A Review of the Nation’s Second Look Laws

Second Look For Almost All – Connecticut

In 2021, Connecticut enacted a second look law that is relatively broader than most other states with similar laws. Persons convicted and sentenced after a trial, regardless of the length of their sentence or their age at the time of the offense, can petition the court to review the sentence. The statute also allows the same review of the sentence if it was the result of a guilty plea resulting in a sentence of seven years or less. If the time required to be served was more than seven years, then the state’s attorney must agree to seek review of the sentence. A 2022 revision to the statute clarified that it applies retroactively to all persons sentenced prior to the 2021 law. However, the statute excludes all mandatory sentences from review, which cover approximately 70 crimes.

The sentencing court may, after a hearing and for good cause shown, reduce the sentence. The “good cause” standard gives a court broad discretion in determining when a sentence should be reduced and does not require the consideration of any enumerated factors..))

The court also has discretion whether to hold a hearing. If a hearing is held, the following limitations of subsequent petitions will apply. If the motion is denied, another petition may not be filed until five years has elapsed. However, as of 2023, if the motion was granted in part (which generally means that the sentence was modified but not to the extent that the individual requested), then another petition may not be filed until three years has elapsed. If the motion for a partial sentence reduction was granted in full, the petitioner must wait five years. The right to counsel is not explicit in the statute; however, the public defender services statute provides that a public defender be appointed in “any criminal action,” which has been broadly interpreted to mean “all” or “every.”

Gaylord Salters and Connecticut’s Second Look Law

Salters at Yale Law School in 2023 for a panel discussion on life imprisonment and racial injustice.

Would justice have been better served if Gaylord Salters was required to serve his last six years in prison? That’s the question a judge in Connecticut was required to answer in 2022.

Salters was sentenced to serve 24 years for shooting two individuals at age 21, a conviction that he contests. At the time of the resentencing hearing, he had served 19 years and was 47 years old.

After a lengthy hearing, the judge found that Salters had established “good cause” to reduce his sentence and ordered his release.

In a book he published while in prison, Momma Bear, Salters presents a fictional story, which is a reflection of his own life experiences growing up in public housing during the crack cocaine era and his mother’s experience trying to protect her children. To make ends meet, he and his younger brother mowed lawns and shoveled snow. But when they became old enough to get a job, drugs hit the community where he lived and the jobs were gone. So they resorted to selling drugs.

It was perhaps those choices that caused police to focus on Salters when two men were shot. A significant piece of evidence was the testimony of one of the survivors, who identified Salters as the shooter. But in 2018, that survivor fully recanted and explained that he implicated Salters in order to avoid a mandatory prison sentence.

Salters with Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont in 2022 asking to commit funding for a Clean Slate implementation office that helps

clear lower-level felonies from people’s records.

Prison did not transform Salters’ thinking – he maintained his drive in spite of prison. “I knew what I had to do. They throw people away [in prison]. I was physically locked up. But I would never relinquish my mind.” Salters had four children that he wanted to support while incarcerated. So he started his own publication company, Go Get It Publishing – and began publishing some of his writing. The name Go Get It is his mission statement in life – “It’s up to you to put your best foot forward and do what you have to do in order to get to where you want to be. Period.”

When asked about the others he left behind, Salters explained that there are a lot of productive people in prison who have matured. “You can look at a person’s fingerprint in prison, you can look at their history . . . you can see the signs that are indicative of reform, because they stick out like a sore thumb . . . It’s not the prison. It’s the individual . . . Through that maturation, you will see a lot of individuals who are worthy of that second chance.

Salters credits an entrepreneurial education program run inside of the prison by a local college, Goodwin University, for providing him with support, education, and access to expert assistance to build his company.

In 2021, Connecticut passed a second look law allowing judges to modify sentences without the need for prosecutorial consent. This change opened the door for many, like Salters, to have a judge reconsider their sentences.

At the reconsideration hearing Salters’ son spoke on his father’s behalf: “The things that he has done even while being locked up has shown me how great of a father and a man he would have been if he hadn’t been locked up as well. I just know that with freedom, there is nothing but positive things that will come out of him being outside.”

