Timothy Reif’s voice is warm. Measured and steady. A bit quiet, but in a way that draws you in. “It starts in a very simple place,” he says, “and now I know so much more.” I’ve asked him a question he’s answered countless times over the past three decades: “When did you start looking for Fritz’s collection?”

This story, like most stories worth telling, begins simply. You almost need it to, or else you’ll lose faith, lose the kind of naïveté that lulls you into thinking you’ll get direct answers to relatively simple questions. But before it gets complicated — and it will —I’ll lay down the facts as I first came to know them: There is a drawing at the Art Institute of Chicago that once belonged to a man who was killed in the Holocaust, and now his family is accusing the museum of possessing art that was stolen by the Nazis.

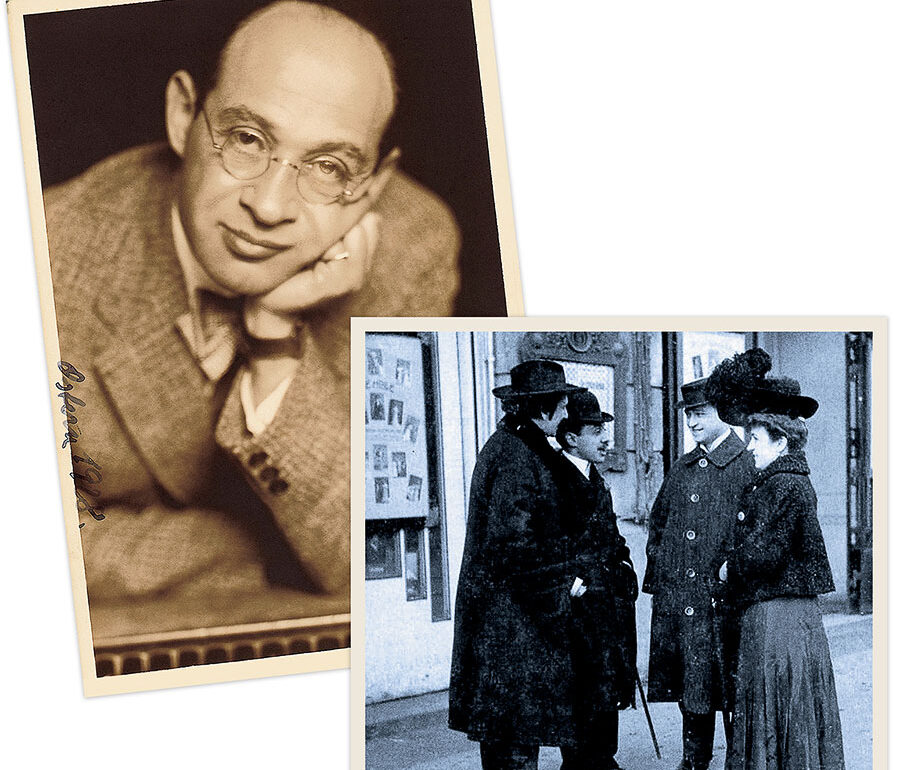

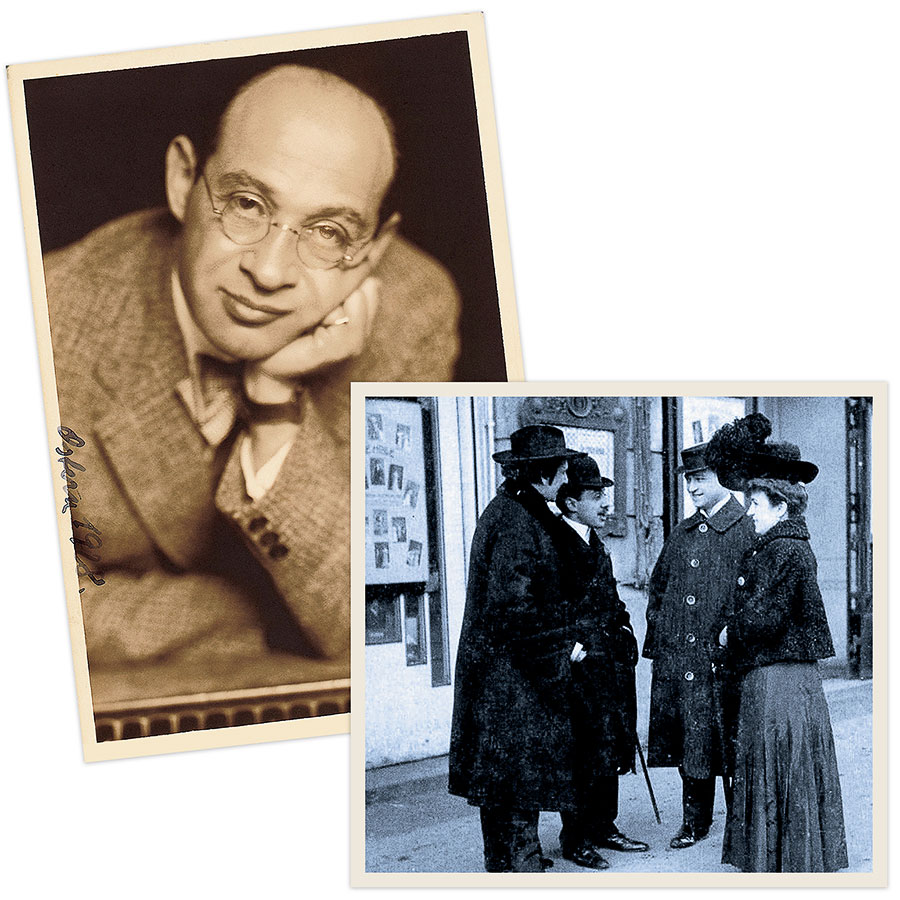

Reif, 65 and a federal judge in New York City, is one the legal heirs of Fritz Grünbaum, an Austrian actor, composer, and cabaret star who performed at legendary venues like Le Chat Noir and Kabarett Simpl during the early 20th century. He was also a voracious art collector and owned pieces by Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, Gustav Klimt, and, as an early appreciator of the Austrian expressionists, 80 drawings and paintings by Egon Schiele.

Jewish and a vocal critic of the Nazis, Grünbaum was arrested in 1938. By 1941, he was dead, the official cause a heart attack in Germany’s Dachau concentration camp. By 1956, pieces of his collection were for sale in a gallery in Switzerland, and by 1966 one work in particular, Schiele’s Russian War Prisoner, was in the Art Institute’s collection. Today, the drawing is worth $1.25 million.

