Prisons across the United States run on incarcerated labor. People behind bars cook food, sew clothes, clean facilities, manufacture goods, and even work in dangerous industries like agriculture and firefighting—often for just cents an hour or, in some states, nothing at all.

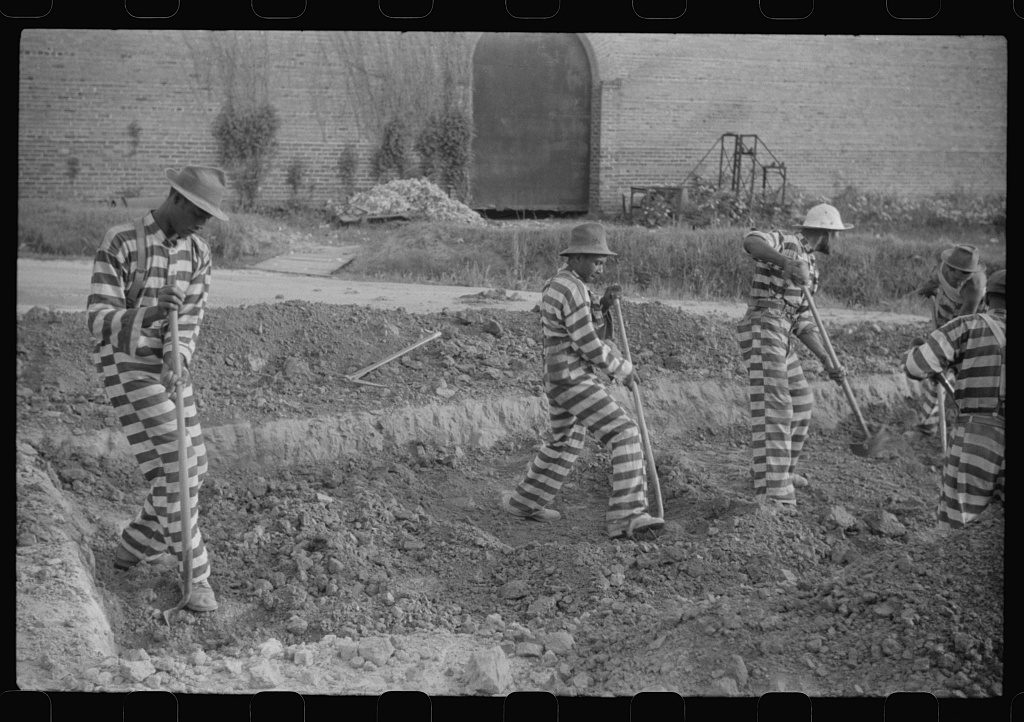

This reliance on coerced labor has deep historical roots. After the Civil War, states—especially in the South—built a network of laws to criminalize formerly enslaved people and created a system of prison labor that sent almost entirely Black men and women into coal mines, plantations, and railroads under the banner of “convict leasing.” Some state constitutions still contain explicit exceptions that allow forced labor for incarcerated people, a direct legacy of the 13th Amendment’s “exception clause.”

We suspected you had questions about this system of forced labor, so we asked you to reach out and let us know as part of our series “Ask Bolts.”

And we invited Robert Chase, a historian at Stony Brook University and the author of We Are Not Slaves: State Violence, Coerced Labor, and Prisoners’ Rights in Postwar America, to answer you. Chase’s research traces how southern prisons built a lucrative system rooted in exploitation, how reforms often intensified labor divisions, and how incarcerated people organized resistance movements to fight back.

Chase answers ten questions, below. Navigate to the question that most interests you here, or scroll down to explore them all at your leisure:

How did convict leasing evolve?

What is the legal basis for this system today?

Where does prison labor occur?

Which industries rely most heavily on it?

What happens when prisoners refuse to work?

Can prison labor be exploitative if some want to work?

What organizing efforts have been the most effective?

How do you include incarcerated voices in your research?

How could you stop prison labor, and would closing constitutional loopholes be enough?

Read on to learn more, from the roots of prison labor in the 19th century to the resistance movements pushing for change today.