Since leaving prison, Salters has become a staunch advocate against wrongful convictions and mass incarceration. In 2023, the New Haven Independent announced Salters as its New Havener of the Year for his activism. He is currently teaching a curriculum at a local Boys and Girls Club and wants to develop this program nationwide. He is also working with another local organization to uplift urban communities and is starting his own clothing line.

But for Connecticut’s second look law, Salters would still be in prison today. Typically, even people who are wrongfully convicted have few opportunities to challenge their conviction. Second look laws therefore also expand opportunities for releasing people who are innocent. Salters’ innocence claim does not appear to have affected the judge’s decision. Instead, the judge cited his good prison record, work and educational accomplishments, his publications, and his solid family relationships with his children. Both surviving victims supported his release.

When asked about the others he left behind, Salters explained that there are a lot of productive people in prison who have matured. “You can look at a person’s fingerprint in prison, you can look at their history . . . you can see the signs that are indicative of reform, because they stick out like a sore thumb . . . It’s not the prison. It’s the individual . . . Through that maturation, you will see a lot of individuals who are worthy of that second chance.”

Second Look Reforms for Youth Sentences Beyond JLWOP Reform – Oregon, Delaware, Maryland, Florida, North Dakota, and New Jersey

Before Miller, Oregon Already Provided a Second Look for Sentences beyond JLWOP for All Youth

As early as 1995, Oregon had a second look statute for youth who were convicted as adults to have a judicial review of their sentence after serving half of the sentence imposed. Since that time, the statute has been amended multiple times. Most notably, in 2019, Oregon passed an omnibus criminal justice measure that abolished JLWOP, created new sentence limits for aggravated murder, developed an earlier parole review process for youth, and modified the judicial review of sentence process so it can occur after serving seven and a half years, or half of the sentence, whichever comes first. However, all the 2019 changes are prospective and apply only to sentences imposed on or after January 1, 2020. For all convictions that occurred prior to the 2019 revisions, the statute provides a sentence review for youth for offenses that occurred on or after June 30, 1995, and who received a sentence of at least two years and have served at least half of the sentence imposed. Persons convicted of offenses that occurred prior to June 30, 1995, are ineligible to file a petition. There is an undecided issue of whether a life sentence is eligible for sentence review at the halfway mark of the mandatory term of 30 years.

The court is required to hold a hearing and consider 13 enumerated factors. The petitioner “has the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that the person has been rehabilitated and reformed, and if conditionally released, the person would not be a threat to the safety of the victim, the victim’s family or the community and that the person would comply with the release conditions.” There is a right to counsel. Either party can appeal the decision, but the issues that can be raised on appeal are limited to issues listed in the statute.

Delaware Becomes the First State Post-Miller to Enact a Sentence Review Law for Lengthy Sentences for Youth

In 2013, Delaware abolished JLWOP and passed a retroactive sentence review mechanism for lengthy sentences imposed upon youth.

A person who was under age 18 at the time of the offense and who has served at least 30 years for first-degree murder or 20 years for any other offense may petition the court for a reduced sentence. All mandatory sentences may be reduced. Additional petitions may be filed every five years; however, the court has the discretion to impose a longer wait period between reviews if there is “no reasonable likelihood that the interests of justice will require another hearing within five years.” The court will appoint counsel for an “indigent movant” only in the “exercise of discretion and for good cause shown.” It is within the court’s discretion whether to permit a hearing on the motion.

Maryland Becomes the Second State Post-Miller to Enact a Fully Retroactive Second Look Law for Lengthy Juvenile Sentences

In 2021, Maryland enacted the Juvenile Restoration Act that prohibits judges from imposing the penalty of JLWOP. It also provides that judges are not bound by mandatory penalties and permits persons convicted of offenses committed under the age of 18 and who have served at least 20 years for that conviction to file a request for sentence reduction.

The court is required to hold a hearing and consider multiple factors. The court may reduce the duration of a sentence if it determines that (1) the individual is not a danger to the public and (2) the interests of justice will be better served by a reduced sentence. The language “notwithstanding any other provision of law” grants broad discretion to a court, including reducing mandatory minimums. It was not necessary to explicitly provide a right to counsel in this statute because Maryland is already required to provide legal representation at sentencing, resentencing, and modification hearings. If the court denies or grants in part, a subsequent motion cannot be filed for at least three years. A petitioner may not have more than three petitions considered.