But whether Russian War Prisoner will remain in the Art Institute’s possession is the subject of an ongoing legal dispute — and a quest for restitution that started in the 1990s, when Reif and his family began searching for Grünbaum’s collection: more than 400 pieces that had been scattered after the war.

In December 2022, the Antiquities Trafficking Unit of the Manhattan district attorney’s office began a criminal investigation into pieces from Grünbaum’s collection that would have been trafficked through New York City. By September 2023, the DA’s office had issued a seizure warrant for three Schiele drawings, including Russian War Prisoner, stating there was reasonable cause to believe that they were stolen property. (This followed the seizure and return of seven other works, including from the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.) In January, two of the drawings, previously in the collections of the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh and Oberlin College’s Allen Memorial Art Museum, were voluntarily returned to the family, even though both institutions maintained that they had lawfully owned them.

The Art Institute, however, holding fast to the same assertion, has refused to give up Russian War Prisoner. “We have done extensive research on the provenance history of this work and are confident in our lawful ownership of the piece,” the museum said in a statement. “Federal court has explicitly ruled that Grünbaum’s Schiele art collection was ‘not looted’ and ‘remained in the Grünbaum family’s possession’ and was sold by Fritz Grünbaum’s sister-in-law Mathilde Lukacs in 1956. If we had this work unlawfully, we would return it, but that is not the case here.”