How did the system of convict leasing evolve after the Civil War, and what industries were most reliant on it? — JD

Convict leasing, the system by which prisoners were leased to corporations as “slaves of the state,” officially began in Alabama in 1846. What drove the Southern turn towards convict leasing was a series of laws that criminalized what had previously been petty crimes. Newly passed “vagrancy laws,” in particular, criminalized Black people who were out of work. Failure to pay a tax, for instance, also counted as vagrancy, as did simply gathering in public space or being in a public space without a work pass designating where one worked. Nine Southern states updated their vagrancy laws in 1865-1866, which included tying newly free African American people to the land with labor contracts that criminalized them if they tried to leave.

In the wake of these laws, the number of coerced and incarcerated laborers ballooned. In Georgia, incarcerated populations increased tenfold during the four decades (1868–1908) when the state turned to convict leasing. In Alabama, it went from 374 in 1869 to 1,878 in 1903, and then increased to 2,453 by 1919.

Although convict leasing was different from slavery—no one was born into this condition and it was not inherited—more than 90 percent of prisoners in the convict lease system were Black men and women. In some cases, former plantation and slave owners, like J.W. Comer, turned their fortunes around by pivoting from slavery to convict leasing. Comer, a former plantation master in Alabama, later owned the Eureka Mines where he leased hundreds of prisoners to do dangerous mine work. In other cases, prisoners were leased to companies that used convict labor to modernize and industrialize the South.

The conditions were horrible: Prisoners were whipped and routinely victimized by sadistic guards; Black women were subjected to coerced sexual violence and forced pregnancies; and convict laborers were frequently held in cages in rural camps where they were ill fed and ill clothed. Mortality rates among leased convicts were startlingly high from working in hazardous industrial and coal mining industries approximately 10 times higher than the death rates of prisoners in non-lease states. In 1873, for example, 25 percent of all Black leased convicts died.

Convict leasing was a critical engine for corporate capitalism and the modernization of the South. The prisoners’ “contracts” could be bought and sold by private interests, such as plantation owners and corporations, including coal-mining firms, railroad construction companies, lumber bills, the turpentine industry, and national companies such as U.S. Steel. In this exchange of cheap, unpaid labor, the state saved on the cost of housing and feeding the prisoners while also receiving an income for leasing their labor. It was immensely profitable. In the mining state of Alabama, about 10 percent of its total revenue was derived from convict leasing in 1883. By 1898, that number had jumped to 73 percent—and the state made nearly $100,000 that year on convict leasing. Georgia, Mississippi, Arkansas, North Carolina and Kentucky made less, but these states still profited between $25,000 and $50,000 each year.

These are astronomical figures, starkly revealing how convict leasing effectively returned the South to a space of coerced and unfree Black labor that served as a critical engine for corporate capitalism—bridging the agricultural slave economy and modern industrial development—while upholding white supremacy and racial subordination in the new Jim Crow South.

What’s the legal basis that allows prisons to pay way below minimum wage or not pay at all? Do minimum wage laws not apply at all? — Jae, from California

Nationally, a total laboring prison population of nearly 900,000 people is coerced to work for a $2 billion-a-year prison industry. Minimum wage laws do not apply to those convicted of a crime. The average daily wage is 86 cents, which represents a decline from 91 cents in 2001; the average maximum daily wage for the same prison jobs has also declined during that time, from $4.73 in 2001 to $3.45 today. Yet up to 80 percent of these meager wages can be withheld for reasons such as “room and board.” In 2022, seven states, all in the South, paid no wages at all for regular (non-industrial) jobs: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina and Texas.

Simply put, the legal basis of prison labor with nominal or no pay is the 13th Amendment, which outlawed the private ownership of slaves, but allowed the state to put prisoners to work through the “exception clause” that states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.” Following the 13th Amendment, most state governments then also placed an exception clause in their state constitutions, particularly in the U.S. South. Some state Supreme Courts even declared prisoners as “slaves of the state,” as Virginia did with the 1871 Ruffin v. Commonwealth decision.