As a result of this law, the Maryland Office of the Public Defender launched the Decarceration Initiative that was designed to provide public defender or pro bono counsel to all persons eligible to file a motion for reduction of sentence under the Juvenile Restoration Act. During the first year of the Act, 36 hearings were held. In 23 of the cases, the courts imposed new sentences that resulted in release from prison. In four cases, the courts granted a reduction of sentence, but additional time in prison was required before release. The remaining nine were denied relief.

Limited Retroactivity: Florida’s Second Look for Lengthy Sentences for Youth

Although Florida has not banned the penalty of JLWOP, the state enacted a review of sentences for certain offenses that were committed by youth after they served 15, 20, or 25 years, depending on the conviction. However, the statute applies to those offenses committed on or after July 1, 2014.

However, in 2015, the Florida Supreme Court held that the statute should apply retroactively to “all juvenile offenders whose sentences are unconstitutional under Miller.” Since then, the Florida appellate courts have gone back and forth on which sentences are de facto life sentences warranting retroactive application of the statute. From 2017 to 2018, there were a number of decisions that held that a term-of-years sentence of more than 20 years warranted judicial review, so all those cases were sent back to the sentencing courts to conduct a sentence review hearing. However, in 2020, the Florida Supreme Court overturned those holdings and clarified a new standard – a young person’s sentence is not unconstitutional under Miller unless it meets the “threshold requirement of being a life sentence or the functional equivalent of a life sentence.” Since that holding, the Florida appellate courts have determined that sentences over 30 years and a life sentence with the possibility of parole after 25 years do not meet the threshold for review. It is to be determined which sentences would warrant review under this new standard.

There is a right to counsel, and the court must hold a hearing, consider several factors, and issue a written decision. Mandatory minimum sentences may be reviewed. If the court determines that the petitioner “has been rehabilitated and is reasonably believed to be fit to reenter society, the court shall modify the sentence and impose a term of probation of at least 5 years.”

Florida permits one review petition for nearly all offenses, except for youth who were sentenced to 20 years or more for a nonhomicide first-degree felony punishable up to a life sentence, in which case, they can have one subsequent review after 10 years.

No Retroactivity: North Dakota’s Second Look for Lengthy Juvenile Sentences

In 2017, North Dakota abolished the penalty of JLWOP and enacted a reconsideration law for those whose offenses occurred prior to the age of 18 after serving at least 20 years for the offense. Despite the statute being silent on the issue of retroactivity, the North Dakota Supreme Court held in 2019 that making the statute retroactive to offenses occurring before the effective date of the statute would infringe on the executive pardoning power. Four years later, the same court reviewed the issue of retroactivity and further found that the legislature did not intend for the statute to be applied retroactively.

When hearings are eventually held on these motions – presumably on or after the year 2037 (approximately 20 years after effective date of statute, when someone would become eligible to file) – courts shall consider a number of enumerated factors and may modify the sentencing, having “determined the defendant is not a danger to the safety of any other individual, and the interests of justice warrant a sentence modification.” Up to three requests for modification can be made no earlier than five years between each decision. The statute is silent as to whether a court must hold a sentence review hearing before making a ruling and whether there is a right to counsel.

New Jersey’s Top Court Creates a Sentence Review Mechanism for Youth

New Jersey is the only state whose highest court was responsible for creating a new judicial review mechanism, as opposed to the legislature. In 2022, the Supreme Court of New Jersey held that certain mandatory sentences imposed on youth violate the state’s constitution. Concerned about waiting for the legislature to act to remedy the issue, the court then declared that youthful defendants may petition the court to review their sentence after serving 20 years. Because there is no statute, there is little guidance on the sentence review process, except that resentencing courts should apply the Miller factors.

Second Look Reforms for Emerging Adults Beyond LWOP Sentences – District of Columbia

The District of Columbia currently has the most expansive age-based second look judicial review statute in the country. The second look law permits an individual to file a reconsideration of sentence if the offense occurred before the individual’s 25th birthday and after 15 years of imprisonment.

