The banging and groans from the cell above had been going on for days. Kory McClary didn’t know the name of the man, but his distress was unmistakable. McClary heard him banging on his toilet and his bunk continuously with only small breaks in between. He heard him battling guards who entered the cell. He heard him screaming in pain.

Then one morning, the sounds stopped. The prisoner had been moved to another cell. Two days later, McClary learned from a prison porter, the man was dead.

He died at New Jersey State Prison in Trenton nine days before Christmas one year ago, surrounded by surveillance cameras, other incarcerated men, and prison guards with access to his every movement.

McClary is a writer for the Prison Journalism Project (PJP), a non-profit news organization that provides incarcerated writers with tools and training. From a cell directly below the man’s cell, McClary overheard his decline over several weeks and described it in a harrowing article that was shared with MindSite News, a non-profit news outlet that covers mental health. His report led to this investigation which is being co-published, along with McClary’s report, by MindSite News, PJP and the Guardian US.

A review of public records, interviews with prison mental health experts, family members and friends, along with the man’s own writings and McClary’s observations, raise questions about his treatment and care in his final days.

The man was confined, alone, in what other prisoners call “the crazy unit”. A video camera is supposed to provide constant monitoring for suicidal actions, yet he spent his final four hours sprawled forward, motionless, on his cell toilet. That’s where guards found him, according to a review of the video footage by Lauren P Thoma, the deputy medical examiner for Middlesex county, New Jersey, who conducted his autopsy. Thoma concluded that the man had died of a heart attack.

The man’s name was Edward Robinson. He had served more than two decades of a life sentence and survived a bout of Covid-19 a year earlier. He missed the funerals of his grandmother and mother, but was still in close contact with family and friends along the East Coast, who believed they would someday be reunited outside of prison walls. He was 49 years old when he died.

This is his story.

The life and times of Edward Robinson

Edward Robinson was born in Paterson, New Jersey, on 10 June 1973. He came from a small family and was the first of three boys born to Belinda Tate, an only child whose parents were both orphans, according to his cousin, Darlene Morris.

Belinda was in the eighth grade, when “she hooked up with my cousin”, Morris said. The boy was called Little Eddie, after his father.

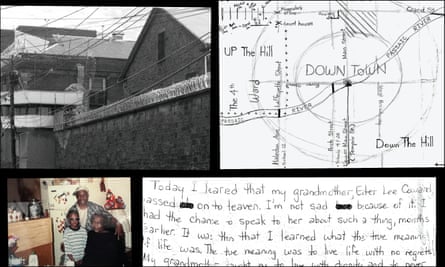

Home was the Alexander Hamilton Public Housing Project, better known as the Alabama projects because of nearby Alabama Avenue – a housing complex that became notorious for dilapidation, crime and drug dealing until it was torn down in 2010.

Belinda kept up with family tradition and made sure her boys were well dressed. But as they got older, she contracted HIV. Her mental health deteriorated and she eventually became homeless, Morris said.

“Eddie took the responsibility of his little brothers, trying to keep them up to what they were used to,” Morris recalls. But then, she said, “he got mixed up in the thug life”.

At the Alabama projects, that life was hard to escape. Its location near Route 80 made it ideal for selling drugs to users traveling from the suburbs. It was nicknamed the “dog pound” because of how easy it was to score heroin – aka dog food.

Robinson was 21 when he met the woman who would become the love of his life. Shawana Gatlin’s first impression of him wasn’t very positive, though. Little Eddie was wearing a skull hat pulled down over one eye, a big army jacket and baggy jeans with one pant leg rolled up.

She brushed him off by giving him a fake number, but he got the real one from her cousin. They talked on the phone for about six hours that night.

“I could tell how intelligent he was just in that conversation,” she said. “Even though he was from the hood, he was very articulate. He knew how to use his words. There’s a lot of guys who will try to use big words and use them out of context and they end up sounding foolish, but he just knew what he was talking about.”

The two bonded over their love of writing. Robinson had never met a girl, like her, who traveled with a folder full of poems and was on her way to Morgan State University in Baltimore. Because of his intelligence, she told him he should apply.

“Later on I found out why he couldn’t do that,” she said.

He was on the run, having escaped from a halfway house after serving a sentence for a drug charge.

Final days in 2EE

By late 2022, Robinson was one of roughly 750 people living in solitary confinement – or what is euphemistically called a restorative housing unit – in a group of four New Jersey state prisons on any given day, according to a report by the office of the corrections ombudsperson released in October that covered four of the state’s prisons.

McClary, the incarcerated journalist, says the incessant banging from the cell above him started in November 2022. The noise went on for over a week, stopped for a while and then started up again one night, leading to sounds of fighting and a man screaming like he was being murdered, McClary says. Finally, on 16 December, McClary heard a code 53 – for medical emergency – called for cell 2EE.

