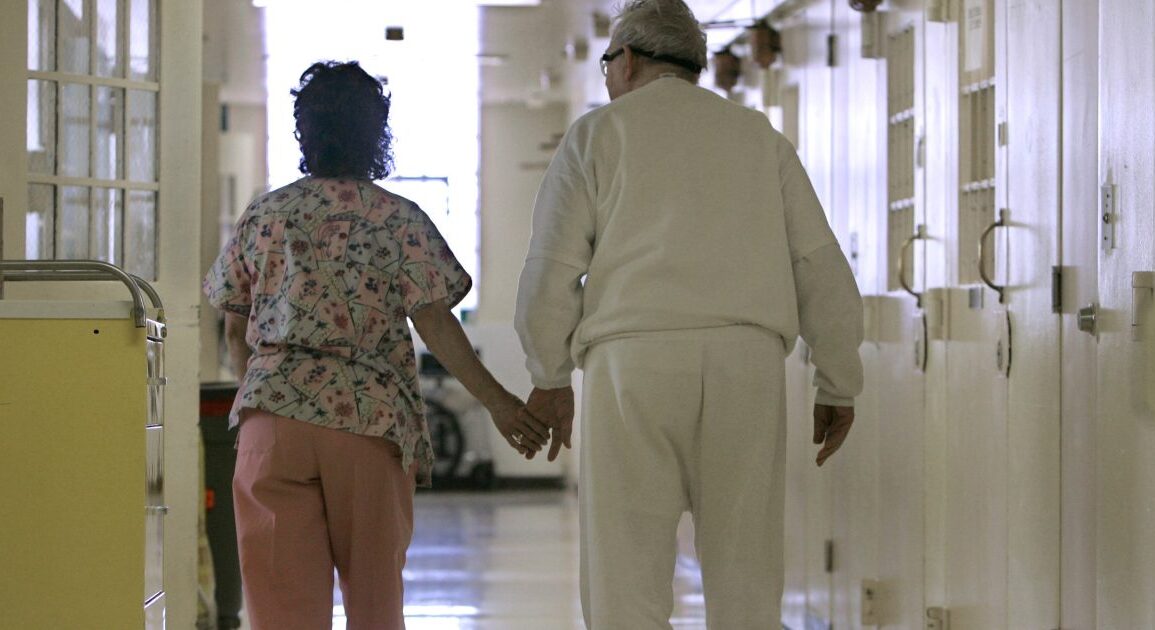

Fishkill Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison 70 miles north of New York City, made history in 2006 when it opened a 30-bed dementia unit, the first of its kind in the country. Inmates can wander freely through the brightly lit rooms that look more like the inside of a nursing home than cells.

Today, specialized units designed to accommodate America’s elderly prison population are no longer making headlines. Prisons nationwide are reckoning with the challenges of caring for inmates as they grow old, and in some cases, die behind bars. Facilities already facing staff shortages are further stretched by the additional care older inmates need, and some staff lack the training needed to work with aging prisoners.

Some criminal justice advocates are increasing calls for the compassionate release of elderly inmates and a revamp of the sentencing laws that landed them behind bars for decades. But others urge caution, pointing to the need for individualized approaches that don’t disregard the victims of the crime.

Many prisons classify their inmates as elderly once they hit age 50 or 55. Research shows that prisoners typically have more chronic health conditions and tend to suffer age-related decline more quickly than those who are not behind bars.

In 1991, prisoners 55 and older accounted for 3 percent of the prison population, but by 2021 that percentage jumped to 15. By 2030 it’s estimated that roughly 1 in 3 prisoners will be over age 50, a total of about 400,000 inmates. Already, 30 percent of inmates serving life sentences are at least 55.

Rachel Wright, the national policy director for the conservative criminal justice reform initiative Right on Crime, said the steep rise in America’s incarcerated elderly is fundamentally shifting the mission of the prison system from punishment and rehabilitation to “essentially functioning as a nursing home.”

In Minnesota, the state’s Department of Corrections cares for elderly inmates with serious health conditions in two specialized care units. Inmates receive dialysis and other hospital-level nursing care in the Transitional Care Unit at the state prison in Oak Park Heights, Minn. Here the cells are outfitted with wheelchair accessible sinks and doorways and reclining hospital beds. The 100-bed Linden Unit also provides daily care to inmates who need help dressing and showering or managing a chronic disease.

Jolene Robertus, the department’s assistant commissioner for health, said the department is in the early stages of creating its own dementia unit. “This is the direction that many states are going,” she said.

The prison has fewer options for elderly people who don’t need around-the-clock nursing care and live with the general population. These inmates can work a job and participate in activities, but still need slight accommodations. Prisons were “designed for young, healthy individuals,” Robertus said, from the height of the beds to the weight of the cell door.

“We haven’t made all the adjustments,” she said. “But these are the things that are on our radar.”

