With a blaring siren, the Honduran Prison Police patrol car dodges through Tegucigalpa’s congested morning traffic, screeching into the Escuela Hospital. In the trunk with two other women is Adriana,* a former Mara Salvatrucha 13 (MS13) gang member, squeezing her leg with her hands to try to contain the bleeding from an open wound.

The paramedics and police begin to get the women out of the patrol car. Two women, seriously wounded by bullets or machete cuts, are placed on stretchers and quickly admitted to the operating room. Meanwhile, Adriana is placed on the sidewalk, where she waits her turn to receive medical attention.

At that moment, an uncontrollable weeping takes hold of her. A reporter approaches and asks her what happened. She cannot hold back her tears. She covers her face with her hands and her long black hair, and only manages to say, “They got into the section with an AR-15. The ones from the 18.”

The events that unfolded the morning of June 20, 2023, at the National Female Penitentiary for Social Adaptation (Penitenciaría Nacional Femenina de Adaptación Social – PNFAS), located 40 minutes outside Tegucigalpa in the town of Tamara, may have been the deadliest massacre ever recorded in a female prison in Latin America.

At least 46 female inmates were killed amid a fire and a hail of bullets from alleged Barrio 18 gang members who had managed to break out of their cells to attack their rivals in the MS13, according to Honduran authorities and media.

For the women of the PNFAS, the massacre was not entirely unexpected. For months, they had reported in tension between gangs.

But the high command of the prison system seemed to be taken by surprise. It was clear that they had underestimated the potential for violence among the inmates despite a similar massacre just three years earlier when, in May 2020, the Barrio 18 had used knives and machetes to brutally murder six alleged MS13 collaborators in the prison.

In April 2023, just two months before the recent tragedy, InSight Crime visited the PNFAS and interviewed 30 inmates and prison staff. Among them was Adriana, who already had survived the 2020 massacre after spending several hours in hiding.

“I’m very afraid. They don’t protect us here,” she said.

Part 1

The First Explosion of the PNFAS

When Adriana arrived at the PNFAS in September 2016, the 23-year-old knew right away that, as an MS13 gang member, she would have to fight.

She was already familiar with the dynamics in the prisons and knew the risks of being a gang-affiliated inmate. She had previously visited incarcerated fellow gang members, including her brother and her husband. The latter was serving his sentence at the Támara National Penitentiary, located less than a kilometer from the PNFAS.

Adriana witnessed firsthand the overcrowding and corruption in the men’s prisons. She knew that several sections of these facilities were completely run by gangs, who found ways to smuggle in weapons and other contraband. And although confrontations were common between rival groups, she felt reassured knowing that the authorities separated the gangs into their own sections.

So, when her turn came, she felt ready to face these challenges.

But the chaotic situation at the PNFAS was nothing like she had imagined.

The MS13 women were scattered throughout the prison, mixed in with the general population who did not belong to any gang, and also with their Barrio 18 rivals, who made up the majority of the prison population. There were no maximum-security sections, so a woman imprisoned for a minor crime could share a cell with another accused of multiple homicides and organized crime.

In addition, a few months after Adriana’s arrival, authorities transferred several leaders of both gangs from the San Pedro Sula prison, which had been shut down due to problems of violence and corruption.

Thus, the PNFAS became the sole women-only prison in the country.

SEE ALSO: Where Chaos Reigns: Inside the San Pedro Sula Prison

This created an environment of constant altercations, threats, insults, and aggression between the two gangs. As a minority, the women associated with the MS13 were terrified. And women in the general population lived under constant stress from exposure to the confrontations.

“It was so horrible because those women from [Barrio] 18 would walk outside and beat up [all the inmates],” Adriana said. “They made life impossible.”

“You never knew who you were talking to. We were surrounded by opposing gangs. I lived in fear and anxiety. I couldn’t sleep. It was only a matter of time before something like [the 2020 massacre] happened.”

Lourdes Osorto, imprisoned for drug trafficking and money laundering but not associated with any gang. She was killed with her daughter during the 2023 massacre.

Several inmates from both the MS13 and the general population said they had requested the authorities separate the gangs and house them in specific sections. However, these requests were ignored for years.

Adriana soon understood that she had to protect herself.

During her first few months, she tried to keep a low profile. She did not share many details about her life, avoided answering questions, ignored insults, and did not get into trouble. Nor did she participate in the workshops, courses, or trainings offered at the prison, because she did not want the dieciocheras — as Barrio 18 gang members are known — to identify her. She decided to become invisible.

But that did not last long. Tension between the two gangs mounted. Adriana remembers the Barrio 18 members harassing the younger women linked to her gang and those who had just entered the prison.

She decided she had no choice but to take the bull by the horns and assume her identity as an MS13 gang member.

The Feisty One From the Pacific

Adriana grew up on the Pacific coast, near the Nicaraguan border, and spent large parts of her youth in gang-controlled environments.

Some cliques, or cells, of the MS13 operate in this area. But they tend to be overshadowed by drug trafficking organizations and dedicate themselves only to predatory activities like extortion. They do not have the same power as the cliques in Tegucigalpa or San Pedro Sula, which control criminal markets in numerous neighborhoods and even interfere in legal businesses, such as car sales, bars, and transport companies.

It was among these small groups of young delinquents on the outskirts of her city that Adriana found a family. They welcomed her despite her aggressive and hostile personality, which was rejected in other environments.

“I was very feisty. I was too aggressive and too easily provoked. If someone offended me I would insult them and hit them,” Adriana told InSight Crime, where she sat on a small plastic chair in Section 1, her elbows resting on her knees and her head resting between her calloused palms.

Initially, Adriana took on the few roles available to her. The majority of women linked to the MS13 in Honduras are not active members, but rather “collaborators.” This is because since the early 2000s, the gang has prohibited women from joining its ranks. Under this dynamic, women may receive payment for the tasks they perform and protection from other criminal groups, but are not formally considered part of the gang.