Before I became intimately familiar with the details of this case, I assumed the truth would be obvious. Either the drawing had been stolen or it hadn’t, and if it had, the ethical thing to do would be to return it. But the more people I talked to and the more legal documents I attempted to parse, the more I realized that the dispute over Russian War Prisoner merely seems simple. And that the truth is far more complex.

The interwar period in Europe was chaotic. The 1920s and ’30s were a breeding ground for discontent and frustration. Inflation skyrocketed, economies crashed — but the arts thrived.

A lawyer-turned-performer who had been born and raised in what is now the Czech Republic and served in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, Grünbaum was a mainstay in the cabaret scene. If your only frame of reference for cabaret is the 1972 film starring Liza Minnelli, you’re not entirely off. Grünbaum was the inspiration for Joel Grey’s iconic master of ceremonies character, and while the movie takes place in Berlin, it offers an idea (though an exaggerated one) of the art form in Vienna before the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938: an untethered, wildly wicked world where cigarette smoke and Champagne mixed with art and politics.

It was Grünbaum’s wit, piercing and quick, that skewered the rising fascist establishment. During a power outage at a performance in 1938, he peered out into the darkness and declared from the stage: “I see nothing, absolutely nothing. I must have accidentally gotten myself into National Socialist culture.”

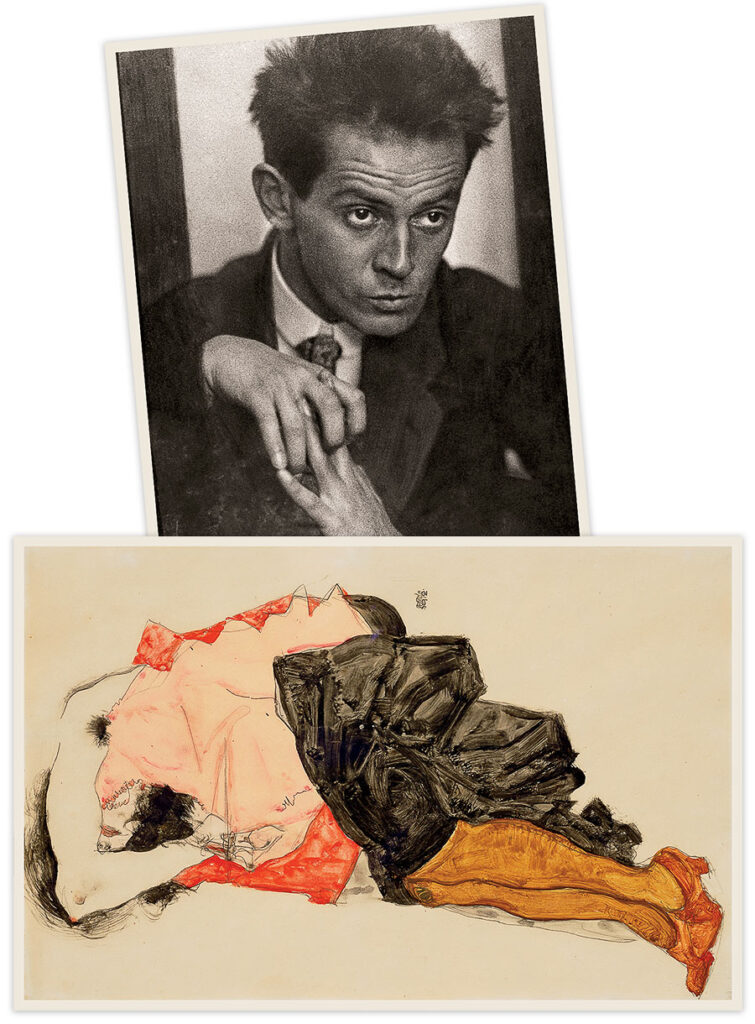

Like Grünbaum, the Austrian expressionists also pushed against what they saw unfolding during their lives — for Schiele, the complacency at the turn of the century and World War I. Schiele’s exaggerated line work and emotionally jarring color palette intentionally challenged conformity, and perhaps this is why Grünbaum was so drawn to his work. In 1928, Grünbaum, who had been lending out pieces of his collection, allowed an Austrian art dealer named Otto Kallir to borrow Schiele’s Russian War Prisoner and four other works for an exhibition. In the catalog, at Grünbaum’s insistence, all were attributed to the “Fritz Grünbaum Collection.” Though no longer practicing law, he had a lawyer’s sensibilities and an appreciation for what he had. Schiele, who died in 1918 from the Spanish flu at age 28, was nowhere near as popular as he would later become, but Grünbaum took his collection seriously. He was drawn to Schiele’s distorted figures, to their unflinching gaze. He made space for their evocative imagery.

If your only frame of reference for cabaret is the 1972 film starring Liza Minnelli, you’re not entirely off. Grünbaum was the inspiration for Joel Grey’s iconic master of ceremonies character.