Only recently has that been challenged through state referendums to strike down the “exception clause.” Since 2018, eight states have struck down “slavery” and involuntary and coerced prison labor, including: Colorado in 2018, Utah and Nebraska in 2020, and Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee and Vermont in 2022, and Nevada in 2024, although it’s largely symbolic in that state because Nevada left it up to the courts. Other states, such as Louisiana (2022) and California (2024), however, rejected the effort to remove the exception clause.

Where does prison labor occur? Is it in both state and federal prisons? — DB, from California | Do private prisons differ from state-run prisons in their use of prison labor? — @diamondveto, on BlueSky

For much of the twentieth century following the end of the convict leasing system, legislation prohibited prison labor for private profit. Starting in 1929, a series of national and statewide laws ushered in the era of state-made use, meaning prison labor could only be done for the state: Prisoners made license plates, built furniture for state use (such as desks for universities), built and cleaned roads, and engaged in massive agricultural labor in Southern prisons.

But that all changed in 1979, when Congress passed the Prison Industries Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP), which chipped away at the New Deal-era block on selling items made from prison labor across state lines by allowing third-party vendors to establish local businesses in states and then sell prison-made goods across state lines to national corporations.

Today, 58 percent of able-bodied incarcerated people in state prisons have a job assignment. What kind of work they do varies by state, but typically includes work in food service, janitorial work, laundry, agricultural work, industrial work, and service jobs for the prison.

In federal prisons, 100 percent of able-bodied federal prisoners are required to work. The number of people who work in UNICOR, the trade name for federal prison industries, is 22,560. These incarcerated laborers earn between 23 cents and $1.15 per hour. Meanwhile, UNICOR’s 2001 sales stood at $583.5 million.

Unlike state and federal prisons, private prisons, which operate in 27 states, are not required to release information about the kinds and amount of prison labor that incarcerated people perform in a private prison. They do work, however, and the products that they produce are similar to the prison industries that operate in state-run prisons.

What companies or industries have relied most heavily on prison labor? — Peter B., from Maine

Since the passage of PIECP, a host of multinational corporations have used this labor, including Whole Foods, McDonald’s, Target, IBM, Victoria’s Secret, and many others. In a two-year study of prison labor and the supply chain of major food producers, the Associated Press reported that agricultural goods made by prison labor are in the supply chains of a number of household foods and on the shelves of supermarkets, including Frosted Flakes cereal, Gold Medal Flour and Coca-Cola. Indeed, the soy, corn, and wheat harvested by agricultural prison laborers has made its way to the global marketplace through international commodity traders such as Cargill, Bunge, Louis Dreyfus, Archer Daniels Midland and Consolidated Grain and Barge.

Public and private universities also benefit from low-paid to unpaid prison labor. In 2019, I filed a state-level freedom of information request on prison sales to universities in New York, where I am a professor at Stony Brook University, and in Texas, the subject of my book We Are Not Slaves: State Violence, Coerced Labor, and Prisoners Rights.

I found that Stony Brook University and its hospital spent nearly $40,000 in 2019 prison-made goods. When tallied together, the entire SUNY system spends $484,295 on prison-made goods. Yet incarcerated workers earn only a paltry average of 62 cents an hour (about $1,092 per year) to make products for New York state’s thriving $50-million-a-year prison labor industry.

In 2019, Texas’s public universities bought $383,874 in merchandise from Texas Correctional Industries (TCI), a for-profit corporation operated by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. While nearly all Texas prisoners who work aren’t paid whatsoever, TCI posted nearly $89 million in profits during 2014.

If someone is incarcerated and refuses to work, what are some of the ways that prisons have been known to respond? — Christopher W., from New Jersey

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, 71 percent of people with prison jobs are required to work and 29 percent chose to work. Refusing to work is often not possible, as to do so can often result in punishment, like losing “good time” (time off their sentences for days worked) and educational opportunities, or a worse cell assignment and even the threat of solitary confinement. According to a recent report by the University of Chicago Law School’s Global Human Rights Clinic and the American Civil Liberties Union, 76 percent of incarcerated workers reported that they faced discipline if they refused their job assignment.

