“Killed in Action” was the tragic news Lieutenant Joseph “Ed” Carter’s family received from the front. As they would eventually find out, but only after holding a funeral service, Carter was alive and (relatively) well, imprisoned at Stalag Luft III, a German prisoner of war camp that mostly housed airmen.

The sheer number of prisoners of war held during World War II is incomprehensible, with some 35 million military personnel detained by enemy forces throughout the war. Prisoner treatment varied between strict adherence to the Geneva Convention and its provisions all the way through summary execution and torture, depending on the nation, camp, and day.

During his imprisonment, Carter was able to keep a journal, a digitized version of which is available on JSTOR courtesy of Wake Forest University. The journal falls somewhere between a collage, an art project, and a diary.

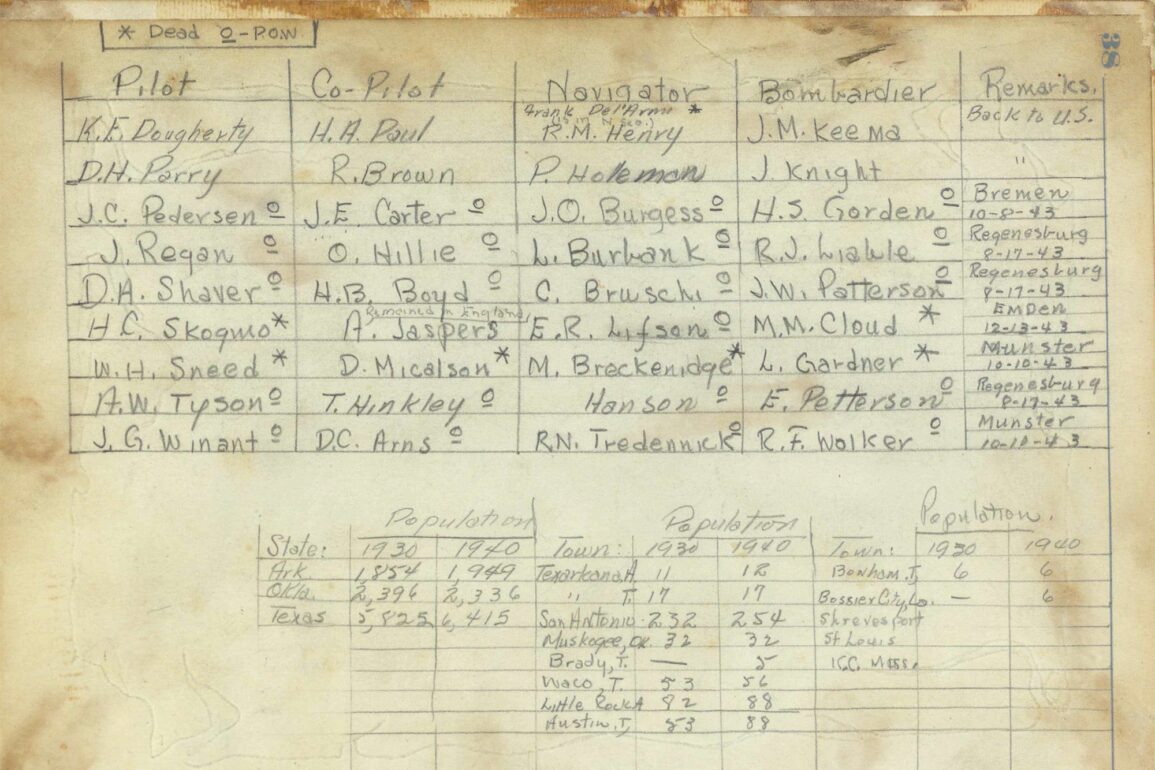

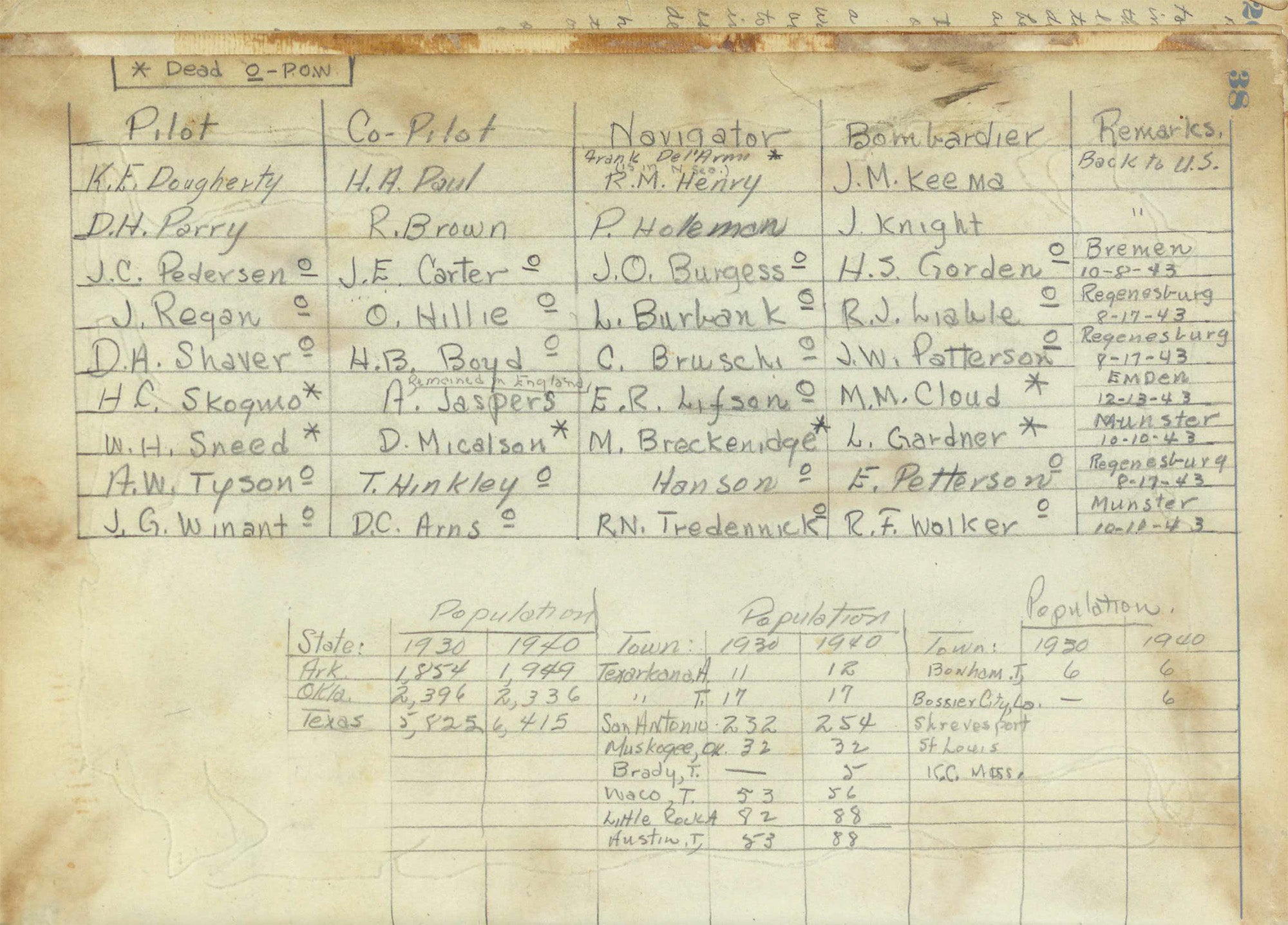

Carter liked lists—the journal is full of them. They’re entertaining and informative, his art skillful. In the list below, he identifies his fellow airmen, their flight assignments, the date and location their aircraft went down, and their life statuses, noting if they were deceased or being held prisoner of war.

