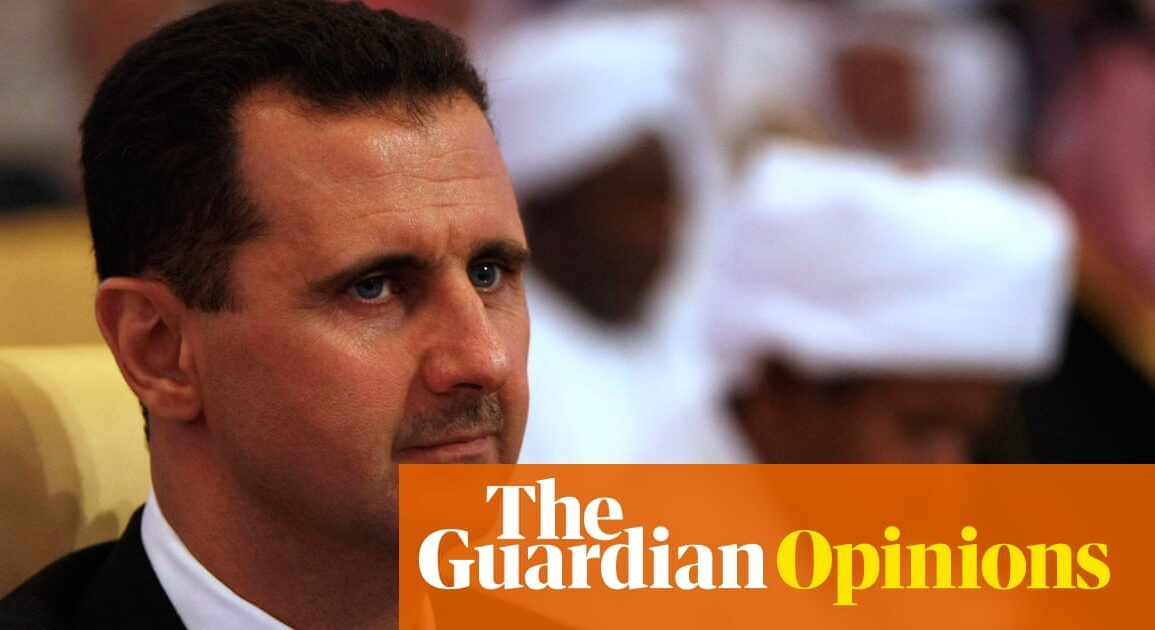

There are few regimes as cruel as the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad. There was seemingly no limit to what it would do to sustain his grasp on power, including dropping chemical weapons and barrel bombs on civilians in territory held by the armed opposition, and starving, torturing, “disappearing” and executing perceived opponents. The victims numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

Since December, Assad is gone, toppled by the HTS rebel group that now controls the interim government in Damascus. The leader of the interim authorities, Ahmed al-Sharaa, has promised a far more inclusive and rights-respecting rule. The jury is still out on whether he will live up to those vows, but one place where he has fallen short is in satisfying the Syrian people’s quest for justice. Both he and international courts could play a role.

Assad’s flight to Moscow has not diminished the desire for justice, nor should it. Vladimir Putin is much older than Assad and will not be Russia’s president forever. Just as in 2001 the Serbian government sent former president Slobodan Milošević to The Hague in return for the easing of sanctions, so a future Russian government may be persuaded to surrender Assad and his henchmen who joined him in exile as the price for, say, lifting sanctions or even maintaining Russia’s military bases in Syria.

Justice is always better if it can be provided locally, but for the time being, the Syrian judicial system cannot deliver. Under Assad, Syria’s courts mainly facilitated his extraordinary repression. They currently offer little hope of the fair and transparent trials that are essential for justice. Railroading people to conviction would only compound the Assad regime’s injustice, not remedy it. Most of Syria’s judicial system needs to be rebuilt from scratch.

For the foreseeable future, international courts provide the only realistic prospect of justice. One possible route would be for national courts to exercise universal or extraterritorial jurisdiction. That is possible because Assad’s crimes are so heinous that they fall within the category of crimes that are subject to global prosecution.

There already have been modest steps in this direction. Most involve Syrian perpetrators who happen to have fled abroad and been discovered. The most noteworthy was brought by German prosecutors in Koblenz against a Syrian intelligence officer who had run a torture center. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity. Yet so far the most senior perpetrators have not been detained, even though, since Assad’s fall, they are more vulnerable.

One government – France – has gone a step further and charged Assad himself for a particularly heinous crime, the use of a nerve agent, sarin, to kill more than 1,000 people in 2013 in Syria’s Ghouta region near Damascus. Trials in absentia are best avoided because, without the suspect present to defend himself, they do little to advance justice. But charges in absentia, with the aim of generating pressure for arrest, are laudable. More governments should follow in France’s footsteps.

