to be pages from hush-hush FBI files. The documents mention various intrigues surrounding Tupac Shakur prior to his 1996 murder and refer to Sabatino as a mobbed-up shakedown artist, prominent in “the Hip Hop world.”

The documents caused a sensation. The Los Angeles Times made extensive use of the materials in its investigative reporting on Shakur’s murder. But in 2008 the documents were exposed on the Smoking Gun website as a complete fraud. They were written on a typewriter, a tool the FBI had abandoned years earlier, and contained spelling errors consistent with those found in Sabatino’s typewritten jailhouse pleadings. The website slammed Sabatino as “a wildly impulsive, overweight white kid from Florida whose own father once described him in a letter to a federal judge as ‘a disturbed young man who needed attention like a drug.’”

Sabatino denied he was the author of the hoax, but his lawsuit and his claims of being a hip-hop impresario soon went up in puffs of smoke. Still, he had managed to punk one of the nation’s most powerful newspapers. And his most audacious swindle was still to come.

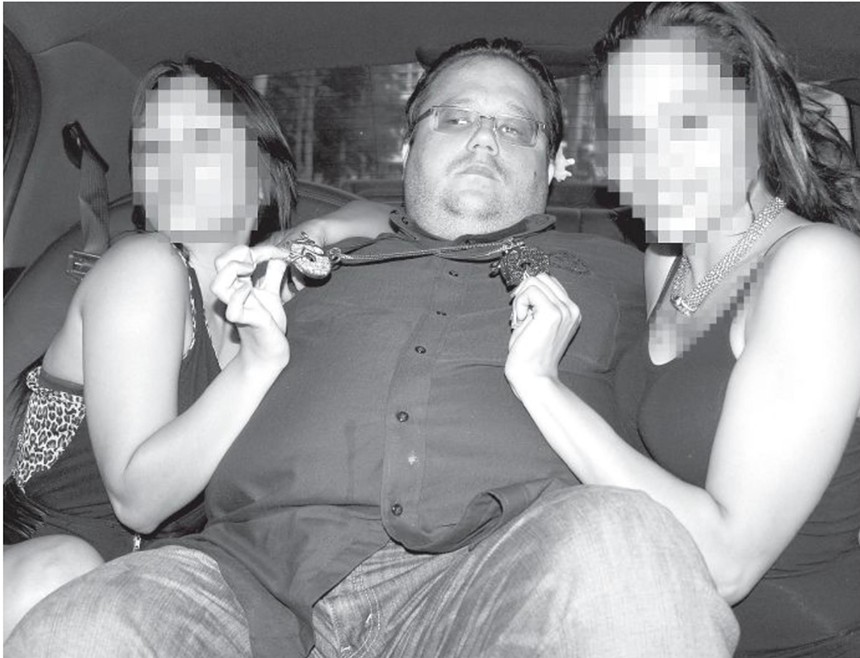

“I didn’t pay them girls nothing!” Jimmy Sabatino told New Times‘ Terrence McCoy in 2013, insisting he didn’t use escorts.

New Times file photo

Shortly after his arrival at a federal prison in Miami in 2014, Sabatino wheedled a burner cell phone from a pliable corrections officer. He created fake email addresses and began reaching out to jewelry and luxury goods stores in South Florida. He introduced himself as a Sony or Roc Nation executive, or a top honcho at Creative Artists Agency or Universal Music, and his emails had the logos to prove it. He was looking for certain goods — designer handbags, high-end apparel, shoes, and bling — that could be “loaned” and featured in music videos starring performers he represented, including Beyoncé, Jennifer Lopez, Justin Timberlake, and Jessica Biel. Eager luxury store owners and brand reps delivered the items to Sabatino confederates on the outside, who took the goods to pawn shops and funneled some of the proceeds back to Sabatino’s prison commissary account.

Although a mid-2015 search turned up the contraband phone in Sabatino’s cell, the operation continued for another two years, during which Sabatino corrupted more guards, obtained more burner phones, and plotted with co-conspirators about how to intimidate or permanently silence associates who might testify against them. On April 5, 2017, officers entered Sabatino’s cell for a surprise search and found him on the phone with one of his minions, in the process of negotiating an $800,000 sale of stolen jewelry. They seized the phone and three others.

The fraudulently obtained goods and services were valued at more than $10 million. Sabatino pleaded guilty to a single racketeering count and got 20 years. At his sentencing hearing, he readily agreed to the severe communication restrictions that were being imposed as part of his deal, conditions he requested. But that didn’t mean he was feeling remorseful.

“I don’t apologize to nobody,” Sabatino told U.S. Senior District Judge Joan Lenard. “As far as the government is concerned, they allowed this case to happen…. They should be embarrassed.”

Supermax, Meet the U.S. Constitution

A case could be made that there are many prisoners in solitary housing at ADX whose conditions of confinement are tougher, on a daily basis, than those facing Jimmy Sabatino. Muslim prisoners, who make up the majority of the SAMs cases in H Unit, have complained repeatedly of being unable to conduct group prayer, of other interference with religious rituals, of forced feedings to break hunger strikes, and of lack of mental health resources. According to court documents, the position of contract imam, a non-BOP employee who is supposed to minister to the Muslim population, has been vacant at ADX for at least seven years.

