The Terrorism Confinement Center was designed to be a black hole. When Nayib Bukele’s flagship “megaprison”—known as CECOT, after its Spanish acronym—opened in January 2023 in a desolate stretch of Tecoluca, about forty-five miles from San Salvador, his administration boasted that people held there “would not have contact with the outside world again.”

Bukele has made global headlines for cultivating an air of millennial cheekiness, making Bitcoin a national currency, and storming the halls of Congress with soldiers, but it’s his gulag that most defines his rule. Having reportedly spent years secretly negotiating with Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18, the two gangs at the heart of the country’s surging violence, in 2022 he responded to an especially homicidal weekend of killings by declaring a state of emergency, detaining anyone even allegedly affiliated with either group, and jailing them in ostentatiously brutal conditions. Within years El Salvador had traded the highest homicide rate in the world for the highest per capita incarceration rate in the world. In a country of six million, about one in every fifty people is imprisoned; less than a quarter have received a sentence.

Being young, poor, male, and tattooed in Bukele’s El Salvador can practically be a life sentence. “Once an inmate enters CECOT,” the prison’s director told Agence France-Presse this past January, “he never leaves.” So far he seems to have kept his word. A recent court filing by Human Rights Watch stressed that people detained in CECOT are held almost entirely incommunicado, cut off from family or lawyers, and “only appear before courts in online hearings, often in groups of several hundred detainees at the same time.” The group was, it said, “not aware of any detainees who have been released.”

Bukele’s government claims that the prison can hold 40,000 people—over six times more than Angola, the largest maximum-security prison in the US. At that capacity, as the Financial Times reported in 2023, the facility would “set records for deliberately designed overcrowding,” giving each inmate “less than half the minimum [space] required under EU law to transport midsized cattle by road.” The Salvadoran government is not disclosing how many people are currently confined in the prison, citing “security reasons,” but when a CNN correspondent visited in April, officials said that they were approaching capacity. The journalist asked what will happen once they reach it. “Well, we’ve got plans for that,” an official replied. He said those plans include a second CECOT.

For years CECOT was known in the US primarily as evidence of a young autocrat clamping down on his population. Then, in March, the Trump administration paid Bukele a reported $6 million to take 288 Venezuelan and Salvadoran migrants, the vast majority of whom have no criminal records, into custody.1 Bukele announced their arrival with what has become the prison’s visual signature: a slick, medium-production video, with dramatic music, of people being frog-marched off a plane, shackled, forced onto their knees to have their heads shaved, and pushed into a brightly lit dungeon full of four-tier bunks overcrammed with dozens of rail-thin men in white boxer shorts. The migrants would be held for a year, Bukele said—but the term is “renewable.”2

What laid the groundwork for this level of exhibitionistic state violence? To understand why the US is leaning so heavily on this tiny Central American country—and its millennial autocratic leader—as Trump tests the limits on illegal deportations, one must grasp both the profound political changes El Salvador itself has undergone since 2019 and the longer history of US–Salvadoran relations. The US has a long record of relying on other countries to deter and detain migrants, and its anti-immigrant right has long found Salvadorans particularly inconvenient.3 During the civil war that decimated the country in the 1980s, the US denied legal entry to the vast majority of people fleeing the violence even as it funded, trained, and provided material support for the military dictatorship. (The asylum grant rate for people fleeing El Salvador during the war hovered around or below two percent.) But hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans still managed to relocate to the US. Many ended up in Southern California, where some joined small gangs and picked up strategies for defense and extortion in American prisons.

After the war ended with the Chapultepec Peace Accords in 1992, the US, having just helped rip their country to pieces, expedited the process of deporting these young men back. Weakened by years of clientelism, corruption, and violence, El Salvador was hardly ready to receive them or reroute them into the formal economy. Extraordinary levels of gang violence soon gripped the country. Unlike the US, however, El Salvador doesn’t have an El Salvador to dump the people it deems disposable. So it built a CECOT. By selling space in CECOT to the US, Bukele has in effect brought this long history of violence full circle.