To give you an example from my book: On Sunday June 17, 1973, prisoners at Texas’ Retrieve prison were ordered to harvest a crop of nearly rotten sweet corn. This angered prisoners as it would mean working on Sunday, the only day when Texas prisoners did not work, and it was also Father’s Day, a day when many incarcerated fathers expected a visit from their families. A number of prisoners who stayed in their cells and refused to work were beaten by guards with batons, baseball bats, and rubber hoses. Bloodied and only half dressed, some without shoes and others just in their undershorts, these prisoners were then taken to the cornfields and forced to pick wet corn with long heavy bags that became unwieldy as they filled with corn and slick mud. Guards on horses rode over the workers and beat them again while all the other prisoners were collected from their field assignments to watch them. As one beaten prisoner recalled, they were “the example for all to see.”

Does anything like ADA and its job accommodations exist within prison walls? Or are disabled people essentially barred from holding a prison job in certain circumstances? — Ellery

Yes, in 1998, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Americans with Disabilities Act does apply to incarcerated workers. In DOC v. Yeskey, a man incarcerated in Philadelphia sued the state after his placement in a motivational boot camp that would have seen him earn parole in six months was rescinded on account of his medical issues. In the majority opinion, Justice Antonin Scalia affirmed that “the text of the ADA provides no basis for distinguishing these programs, services, and activities from those provided by public entities that are not prisons.”

Recently, this protection has extended to incarcerated people with mental illness. In 2013, the Department of Justice conducted an investigation into Pennsylvania’s practice of placing mentally ill prisoners in solitary confinement, who were found to experience extreme distress, including mental decompensation, clinical depression, psychosis, and suicide. As such, the DOJ found that solitary confinement for incarcerated people with mental illness was tantamount to a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment.” However, the Justice Department’s finding has not changed the fact that many prisoners with mental health problems are still forced into the 23-7 arrangement of cell isolation (23 hours a day, seven days a week) in Supermax prisons and in wings of total administrative segregation.

How do/can we square the fact that some incarcerated people want to work, and apply for jobs in prison and occasionally like them, with the fact that prison labor, even when not forced, is inherently exploitative? I’m also wondering what Robert Chase has heard from incarcerated people themselves on this conundrum. — Aristophanes

Prison labor is always exploitative because it is always about extracting profit, whether for the state or private businesses. But it’s true that many incarcerated people want to work to get out of the drudgery of their cells, to earn even a little money for their families, to see their labor go to recompense programs for victims of crime, and to have a sense of productivity as part of their sentence.

But what incarcerated people do not want is to be exploited, to be worked as unpaid slaves, to receive pennies an hour for their labor, to work in hazardous conditions, or to be forced to work if they do not wish to do so.

I’ve been in contact with some of the founders of the Free Alabama Movement, The End Prison Slavery Movements in various states, and the International Workers of the World Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, and in all those conversations these activists and politically conscious incarcerated people feel that prisons constitute modern-day slavery. They organize other prisoners around that basis, fighting for fair compensation, safe working conditions, and laboring without compulsion under threat of penalty.

In recent decades, where has organizing by prisoners been most fruitful, and what strategies have worked? I’m thinking partly of protest activity at Red Onion State Prison over the last year. — Robert, from Rhode Island

Resistance from incarcerated people has created a nationwide abolitionist movement against mass incarceration that has sought to strike down the “exception” clause in state constitutions that had previously allowed slavery and involuntary servitude for those convicted of a crime. A recent wave of statewide prison work strikes and actions began in 2010, and the first ever nationwide strike took place in 2016, when 24,000 prisoners in over 29 prisons across 23 states refused to work. The strike’s manifesto, “Call to Action Against Slavery in America,” declared, “We will not only demand the end to prison slavery, we will end it ourselves by ceasing to be slaves.”

Much of the organizing for this strike came out of the South, particularly from the Free Alabama Movement, the Free Mississippi Movement, and the End Prison Slavery in Texas movement. But facing the threat of administrative lockdowns and individual punishments, the strike ended within a month with its demands unmet. The strikers’ demands varied from state to state and included unionization, fair wages, better medical treatment, and more. But the shared goal among all was to draw attention to the continued use of slave labor in U.S. prisons.