The initial version of the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act (IRAA), effective in 2017, provided second look hearings for youth convicted as adults for offenses committed before age 18 and after serving 20 years, who have not yet become eligible for release on parole. But in 2018, the law was amended to reduce the time required to be served from 20 years to 15 years, and struck the provision regarding parole eligibility. It also removed “the nature of the offense” from the factors a court should consider. This change was made in response to the U.S. Attorney’s practice of citing the seriousness of the offense as the basis to deny the motion.) The Omnibus Public Safety and Justice Act of 2020 increased the age eligibility from under 18 to under 25.. See also DC Corrections Information Council (2021, May 19). DC Council Passes Second Look Amendment Act of 2019 [Press release].))

The court may reduce the sentence after considering multiple factors and finding that “the defendant is not a danger to the safety of any person or the community and that the interests of justice warrant a sentence modification.” The court may also reduce a mandatory sentence. A petitioner has three opportunities to pursue an application for sentence review whether the previous petitions were granted or denied, and may apply three years after the last petition. The statute applies retroactively to all prior convictions. The court is required to hold a hearing and issue a written decision. The petitioner is entitled to counsel.

The DC-based Second Look Project has reported that in the six years following IRAA’s enactment in 2017, “approximately 170 people have been released from extreme sentences.” When DC expanded its law to include emerging adults up to age 25 in 2021, over 500 people gained an opportunity for release from such sentences.

Randall McNeil and DC’s Second Look Law

When asked about his favorite childhood memory, Randall McNeil described the times he would visit family in Charlotte, NC and would watch kites flying in an open field. Having grown up in Northeast Washington DC, he had never seen anything like it, and he was instantly captivated. McNeil spent most of his summers looking forward to seeing those colorful kites in the sky.

At the young age of 16, McNeil lost his mother – his primary guardian – and the person that knew and understood him best. A year later, McNeil lost his grandmother and became a father for the first time. McNeil had two more children in the subsequent years.

When McNeil was 20 years old, he was found guilty of multiple charges involving an armed robbery and kidnapping. McNeil was sentenced to 66 years and spent the next 24 years of his life incarcerated at various state and federal institutions before his release from Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) in Cumberland, MD.

As McNeil did his time, he was determined to become the best version of himself in hopes that he would someday be given the opportunity to show the world that despite what he did, he was worthy of redemption. Prior to his incarceration, McNeil earned his GED and recalled that in 2003 while in prison, his perspective about being incarcerated shifted when he began to frequent the prison law library. He described those visits as “going to find the key” to his redemption. It was his source of hope.

He also discovered his ability to positively influence those incarcerated with him. McNeil worked to help shift the mindsets of the men inside and learned that he had a desire to instill hope and value in others despite their circumstances. He went on to become a qualified member of the prison suicide watch team.

McNeil understood that for others to see him as the person he knew himself to be, he would have to constantly put himself in positions to show up as that person. During his time at FCI Cumberland, McNeil worked for Unicor Sign Factory where he was started in a position inputting and receiving orders on a computer. Due to his perseverance and determination, McNeil was quickly promoted to a supervisor.

With the expansion of the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act (IRAA) in 2020, McNeil was finally given an opportunity to petition for his freedom. McNeil was an exemplary candidate. In August 2022, McNeil was granted his freedom with the caveat of five years’ probation—a decision that McNeil desires to have reconsidered. Upon his release, he was finally able to marry Donnetta, the mother of his children, on Valentine’s Day of 2023.

McNeil is grateful to his daughter for providing him with a home in the District of Columbia, one of the requirements for him to be released. He also credits two reentry programs, BreakFree Education and Free Minds Book Club, for helping provide job opportunities and a welcoming community. Through BreakFree Education, McNeil was able to apply for a fellowship at Arnold Ventures, where he is now a full-time employee. His proudest moment has been helping to fund a newly launched nonprofit organization led by another formerly incarcerated person.

McNeil, his daughter Randaisha, and his granddaughters Logan and Dior.

McNeil was not naïve enough to believe that coming home would be easy, but he is honest enough to admit that he did not anticipate just how complex familial and friendship dynamics could be. Free Minds has been an essential part of his life, enabling him to meet weekly with other formerly incarcerated men locally, where they can discuss the challenges of societal reintegration.