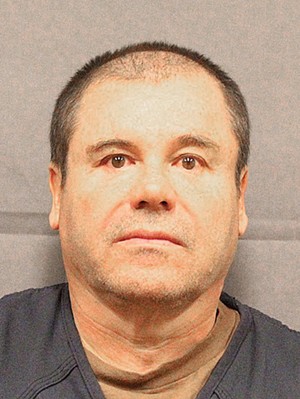

Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán is the only other resident of the Suites at ADX.

U.S. Department of Justice photo

One of the longest-running and most revealing lawsuits filed by an ADX prisoner was brought in 2020 by Mostafa Kamel Mostafa, the former imam of London’s Finsbury Park mosque, which was shut down by UK authorities in 2003 because of its ties to jihadists. Charged with aiding in terrorist plots, Mostafa fought extradition to the United States for more than eight years. Extradition was finally granted after U.S. officials assured the European Court of Human Rights that he would not be sent to ADX. In fact, his medical conditions and physical disabilities were so severe — Mostafa is missing both arms from the forearm down and is nearly blind, the result of a chemical explosion in 1993 — that the European court concluded, “there was no real risk of his spending anything more than a short period of time at ADX.”

But after he was convicted in New York in 2014 and sentenced to life in prison, Mostafa was sent to H Unit in ADX, where he’s been housed ever since, in a cell that offers few concessions to his disabilities. His claims touch on a wide range of constitutional issues, from religious freedom and disability rights to access to medical care and basic hygiene materials, and whether he can have phone conversations with his grandchildren.

Compared to Mostafa’s raft of grievances, Sabatino’s return to court last year, seeking a change in his communication restrictions, seems like a modest request. All he was asking was that one name be added to his list of approved contacts, that of his stepmother’s fiancé, so he would have someone to contact about his stepmother’s condition while she was hospitalized. However, the request had confounding implications for SAMs protocol. Does the burden of proof fall on the government to establish that a prisoner’s requested social contact poses a security threat, or can it ban the prisoner from talking to anybody in the world until the prisoner somehow proves there is no threat?

“The way the statute reads, they have to prove probable cause,” says Israel Encinosa, Sabatino’s attorney. “That is the argument we were making. All we were asking is that they be reasonable.”

Ultimately, Encinosa says, his client decided to drop the issue for now, without precluding other court actions in the future. Although he can’t share any details of his own communications with Sabatino because of the SAMs restrictions, Encinosa says he has had “good conversations” with him.

“I don’t think too many people could do well under these conditions,” he says. “I don’t know which is worse — to be alone or to be with other inmates. I don’t know which I would choose in Jimmy’s situation.”

Jimmy Sabatino, inmate 30906-004, is slated for release from the U.S. Penitentiary Administrative Maximum (ADX) Florence in 2035.

U.S. Bureau of Prisons (USP Florence ADMAX)/U.S. Department of Justice (Sabatino)

If he had his druthers, Sabatino knows what he would choose. A prosecutor’s suggestion that Sabatino actually preferred “having a cell all to myself” prompted an outraged response in one of the inmate’s long-winded letters to Judge Lenard.

“Think about it a minute,” Sabatino wrote. “I am in the harshest prison in the country. I have no contact (physical contact) with anyone. I hardly ever leave my cell, and when I do, I am in chains, black box over my cuffs, shackles, and surrounded by three officers with black clubs. He thinks that is a luxury? Tell him to try it. He wouldn’t last a week.”

He went on to boast that, before his move to the Suites, he lived “like a king” in prison, surrounded by admiring inmates who were happy to clean his cell, do his laundry, and cook for him. “I am actually quite well-known throughout the BOP. You can put me in any penitentiary in the country and there will be people I know personally, and even more who know of me…. All of them know that I can change their lives. That I can make them more money than they ever dreamed of.”

Being the most isolated prisoner in the federal system may add an aura of menace to the legend of Jimmy Sabatino; at the same time, it makes it more difficult for him to promote his brand. A docuseries about his exploits is said to be in development by fellow Miamian Billy Corben, director of the Cocaine Cowboys franchise. Corben’s production company did not respond to a request for comment, but gaining access to Sabatino in his current digs would be no mean feat. Not only is he prohibited from speaking to the media because of his SAMs status, but it appears that prison officials haven’t granted any journalist a face-to-face interview with any inmate at ADX since 9/11, aside from a well-orchestrated tour or two. (An ADX spokesperson could not provide any specific instance of media access to individual inmates over the past 20 years but insisted that “all interview requests are reviewed for consideration on a case-by-case basis.”)

For a man with Sabatino’s can-do attitude, such challenges are meant to be overcome. Or, as he put it in a letter to the judge, “The only reason I am OK is because 1) my father raised a man! I am strong and will [not] be broken, 2) I have Allah in my heart, and 3) I live for the day that I can really achieve my goals.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.