During Carter’s incarceration at Stalag Luft III, it became the site of one of the most infamous atrocities committed by the Germans against Allied prisoners. Fifty Royal Air Force airmen were executed after escaping the camp, victims of not only German bullets but a broader tit-for-tat of politicking reprisals using POWs as pawns. Surprisingly, the content of Carter’s journal is missing many of the brutalities one would expect.

Humanitarian aid was flowing freely into the camps, and the contents of Red Cross parcels received from various nations were listed out methodically by Carter. Each prisoner received one of the parcels weekly, plus their German rations as described. Carter’s notations show that sometimes they were reduced to half rations. While the United States, Canada, and Britain sent Spam, New Zealand provided lamb tongue. Only American packages included cigarettes.

It was the duty of the International Red Cross to assure belligerents were following the Geneva Convention, which meant its representatives needed to have access to the camps. Carter’s journal shows that there was some collaboration with outside groups beyond just the supply parcels. He was able to access limited amounts of information and had regular contact with the outside world.

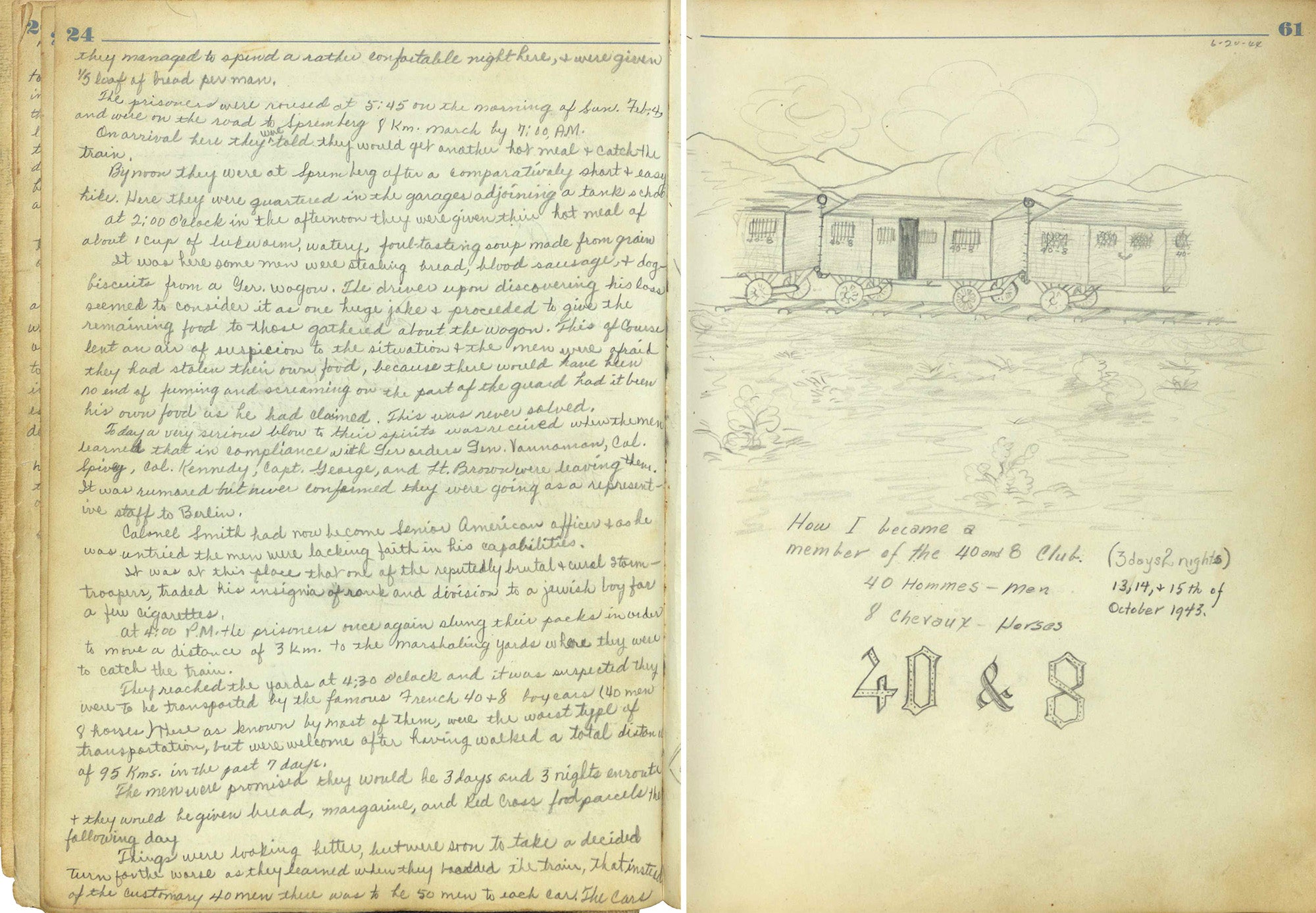

The journey to the camp was arduous, and Carter’s documentation of it displays his characteristic humor. The “40 and 8” club refers to the forty men and eight horses that went into each train car; though in Carter’s case, fifty men or more were crammed in for three long days. Judging by the tone with which he described the incident, it was one of the more harrowing of his experiences.