The U.S. prison population reflects broader demographic changes in the United States. The population of Americans aged 65 and older grew five times faster than the rest of the population between 1920 and 2020. Americans’ median age rose from 30 in 1980 to 38.9 in 2022, climbing past 40 in nearly one-third of states.

Shifting demographics corresponded with a push for more punitive sentencing laws during the 1980s and 90s, said Ronald Aday, a professor of aging studies at Middle Tennessee State University. Aday, who authored Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections, pointed to the creation of mandatory minimum sentences and three-strikes laws that mandate much harsher penalties for the third offense, even if on its own the offense wouldn’t have warranted a life sentence. California, for instance, requires judges to sentence offenders who already have two previous serious felony convictions to a minimum of 25 years in prison.

Governments also began incarcerating people more often. Today, there are more people serving life sentences than the entirety of the U.S. prison population in 1970, which was less than 200,000 people. In 2022, U.S. prisons held about 1.2 million people.

States spend anywhere from $23,000 to $307,000 annually per prisoner, depending on where an individual is incarcerated. A 2013 study found that older prisoners cost prisons between three and nine times more than younger, healthier inmates. “We’re sending the taxpayers the bills to keep these people in prison,” Aday said.

Like Minnesota, Michigan has two specialized units for prisoners who need specific accommodations and some level of assistance on a daily basis. Another inpatient care unit houses inmates who need more long-term, intensive medical treatment. There’s also a hospice program.

Many of the aides who sit with the dying are younger fellow prisoners. They read with the elderly inmates, help them write things down, and hold vigil in their last hours. “No one dies alone,” said Marti Kay Sherry, the health services administrator for the department. “They realize that at some point this could be them, or it could be a family member, and they wouldn’t want them to be alone.”

Younger prisoners are also trained to assist in the other specialized units, pushing wheelchairs and reminding older inmates about their next daily activity.

Sherry said ensuring that prison staff receive the right training is an ongoing challenge. The department hopes to build more partnerships with groups in the community who specialize in caring for the aging, and could support prison staff and the inmates who assist them.

Jose Rojas, a retired correctional officer and GED teacher for the Bureau of Prisons, said the increase in elderly inmates exacerbates wider staffing shortages. When Rojas worked at Federal Correctional Institution Coleman, a facility housing 2,043 inmates in central Florida, the BOP had classified many of the prisoners in medical care levels three and four, bureau designations for inmates who require frequent clinical visits, daily living assistance, or nursing care.

“In other words, we do a lot of hospital runs,” he said. BOP staff accompany inmates on hospital stays and doctor visits, further straining staffing levels and forcing the prison to temporarily place prison teachers and nurses in correctional positions.

Every U.S. state except Iowa allows for some form of compassionate release, often referred to as medical parole, as prisoners near the end of their lives. But Aday with Middle Tennessee State University said the process is “underutilized.” He pointed to research showing that released elderly prisoners are less likely to be rearrested. On average, as many as two-thirds of former prisoners overall are rearrested, but a 2018 study of 200 inmates originally sentenced to life in prison documented a recidivism rate of only 3 percent.

Compassionate release requests can still take years. “The wheels turn so slowly that, in many cases, the person is already deceased,” Aday said. It’s a complicated process. Officials weigh what kind of crime the person committed, their behavior in prison, and evidence of rehabilitation.

Ashley Nellis is the co-director of research at The Sentencing Project, a group that advocates for decarceration. She’s one of many criminal justice advocates who argue states should significantly ramp up compassionate release. “There’s just no public safety purpose to keeping these people incarcerated,” she told me.

But calls to expand compassionate release en masse pose critical questions about justice and proportionality, said Heather Rice-Minus, the president and CEO of Prison Fellowship. “We don’t support the release of prisoners solely due to advanced age,” she said. “We need to hold people accountable for crime. But I also think that we’ve lost sight of what is proportional.”

Rice-Minus argued most Americans have grown numb to decadeslong sentences and lost sight of what constitutes a proportional punishment. While Prison Fellowship advocates for changing laws that impose unduly long sentences, Rice-Minus noted that enacting justice may sometimes require someone to remain in prison until their death.

Still, the vast majority of prisoners in state and federal prisons will eventually be released. And elderly inmates who have spent decades of their lives behind bars will need extra support as they transition into a foreign environment filled with unknowns, said Cary Sanders, CEO of the South Carolina-based reentry ministry Jumpstart.

Most elderly prisoners aren’t prepared for how much their communities have changed. “A lot of these people have been out of society since before the iPhone came out,” Sanders said. “To try to navigate the web and sign up for things online … can be quite overwhelming.”

While Jumpstart typically houses former inmates temporarily while they find employment, pay legal fines, and become independent, Sanders told me they reserve 10 beds for those who are too elderly or disabled to go back to work.

“Their parents have passed away. Their siblings are often elderly as well,” he said, “And so it’s either a program like Jumpstart or it’s homeless under a bridge.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.