Our political and cultural systems are obsessed with exploiting fears about crime. But it wasn’t always this way.

1964 GOP presidential nominee Barry Goldwater.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

You had to watch your back on the grimy cobblestone streets of Victorian Era London. Ever since the explosion of the Industrial Revolution, crime had become a constant source of anxiety. Even with the installation of a new network of gaslit lamps and the implementation of what would become some of the first modern policing practices, the poorest slums of the city were still seen by the upper classes as virtual pits of hell. Racialized minorities, immigrants, poor women, queer men, and orphaned children were especially sensationalized as being inherently deviant.

The ghettos of London, Manchester, and Glasgow were indeed home to astonishing amounts of destitution, grime, pilfering, and violence of all shapes. But if the British bourgeoisie wanted to find a culprit for the wretched condition of the slums, they need only have looked in the mirror. As Friedrich Engels noted in his influential study The Condition of the Working Class in England, criminality had risen rapidly during the 19th century in conjunction with the boom in commercial manufacturing, as poor workers were condensed into filthy tenements and isolated politically and socially—all by the same classes that now sought to constrain the very people placed in such dire predicaments.

For Engels, there was something almost apocalyptic about the social cleavage that he was observing.

“In this country,” he wrote, “social war is under full headway, everyone stands for himself, and fights for himself against all comers, and whether or not he shall injure all the others who are his declared foes, depends upon a cynical calculation as to what is most advantageous for himself.”

Now, almost 180 years later, many of the crises that emerged during industrialization—and the fundamental forces that defined them—continue to fuel our own, American understanding of the social contract. And just as in Engels’s day, the fear of crime looms above almost all other concerns.

After a 30-year dip in the kinds of grisly crimes that inherently produce large-scale panics, the years since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic have produced a rebranded, yet familiar hysteria around criminality, how we should reckon with it, and who is to blame. Call it the crime anxiety industry—that toxic brew of politically weaponized fear, racial and class animus, copaganda, and media sensationalism that leaves people certain that the country is spiraling out of control and that the only way to right the ship is through the buildup of the carceral state.

Two things are undoubtedly true about crime in America. The first is that we experience substantially more violence than other industrialized countries—a trend that has remained constant regardless of overall crime rates over the past half-century. The second is that, as in Victorian London, this violence is observed in a vacuum and treated as separate from the myriad of other deadly disorders in our highly unequal society.

It is beyond urgent that this country starts to pay attention to the forces that embed the crime anxiety industry deep within our national psyche. We need to understand why we comprehend violent crime in such essentialist terms, what we mean when we talk about crime, where we should begin in unraveling the socioeconomic character of crime, and, most importantly, how a political and popular culture that teaches you to view every person as a potentially existential threat makes building a better society impossible.

While the numbers on violent crime in recent years are complicated, the fact remains that murders and mass shootings saw a noticeable spike following the onset of lockdown and the George Floyd uprisings. (The murder rate has since dropped sharply.) This, alongside a culture that produces loneliness and isolation and encourages fear, has created a particular climate of anxiety that, while it does not purely emanate from fantasy, is grounded in an outsize level of paranoia.

The fear around crime is also unevenly distributed. For example, you’re more than twice as likely to die of a drug overdose than a homicide, yet the mass deaths of drug users are not treated with the same reverence as, say, those of Gabby Petito or Eliza Fletcher. Poverty has become the fourth-largest cause of mortality in the United States, but we’re more interested in criminalizing those afflicted by it than in intervening. Wage theft and overtime violations by employers demonstrably outpace all other forms of theft, but I have yet to see conservative media fearmonger about pernicious business owners. Gun violence—often self-inflicted—is a greater threat to people in rural areas as opposed to urban ones; and despite living in a “ golden age” of massive financial fraud and larceny, we seem more preoccupied with surveilling employees of retail giants than keeping an eye on the executives behind them.

This is to say nothing of the fallibility of crime statistics: Large swaths of police crime data are not figured into national statistics (and acts of murder, rape, and theft committed by the police tend to be obscured from the overall count), staggering numbers of innocent individuals who are charged and found “guilty” in courts do so because they are compelled to enter plea deals, and the numbers surrounding crimes like child abductions are diluted by false positives.