According to the autopsy report, Robinson had a half-inch bruise on his forehead, an “irregular abrasion” on the back of his head, and cuts on his knees and right ankle. He also had six fractured ribs “consistent with artifacts of resuscitation”. Rib fractures occur in about 30% of CPR attempts, studies show.

An autopsy’s ‘stunning findings’

The cell in the prison’s “crazy unit” where Robinson died has a dedicated camera filming the cell around the clock. MindSite News filed public records requests for video of those final hours, along with investigative records related to his death, incident reports involving Robinson and policies surrounding the use of solitary confinement. All the requests were denied by the New Jersey department of corrections, which also has not provided replies to numerous requests seeking responses to this report.

One record was provided to MindSite News: Robinson’s autopsy report. The coroner, Thoma, had access to the video and used it to recount his final hours.

On 16 December 2022, Robinson is seen on video walking around his cell, the report says. Around 3.42pm, he sits on the cell toilet backward, straddling it. Around 4.15pm, he moves his head and arms slightly and his head slumps over.

He never moves again, staying in that position until 8.28pm when the camera is moved “presumably to gain access to the cell for resuscitative efforts”, according to the autopsy.

One hour later, at 9.30pm, the 49-year-old was pronounced dead of a heart attack.

MindSite News asked Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist with decades of experience researching mental health conditions in prisons and jails and serving as an expert witness, to review the autopsy report. It has “some stunning findings”, Kupers said in an email.

Prisons usually require that officers check on inmates who are under suicide observation, Kupers said. Those checks are typically every 15 to 30 minutes.

“The video shows he was sitting on the toilet for over four hours, and incredibly he was on video the entire time, evidently, before staff even noticed that he was immobile and slumped. So what was the purpose for having him on video?” Kupers wrote.

In-cell video is typically used only “for individuals who are at high risk of suicide or medical emergency”, Kupers said. “If he was enough at risk to warrant in-cell video monitoring, why was nobody monitoring the video and intervening?”

The prison’s failure to adequately monitor Robinson’s cell may have contributed to his death, Kupers said.

“Lots of people have heart attacks, most people survive due to prompt medical intervention,” he wrote. “He died during a four-hour interval, where he was inadequately monitored, and it is very possible that had his immobility and slumping been noticed by staff and had a code been called, his life would have been saved.”

‘A set-up for an almost inevitable heart attack’

The autopsy noted that Robinson was a diabetic who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and suffered from psychosis. The toxicology report found several antipsychotic drugs – olanzapine, and two types of risperidone (the generic version of Risperdal) – in his system.

Kupers raised another issue that he said suggests negligent treatment by the prison staff. He says Robinson appeared to have metabolic syndrome, which is common in people who take antipsychotic drugs. It can cause obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes and hypertension, leaving people vulnerable to heart attacks, said Kupers, who noted he did not have access to Robinson’s clinical chart or custody notes.

“Being alone in a prison cell with high starch, poor quality diet, and getting little exercise, worsens the metabolic syndrome,” Kupers said. “He was a set-up for metabolic syndrome and diabetes plus an almost inevitable heart attack or stroke.”

Kupers also questioned whether the prison had given Robinson proper care addressing his mental health struggles: “Was he provided inadequate mental health treatment, given the severity of his mental illness, where he was provided insufficient or zero psychotherapy, case management and rehab opportunities, and left to vegetate in a cell taking antipsychotic medications?”

Did Robinson even need antipsychotics? Robinson’s family and friends deny he was bipolar or psychotic although prison conditions and fighting his long sentence left him depressed. His cousin, Darlene Morris, believes he was being medicated for things he didn’t have.

“He explicitly told me that,” she told MindSite News. “They just kept making it seem as though he was worse than he was. He knew he was depressed. All that stuff was getting to him, but then he would pull himself up.”