SEE ALSO: The MS13 Will Never Be a Gang for Women

However, there are exceptions to this rule. In Adriana’s case, she was responsible for running “errands” like collecting extortion money, distributing drugs, or sending messages. But she never found satisfaction in this work. She knew she could do more. So after more than ten years of collaborating and “working” for them, Adriana officially asked to become part of the barrio, the term used by the MS13 to refer to the gang.

Prior to the ban on female gang members, it was common for female aspirants to choose how they would “jump” or be initiated into the gang. The first option involved being penetrated by several men. The second option was the same ritual followed by male aspirants: enduring a 13-second beating. Within the gang’s patriarchal culture, choosing the second option conferred greater value and respect.

In Adriana’s case, she said the local bosses only asked her to carry out a “mission.” She did not specify what this was, but generally this refers to committing a murder to prove her worth.

Determined, Adriana followed through. She managed to break the gender barrier and become an active part of the gang. She felt empowered and finally valued by that world of men.

But her new role was short-lived. Just two weeks after her initiation, she was arrested for extortion.

Violence as Protection

Although Adriana did not know anyone in the PNFAS, belonging to the MS13 guaranteed that she would be welcomed by the group.

The gang functions as a collection of diverse factions united only by shared norms and identities. Adriana identified herself as emeese — as MS13 gang members are known — and that was enough for her peers in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula to recognize her, even if they had never had previous contact.

Adriana stood out for her violent personality, which was appreciated by the gang leaders. In less than a year, she gained their trust and took on the role of “coordinator.”

Her responsibility was to receive women linked to the gang who had recently entered the prison, manage the resources sent by the gang from the outside, and ensure that unity was maintained among the women associated with the MS13.

She also became the gang’s enforcer in the PNFAS — the muscle that protected her colleagues from their rivals, fighting violence with more violence.

“I spent quite a while beating up women. I hit whoever provoked me. With one woman, I broke her face and knocked out a tooth,” Adriana said. She waved her sturdy arms in the air, vividly recounting the story.

As her reputation grew, the Barrio 18 began to identify her and threats soon followed.

“They told me that they were going to kill me, that I would die soon. But I laughed in their face. I would tell them, ‘I live for my barrio and I’ll die for the gang,'” she recalled.

For the next two years, Adriana kept getting into trouble. She imposed her will through beatings, both against her fellow gang members if they disobeyed her and against the Barrio 18 gang members if they insulted her.

Towards the middle of 2019, after being involved in one of these beatings, she was confined by prison authorities to a place known as “La Plancha,” meaning “The Griddle.” It was a small space without light or water, with poor ventilation and little food, where she was locked up for eight months with five other women also punished for misbehavior.

“It was a very bad time. I think my skin even turned yellow,” Adriana said.

Those months were a turning point. After a lifetime of violence, Adriana says she had suffered so much that she vowed to stay out of trouble, distance herself from the gang, and seek a way out of the criminal world. She turned to evangelical Christianity, the most common and accepted way to leave the gang. She hoped to avoid quarrels with her companions. She also hoped that the Barrio 18 would leave her alone and forget about her.

But it was too late. Adriana had a target on her back.

The First Massacre

After La Plancha, Adriana was transferred to Section 2, where she lived mainly with inmates from the general population. At the PNFAS, the sections are small buildings with dormitories, common areas, kitchens, bathrooms, and laundry areas where between 30 and 100 women are held. The PNFAS has a total of 12 sections, among which there is also a maternity ward and an “annex” where high-profile women, such as public officials, are held.

Most of the sections are built in the form of a square, with an open courtyard in the center and small rooms around it. Each dormitory can sleep up to 40 women, in bunk beds, single beds, or mats on the floor.

In Section 2, Adriana met a woman named Yuri, who encouraged her to participate in evangelical activities like worship, prayer, and dancing, with the goal of keeping her away from the gang. Initially, Adriana approached it all with suspicion. It was not something that appealed to her and she considered it a waste of time. But Yuri persisted and Adriana gradually came round.

On a Sunday evening at the end of May 2020, both women had just finished a three-day fast, during which Adriana had asked God to heal her HIV-infected brother. Satisfied with the sacrifice she had made, she was about to go to bed at 6 p.m. when she began to hear a crescendo of sound.

“The offices are burning! Let us out!” several women shouted in desperation from their cells.

A fire had spread through the prison’s administrative area, located at the entrance to the facility. The offices were empty at that time, but the fire was growing, and the screams of the inmates were growing louder. Under lock and key, they had no way to escape.

The police officers on duty left their posts and ran to try to extinguish the fire with the few resources they had at hand: buckets, hoses, water bottles, and some fire extinguishers. They let some inmates out to help them fight the fire while they waited for reinforcements.

The corridors of the prison were deserted and unguarded. The Barrio 18 took the opportunity to open the locks of their cells and unleash an army of women wielding bats, knives, machetes, and ropes. They set off in search of their targets: six women allegedly associated with the MS13. It remains unclear how they managed to get out.

“Chucky’s here! The Beast is here! We’re going to kill you!” the Barrio 18 gang membersshoutedas they walked through the corridors, according to several inmates.

The six targeted women had only been in the prison for a few days and were all under Adriana’s protection.

Several inmates tried to hide them. They braced the small doors and bars of their modules to prevent the gang members from breaking the locks. But they were at a disadvantage. The Barrio 18 members were in the majority and they were armed.

They found all six women. They took three of them to the gym, where they beat them to death with weights in a horrifying episode that, according to several inmates, lasted until the early hours of the morning. They chased two others to Section 1, where they beat and suffocated them to death.