In short, the crime anxiety industry’s simplistic, cops-and-robbers conception of which types of people commit crimes, and how those people should be punished, bears little resemblance to the chaotic reality of our leviathan-like carceral apparatus.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

But this hasn’t stopped Americans from often conceiving of crime in one-dimensional terms. As institutions have failed to stem the tide of homelessness, addiction, and mental illness, and as the crime anxiety industry churns on all fronts—the neverending IV drip of 24-hour news, apps like Citizen and NextDoor that pump a constant drip of supposed crime updates into peoples’ phones, true-crime content, and craven “ crime watch” social media accounts—public perception across the country seems to indicate that many believe the barbarians are at the gates.

This is nothing new. During the 1970s and ’80s, the so-called “Golden Age” of serial killers and child abductions, it was institutions like the FBI that manufactured the kind of Stranger Danger paranoia that colors our collective imagination about The Criminal. At one point in time, mass media and the Bureau taught us to believe that fiendish sadists conducted thousands of ritualistic homicides every year, only for it to be revealed that such cases contributed to less than 1 percent of murders.

These extreme cases of harm, as the historian and author of Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American Carceral State Paul Renfro told me, rewire our understanding of our shared social space. Cases like the abduction and murder of children become tabloid fodder—exaggerating the dangers of the world as a whole.

“It creates this set of reference points that enable people to think that they know, on a first name basis, in this kind of parasocial way, people like Jacob Wetterling, and the families that are affected. And that shapes their behavior,” Renfro said.

“It shapes how they understand, how they craft narratives about the world. And because they’re so visceral and have this emotional resonance…they are always going to trump…or kind of override these clinical explanations, right?”

Recent polling bears this out: It indicates that concerns about crime have reached highs not seen since the early ’90s, when crime numbers reached their zenith across the country. This is all despite the recent resurgence in crimes—in some places, in some categories, among some demographics—being nowhere near as prevalent.

Furthermore, it appears that the general population is relying more on visceral impulses than anything else. In Minnesota, which, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, became the epicenter of both the call for public safety transformation and bad-faith arguments against such measures, 54 percent of residents believed crime had risen in the state, but only 17 percent felt unsafe in their own neighborhoods. Nationally, half of all Americans believe crime is a national problem, but only one in 10 thought it was relevant to where they lived.

Meanwhile, for those caught between the trifecta of gun violence in poor communities, ineffective public safety, and the brutality of mass incarceration, the dehumanizing churn of our one-size-fits-all approach to social ills carries on.

For both the reactionary right and the center-left, these anti-social facts have been twisted into fearmongering narratives that can be relentlessly exploited for political gain. Agents of the GOP saw an opportunity to frame the BLM movement as both sympathetic to and the cause of a broader ascendence in criminality; almost giddy at the thought of being able to blame Black people for foolishly believing that the police and mass incarceration actively harm them in a plethora of ways.

This distortion of Black political struggle was then joined with contradictory ideas that Black people were both apathetic and uniquely concerned about crime. Observers asserted that their “oppositional culture” not only neglected violence in Black areas but actively encouraged it, even as conservative pundits and left-bashing politicians simultaneously sought to promote the idea that it was actually elites, not the overpoliced, who wanted to transform the criminal justice system. And, thus, the only solution, one that Black people actually wanted, was to use brute force to force such neighborhoods into submission.

“There’s this kind of dominant narrative out there that Black communities don’t care about crime, that Black leaders never really went up against safety deprivation, which they did time and time again, if you look at the history,” Vesla Weaver, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins, explained. “They are some of the most active voices against both the under responsiveness to safety, deprivation in their communities, and the over the kind of police occupation and terror and brutal ballistic treatment.”

These “critiques” have been paired with the idea that liberal big cities have essentially sidelined law enforcement, despite the fact that no police department in the country has been defunded. Additionally, the right has pushed the conspiracy that a network of George Soros–backed prosecutors is engaged in an effort to turn major American cities into dystopian wastelands.