*

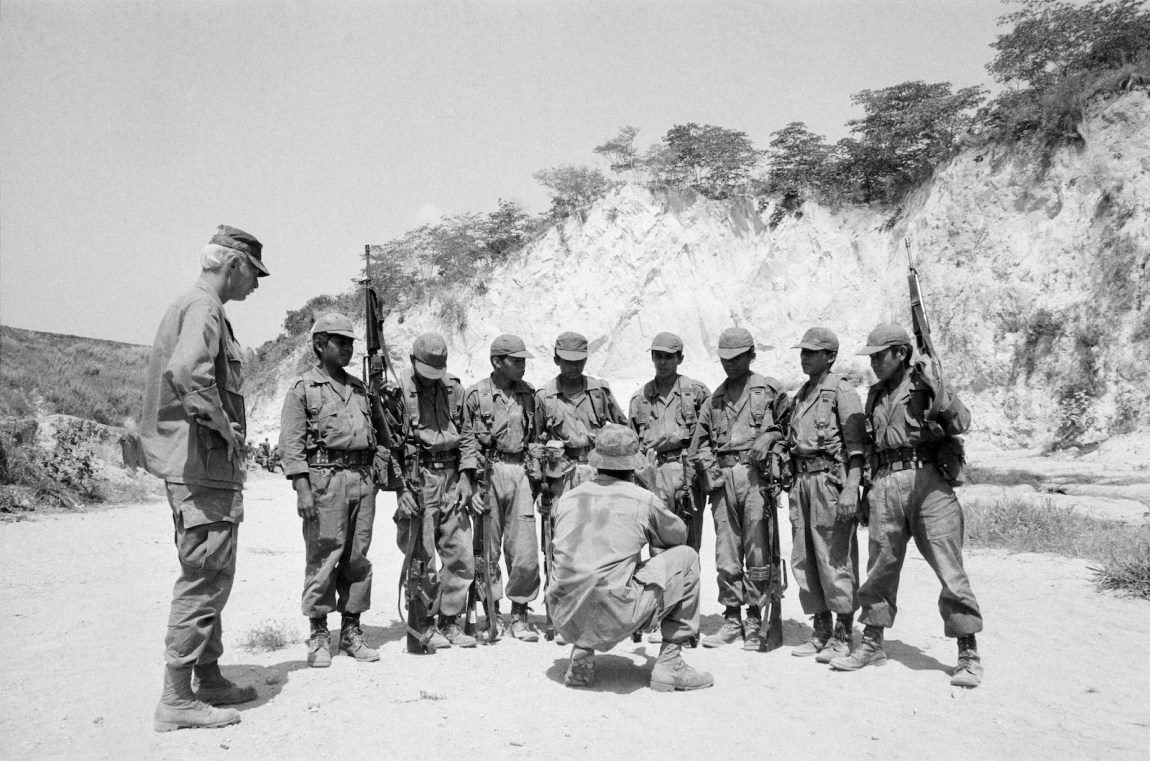

“For decades,” as Roberto Lovato wrote recently in The Nation, “El Salvador has served as a laboratory for students of war, state violence, and other repression, including those in the Pentagon, urban police forces, and the prison-industrial complexes throughout the United States.” US government advisers started training the Salvadoran security forces as early as 1957, when, as Raymond Bonner wrote in his book Weakness and Deceit (1984), officials associated with the Agency for International Development “reorganized the police academy, wrote a textbook for the Treasury Police, and trained special riot control units” under the guise of rooting out corruption. In reality, Bonner stressed, their focus was always on stamping out any hits of communism. When Murat Williams, the US ambassador to El Salvador during the Kennedy administration, arrived in the country in 1961, according to Bonner, “he was horrified to discover that the United States had more air force personnel in the country than the Salvadorans had planes and pilots.”

El Salvador was ripe for uprisings. In the 1960s and 1970s rampant inequality, corrupt governance, and military rule laid the conditions for multiple coup d’etats and counter-coups, mostly orchestrated by factions of the armed forces jockeying for power against one another or against civilian governance; in 1963 an article in the New York Herald Tribune estimated that seventy-five people in the country controlled 90 percent of its wealth. It was in this setting, that same year, that the Kennedy administration launched SOUTHCOM, the US military command center that coordinated counterinsurgency operations against the specter of communism—the threat of another Cuba—in much of the hemisphere, and that had a particular stake in El Salvador. What increasingly defined those operations, as the historian and human rights activist Michael McClintock wrote in his study The American Connection: State Terror and Popular Resistance in El Salvador (1985), was “the routine practice of terrorism—or counter-terrorism.” The US counterinsurgency doctrine “adopted uncritically throughout most of Latin America” in the ensuing decades, McClintock wrote, “rationalized, sanitized, mechanized and institutionalized what had been traditionally deplored as barbaric and shameful: torture and murder by the state.”

In the mid-1970s Salvadoran security officials attacked the villages and families of peasant union members, massacred and disappeared student protesters, bombed church buildings and political organizations’ offices, and assassinated left-wing resistance leadership. The US kept pouring on support, money, and arms. Then, in 1979, a coalition of military officers overthrew the president of the military dictatorship, Carlos Humberto Romero, in a coup that was, McClintock writes, “carried out with the full approval of the United States.” Both the US and the Salvadoran military feared that Romero wasn’t strong enough to hold onto power; they sought to replace him with a more stable regime.