The last victim was in Casa Cuna, the maternity ward for pregnant women and mothers with children up to four years old. There, in front of everyone, a pregnant woman was stabbed to death.

“They tried to hit all the locks with bloody bats. They wanted to kill them all. They were shouting, threatening. All night I heard the screams of the women who were killed. One of them was my friend.”

Maribel, MS13 gang member, recalls what she witnessed during the 2020 massacre.

Adriana felt the urge to come to the rescue, especially when she learned that the violence had reached Casa Cuna. She wanted to at least save the children.

But it was too risky. The Barrio 18 gang members were already shouting her name and demanding to know her whereabouts.

“Where is Adriana? Bring us Adriana!” she remembers them shouting.

Adriana reacted quickly. She looked for the most secluded place in Section 2 and took refuge in a bed in a dark room. She grabbed all the blankets she could find, pulled herself into a fetal position, and covered herself with them. She tried to hold her breath.

Throughout the night, she remained motionless as she listened to the cries and pleas of her friends. She didn’t even want to cry. She was afraid of making noise and being found. But in her mind, she kept praying. Again and again, she repeated the prayers, hoping with all her might that the gang members would never reach the dormitory.

The episode lasted all night. According to several inmates, the authorities only intervened when it was already over.

Twelve hours had passed when Adriana left her shelter, when the police arrived to examine the crime scenes around 6 a.m. The prison was in chaos and Adriana remembers the smell of blood permeating the air.

She walked frantically through the congested corridors in search of information and to identify the victims. Her tall stature allowed her to see over the crowd to look for her companions. In the midst of the melee, she crossed paths with a Barrio 18 gang member who discreetly showed her a knife.

“We are going to chop you upyou with this. But not right now. Later,” Adriana’s recalls the rival gang member saying.

Sweeping the Problem Under the Rug

When the authorities gave statements to the media, they maintained that this was an unprecedented event and that it was unusual for such violence to occur in a space inhabited exclusively by women.

“This is not normal. Most of them are a passive population, focused on their studies and courses,” National Penitentiary Institute spokesperson Digna Aguilar told InSight Crime the day after the massacre.

Outside the prison, relatives of the inmates protested that the authorities already knew about the threats from the Barrio 18, and demanded that all the MS13 women be transferred to a separate section.

Officials started to rethink the security strategy, and they began to adopt some of the methods used in male prisons.

First, prison authorities temporarily transferred all women openly associated with the MS13, including Adriana, to the maximum-security prison of El Porvenir, in the department of Francisco Morazán, just over 50 kilometers north of the PNFAS. Six months later, they were transferred back to the PNFAS and held in Section 1, along with all those inmates who could in any way be associated with the gang. This included women who simply came from a neighborhood where the MS13 operated, even if they had never collaborated with the gang.

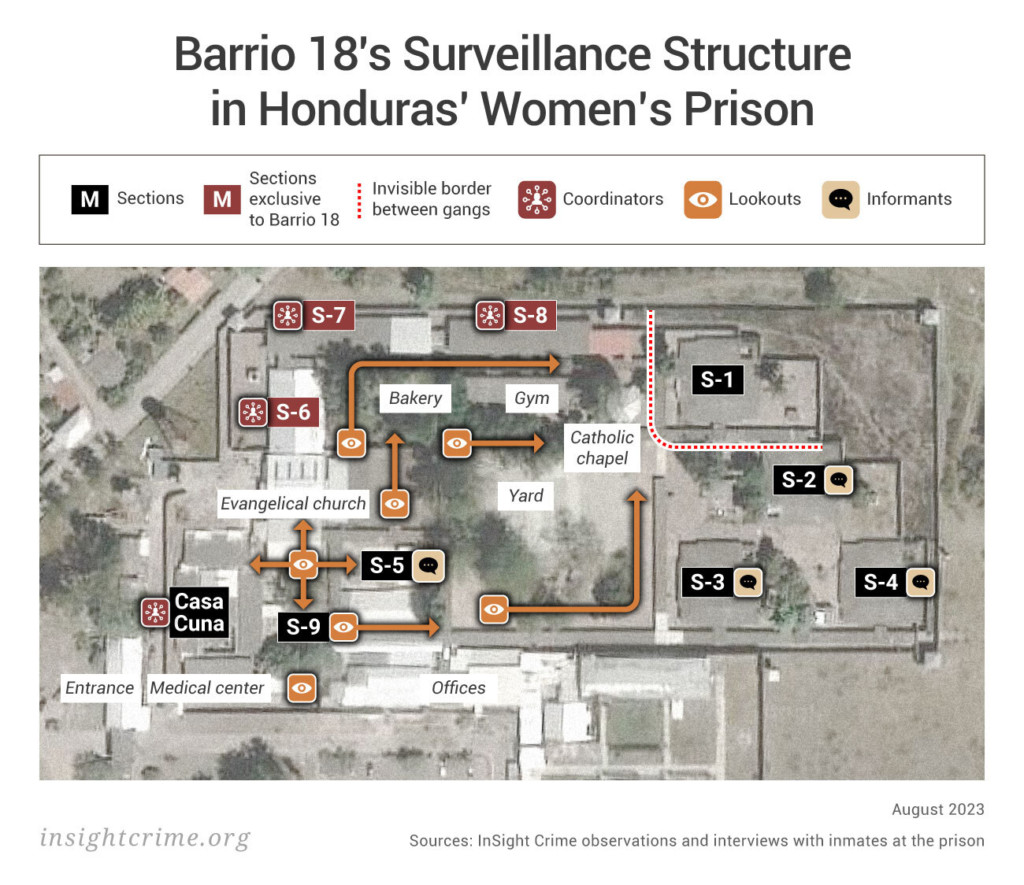

Authorities assured them that they would avoid any contact with the women of Barrio 18, whose leaders and members were held in sections 6, 7, and 8, at the other end of the prison (see map below). In addition, recreational activities, workshops, and social events were reduced. There were plans to build a maximum security module, but they never materialized.