At the same time, establishment Democrats simultaneously blamed this activism (and its supposed connection to the supposed crime wave) for their electoral problems, and diminished the materiality of public safety failures by pointing to murder spikes in Republican-controlled areas—all while doubling down on archaic policing and punitive policies.

Look no further than the rise of carceral Democrats like New York City’s Eric Adams, who ran on a throwback tough-on-crime campaign. As mayor, his revamped take on “Broken Windows” enforcement runs up against the reality that a decrease in brute force policing ran alongside an overall decline in violent crime over the past decade.

Regardless, both parties use the crime anxiety industry to bolster their standing with the affluent and afraid. Sometimes they do it so successfully that they become trapped by their own apocalyptic rhetoric. That’s what happened with Adams, whose constant, wildly inaccurate insistence that New York City is experiencing an unprecedented crime wave was so eagerly amplified by the news media that Adams eventually pleaded with journalists to tone things down.

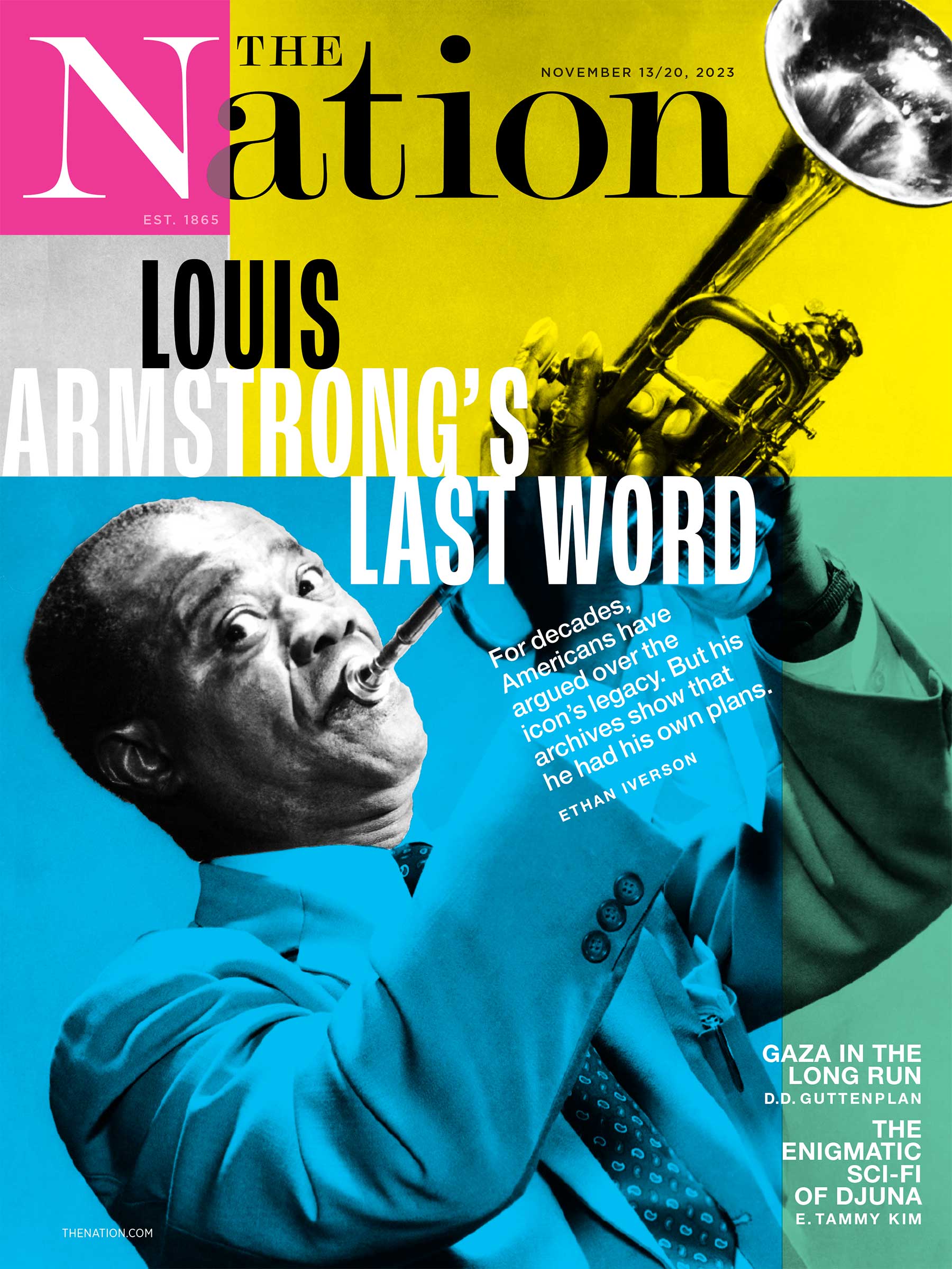

But the weaponization of these concerns wasn’t always so commonplace. It wasn’t until 1964, during the year’s presidential race, that the campaign staff for Republican nominee Barry Goldwater released a short film called Choice, which even for the time was considered too racist and inflammatory. The agitprop, narrated by a righteous, booming narrator, rails against the moral decay of America as footage of Black citizens looting storefronts intertwined with shots of garish, neon strip clubs plays on a loop.

“Up to the courts of law, justice becomes a sick joke. New loopholes allegedly protecting freedom now turn more and more criminals loose on the nation’s streets. Their freedom is a license to prowl, to ravage,” scolds our stoic raconteur over chintzy stock music. The cheesy delivery would be funny if it didn’t presage the onslaught of state violence to come.

The film ends with a stern cameo from John Wayne begging upstanding Americans to “pull the lever” for Goldwater.

Goldwater found the film too distasteful and ordered it pulled from the air, but his vicious sermons on the upsurge in criminality continued. “At home our crime rates soar, rising four times as fast as our population. The quick buck, the dime-novel romances, pride and arrogance, morality that works on a sliding scale depending on your position,” he once told a crowd of supporters.