When asked about those still incarcerated, he said, “There are a lot of Randalls in there. They all need a second chance. Many of them were arrested after 25.”

Compassionate Release

Federal First Step Act

Enacted in 2018, the First Step Act (FSA) is a bipartisan law that included a wide range of criminal justice reforms in the federal system. One reform was to the law governing the reduction in sentence authority, commonly referred to as “compassionate release.” The FSA amended the law to allow incarcerated people to file compassionate release motions on their own behalf in court. Prior to this reform, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) had the sole authority to recommend release to a court. The BOP rarely recommended compassionate release.

Now, people serving federal prison sentences can file these motions themselves after giving the BOP 30 days to make this recommendation. In the fiscal year 2020, 96% of those granted relief filed their own motion.

In addition to Congress’s change to the compassionate release process, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which is responsible for describing in a policy statement what are extraordinary and compelling reasons for compassionate release, expanded the list in 2023. The prior reasons were limited to medical, geriatric, and extreme family circumstances. Now, additional circumstances include, among others, (1) sexual assault at the hands of BOP personnel; (2) an unusually long sentence in which an intervening change in the law has resulted in a gross disparity between the sentence being served and the sentence that could be imposed today; and (3) any other circumstances or combination of circumstances that are similar in gravity to the listed grounds. There are no exclusions based on the nature of the criminal conviction or length of sentence. No one sentenced prior to 1987 is eligible, whether they are serving a parolable or non-parolable sentence.

There is no right to counsel on these motions; however, a collaborative effort between the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL), FAMM, and the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs has created a clearinghouse program to identify individuals who may qualify for compassionate release and to recruit, train, and support legal pro bono counsel to represent them.

From October 2019 through September 2023, 31,069 compassionate release motions were filed. Of those filed, 4,952 (16%) were granted, and 26,117 (84%) were denied. COVID-19 accelerated use of this law, with most grants of relief (95%) during this period occurring in the second half of the fiscal year 2020. Courts cited the risk of contracting COVID-19 as at least one reason to grant the motion in 72% of the motions granted that fiscal year. However, since its peak in October 2020 with approximately 2,000 decisions recorded that month, filings have steadily decreased with only about 147 decisions recorded in September, 2023.

District of Columbia (60 and Over)

In 2020, the Council of the District of Columbia enacted an emergency COVID-19 response bill, which permitted incarcerated individuals to seek compassionate release from the courts. In 2021, the law was made permanent. Eligibility includes those who are 60 years old and older who have served at least 20 years, those with a terminal illness, or who otherwise present “extraordinary and compelling reasons” that warrant a sentence modification. No other state has a similar judicial sentence review provision based only on elderly age and number of years served.

The court may reduce a sentence if it determines the petitioner “is not a danger to the safety of any other person or the community.” The court must consider approximately 11 outlined factors, but it may not consider factors that have no relevance to present or future dangerousness (e.g., the need for just punishment or general deterrence)..)) The defendant has the burden of proof by a preponderance of the evidence.

Mandatory minimums may be modified. Motions may be filed by the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, the Bureau of Prisons, the United States Parole Commission, or the defendant. As a matter of practice, counsel is routinely provided. The court is not required to hold a hearing to grant or deny a motion.

The District of Columbia Corrections Information Council last reported that from March 2020 through March 16, 2021, 143 individuals were granted compassionate release.

Reviewing the Sentences of Specific Populations – New York, California, and Colorado

New York’s Domestic Violence Survivors Act

Incarcerated people, particularly women, commonly report histories of family or intimate partner violence. Courts typically do not account for when those experiences influence their involvement in crime. A new type of second look law has emerged that focuses on reducing the sentences of these survivors when their victimization was a significant contributing factor to the offense.

New York enacted legislation in 2019 that allows intimate partner and family violence survivors to petition the court for sentence review that is fully retroactive. Most recently in 2024, Oklahoma nearly enacted a similar measure in 2024. In 2016, Illinois enacted a similar law; however, the law includes a two-year statute of limitations to file the petition from the date of conviction, and the law is not retroactive to prior convictions, essentially leaving no remedy for individuals sentenced prior to 2014. Advocates have criticized the lack of meaningful impact of this law. Policymakers in Louisiana, Oregon, and Minnesota have introduced similar reforms.