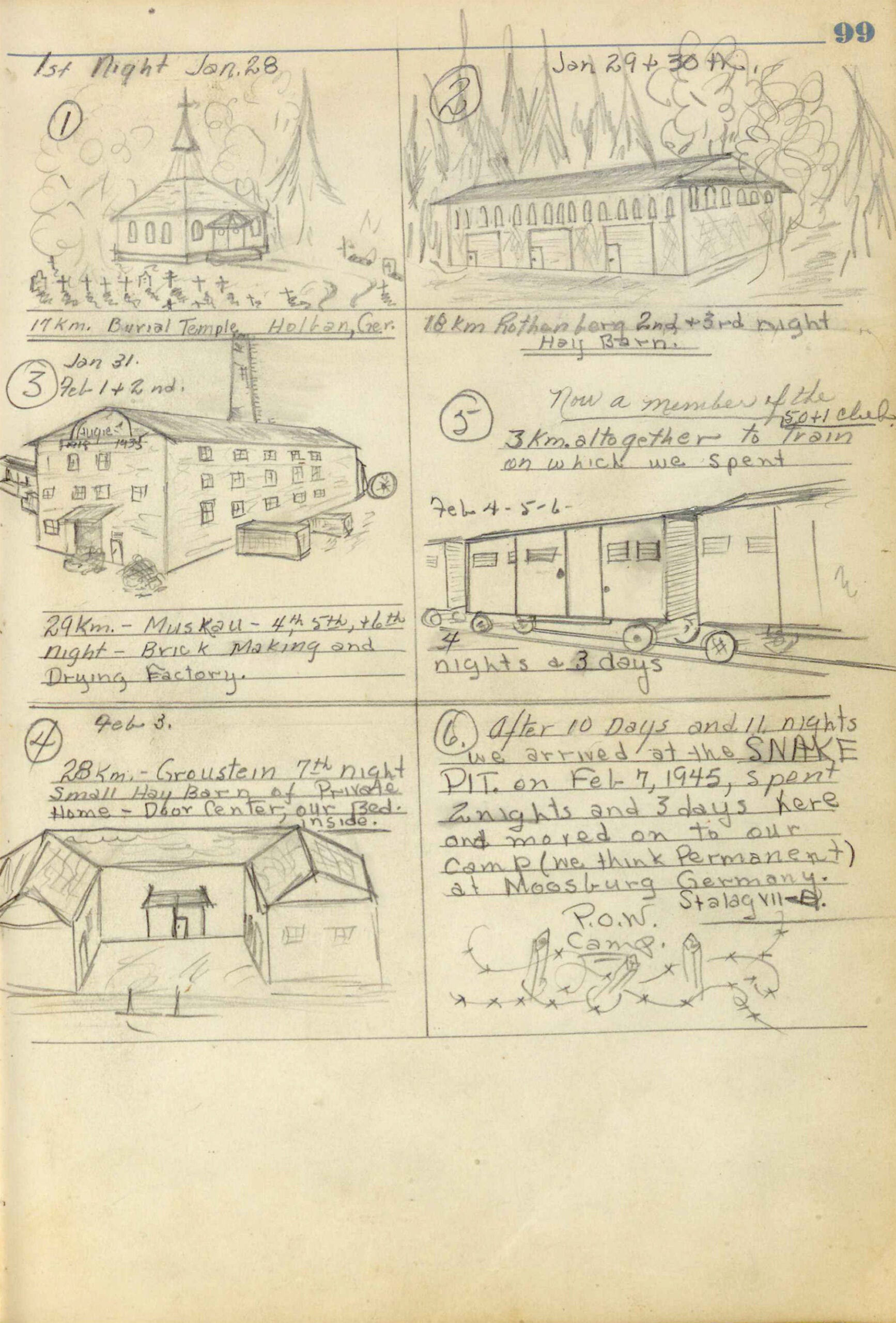

Elsewhere in his diary he writes of the hasty German evacuation of Stalag Luft III as the Russians advanced. The ten-day, eleven-night journey to Stalag Luft VII may have been even worse than the journey to the first camp.