Such rhetoric, according to the historian Rick Perlstein, was unprecedented. But since then—from Richard Nixon to Hillary Clinton—it has become commonplace in American discourse to allude to criminal behavior and moral decline in the same sentence; to imagine that a certain set of the population is imbibed with a kind of hostile, aggravated essence that drives them to terrorize the Silent Majority.

The primal seductiveness of this framing, and the machinery of the crime anxiety industry, has contributed to a kind of national schizophrenia about how to “solve” crime.

Americans broadly seem to understand, given widespread, cross-partisan support for scaling back mass incarceration and police reform, that the criminal justice system is a monstrosity that is more invested in breaking individuals than recuperating their humanity. And yet, at the same time, we seem unable to break from its ideology: There are the bad people who choose to be bad, who lurk around every corner, waiting to harm you, specifically. And they must be kept separate—punished for their innate, neverending quest to be bad.

Never mind that it is well understood that crime is directly connected with economic deprivation, childhood abuse, and other forces that isolate and compel individuals to do harm. Never mind that much of the interpersonal violence is centered in the domestic space or among people with a shared past—not the product of a sinister cabal of child molesters, serial killers, and mobsters. Never mind that, despite having a cumulative police budget that would make it the third-largest military in the world, American law enforcement has failed to stem the carnage that makes the US an outlier among the postindustrial powers.

As sociologists John Clegg and Adaner Usmani have noted, the underlying logic of our political economy has reinforced punitive methods of human management over redistributive ones. Since the end of the Second World War, we’ve become more invested in the idea that we can police and imprison our way out of social stratification—as opposed to intervening federally and economically to create a better society. We see it as the state’s job to punish those who cannot exist functionally within our market-obsessed system.

(Take the case of Baltimore, an incredibly impoverished municipality that has the distinction of having spent more money per capita on policing than any other American city, yet consistently continues to record some of the highest homicide rates in the world.)

Nothing better demonstrates this intersection quite like one of our most consequential presidents: Ronald Reagan. At the beginning of his first term, as crime continued to plague major urban centers, Reagan’s administration initiated a Presidential Task Force to explore how victims of crime had been failed by the criminal justice system.