Theoretically, stability would follow such reforms. That’s not what happened. “Under Romero’s rule,” as Robert Armstrong and Janet Shenk write in El Salvador: The Face of Revolution (1982), dissenting mass mobilizations “typically resulted in beatings, arrests, and later, the disappearance of those presumed to be the ringleaders. But the October coup was supposed to change all that. It didn’t.” The new regime offered civilians a place in the junta and threw workers crumbs, such as agrarian reform, but those were merely surface-level changes: not only did the new leadership fail to account for the disappeared, it kept massacring dissidents and started using agrarian reform as cover for mass murder and repression.

The tide shifted in March of 1980, when the widely popular Archbishop Oscar Romero was shot dead while giving mass in San Salvador the day after delivering a sermon denouncing the repression. Until then popular organizations largely still believed in protest and civil disobedience; soon after, they took up arms. By the end of the year what had been an aboveground mass movement had come to center on armed insurgency, and various armed groups had coalesced to form a united front called the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN).

The US was quick to pick a side. In early 1981 the outgoing Carter administration rushed $5 million dollars of lethal military aid to the Salvadoran regime on the pretext that the US had discovered a few Nicaraguan boats carrying Soviet arms via Cuba for the guerillas—what the US called a “textbook case of indirect armed aggression by Communist powers.” El Salvador was coming to seem like a chance to rehabilitate the US war machine after the extended disaster of the war in Vietnam—to prove that US forces could train and fund an anticommunist fight without the disastrous entanglements and mass death that took place in Southeast Asia. Just a month after Carter’s military largesse, Secretary of State Alexander Haig, in reference to perceived communist creep, said that he would “draw a line in El Salvador.”

The State Department called it “clean counterinsurgency,” Armstrong and Shenk write: the US presumed it was easy “to distinguish between a mere peasant and a militant, and shoot only the latter.” But to “the Salvadoran army, any peasant was suspect, even children were subversive.” And by that point the army had learned that “Washington would back them no matter what.” The same year Haig drew his line, El Salvador’s Atlacatl Battalion, generously funded and trained by the US Army, murdered more than eight hundred people in the small town of El Mozote. As the US journalist Felipe de La Hoz has related in the independent investigative Salvadoran media outlet El Faro (where I once worked as an English-language editor), 245 shell casings were recovered at a convent where “about 140 children were slaughtered and set on fire.” Of those, “184 bore recognizable markings identifying the bullets as having been manufactured for the US government in Lake City, Missouri.”

Incidents such as the El Mozote massacre were anomalous only in their magnitude: bodies frequently turned up in those years, often bearing signs of torture. A weekly memo dispatched from the US embassy back to Washington in 1982 noted, as Joan Didion pointed out in these pages, “that it is generally believed in El Salvador that a large number of the unexplained killings are carried out by the security forces.” And yet it insisted that the country’s “tangled web of attack and vengeance, traditional criminal violence and political mayhem” made such claims impossible to verify—despite much evidence to the contrary. And so US military aid continued, eventually amounting to billions of dollars in total. At one point as much as $1 million arrived per day.

*

In The Hollywood Kid: The Violent Life and Violent Death of an MS-13 Hitman (2019), which I cotranslated with Daniela Maria Ugaz, the journalist Óscar Martínez and his brother, the anthropologist Juan José Martínez, write that by supporting the Salvadoran military the US was “flicking a cigarette into a field of dry grass.” The result, despite US efforts to deny migrants entry, was the mass northward exodus of the 1980s. Many Salvadorans settled in Los Angeles, “hundreds of them every day, carrying the dust of a civil war on their thin-soled shoes.”

Of those new arrivals, many “were young kids who’d already known war,” having been forcibly conscripted by the military and sent “to kill and die in the mountains.” The guerillas, too, the Martinezes write, were “in the business of training kids and teenagers.” When youth shaped by this brutal landscape found themselves confronted by Los Angeles’s complex network of organized crime, in the brothers’ account, they tried to take on the established gang members at their own game.