“I’m thinking of him going around his apartment,” Reif says. “There would be a lot of going back and forth looking at [the Schiele pieces]. Those eyes looking back at him, prompting thoughts, emotions. Some degree of discomfort.”

Russian War Prisoner is relatively tame compared with other works by Schiele. One of many drawings done by the artist during his military service, it was never formally titled. This is the case for most of Schiele’s pieces, which makes finding them difficult, especially if you’re looking for something that you think has been stolen. Every collector, gallery, institution, seems to have its own name for the same Schiele drawing or painting, usually one that reads more like a general description: Young Boy. Seated Woman With Bent Knee. Semi Nude, Back View.

Called Russian War Prisoner in the Art Institute’s catalog, this 1916 drawing has been titled every combination of war, soldier, and Russian. It is one of a series of drawings of Russian prisoners of war that Schiele completed while stationed with the Austrian army at a POW camp in Mühling, Austria, during World War I. Shown in partial profile, its seated subject, Grigori Kladjishuli (his apparent name is written in Cyrillic on the upper right side of the piece), looks up at the viewer with war-weary eyes, his eyebrows arched and his right cheekbone cutting a sharp line across his face, which, along with his hair and hat, is rendered in color; the rest of his body descends down the page in delicate graphite lines.

The drawing was part of Grünbaum’s collection when he was arrested in Vienna just weeks after the Anschluss, after attempting to flee to neighboring Czechoslovakia. He was held in a police prison before being sent to Dachau, then to Buchenwald, then back to Dachau, where he died on January 14, 1941, at the age of 60.

Weeks earlier, on New Year’s Eve, Grünbaum gave his final cabaret performance, telling the audience, his fellow prisoners at the camp: “I beg of you, Fritz Grünbaum is not performing for you, but instead it is the number 57770 who just wants to spread a little happiness on the last day of the year.”

Within the Art Institute of Chicago’s prints and drawings collection, along with Russian War Prisoner, is Landscape With Smokestacks, a small pastel over monotype by Edgar Degas. It’s a beautiful drawing, notable because of the artist but also because of its role in jump-starting the restitution of Nazi-era art in the United States. The piece was from the collection of Friedrich and Louise Gutmann, a Dutch Jewish couple and heirs to the Dresdner Bank fortune. They were arrested in 1943 and later killed in concentration camps — Friedrich beaten to death at Theresienstadt for not signing over what remained of his family’s collection, Louise gassed at Auschwitz. Simon Goodman, their grandson, discovered the existence of his family’s lost art only after his father’s death in the early 1990s. Landscape With Smokestacks was the first piece he found, in the collection of pharmaceutical heir Daniel C. Searle.