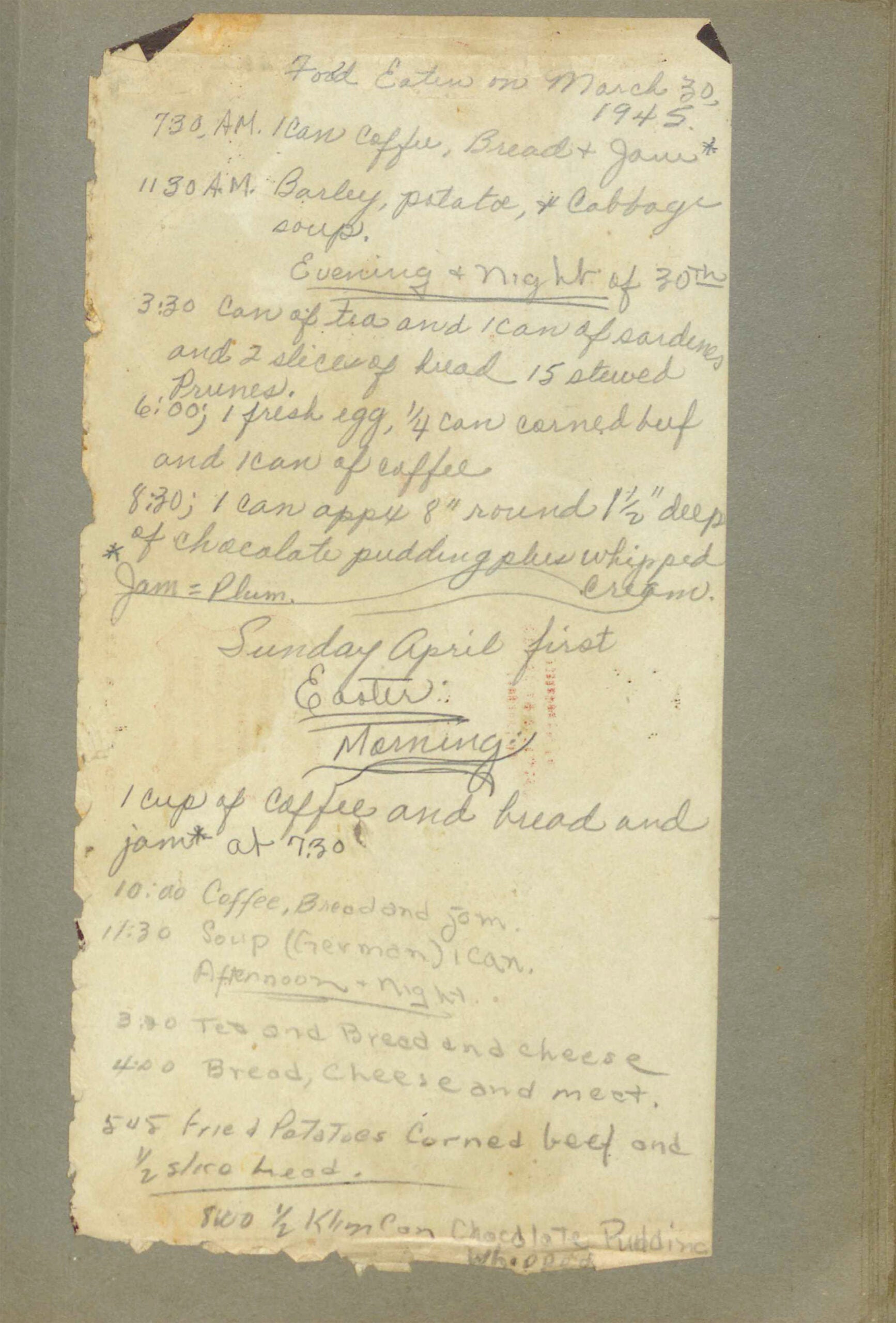

While Jewish people in concentration camps were literally starved, Carter often writes about his daily meals and makes many mentions of food. (The single egg he was given in an eighteenth-month period is forever memorialized in his journal, where he saved the egg shells, as seen in the image at the head of this story.) The following account of the food he ate on March 30, 1945, and Easter Day, April 1, 1945, roughly conveys how much the prisoners were eating. Many, if not most, of his calories came from the parcels provided by the Red Cross and not from their German rations.

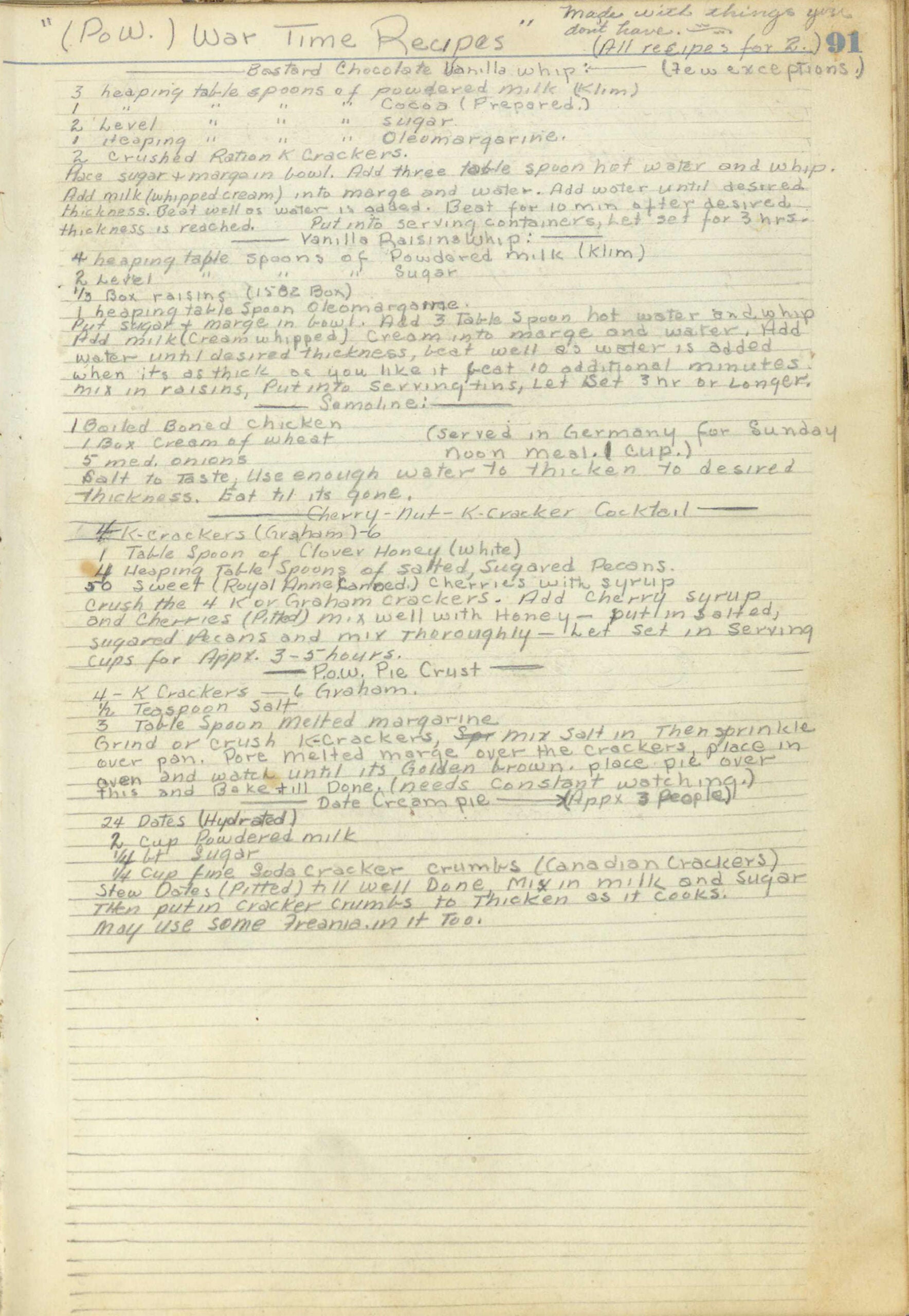

Like people in prison who concoct recipes from items purchased off commissary, Carter and his peers figured out how to produce substitutes of their favorite food items and new favorite recipes using only the things provided by parcels and rations. The men made “P.O.W. Pie Crust” out of graham crackers, salt, and margarine. Their other creations include sweets, a chicken stew called Semoline, and a date cream pie for three.