Alongside such strikes have come a series of lawsuits that have gotten national attention. In one recent lawsuit in Alabama, incarcerated workers are suing the state with a claim that a work-release program allowing incarcerated people to work for retail and companies is, in fact, an illegal return to convict leasing—a sweeping and remarkable claim for its direct engagement with the history of Southern prison labor. The 1,374 incarcerated workers assigned to the program are charged for rides to work, equipment, and uniforms, and have 40 percent of their pay docked in what the lawsuit terms a “labor-trafficking fee.” Arguing this is exploitative, the suit claims that Alabama has violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, a federal law on trafficking, and a 2022 change to the Alabama state constitution that prohibits “slavery and involuntary servitude.”

These are all remarkable grass-roots campaigns to challenge mass incarceration in the courts through civil rights suits and in the prison courtyard through prison organizing and labor strikes..

How do you incorporate the perspectives of incarcerated people into your research and navigate the challenges of working with sources that are often ignored or undervalued in academic spaces? — Bolts Staff

We Are Not Slaves, published in 2020, was the culmination of nearly twenty years of research on prison systems in the American South, particularly in Texas. To take readers behind prison walls and reveal the rapacity of prison economies, my book relied on prisoner testimonies, letters, affidavits, depositions, and sixty oral histories from people incarcerated in Texas’ prison system, who contributed to resistance behind its walls.

It took years to make contact with the incarcerated activists and to establish a rapport through letter-writing that eventually resulted in my oral histories. In the course of these interviews, some of which were hours long, prisoners related the most intimate and traumatic details of sexual assaults and beatings. These were not easy stories for them to recount, but they felt it necessary to renounce the violence done to them by naming the system that allowed it to happen and exposing the worst horrors of the prison to public view. The oral histories of prisoners create an alternative testimonial against the prison’s sole stake on what constitutes “truth,” where the carceral power charts a selective narrative that all too often dismisses and silences prisoner complaints.

Who has the authority to stop prison labor? What’s the level of government that citizens should be focusing on to convince them to do so? — DB, from California | What do you think would be the practical impact(s) of “ending the exception” (the 13th Amendment exception that allows slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime), if successful? — Will

As a historian, I draw upon successful historical campaigns to challenge mass incarceration and the worst abuses of the prison system. But I also want to echo what the historian Robin D.G. Kelley has made clear, which is that we cannot evaluate social movements solely on a narrow metric of “success” or “failure” to realize their visions, but rather “on the merits or power of the visions themselves…as it is precisely these alternative visions and dreams that inspire new generations to struggle for change.” This is never more true than in the current struggle over mass incarceration, which connects distinct campaigns across time through history’s memory of how to confront the carceral state. The hope for the future is to draw on the past to remember how collective resistance requires alliances both within prison and throughout society.

One suggestion that my book offers is that social justice movements against mass incarceration should continue to focus as much attention on changes in local and state government as the civil rights movement once did when it sought civil rights as a matter of national and federal intervention. To dismantle this encompassing thicket, we must utilize the spade of history to reveal just how deep we must cut to reach the roots of intertwining carceral states.

Since 2018, eight states have struck down “slavery” and involuntary servitude in their state constitutions. This is a remarkable political feat, especially in deep red states like Alabama, but one caution that I can cite from the history of civil rights campaigns in prison is that just because a law has changed, that doesn’t necessarily change coercive systems of forced labor and prisoner abuse. Striking down prison labor as outright “slavery” from a state constitution is certainly an important political victory, but in order for it to have the most impact on the lives of incarcerated people we have to address the fact that prison labor is always an exploitative tool of labor extraction. As the recent Alabama civil rights case on convict leasing demonstrates, modern-day systems of enslavement and convict leasing continue unabated, despite the fact that Alabama struck down its exception clause. (Editor’s note: Bolts reported in 2023 that forced prison labor continues in Colorado despite a referendum that struck down the clause there.)

The struggle for true prison reform and indeed abolition is ongoing. It will take collective organizing within the prison and by their allies outside of prison to effect change through civil rights cases, lawsuits, political organizing, and unceasing political demands at the state and federal level.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.