Partially in response to the uprisings after the Rodney King verdict in 1992, which also destabilized parts of Southern California’s gang ecosystem, in 1994 Bill Clinton pushed for a crime bill that imposed harsher sentences, significantly increased the size of police forces, and had the effect of funneling a number of these Salvadoran gang members into new and bigger prisons—many of which were, as it happened, partially controlled by prison gangs. At the same time, Clinton was cracking down on immigration. Two years later he signed another bill, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which made it more difficult to seek and be granted asylum, allowed for migrants to be sent back to their home countries much more quickly and without a trial, and created more categories to subject immigrants to criminal charges—all of which made it easier to expel Salvadoran migrants back to “the birth country that they hardly knew.”

“Academics who claim that gang structures arrived in Central America with the deportees are correct,” the Martínez brothers write, “but within that truth lies a whole spectrum of subtlety.” For decades the gangs grew, took control over swathes of territory, and held residents hostage. And yet they were also part of local communities, weaving themselves into the social fabric and assuming de facto political governance over many jurisdictions. Successive administrations, including those of Francisco Flores and Antonio Saca, implemented zero tolerance policies—from mano dura (iron fist) to súper mano dura—to crack down on the gangs even as they continued to negotiate with their members behind closed doors.

*

These decades of discontent and insecurity were Bukele’s to harness. The son of a well-off businessman of Palestinian Christian descent who converted to Islam, Bukele spent his twenties in marketing and political advertising. He got his start in politics in 2012, when at thirty-one he narrowly won the mayoral race in the tiny city of Nuevo Cuscatlán. He ran on the ticket of the FMLN, which had transformed after the war into a political party.

The country’s capital, San Salvador, was less than ten miles away. Three years later, having acquired a reputation for progressive politics and a focus on youth, Bukele won the city’s mayoral elections. In the process he reportedly benefitted from his party’s connections with the gangs he would later denounce. In a major interview with El Faro last month, two former Barrio 18 leaders with inside knowledge of the negotiations alleged that the FMLN, in the outlet’s summary, “paid a quarter of a million dollars to the gangs during the 2014 campaign in exchange for vote coercion in gang-controlled communities,” including “on behalf of Bukele for San Salvador mayor.”

Bukele’s relationship with the FMLN had long been one of convenience: initially he embraced leftist policies but largely dismissed their revolutionary rhetoric. In 2017 the party expelled him after he got into a standoff with another member and allegedly threw an apple at her head. But by that point he was already building his own brand, which would become the party Nuevas Ideas. When he ran for president in 2019, at just thirty-seven, he won in a landslide.

Since taking office Bukele has pursued a range of means of consolidating power. He has long targeted dissenting critics and journalists, dozens of whom had their phones hacked using Israeli-developed Pegasus spyware between 2020 and 2021. In 2020 he ordered the military to break into the halls of the legislature and take over the main chamber of Congress in a hypermilitarized show of force. “It’s very clear now who’s in control of this situation,” he said. Then he bowed his head in prayer; later he insisted that God had been speaking to him. He gave the legislature a week to approve a $109 million loan for the third phase of his “Territorial Control Plan,” which focuses on eradicating the gangs and includes major spending on the country’s police forces, threatening another military takeover if they didn’t.

A year later he used his party’s supermajority to ignore the constitution and purge the judiciary, sack the attorney general, and replace his critics with favorable judges; Bukele-installed magistrates ruled later that year, in direct violation of the constitution, that he could run for another term. At the time the US secretary of state warned Bukele about his administration’s lack of judicial oversight and its threats to “democratic governance.”

The Territorial Control Plan itself has by now gone through six “phases.” The early ones, including “Opportunity” and “Modernization,” sounded like steps in a business expansion model. Then they turned more martial: “Incursion,” “Extraction.” These phases saw massive shows of force and sweeping arrests, often of young men with merely presumed gang affiliation. For years this strategy reportedly ran in secret parallel with one of directly negotiating with the gangs. In a 2022 indictment filed against more than a dozen gang members and MS-13 leaders, including one with the nom de guerre Vampiro de Montserrat Criminales, the US attorney for New York’s Eastern District alleged that Bukele’s administration traded reduced prison time, improved conditions, and non-extradition in return for fewer—or less visible—murders in the country. (Bukele has always denied making any such deal.) According to the interviews recently conducted by El Faro, one top Bukele negotiator reportedly encouraged gang members to disappear their victims: “No body, no crime.”

The pact supposedly broke down in March 2022, when the gangs unleashed a wave of violence on the country—at least eighty-seven people were killed in one weekend—and Bukele responded with his own show of force, declaring a state of emergency and ordering the military into the streets. The state of emergency, which practically eliminated due process, was set to last for a month, the maximum length allowed by the country’s constitution. But it’s renewable by the legislature, where Bukele’s party has fifty-four of sixty seats. So far Bukele-aligned lawmakers have extended it nearly forty times.