The piece was on loan at the Art Institute almost immediately after it was purchased by Searle, a trustee of the museum. Goodman and his family sued him in 1998, and as part of the settlement, which divided ownership of the painting equally between the two parties, the Art Institute purchased the piece for its appraised value of $487,500. Sort of: Searle donated his half to the museum in return for a tax write-off. Goodman also insisted that the museum add the Gutmanns’ names to the exhibition plaque and catalog, the omission of which he felt was unconscionable. “It seemed to add insult to injury,” he told me in an email. “Not only had they been murdered, but then their history had also been eradicated!”

A few years later, the Art Institute announced that it had scheduled an exhibition on Nazi art looting for the summer of 2003. But in January of that year, to the surprise of its contributors, the show was canceled abruptly. The museum didn’t publicly explain why, but the complexity surrounding provenance seems to have had something to do with it.

The meticulous documentation of forced sales of art by Jewish owners to the Nazis created a confusing veneer of legality after the war. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws had been established to strip Jewish people of basic rights; by 1937, the Nazis had started requiring Jews to declare and register their property. Ultimately, this led to the confiscation and seizure of art, often masked by forced sales and empty promises: “Give us your art and” — in the case of the Gutmanns — “we’ll give you a train ticket out of Nazi Europe.” But, of course, it never went like that. And all that remained was a record that implied decision-making autonomy by the sellers, when in reality their lives had been at stake. In many cases, the proceeds from a sale were put into a bank account that would, in the end, be frozen.

“My dad and his sister were told, ‘You’re so lucky to be alive,’ ” Goodman says when I ask why his family waited so long to try to get their art collection back. “This concept of a forced sale wasn’t really accepted by the art world until recently.”

It’s a small but important distinction at the heart of restitution cases like these, like the one involving Russian War Prisoner. If you sell priceless art with the proverbial gun to your head as a means of survival, does it really count?

There was an attempt, toward the end of the war and immediately after, to make sense of the messiness and return art to its rightful owners. The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program, its personnel colloquially known as the Monuments Men (the inspiration for the 2014 film of the same name), was established in 1943 as a specialized force within the military that focused on recovering looted art.

In 1947 and 1950, the State Department sent letters to museums, libraries, and other cultural institutions, including the Art Institute, advising them that “the continued vigilance of American institutions and individuals in identifying cultural objects improperly dispersed during World War II is needed.” (The Art Institute says it has no record of receiving such a warning.) And yet, art was lost, some of it for decades. In the war’s immediate aftermath, survivors and their relatives were simply trying to sift through the wreckage of their lives.

There was all this stuff floating out there, nobody knew who owned what, and people were broke, hungry even,” Goodman says. “It’s too easy to imagine the temptation to sell something. You tell yourself, ‘He’s not coming back, is he?’ ”

Timothy Reif never knew Fritz Grünbaum, a cousin of his paternal grandfather’s, but he was introduced to him by way of a nickname. “My little Fritz Grünbaum,” Reif’s grandmother would call him as a young boy, when he’d run around her New York City apartment with his brother, putting on plays for the family.

“I think there was something about my mischievous nature that reminded her of Fritz,” Reif says. “And I knew from her expression and tone of voice that it was an honor. I knew that my grandmother loved someone very much and was kind enough to call me after him.”

Grünbaum, who died childless, had also been close with Reif’s father, composer Paul Reif. As musicians in Vienna, they had both worked in the theater and were collaborators, writing operettas together before the war.

Years later, a cousin of Timothy Reif’s discovered their grandmother’s journal. On thin, brittle paper in careful German handwriting were what seemed to be excerpts from Fritz’s routines and lyrics that he had composed. “My grandmother wrote about him,” Reif tells me, “because she feared that only she and her family, her sons and daughter, would remember him.”

After the Anschluss, Reif’s grandmother, realizing her family had to leave Austria in order to survive, transferred the ownership of her successful dress shop to a non-Jew (a practice then known as voluntary Aryanization) and, with Reif’s father and aunt, fled Vienna. They eventually made their escape from Europe by way of Scandinavia. His grandmother secured passage on a ship that left Norway on April 7, 1940, two days before Germany invaded, while his father and aunt made their way to Haiti. The brother and sister spent a year waiting for their U.S. immigration quota numbers to clear, then joined their mother in New York City in 1942.