The changes left the PNFAS clearly divided, with most of the territory under the influence of the Barrio 18, including the central yard, the chapels, the health services, the classrooms, the maternity ward, and the area around the administrative offices. The MS13 women could no longer access these spaces, as they ran the risk of being attacked by their rivals.

The authorities were fully aware of this invisible border and even reinforced it.

“They [MS13] can’t come here because this is the territory of the others [Barrio 18],” a prison guard told InSight Crime in front of the evangelical church.

Authorities believed separating the gangs eliminated any cause for concern. The situation seemed to be under control and the gang members had no reason to cross paths in the corridors. Even medical appointments had specific schedules for each group, and the women of the MS13 could only get emergency treatment.

“Yes, [the massacre] was a horrible event. But the gangs are separated now. All of the MS13 was locked up in Section 1 so there is no conflict with the 18,” a prison worker, whom we are keeping anonymous for security reasons, told InSight Crime in April 2023.

Adriana and 100 other women that the authorities associated with the MS13 were now living packed together in one overcrowded section, unable to leave under any circumstances. Although several withdrew from the gang, this did not necessarily imply renouncing that identity. Having witnessed a massacre against their own women reinforced their sense of belonging and fueled their hatred for the Barrio 18.

Section 1 survivors in a temporary home after the 2023 massacre. Credit: Source from Honduras National Penitentiary Institute, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons.

Three years later, in April 2023, the tension was still mounting and the trauma of the massacre persisted. Adriana tried to distract herself from her fears by giving evangelical dance classes in the module and participating in any religious activity that came up. But the threat made by the Barrio 18 gang member kept ringing in her head.

Weeks later, her fears would be confirmed.

Part 2

Pawns in a Wider War: The Barrio 18’s Dominance in the PNFAS

On a Wednesday afternoon in mid-April 2023, Sonia** was sitting behind the bars of the only door that connects the Casa Cuna maternity ward with the corridors of the PNFAS. She had been there since 6 a.m.

Sonia, a member of the Barrio 18, had been incarcerated for barely half a year in Casa Cuna with her seven-month-old son. Her eyes, ringed with black eyeliner, were firmly fixed between the gaps in the bars. She did not miss a single detail of what was happening in front of her. She cautiously watched the prison guards walking by and the inmates being escorted to the doctor’s office. In a lined notebook, she meticulously recorded her observations.

That week was particularly tense. Just three days earlier, her fellow Barrio 18 members had been attacked inside several of the country’s men’s prisons by the MS13. The attack came as a heavy blow to the Barrio 18, and gang leaders felt it was necessary to prevent another setback so they could eventually take revenge.

The PNFAS became the next battleground for the two sides. Here, unlike in the men’s prisons, the Barrio 18 had a clear advantage. The gang members had numerical superiority over their rivals and through intimidation and threats had managed to establish a regime of control and surveillance over the prison.

Sonia had a crucial role to play in sustaining this dominance: she had to maintain order in her section, monitor the corridor, gather information, and report any suspicious activity or people to her superiors.

The day was quite busy, because on Wednesdays the mothers in Casa Cuna receive food, personal hygiene items, clothes, sheets, and other products that family members send from outside. Sonia and the other inmates were waiting expectantly for diapers, baby formula, and medications sent by the leaders of the Barrio 18.

The authorities claim they intensified their vigilance over these shipments after the 2020 massacre, which the Barrio 18 gang members carried out with weapons brought in from outside. They completely empty all the packages and bags that come in, sort them, and then take them directly to the sections where the recipients live. The inmates are not allowed to go out to receive them, as they are forbidden to leave their sections and walk around the prison without being escorted. The corridors are supposed to be empty and the women are supposed to be under lock and key.

However, when InSight Crime visited the prison, about ten inmates of the Barrio 18 seemed to be exempt from this rule. They walked unrestricted and unaccompanied. They gathered in the courtyard and approached the entrances of each section to talk to the inmates in charge of logistics within those spaces. They demanded to inspect all the products that each of them received. The prison guards stood a few meters away from the gang members, at their guard posts, but they did not intervene.

When they came to Sonia, they whispered something in her ear and handed her some papers with notes on them. Sonia nodded, tore out the sheets she had recently written in her notebook and passed the pages to them through the bars. An exchange of information.

The women withdrew and continued their search.

“I have to check absolutely everything that is going on today. Open all the boxes and all the packaging. We never know if those women [from the MS13] are sending us something dangerous or want to do something to us or our children,” Sonia explained, as she struggled to move boxes full of products that were almost half her size.

Seeking Empowerment

Sonia did not always like the Barrio 18. In fact, as a child growing up on the outskirts of Tegucigalpa, she hated the gang members extorting money from her family and acquaintances.

“It hurt me a lot. I didn’t understand why they were doing it,” she said.

But for Sonia and many other young people in Honduras, associating with the gang was a form of survival. In her case, it was also a way to empower herself and gain freedom.

The story Sonia told InSight Crime story is full of economic deprivation, oppression, and gender-based violence. At the age of 14, she became pregnant for the first time by a man a decade older than her, who was possessive, jealous, and abusive. Without finishing school and without the opportunity to develop a career, she was practically held captive for seven years by her abuser, with whom she had another daughter.

Sonia had a few temporary jobs, but she never earned enough to become independent. Nor did she have a support network to help her get out of the abusive relationship. She lived in fear for years, trying to protect herself and her two daughters from her partner’s violent attacks.

SEE ALSO: Q&A: Latin American Children With Parents in Prison Get No Support

In a moment of determination, at the age of 21, she decided to approach the local Barrio 18 cell that operated in her neighborhood. They already knew her. She had lived there since she was a child and had always had to interact in some way with the gang. In the peripheries of large Honduran cities, gang members are often the ones who settle disputes between neighbors, in addition to giving organizations and businesses permission to operate, and collecting extortion money.