“After decades when most concern was focused on the rights of criminals, the public has recognized that the victims of criminals have rights also. Guided by the recommendations of the President’s Task Force on Victims of Crime, my Administration is striving to ensure fair treatment for innocent victims,” Reagan said in a 1985 proclamation.

At the same time, Reagan’s economic policy would signal the end of America’s already withering welfare structures. The neoliberal ideology, which glorifies the market, destroys public goods, ignores the sociological havoc it wreaks, and maintains itself through intensive state violence, would soon reign supreme.

What we now have then, is a situation in which impoverished, high-crime localities are treated as sacrifice zones, all while our ever-more-privileged upper class silos itself off from the grim consequences of the world that it has created.

Instead of actually doing anything about the root causes of crime, people in power are now exploring unconventional warfare on those deemed too openly defective.

We already see this playing out on both the streets and the corridors of power: vigilantism that results in murder and assault of unhoused people, the rise of paramilitarism and parapolicing, large-scale sweeps of homeless encampments, neo-incarceration of those suffering from mental illness, the continued repression of migrants, calls by presidential candidates to initiate military campaigns against drug cartels, and proposals by former presidents to round up the most marginalized into tent cities.

This kind of cowboy carceralism is fueled by the new crime anxiety industry buzzword “Anarcho-Tyranny”—the idea that the elites at the top and the untouchables at the bottom are engaged in an assault on the wholesome, hardworking middle class—and their belief that this is the new status quo; that a war of all against all is upon us. “Have a plan to kill everyone you meet,” a Fox News guest, referencing an infamous quote by Gen. James Mattis, said after a mass shooting in Allen, Tex.

Without any cure for these underlying issues, such “solutions” will continue to proliferate. The more we bowl alone, the more we buy into the paranoid style, the more appealing such unorthodoxies will be normalized. As we have become more and more distant from each other in every facet of social existence, the idea that every person could potentially victimize us drives us further and further away from organizing for new rights and new remedies for the drivers of violent behavior—like decreasing eviction rates, creating a national, holistic care system uncoupled from profit, and opening up more public space for communities to exist in.

But until we create a domestic Marshall Plan, many will pine for the old order of the classic carceral catalog—especially as the possibility of collective action is shelved in favor of ineffective and piecemeal corporatist approaches to inequality.

In 1902, almost 60 years after Engels’s now famous treatise, the American writer Jack London descended into the Big Smokes’ infamous East End ghetto.

Even the colonial fixers London attempted to enlist, who had braved, in his words, “Darkest Africa or Innermost Thibet” implored him to seek a police escort. After all, it was only a decade prior to London’s attempts at proto-gonzo journalism that the scandalous and devilish Jack the Ripper had haunted these same streets.

London wouldn’t heed their warnings. Instead, he explored the depths of crime, disease, precarity, addiction, and mental illness that defined life in the massive slum.

People of the Abyss, a novella-length piece of reportage wherein the American journalist spent weeks living among the city’s most downtrodden—even going to far as to simulate the experience by navigating the crooked, piss-stained streets without any money or quality clothing—would capture the phenomenon of urban destitution in a deeply humanizing way.

London saw the violence and social decay of the East End as a consequence of politics, not of spiritual failings or biological inevitability. There were in fact human beings living in the abyss. Indeed, he saw the managers of the British colossus as the true felons: For all their Victorian principles and elitist virtues, the ruling class of the world’s most expansive empire seemed unable to confront its amoral, ineffective domestic policies.

“It is inevitable that this management, which has grossly and criminally mismanaged, shall be swept away,” London wrote. “Not only has it been wasteful and inefficient, but it has misappropriated the funds. Every worn-out, pasty-faced pauper, every blind man, every prison babe, every man, woman, and child whose belly is gnawing with hunger pangs, is hungry because the funds have been misappropriated by the management.”

It is London’s framing that may best serve us in the present. The crime anxiety industry is about distracting us from the criminal ideology behind our economic conditions and those who have financially benefited from them. Their “misappropriation,” as London lightly put it, has generated levels of violence that would make even the most maniacal spree-killer or cutthroat mobster blush.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.