In New York, a survivor who was sentenced to a minimum or determinate sentence of eight years or more prior to the enactment date of the law may petition for sentence review. Individuals sentenced after the law’s enactment are not eligible for sentence review but can receive a lower sentence if they otherwise qualify for relief. The statute applies to those who are incarcerated or on community supervision but excludes certain crimes, such as aggravated murder, first-degree murder, or any offense that requires an individual to register as having committed a crime of a sexual nature.

The request for sentence review must include “at least two pieces of evidence corroborating the applicant’s claim that he or she was, at the time of the offense, a victim of domestic violence.” If the evidence is submitted with the application, the court is required to hold a hearing. A survivor must demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that at the time of the offense (1) they experienced “substantial physical, sexual, or psychological abuse,” (2) the abuse was a “significant contributing factor to the criminal behavior,” and (3) the sentence imposed in the absence of this mitigation is “unduly harsh.” Interestingly, reviewing appellate courts have the authority and discretion to impose a new sentence if they disagree with the sentencing court’s decision.

As of February 2024, 58 people have been resentenced.

California’s Act for Military Veterans and Service Members

In 2018, California passed a law affecting U.S. military veterans and current U.S. service members who are serving sentences for felony convictions. The law allows qualifying individuals to petition for a recall of sentence and request resentencing if they “may be suffering” from “sexual trauma, traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, or mental health problems as a result of the defendant’s military service,” if not previously considered at the time of sentencing. The court may reduce the term of imprisonment by modifying the sentence “in the interest of justice.”

Individuals convicted after trial, as well as through plea agreements, are eligible to petition for a recall of sentence and request resentencing. The statute applies retroactively.

Not all veterans are eligible to seek relief under this provision – exclusions include those convicted of any serious or violent felony punishable by life imprisonment or death. Because of the statute exclusions, only those serving determinate sentences (a set amount of time to serve) are eligible to seek relief. Approximately 33% of people incarcerated in California are serving indeterminate sentences. The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that in 2016, 8% of all people in state prisons were veterans.

Colorado’s Review for Lengthy Habitual Offender Sentences

In 2023, Colorado enacted a judicial modification opportunity for those convicted under the habitual offender laws who have been sentenced to 24 years or more, and have served at least 10 years, but it applies only to offenses that occur on or after 7/1/2023 (see at Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-1.3-801). Therefore, nobody will be able to apply for a sentence modification until 2033, at the earliest. If the court approves a sentence modification, the new law authorizes the court to resentence the petitioner to a term of at least the midpoint in the aggravated range for the class of felony for which the defendant was convicted, up to a term less than the current sentence. A petition is entitled to appointed counsel and a hearing.

Corrections and Judge-Initiated Resentencing – California

California’s original recall and resentencing law allowed district attorneys (see Prosecutor-Initiated Resentencing section, below) and the Secretary of the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (“corrections”) to file a petition at any time to recommend a reduced sentence for an individual. Effective January 1, 2024, this law was expanded to permit judges to initiate resentencing proceedings if there was a change in the law, which applies to many cases. Incarcerated people do not have the authority under this law to file a petition requesting resentencing – it must be made by the judge, district attorney, or someone from corrections.

When a recall is initiated by a district attorney or a corrections official, “there shall be a presumption favoring recall and resentencing,” which can only be overcome if a court finds the individual currently poses an unreasonable risk of danger to public safety as defined by statute.

Whether initiated by the judge, district attorney, or corrections, the court is required to apply any new sentencing rules or changes in the law that reduced sentences “so as to eliminate disparity of sentences and to prompt uniformity of sentencing.” In addition, the court could consider other factors, such as age, time served, diminished physical condition, defendant’s risk for future violence, and evidence that the circumstances have changed so that continued incarceration is “no longer in the interest of justice.” The court is required to consider these additional factors: psychological, physical or childhood trauma, abuse, neglect, intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and whether the person was under the age of 26 at the time of the offense.

All felony offenses may be considered for reconsideration, and at any time. Also, the court previously could, but is now required, to consider post-conviction factors, such as age, disciplinary record, record of rehabilitation, physical condition, etc. The court must determine whether these circumstances have changed so that “continued incarceration is no longer in the interest of justice.”