In December 2022, before CECOT opened, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal issued a joint report alleging that the crackdown had “aggravated historically poor conditions in detention, including extreme overcrowding, violence, and poor access to goods and services essential to rights, such as food, drinking water, and health care…and, in some cases, torture and other forms of ill-treatment.” Children were not spared: in a follow-up report HRW found that “over 3,300 children have been detained, many without any ties to gang activity or criminal organizations.” More than sixty of them had been “subjected to torture, ill-treatment and appalling conditions.” Deaths as a direct result of medical neglect and physical abuse by prison authorities—including beatings and electric shocks—have been recorded in high numbers.

The fear incited by CECOT has provided new opportunities for exploitation. El Faro recently uncovered that prison officials have reportedly been charging extortionary fees to allow family members to visit or communicate with people detained in the facility. People who have spoken out about abusive conditions have been locked up. Human rights groups have been denied access to CECOT and other prisons; so have journalists. “Since the opening, media access has been carefully selected and staged at CECOT,” El Faro reports. While Bukele has let in a few big US outlets and state-friendly YouTubers, he has barred the Salvadoran independent press. Last month at least three journalists with El Faro decided to leave the country after they were alerted that they might be arrested, joining four who had already left. That tip-off came amid a wave of repression, including the arrest of the prominent human rights lawyer Ruth López, head of Cristosal’s Anti-Corruption and Justice Unit.

Many Salvadorans have so far been willing to countenance the loss of these freedoms as the price of their newly enjoyed security and the end of the gangs’ reign. Bukele’s approval ratings have climbed to over 90 percent, if the polling is to be believed. One woman who spoke with CNN praised his tactics for returning safety to the streets even as she lamented the fact that her own son was, she claims, wrongly detained during the state of emergency. These are what El Faro’s Roman Gressier has called Bukele’s “twin swords of popularity and fear.”

*

Popularity and fear are also tools wielded by Bukele’s counterpart in the US, with whom he has some striking commonalities. Both presidents have waded into cryptocurrency trading, though Bukele got a head start, announcing three years ago to the cheers of the tech bros that El Salvador would be the first country to use Bitcoin as a national currency. (Like many crypto endeavors, the experiment has had mixed and mostly bad results. As of May 1 Bitcoin is no longer official currency in the country; people can still use it, but not to pay taxes or state bills.) Both men have delusions of monarchial grandeur: recently Bukele changed his bio on X to “Philosopher King”; Trump, before the new pope was named, posted an AI-generated image of himself in full papal pomp. They both flirt with the idea of a third term, and both have courted constitutional crises. As Bukele sat in the White House during a press conference and insisted that he wouldn’t return a wrongly deported man, Trump smirked with what looked like paternal pride.

Both, too, have learned that if you no longer have real conditions of crisis to exploit, you can always manufacture them. Trump has long taken advantage of the high number of crossings at the US southern border to stoke fear and attempt power grabs. Those crossings, even at their height, were neither violent nor a threat—in fact they were often a response to threats of violence. They have also, for that matter, plummeted in recent months. Gang violence in El Salvador, unlike migration at the southern border, was indisputably a real crisis, but it, too, has fallen sharply. That hasn’t stopped either Trump or Bukele from treating them both as ongoing threats for the sake of invoking or renewing states of emergency. Militarized policing machines inflict real material violence, but for Trump and Bukele they are, at root, a matter of spectacle. (In Trumpian terms you might call it showmanship.) Organizing an extreme response to the mere presence of noncitizens walking down the street incites the very fear it purportedly protects against.

One of the primary features of that spectacle is forced disappearance—a form of violence that depends at once on making arrests and detentions hypervisible and on consigning the victims to invisibility. During the civil war approximately nine thousand people went missing, many of them disappeared by the dictatorship. Since Bukele assumed the presidency, a Salvadoran organization called the Foundation of Law Enforcement Studies has tallied almost 6,500 reports of disappeared persons.

Trump is turning to the same tactic. In a recent piece for El Faro, the Venezuelan human rights researcher Carolina Jiménez Sandoval reflected on the historical echoes of seeing migrants shipped off to CECOT from the US. “The constant pain of not knowing a loved one’s whereabouts, amid an endless search for any clue that might lead to finding them, is a feeling many in Latin America know too well,” she writes. Today too, she noted, the migrants deported to El Salvador under the Trump administration had “their names removed from official databases,” and neither government revealed “their identities and whereabouts…to their relatives or legal representatives.” Of the 288 people rendered to El Salvador from the United States, researchers and journalists have identified only 258.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.