Initially, the gang offered Sonia small jobs like drug distribution. This way, she could start earning money and get the protection she needed to emancipate herself.

In a short time, she gained the trust of her superiors and was initiated as a formal member of Barrio 18, eventually leaving her partner. Unlike the MS13, the Barrio 18 still allows women to be part of the gang and assigns them prominent roles. Although Sonia did not mention what rituals she had to follow for her initiation, they are generally similar to those of the MS13: enduring beatings or sexual violence.

Within the gang, Sonia says she was always “multi-purpose.” She worked at whatever tasks the gang leaders asked her to do: contract killings, drug dealing, and against her own convictions, extortion. Although she did not give details about the first two, she said that with extortion she could collect around 8,000 lempiras (approximately $325) a day.

“I think you have to do a bit of everything in this life to get ahead,” she said with a chuckle.

Sonia never used the gang to take revenge on her former partner. However, he was murdered a few months after they separated, in what Sonia says was revenge for the violence he inflicted on his new partner.

“The girl didn’t put up with it and he was killed,” Sonia said.

As the months went by, Sonia had a relationship again, this time with a Barrio 18 gang member. At the age of 23 she became pregnant for the third time. But far from being supportive, the father fled shortly before the birth and left her alone again, with full responsibility for raising her child.

Once again, Sonia had to fend for herself. She never stopped working during her pregnancy, nor did she take time to rest, as her leaders had recommended. The important thing for her was to continue collaborating and generating money to prove that she was still worthy of being part of the gang.

“They told me not to go out, to stop walking around, to go to bed. But I kept going,” she said.

Less than a month after giving birth, Sonia was arrested for extortion and ended up at the PNFAS. Together with her newborn baby, she was assigned to Casa Cuna. Her daughters, aged 10 and three, were left in the care of her ex-partner’s mother.

The Privilege of Belonging to the Dominant Gang

Arriving at the prison was not a bad thing for Sonia.

The Barrio 18 inmates receive constant support from the gang, which puts them in a privileged position with respect to the rest of the population. Sonia frequently received food, medicine and clothing for herself and her baby, something that many inmates did not have access to or did not have the means to obtain.

“Now I know what extortion is for. It is not to feed vices. It’s to support those of us in prison,” she said proudly. “The situation here is not so bad after all.”

In April 2023, there were approximately 915 women incarcerated in the PNFAS, of which around 400 belonged to or collaborated with the Barrio 18, according to then-director Reyna Girón. In comparison, the prison housed just over 120 women associated with the MS13. The rest of the women were part of the general population, who were not associated with either gang.

This numerical superiority of the Barrio 18 is a result of the increasingly participatory roles that this gang has assigned to women. While most women can only rise to the level of collaborators in the MS13 and participate in minor activities, they have more opportunities to grow in the Barrio 18. The women in this gang have been directly involved in handling extortion and carrying out targeted assassinations, making them a target of many operations by the Police Anti-Gang Directorate (Dirección Policial Anti Maras y Pandillas).

The Barrio 18 has been consolidating its dominance in the PNFAS for several years, occupying most of the spaces and acquiring a greater capacity to influence and intimidate the authorities in order to obtain benefits and access resources.

When Sonia arrived at the PNFAS at the end of 2022, the prison had been divided for almost a year as a result of the 2020 massacre. Although the separation was intended to prevent future violence between gangs, the Barrio 18 women had managed to maintain their privileged position, despite being responsible for the tragedy.

While the MS13 women had to isolate themselves in Section 1, which they could not leave for any reason, the authorities assigned three sections to the Barrio 18. The gang members were able to maintain their access to Casa Cuna and the rest of the prison’s common areas. In addition, according to several inmates and what InSight Crime observed in the PNFAS, some gang members were able, through threats or corruption, to obtain permission to leave their sections regularly and walk freely around the prison, something the rest of the population is not allowed to do.

“During my first year working here I was very emotionally affected. I suffered harassment and threats from the inmates. They told me that they were going to tear me to pieces, that they were going to kill my family… They do this to intimidate me and gain benefits.”

PNFAS worker, who is being kept anonymous for security reasons.

But this dominance didn’t give the Barrio 18 gang members complete piece of mind. The possibility that the MS13 could mount a revenge attack kept them vigilant, and they set up a rudimentary surveillance structure.

“We feel reassured, but not safe. We never know when something might happen,” Sonia said.

The inmates interviewed by InSight Crime claimed, for example, that Barrio 18 leaders had set up informants and lookouts in all the general population sections to identify infiltrators or collaborators of the MS13.

In addition, the women who were allowed to leave their sections daily were strategically located in the corridors, near the security filters, in front of the doors of other sections and at the entrance to the prison. Through paper notes, calls on smuggled cell phones, and clandestine visits between different modules, they maintained constant communication among themselves.

This allowed them intimate knowledge of the prison. They learned the prison guards’ every move, and constantly gathered intelligence on their rivals and the rest of the population. When the order to attack arrived, as in May 2020 and June 2023, the gang had identified the location of their victims and knew when there would be less presence of the authorities.

Sonia had a mid-level rank within the gang, which was not enough for her to leave her section. But in addition to guarding the corridor in front of Casa Cuna, she was responsible for authorizing all access to the area, whether it be for inmates, prison guards, administrative personnel, or outside organizations. No one could enter Casa Cuna without Sonia’s permission. It didn’t matter what the authorities thought.

The same was true for the rest of the coordinators of the three sections where the Barrio 18 was held.

“Don’t think it’s easy to mess with us. Our duty here is to protect everyone,” Sonia warned.