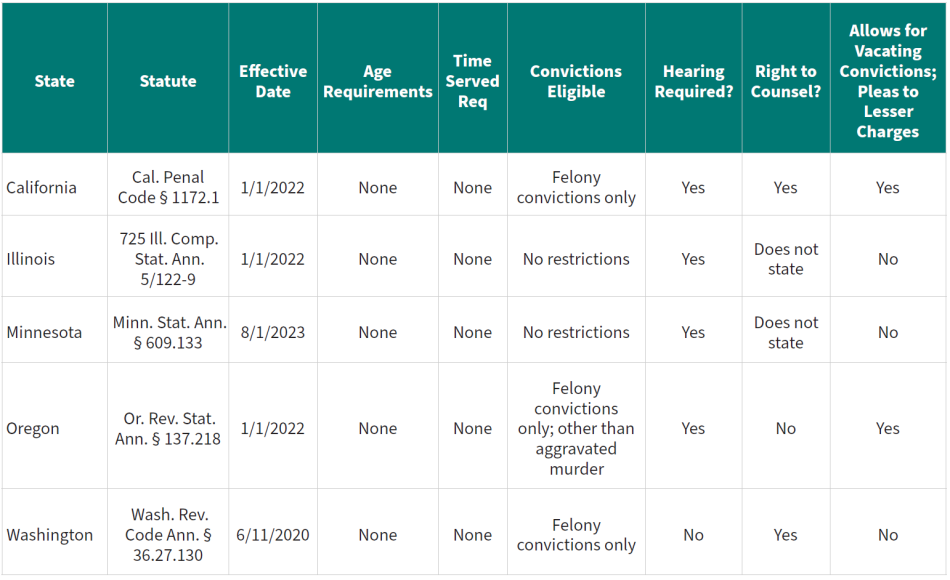

Prosecutor-Initiated Resentencing – California, Washington, Oregon, Illinois, and Minnesota

There has been a recent movement in prosecutor offices to proactively look back at sentences of people still incarcerated after they have served a significant time period in order to determine if the sentence, under today’s standards, was unduly harsh, stemmed from outdated practices and policies, or no longer serves the interest of justice. The nonprofit organization For The People, touts that prosecutor-initiated resentencing (PIR) is a “powerful tool to help repair the damage” of the disproportionate incarceration of Black and Brown people.”

In 2018, California enacted the nation’s first PIR law that allows prosecutors to petition the court for a reduction of sentence for those with felony convictions. As of 2024, four other states – Washington, Oregon, Illinois, and Minnesota – have PIR laws. In the past three years, PIR legislation has been introduced in seven other states – Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Utah, and Texas. In 2023, the American Bar Association adopted a resolution recommending that all states and the federal government adopt prosecutor-initiated resentencing legislation “that permits a court at any time to recall and resentence a person to a lesser sentence upon the recommendation of the prosecutor of the jurisdiction in which the person was sentenced.”

At the end of 2023, over 900 people have been resentenced as a result of PIR. Only two of these resentencings occurred in Illinois. Of those 900, over 400 were released from California alone and the remaining 500 from other states.

In passing PIR, the California Legislature declared that the purpose of sentencing is “public safety achieved through punishment, rehabilitation, and restorative justice.” This same intent was echoed by the Washington and Illinois state legislatures and both provided this same additional rationale: “By providing a means to reevaluate a sentence after some time has passed, the legislature intends to provide the prosecutor and the court with another tool to ensure that these purposes are achieved.”

In 2023, the Louisiana Supreme Court struck down a statute that allowed a district attorney and petitioner to jointly enter into any post-conviction plea agreement to amend a conviction or sentence with the approval of the court. The majority wrote that the law unconstitutionally allowed a judge to reverse a conviction “merely because the defendant and the district attorney jointly requested the court do so.” The law lacked guardrails requiring the finding of a legal defect. However, the majority emphasized that the opinion did not prevent resentencing from continuing under Louisiana’s remaining post-conviction statute. The Court recognized that a prosecutor must have discretion to join an application for post-conviction relief because of their “responsibility as a minister of justice . . . to achieve the ends of justice.”

State Prosecutor-Initiated Resentencing Laws

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.