By the 1950s, Reif’s grandmother had opened a new dress shop, on Central Park South, and every week the family — small but close — would gather in her apartment for Sunday dinner. It’s easy to imagine the quiet comfort of such a meal. A sense of tranquility after years of unrest and uncertainty; the poignancy of a grandmother watching her young grandsons and remembering whom she’d lost.

It’s a small but important distinction at the heart of restitution cases like the one involving Russian War Prisoner. If you sell priceless art with the proverbial gun to your head as a means of survival, does it really count?

There were also things that weren’t discussed. Silence, as it was for so many survivors of the war, was the only way to manage the toll of what had happened. “I heard things that I didn’t understand around the dinner table,” Reif says. “There was not a lot expressly said when I was growing up about what my dad, my aunt, my grandmother, had lived through.”

Reif’s grandmother died in 1974. His father died four years later — but not before trying, unsuccessfully, to find out from Otto Kallir, by then an established gallerist in New York, what had happened to Grünbaum’s collection after his arrest. In 1992, Reif and an uncle saw an ad for one of Grünbaum’s Schiele pieces for sale at a gallery in Vienna. They wrote to Jane Kallir, Otto’s granddaughter and a renowned Schiele expert, asking her to be their eyes and ears during the sale. And a few years after that, Reif stood with his mother, Rita, at the MoMA in front of a different Schiele: Dead City III, a rare painting by the artist that had also been owned by Grünbaum, now on loan from the Leopold Museum in Austria. The full scope of what had been lost finally set in.

Rita, the antiques and auctions columnist for the New York Times, knew that challenging the ownership of a piece from the Leopold Museum was a big deal, but it also was intensely personal. “My dad had seen it in Fritz’s apartment and it had an impact on him,” Reif says. “Dead City III was important to my father. He was gone, so my mother decided to step forward.” The 1998 seizure of the painting by Manhattan district attorney Robert Morgenthau on behalf of Reif’s mother began the fight to reclaim the rest of Grünbaum’s collection.

The family’s efforts have gained momentum in recent years, amid increased public scrutiny of stolen art and antiquities. In 2014, the Schiele watercolor Town on the Blue River was sold by Christie’s auction house under an acknowledgment that Grünbaum was a previous owner (as part of a restitution agreement, the heirs were compensated). In 2022, two additional works — Woman Hiding Her Face and Woman in a Black Pinafore — were returned to the family by a London-based art dealer after a lengthy legal proceeding. The heirs prevailed with help from the 2016 Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act, which instituted a new national statute of limitations for the restitution of Nazi-confiscated art. By 2023, a series of lawsuits had been filed against various collectors and institutions, including the Art Institute, in an attempt to recover roughly a dozen more Schiele artworks.

It has been a seemingly endless back-and-forth of rulings, filings, and appeals as each party makes its case for rightful ownership. Restitution, in general, is fraught because it requires returning a work to its original owner, usually without compensation. The criminal investigation brought by Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg is ongoing, but in November 2023 the Southern District of New York granted the Art Institute’s motion to dismiss Reif’s lawsuit. And in February, a federal judge reaffirmed the museum’s legal ownership of the drawing in the same civil case. (The heirs are appealing.) While those rulings are separate from Bragg’s investigation, it was a frustrating setback for Reif.

When I ask why he thinks the Art Institute is continuing to fight back against the family’s claims, Reif gets quiet again. “I …” He pauses. “I don’t know why.” I can sense the fatigue in his voice. “It’s 2024. We’re now 83 years after his murder. The facts are — to say they’re pretty clear is a great understatement.”