Reproducing Patriarchal Hierarchies

Sonia left her watch over the corridor for a few minutes and went into the central courtyard of Casa Cuna. Again, with her notebook in hand, she reviewed the list of names of all the inmates in her section. With a firm, clear voice, she began to hand out orders to a group of women who were ready to get to work. Like her, they were all wearing loose-fitting white T-shirts and black sweatpants.

Raquel swept and mopped the patio, Yolanda did the laundry, Natalia accompanied Sonia to the entrance. Fabiana stayed behind to supervise the children playing on the rusty swings in the middle of the yard. Another woman stayed to prepare lunch. Some of them are gang members, others are Barrio 18 collaborators, and a small number have no association with the gang. In any case, they must obey Sonia.

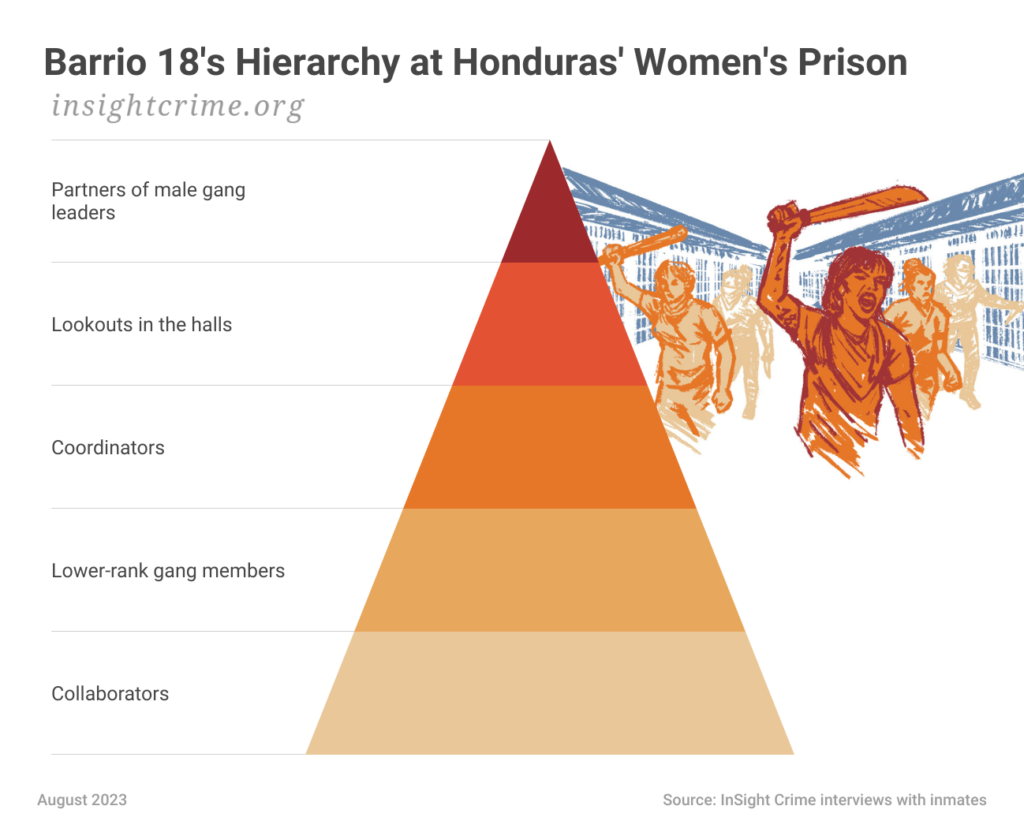

Maintaining discipline is important. The gang cannot dominate a prison without internal order and clear lines of command. That is why the Barrio 18 leaders on the outside and in other prisons established a hierarchy among the women of their gang in the PNFAS. It does not matter that the Barrio 18 women are the ones who dominate the prison on a day-to-day basis. In the general structure of the gang, they are still subordinate and cannot operate or mount attacks without the consent of the male leadership.

The level of authority they can achieve depends on the relationship each woman has with the men in the gang, according to multiple testimonies from Barrio 18 members and collaborators. As in the case of the women of the MS13, the top leadership of the dieciocheras in the prison is made up of the partners of the leaders. They have the greatest decision-making capacity and enact the orders that come from the outside. They did not acquire this power because of their personality or their ability to lead or administer, nor because of their criminal history. They acquired it because of the value given to them by men.

Below them, there are women like the ones who walk the corridors, who keep watch and focus on maintaining the gang’s rules. Then there are women like Sonia and those who infiltrate other modules. They are in charge of maintaining order and discipline within those spaces and making sure there are no MS13 infiltrators.

Sonia was chosen by the gang for this role because of her ability and because she had shown her loyalty and leadership capacity. However, she will never be able to grow in the structure, unless she “gets together” with one of the male leaders.

Below Sonia, there are gang members who have been in the group for fewer years and who have only done menial jobs. And, at the bottom of the pyramid, there are the women who have only collaborated with the gang, without being part of it.

This entire structure is maintained through the same mechanisms used to exert control over the rest of the inmates: intimidation, threats and physical violence, such as beatings.

If the Barrio 18 gang members disobey the rules, their own leaders impose punishments. And just like on the outside, if a gang member disobeys or betrays the gang, in the PNFAS these punishments have even resulted in death.

“All the gang members are the same. Here we all receive the same treatment,” Sonia said.

“We can’t misbehave.”

A Permanent Debt

Being part of the Barrio 18 implies a lifelong debt. The options for leaving the gang are extremely limited: flee the country, convert to evangelical Christianity, or die. Sonia has chosen to continue with the gang.

“It seems unfair to me to seek God only when you want to get out. I have never really regretted who I am,” she said.

That, however, does not just mean that the gang members must not violate the rules, but also that they must pay for all the favors and privileges they receive as “they are not free,” according to Sonia. During her time in prison, and even when she gets out, Sonia must work for the gang and obey their rules and orders.