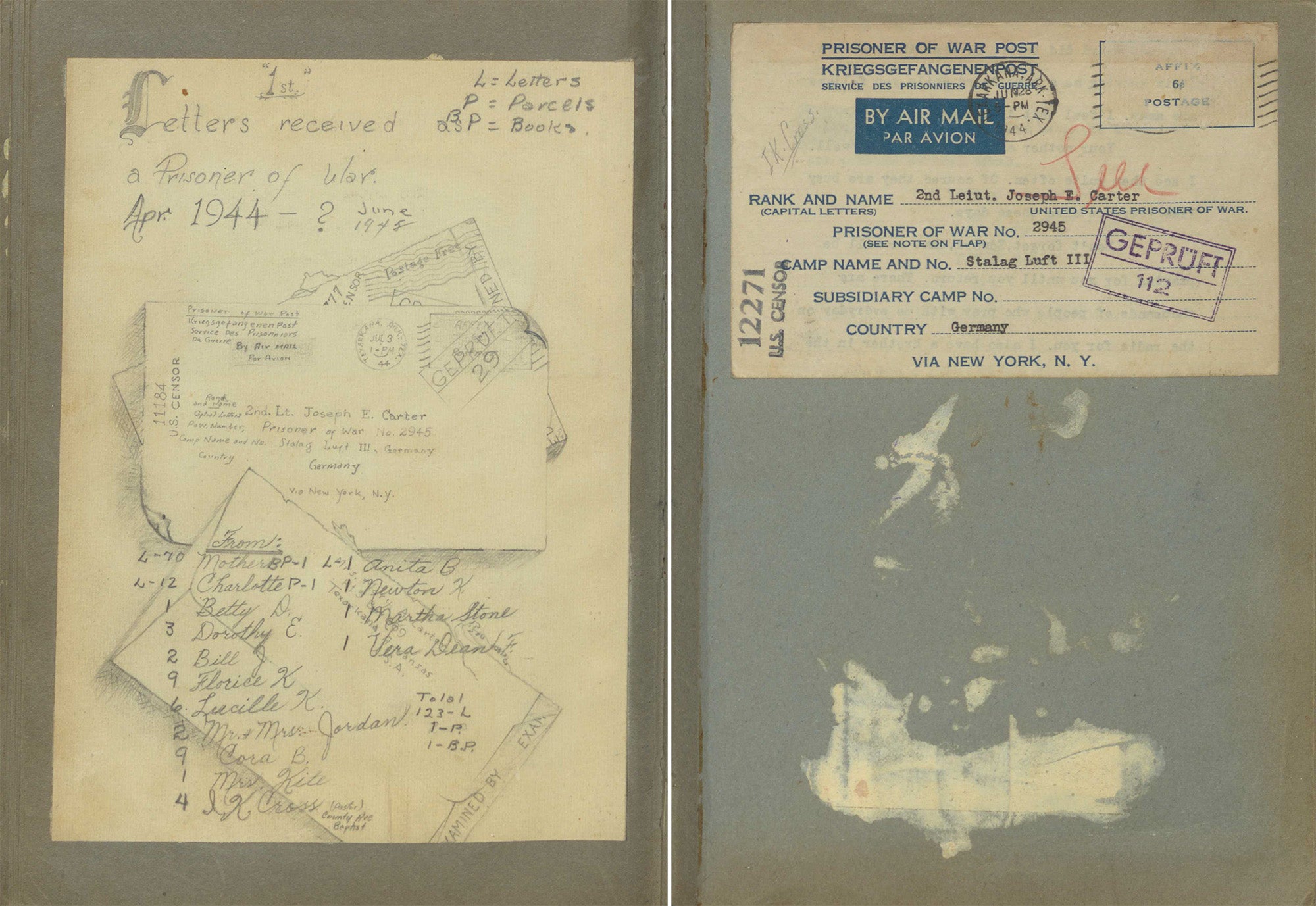

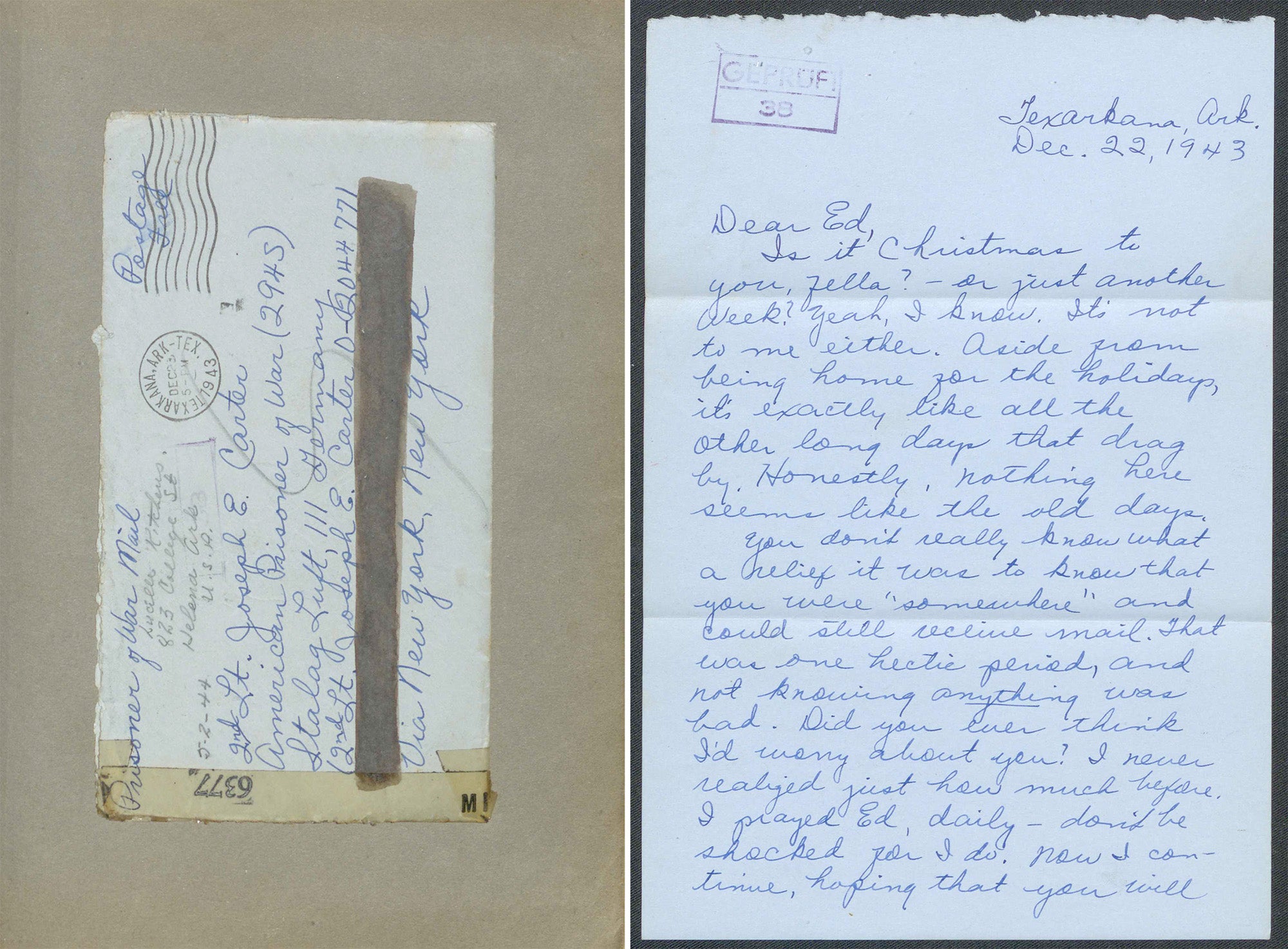

“Prisoner of War Post” had to pass a US censor, but it appears he otherwise had regular contact with his loved ones. Again, he uses his diary to keep track of who sent him what and when.

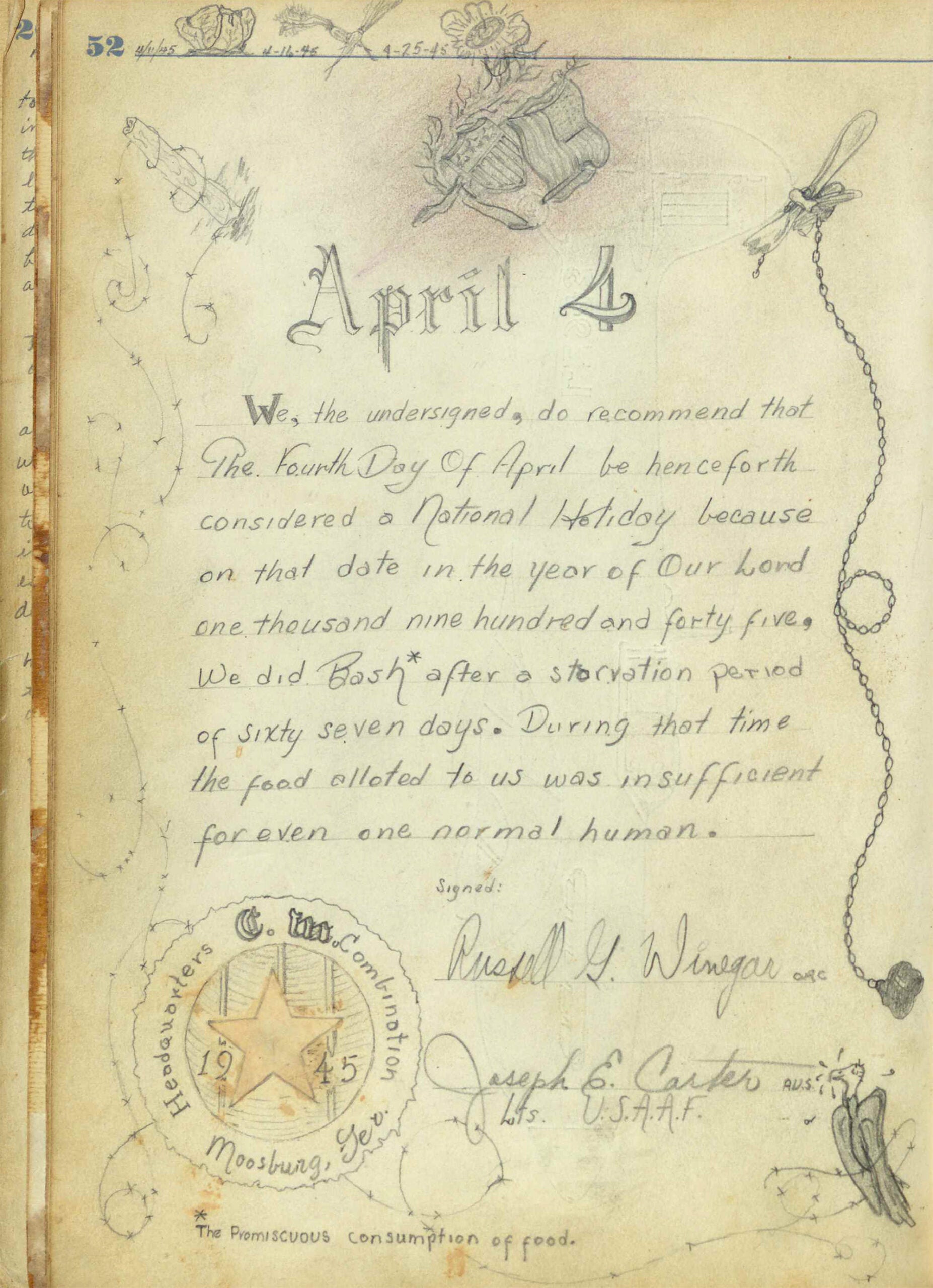

Carter’s sense of humor is evident throughout his diary. “We, the undersigned,” he writes, “do recommend that the Fourth Day of April be henceforth considered a National Holiday because on that date…we did *bash* after a starvation period of sixty seven days.” Apparently, the listed food eaten per days above was perceived as starvation rations by the men.