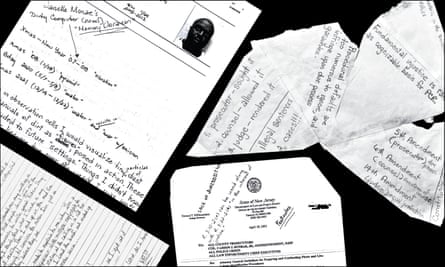

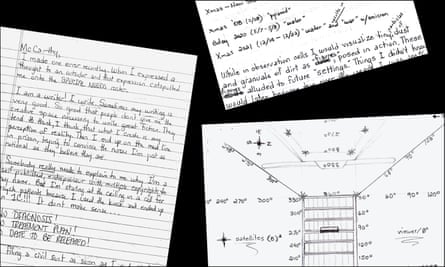

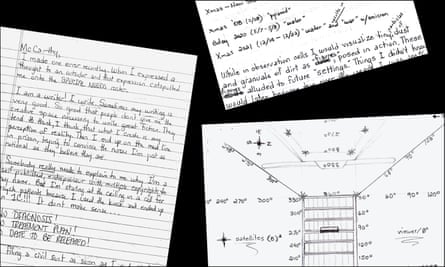

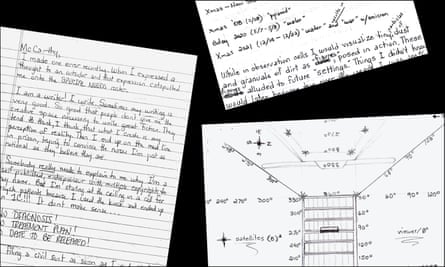

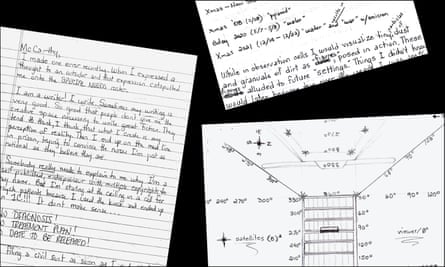

Robinson apparently shared that opinion. A package he sent to Morris, received about a week before his death, included a letter, written in neat handwriting on a page of yellow legal paper, addressed to someone named McCarthy. In it, Robinson expresses his belief that he was being treated as a psychiatric patient because of his writing.

“I am a writer! I write,” Robinson’s note says. “Sometimes my writing is very good. So good that people don’t give me the creative space necessary to write great fiction. They tend to think, I think, that what I create is my perception of reality. Then I end up on the med line in prison trying to convince the nurses that I’m just as rational as they believe they are.”

He ended the note with a plea:

“WTF am I taking RISPERDAL for?! What do I have?

“SOMEBODY NEEDS TO TALK TO ME!!!”

New Jersey prisons violated solitary rules, report says

Without public records or answers from the department of corrections, it’s impossible to pinpoint the reason for Robinson’s stay in solitary confinement, or how long he spent there. But the report from the ombudsperson shows some concerning patterns.

New Jersey administrative code bars inmates housed in these units from being confined in a cell for more than 20 hours per day. Yet more than 96% of people held in isolation units at New Jersey State Prison and three others said they spent less than two hours a day outside of their cells, according to the report.

Stays in these units can be up to a year, but the majority are less than six months, according to the report.

Those suffering from mental health issues are likely to end up in solitary confinement because prisons and jails lack the skills and personnel to properly care for them, according to a 2015 report from the American Friends Service Committee, which collected testimonies from inmates in isolation in New Jersey prisons.

Experts characterize long-term isolation as torture that causes psychosis, depression, anxiety, paranoia and hallucinations. In isolation, people with no history of mental illness may experience symptoms for the first time. It also may exacerbate the symptoms of those with such a history, according to the report.

In a statement responding to the ombudsperson’s report, the New Jersey department of corrections said it maximizes out-of-cell time by providing access to outdoor recreation, educational and vocational classes, social services, access to communication, showers, health services and religion services. Many incarcerated people refuse the programs offered, the statement said.

The ballad of Lil Eddie

By the time Shawana Gatlin and Robinson met, he was living with his mother in another subsidized housing development and writing about the Alabama Projects days in a journal, which Gatlin said was destroyed after a flood in her garage.

He had a street code, she added – but was no angel. He would tell stories about robbing drug dealers and befriending the women and girls in the projects, she said – like a real-life Omar Little, the Robin Hood-like character made famous in HBO’s The Wire.

“They would always look to him like he was their brother because he would always protect them from the older men, who would try and mess with them and touch them,” Gatlin said.

“He felt like ‘I’m not going to rob older women, we’re not going to rob men or people who work hard for their money. I’m going to rob [the dealers] because they take from other people,’” she added. “That was his way of rationalizing what he was doing.”

In 1995, Gatlin moved to Baltimore for school. He would visit her sometimes, and she would come back to Jersey to see him. Eventually, he was spending time in Baltimore regularly – but the street life beckoned him back to Paterson.

“If you go back up there, you’re not coming back,” Gatlin told him.

Three shots, life in prison

According to family and friends, Robinson returned to Paterson in April 1996 to stand up for his teenage brother after some older guys from the neighborhood jumped or threatened him.

Days later, he called Gatlin back and told her he had shot somebody and the man was dead.

“Eddie had an issue with anybody really bothering his family or anybody that he really cared about,” she said.

According to a case summary released by a New Jersey appellate court, Robinon’s brother got into an argument with another man, Lee Griffin, in April 1996 that resulted in a shoving match. His brother left the scene, but returned with Robinson and confronted Griffin. A crowd gathered, Robinson pulled out a gun and shot Griffin three times as Griffin ducked for cover behind a van, killing him. Robinson would later testify at his trial that he opened fire out of fear of the crowd.