“They always tell us not to get uppity, we have to keep working,” she said.

The leaders’ orders also involve violence, including killing their rivals. Sonia and her companions are ultimately mere pawns.

On June 20, 2023, after several weeks of monitoring, gathering, and planning, the Barrio 18 women finally received the order to attack from the ringleaders on the outside, according to intelligence documents obtained by Honduran media outlet Contracorriente. The date was confirmed to InSight Crime by a source at the National Penitentiary Institute on condition of anonymity because she was not authorized to speak on the subject.

The instruction was clear: get out, burn Section 1, and kill the emeese.

The whole system of surveillance, gathering of intelligence, and maintaining order and discipline among its members had prepared the Barrio 18 women for this tragic moment.

Part 3

Authorities View Violence With Denial and Indifference

In mid-April 2023, two months before the massacre, the then-director of the PNFAS Reyna Girón remained calm in her office as she continued with her daily activities. With a stiff, almost military demeanor, she received the penitentiary police, service providers, and other visitors to the prison, including the InSight Crime team.

Girón had only been the PNFAS director for a few months and it was her first time working in a prison after a long career in the Honduran National Police. She had come to replace former director Érika Rodríguez, who was dismissed at the end of 2022 after being accused of improperly granting benefits to some inmates.

With deep enthusiasm, Girón spoke about her plans to make the PNFAS a model prison, where inmates could receive professional training, develop their artistic skills, and eventually acquire the necessary tools to reintegrate into society.

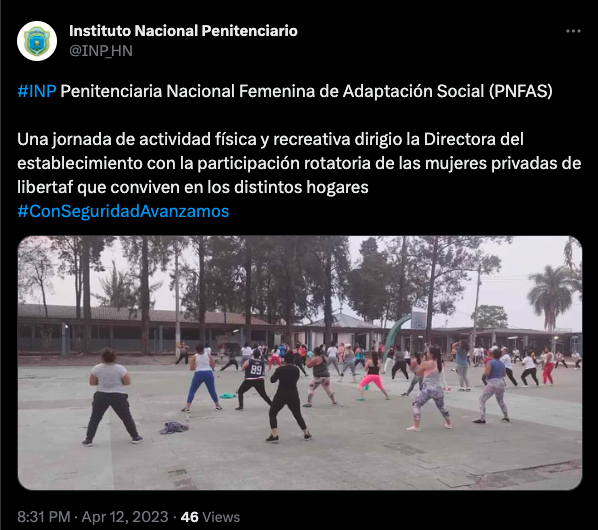

She was proud of some changes she had already made to improve the women’s experience. For example, she allowed the food menu to be expanded to include more nutritious options, established Zumba classes to give inmates an hour of recreation, reinstated conjugal visits, and had an open-door policy in her office.

But the subject of gang violence seemed to be taboo for the now-former director. While the rest of the administrative staff and the inmates who witnessed the first massacre in 2020 talked about it openly, Girón was quick to evade the subject. On the possibility of future violence, the she stated that it was unlikely to happen, as the gangs were separated and any possible problems could be solved by “talking to them.”

“I won’t deny that there is fear. But the situation here is very well controlled. I tell [the inmates] not to make things up. We have no knowledge that anything [violent] could happen here,” she told InSight Crime.

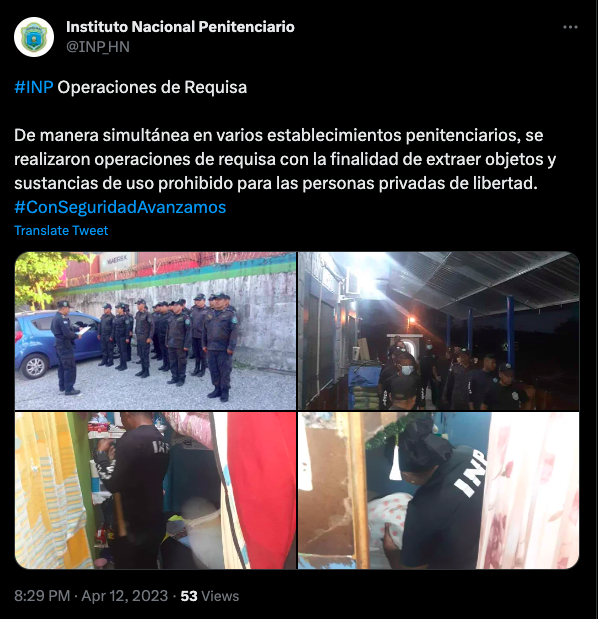

This evasive posture also seemed to be reproduced in the communications of the National Penitentiary Institute. On its Twitter account and its official webpage, the institution constantly reported on violent events and searches in male prisons, while the PNFAS only reported on recreational activities. It never addressed issues related to violence or the presence of criminal structures.

On the left, a post by Honduras’ National Penitentiary Institute about a series of security operations in male prisons on April 12, 2023. On the right, a post about a Zumba class at the PNFAS, on the same date.

However, for the PNFAS inmates and the prison employees working under Girón, the threat was imminent.

Constant Fear

Six days prior to Giron’s interview with InSight Crime, a series of clashes between the MS13 and the Barrio 18 had broken out in various men’s prisons across the country, leading to deaths and injuries. According to according to some media outlets, these were allegedly attacks by the MS13 to gain the upper hand over the Barrio 18.

For many inmates, this was a clear warning sign that these confrontations could spread to the PNFAS, where the Barrio 18 could retaliate.

“We are very afraid of something like that happening here as well. Of course, that is a possibility,” a former Barrio 18 collaborator, who is now part of a Christian group and asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, told InSight Crime.

These fears also affected the administrative staff, who came to the prison on a daily basis and were in constant contact with the inmates.