But national prosecutions require a major investment by the prosecuting country, even assuming assistance from the body established by the UN general assembly to assemble evidence in support of such prosecutions, the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism. A more logical forum would be the international criminal court (ICC), where governments could pool resources in support of prosecution.

The ICC was absent in Syria during Assad’s reign. An effort by the UN security council to confer jurisdiction in 2014 was blocked by the Russian and Chinese vetoes. And with little prospect of securing custody of the most culpable officials while Assad retained power, the ICC prosecutor showed no discernible interest in pursuing other possible routes to jurisdiction.

Assad’s overthrow has changed that. Karim Khan, the current ICC chief prosecutor, has already visited the interim authorities in Damascus. But despite Assad’s litany of atrocities, no further progress is known to have been made. The fault lies in part with the new interim Syrian authorities, in part with Khan.

The easiest way for the ICC to secure jurisdiction would be for the new authorities to join the court and grant it retroactive jurisdiction. Acceptance of the court would be an important signal that they intend to respect Syrians’ rights, but al-Shara has not taken that step or indicated that he will. His reasons are not entirely clear.

One factor may be that he fears the ICC would prosecute him or fellow HTS commanders for human rights violations they committed in north-western Syria, which they controlled since 2017. This is not a trivial fear, but those abuses paled in comparison to the Assad regime’s atrocities, so it is hard to imagine they would be Khan’s priority.

Another reason may be that some of the foreign forces operating in Syria have signaled their displeasure with the prospect of ICC jurisdiction. Turkey, the principal backer of the interim authorities, may not want oversight of the territory it has seized in northern Syria. The United States, whose decision to maintain Assad-era sanctions presents the principal impediment to economic and hence political stability in Syria, undoubtedly doesn’t want scrutiny of its forces fighting the Islamic State in the northeastern part of the country.

Israel, whose officials already face ICC charges for starving and depriving Palestinian civilians in Gaza, clearly doesn’t want additional vulnerability for its ongoing operations in Syria. Even Russia undoubtedly opposes ICC jurisdiction, given the vulnerability of its commanders and even president Vladimir Putin to charges of bombing hospitals and other civilian infrastructure in north-western Syrian. They, too, already face ICC charges for their conduct in Ukraine.

Given these competing factors, there may be no overcoming the interim authorities’ reluctance to join the ICC, but that is not the end of the story. The ICC prosecutor on his own could establish jurisdiction over an important subset of the Assad regime’s crimes.

The key would be to follow the same strategy pursued in Myanmar. It has never joined the court, but adjacent Bangladesh has, which gives the court jurisdiction over any crime committed on the neighbor’s territory.

Although the ICC had no direct jurisdiction over the mass atrocities – murder, rape and arson – committed in 2017 against the Rohingya of Myanmar’s western Rakhine state, it did have jurisdiction over the crime of forced deportation because that crime was not completed until Rohingya stepped into Bangladesh. That became a backdoor method of addressing the atrocities that drove more than 750,000 Rohingya to flee. The court has approved that jurisdictional theory and is now considering the prosecutor’s request for an arrest warrant for the Myanmar army leader, Min Aung Hlaing.

Khan could do the same thing in Syria. Jordan is an ICC member and the Assad regime’s atrocities drove more than 700,000 Syrians to flee there. Charging Assad-era officials with this crime of forced deportation would be a way of addressing many of that regime’s atrocities. That partial justice would be far better than no justice at all.

This approach to jurisdiction would pose little threat to the interim authorities, whose cooperation Khan would need at least to conduct on-site investigations. Whatever their misdeeds in north-western Syria before seizing Damascus, they would have had little if anything to do with why people on the other side of the country fled to Jordan. Nor do any of the current international actors in Syria seem to be contributing to any exodus to Jordan.

Maybe Khan is secretly advancing this plan, but I doubt it. In the case of Myanmar, the ICC prosecutor’s office, beginning under Khan’s predecessor, Fatou Bensouda, publicly signaled that it was pursuing this approach. Khan has given no such indication for Syria.

He should. I am a strong backer of the ICC, but when I have defended it publicly, detractors commonly note its lack of action on Syria. For years, I defended the court by arguing that its lack of jurisdiction over Assad’s atrocities was not its fault. But with the forced-deportation route to jurisdiction now approved by the court for Myanmar, the decision whether to pursue it for Syria lies mainly with Khan. Assuming that the interim authorities continue to eschew court membership, Khan should exercise that option for jurisdiction. The people of Syria deserve it.

-

Kenneth Roth, former executive director of Human Rights Watch, is a visiting professor at Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs. His book, Righting Wrongs: Three Decades on the Front Lines Battling Abusive Governments, was published by Knopf and Allen Lane in February.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.