The period of time where his family thought he was deceased is referred to only euphemistically in letters. “You don’t really know what a relief it was to know that you were ‘somewhere’…”

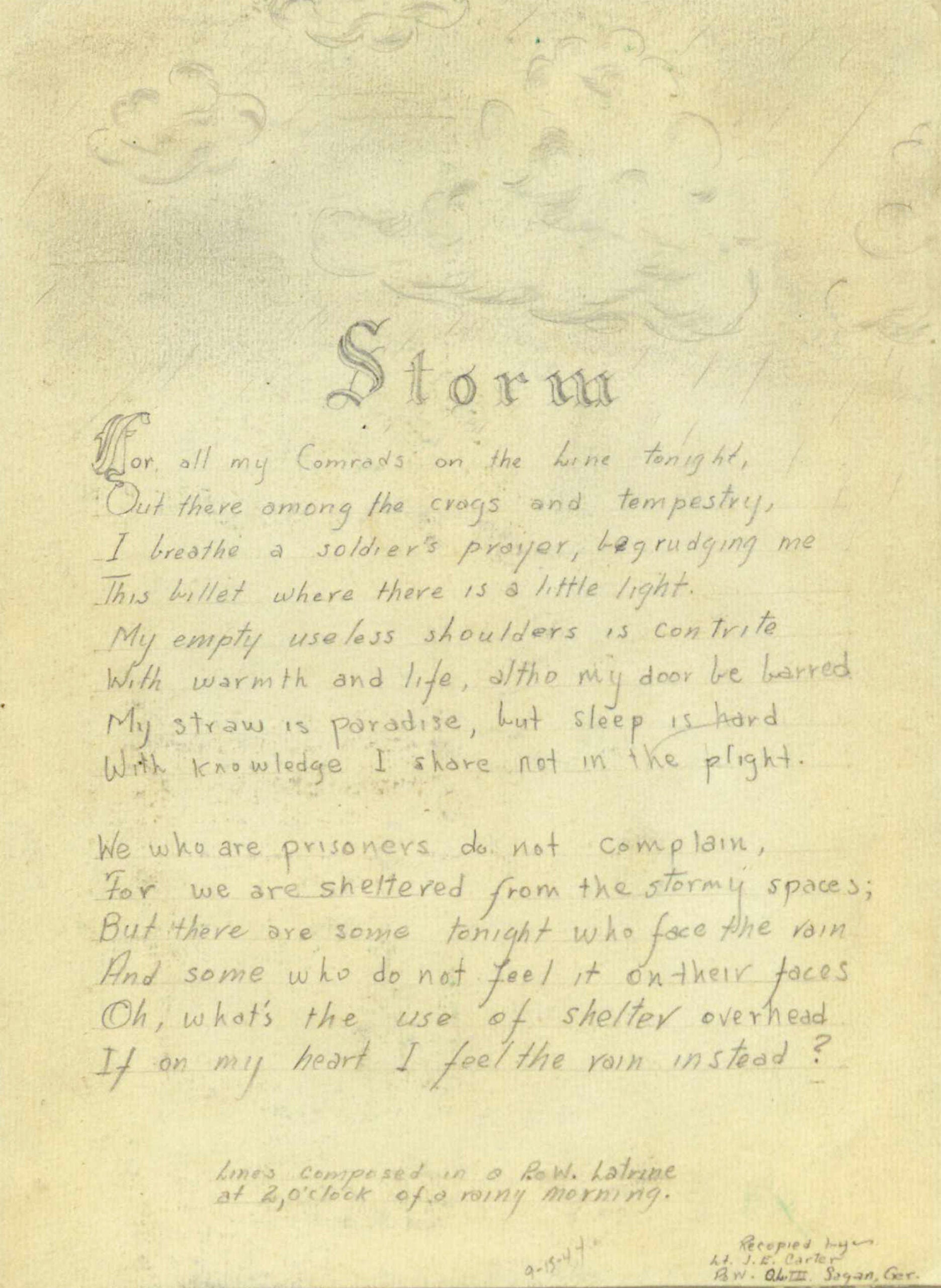

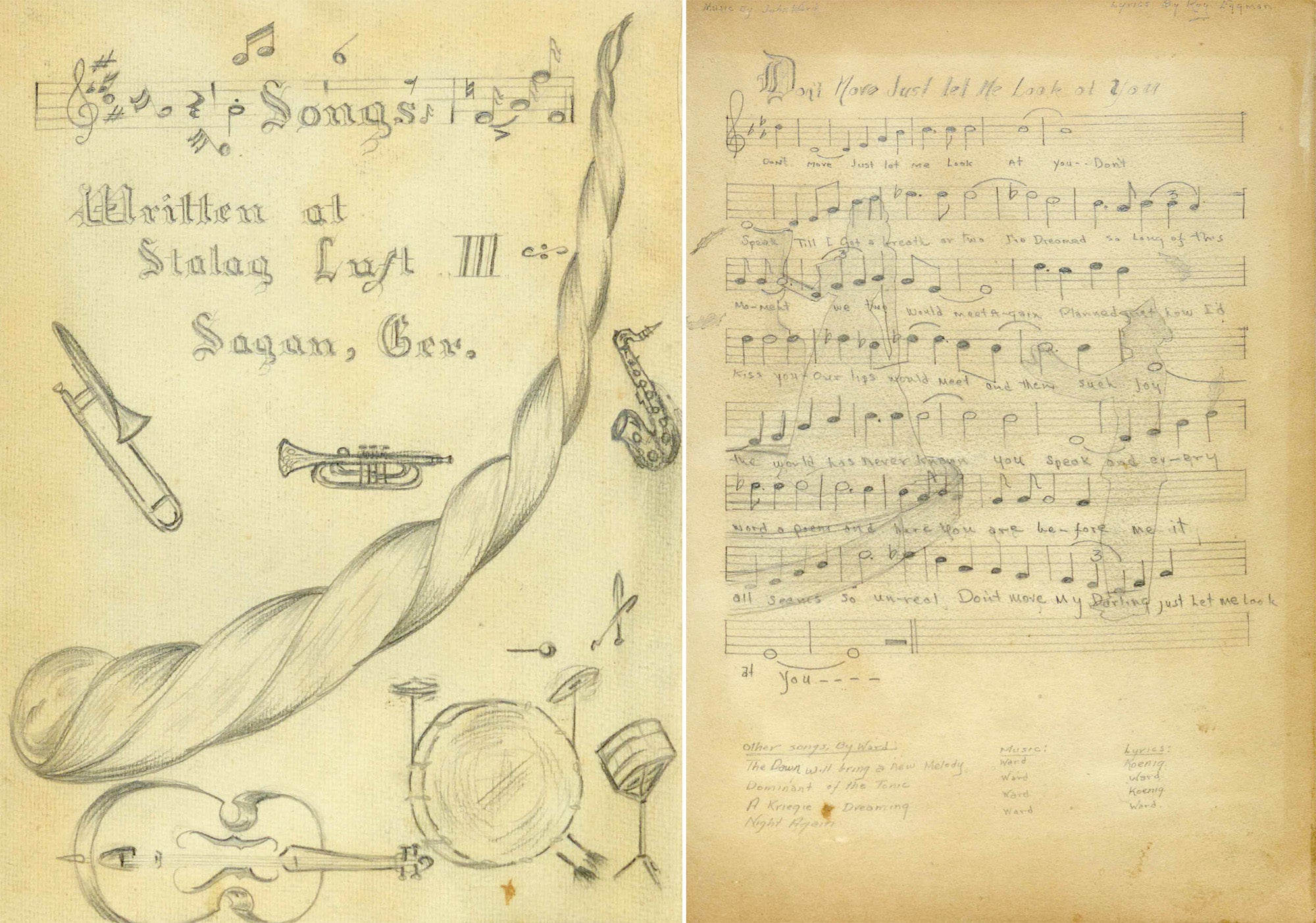

To pass the time, Carter alternated between being an artist, a composer, a poet, and a writer. It’s sometimes unclear when the works are original and when they are copied.

Carter documented the artistic productions of other prisoners of war, with the following music produced by someone named Ward, with other songs’ lyrics written by a Koenig.

Again, in kindred spirit with prisoners everywhere, he had ample time to read and to make methodical lists about what he had read.