“I am very stressed by what happened [in the men’s prisons]. We are all at risk here because we have women from opposing criminal structures,” a female prison employee, who is being kept anonymous for security reasons, told InSight Crime.

The tension between the two gangs was evident. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights had even published a report at the end of April 2023 in which it warned that the Barrio 18 was dominating the rest of the inmates, especially the women of the MS13, who felt threatened.

However, the Honduran authorities were focused on intervening in the men’s prisons, searching every corner of the prisons, suspending all visits and dismissing whoever was necessary.

Meanwhile, the PNFAS was excluded from this strategy, once again leaving women in the background.

SEE ALSO: Honduras Makes Few Advances Against Crime During 6-Month State of Exception

In the absence of certainty on the part of the authorities and their constant denial of the problem of violence, many PNFAS women decided to take their own measures to try to protect themselves, as they had always done.

Inmates in the general population, for example, tried to keep a low profile, avoiding eye contact with Barrio 18 gang members and limiting their communication with them. Those who were part of the evangelical church took refuge in religious activities to keep away from any conflict that might arise.

“There is no other option. There is an atmosphere of constant anxiety here,” Yohana Midence, a general population inmate who was later killed during the June 2023 massacre, told InSight Crime.

Adriana and the women in Section 1 were looking for ways to protect themselves, since the MS13 had warned them from the outside to be alert. The coordinator of the section forbade them to leave the section for any reason, and worked to maintain order and discipline to avoid internal fights that would leave them even more vulnerable. Other MS13 women were constantly planning what to do in case of an emergency and desperately trying to convince the authorities to offer them greater protection.

“I sleep with my shoes on and one eye half open, in case [the Barrio 18] come unexpectedly,” a veteran MS13 gang member, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, told InSight Crime.

Meanwhile, the women of the Barrio 18 were preparing to attack, but also remained alert and defensive. Sonia did not stop guarding Casa Cuna and her companions prowled the corridors all day. One of the Barrio 18 coordinators explicitly stated that her gang would not talk to journalists or members of civil organizations after the riots in the men’s prisons. They did not want to draw attention to themselves.

But when they could, the Barrio 18 memberswould approach the fence of Section 1 to leave threatening notes to their enemies.

“You’re going to die, bitches,” was the threat repeated to them days before the massacre, according to survivors’ accounts compiled by the newspaper El Heraldo.

Tragic Outcome

On the morning of June 20, 2023, a dense curtain of smoke obstructed the view of a small group of residents in the town of Támara. The area is quite dry and fires had been common in recent months. But this fire was different. The villagers immediately recognized that it came from inside the PNFAS.

Amazed, they began to record the incident as they casually continued their conversation and laughed about whatever had happened to them that day.

Suddenly a shot rang out. The laughter died down. Then another. Then a burst of bullets that could only come from a high caliber automatic rifle. Screams could be heard in the distance. The video recording stopped.

Hours later, the news was all over the headlines of the Honduran press and had gone around the world.

A group of women belonging to the Barrio 18 gang managed to break out of their cells, armed with assault rifles, pistols, explosives, and machetes, and allegedly took all the prison police hostage

The gang members ran directly towards Section 1 of the prison, where Adriana and the rest of the women associated with the MS13 were being held. They threw in a burning mattress doused with gasoline, and began firing indiscriminately.

The MS13 women tried desperately to flee, climbing over walls and fences, climbing onto the roof, jumping, and running away. Only some of them succeeded.

Of the 46 inmates who died that day, at least 27 lost their lives in Section 1, which was completely destroyed. Most were trapped in their dormitories and were burned to death. The rest died from bullet wounds.

Adriana was wounded in the leg, possibly from a bullet or machete cut, but she got out and was taken to the hospital.

Another 19 women, who were not gang members, were killed in other areas of the prison.

Authorities eventually claimed they had identified 12 alleged perpetrators associated with the Barrio 18, but so far have not released their names. InSight Crime was unable to confirm whether Sonia was among them.

Outside the prison, dozens of relatives of the inmates remained gathered for hours, desperate to hear news of the identification of bodies. Meanwhile, journalists, human rights defenders, officials, and politicians demanded answers.

In statements to the media, Honduran authorities avoided assuming responsibility and maintained an evasive stance, claiming to have had no knowledge that something like this could happen in the PNFAS. Several Honduran media, such as Contracorriente, later found evidence that there were intelligence reports that warned about the possibility of an attack on Section 1.

The authorities also failed to provide an explanation as to how the high-caliber weapons used in the massacre were brought into the prison or how the Barrio 18 members managed to get out of their cells once again.

InSight Crime made repeated attempts to contact all the authorities in charge of the PNFAS to get their version of events. However, at the time of publication, we had received no response.

Immediately after the massacre, Girón and her entire police team were dismissed. Security Minister Ricardo Sabillón was also removed from his post, and Vice Security Minister Julissa Villanueva was forced to resign from the Commission for the Control of Penitentiaries, which was in charge of maintaining security in the prison system following gang conflicts in the male facilities.

In response, President Xiomara Castro transferred control of the PNFAS and all of the country’s prisons to the armed forces, despite the military’s record of alleged human rights violations when administering these facilities between 2019 and 2022.

In July, authorities began transferring all male gang members to separate prisons. In addition, Castro instructed that a maximum-security prison be built on a group of islands in the Caribbean so that gang members “remain with no communication.”

Once again, however, women have been left out of the equation. So far, the PNFAS gang members have not been transferred to different prisons, nor has the protective infrastructure within the prison been modified. The women associated with the MS13 were only temporarily moved to another area isolated from the rest of the prison.

Without structural changes like these, the threat of future violence in the PNFAS remains.

*This subject’s name and personal information have been modified for security reasons.

**This subject’s name and personal information have been modified for security reasons.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.