The district attorney pushed for and won a first-degree murder conviction. The judge in the case called Robinson’s act “an execution” and on 5 May 2000, sentenced him to life in prison, with no possibility of parole for 35 years.

Gatlin attended the trial every day and went to see him weekly. While he was in jail and prison, they talked almost daily over the phone. For years, she would take the 70-minute drive to visit him every weekend.

Her visits left her perturbed. Prison officials often deprived him of food and placed him in solitary confinement, she said, punishments she described as human rights abuses.

“If he complained about something, the next thing you know he’d be in solitary,” she said.

In the early 2010s, she said she raised so many objections, she was banned from visiting the prison. She continued to write and call him regularly and to work on writing projects with him, however.

The homegoing

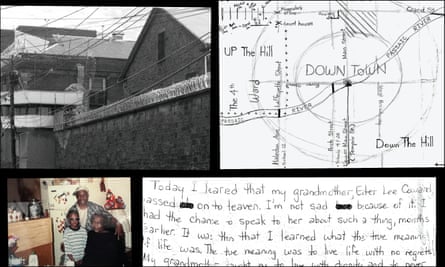

Morris, his cousin, didn’t think much about it when she received a hefty manila envelope postmarked 8 December 2022, eight days before Robinson’s death. A few days earlier, she had received another letter that recalled an uplifting conversation, the last one they ever had. Then it veered off into his thoughts about politics and an Afrofuturist reality, as much of his writings do.

Alone, the 2 December letter to his cousin is difficult to decipher – though the pages are clearly numbered and the writing in pen is in his customarily neat hand. He explains a legal motion claiming his attorney was ineffective in his representation. He switches to pencil and, later, highlighter.

On page 5, he references a picture of him as a child wearing blue sunglasses as he’s embraced by his father and great grandmother. He compares himself to Ryan Coogler, the Black producer credited for the blockbuster Black Panther films and Fruitvale Station, a 2013 movie about the police killing of an unarmed 22-year-old.

Morris would receive one more package before getting a phone call a few days later from the New Jersey department of corrections. The caller asked if she was his next of kin.

“I was wondering why they were questioning me the way they were,” Morris said. “Then they told me that he had passed away and I’m like: how? I just got a letter from him.”

Robinson’s homegoing was held at John B Houston Funeral Home in his hometown of Paterson. He was laid to rest in a blue and black button up shirt, surrounded by family members. Absent at the service, but mentioned in his obituary as a special love, was Shawana Gatlin. She received word of his death at the hospital as she sat with her father, who would die about a week later.

Gatlin continues to write and has published her own children’s books, including one called The Men in Blue about a 12-year-old boy who experiences police brutality and the friends who witness the incident. She makes a living writing copy for a bank, but said she has heard positive reviews from producers about the screenplay she had been working on with Robinson.

Gatlin was able to help Robinson publish one of his books – a crime thriller – but always considered his best writing to be in the journal destroyed in that flood years ago.

“I’m upset it was ruined because it really gave you a real good look at who he was on the inside,” she said. “He had a really traumatic childhood up until he passed. He really loved his family. And that was what landed him in prison.”

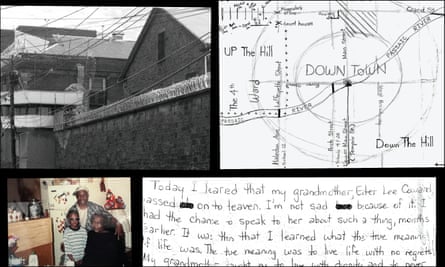

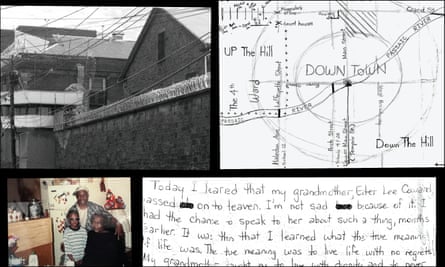

In 2017, after learning of the death of his grandmother, Ester Lee Coward, on New Year’s Day, Robinson used a scrap of toilet paper to write a tribute to her that now serves as his own epitaph.

“I’m not sad because of it,” he wrote. “I had the chance to speak to her about such a thing, months earlier. It was then that I learned what the true meaning of life was…My grandmother taught me to live life with dignity and to never compromise when you believe that what’s in your motives is true.”

-

Josh McGhee is an investigative reporter for MindSite News

-

Additional reporting by Kory McClary, Prison Journalism Project

-

This story is the product of a collaboration between the Prison Journalism Project, MindSite News and the Guardian US

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.