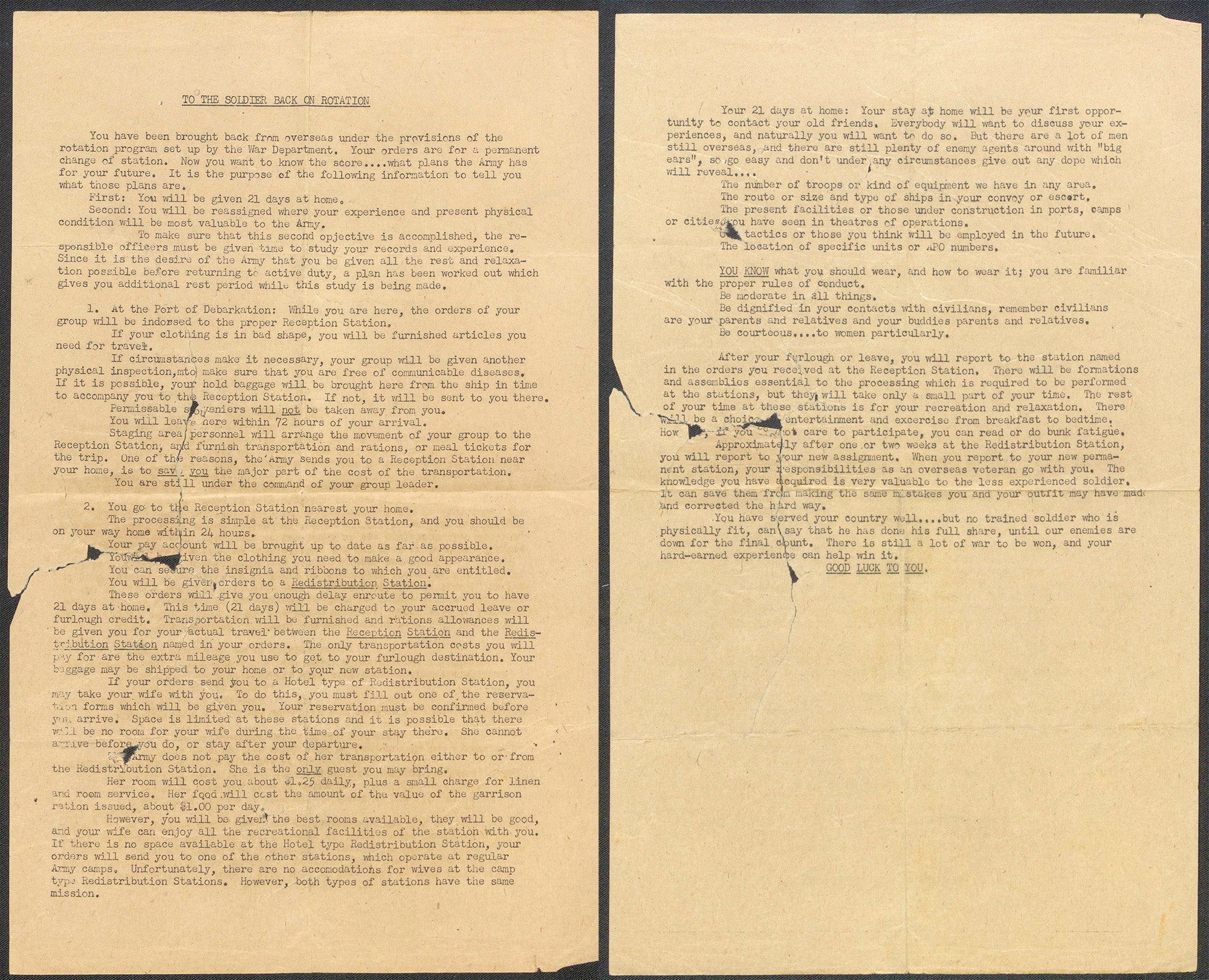

As shown above, Carter documented his hasty transfer to Stalag Luft VII. He later typed up his account and inserted the typed pages into the journal. The dates aren’t always clear, but it appears he continued journaling while in the new camp whence he was rescued, as his Army furlough paperwork can be found alongside other mementos of his return home.

Upon his triumphant homecoming, Lieutenant Joseph “Ed” Carter married his childhood sweetheart. Together, they had four sons. He lived until 2016. Thanks to his creative use of collage and various media, his journal makes for great reading.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.