This civil case, and others like it, is characterized by technicalities. Legal concepts like laches (an unreasonable delay in making a claim) and collateral estoppel (a rule against relitigation) have been cited in decisions regarding Grünbaum’s collection. These are complex legal doctrines that necessarily affect older claims. And they inevitably make the issue feel needlessly complicated and confusing, even when — especially when — Nazi-era looting is involved.

I think of what Goodman told me when I asked him why restitution is worth fighting for. “The art is one of the few things to have survived. Everything got stolen, everything went, but the art, amazingly, carries on.” It can’t help but be personal because, as Goodman puts it: “Art is immortal.”

Legal technicalities aside, the question at the heart of the dispute hanging over Russian War Prisoner — over the entire Grünbaum collection — is whether the entertainer’s artwork can be considered stolen by the Nazis. The answer depends on whom you ask. “It’s not clear,” says DePaul College of Law professor Patty Gerstenblith, an expert in both art and museum law and cultural heritage law. “The plaintiffs have their version of the facts. The Art Institute has different versions of the facts.”

Before the stories diverge, however, there are a few aspects that are generally agreed upon: that notable Swiss art dealer Eberhard W. Kornfeld sold 20 Schiele pieces, including Russian War Prisoner, to Otto Kallir in 1956 for 13,270 Swiss francs (roughly $3,093, or nearly $36,000 today); that Kallir, by then firmly established in New York City, used pieces from this sale to host the first exhibition of Schiele works in the United States, increasing the international popularity of the artist; and that Kallir ultimately sold pieces from the Grünbaum collection to various galleries and collectors. By 1966, Russian War Prisoner had made its way to Chicago’s B.C. Holland Gallery, which then sold the drawing to the Art Institute for $5,500.

What is being contested is what happened between 1938, the year of Grünbaum’s arrest, and 1956, when pieces from Grünbaum’s collection, including Russian War Prisoner, appeared in Kornfeld’s gallery. The Art Institute believes with certainty that after Grünbaum’s wife, Elisabeth, died in 1942, his sister-in-law Mathilde Lukacs took lawful possession of the collection and sold it to Kornfeld after the war.

Grünbaum’s heirs disagree. Here is their version of the facts:

On March 10, 1938, after Hitler declared the imminent “liberation” of Austria, Fritz and Elisabeth attempted to flee to Czechoslovakia but were recognized and turned away at the border. This is not in dispute. And neither is Fritz’s arrest on March 22, which led to his deportation to Dachau.

Elisabeth, still in Vienna and hoping for her husband’s eventual release, did her best to comply with the laws concerning Jews that were being rapidly put into place in Austria. On April 26, the Nazi government passed the Order for the Disclosure of Jewish Assets, requiring every Jew in both Germany and Austria to register any property or assets valued at more than 5,000 reichsmarks (nearly $45,000 in today’s dollars). In order to do so for her imprisoned husband, Elisabeth requested and was given permission to have him execute a power of attorney granting her control over his assets.

But according to a February filing from the Manhattan DA’s office, even though there is documentation that Fritz Grünbaum transferred power of attorney to his wife, there are also considerable issues with how this could have happened — if it even did. The 160-page filing, which argues that the Art Institute is obligated to turn over Russian War Prisoner, was authored by Matthew Bogdanos, the assistant district attorney who leads the Antiquities Trafficking Unit, which has recovered more than $410 million worth of stolen items from the ancient world since it was launched in 2017. Along with highlighting inconsistencies concerning key dates, Bogdanos questions how a Jewish woman could have made a 250-mile journey, alone, across the German-Austrian border and gained access to her imprisoned husband in order for him to sign legal papers. Plus, neither Grünbaum’s nor his wife’s signature shows up on the documents — only the Nazi-approved notary public’s signature does.

On August 1, 1938, Elisabeth submitted Fritz’s declaration of assets to the Property Transaction Office, along with the required inventory and appraisal, which had been conducted by a Nazi-approved art historian, Franz Kieslinger. There is no evidence of Grünbaum selling any of his Schiele pieces before 1938, and Bogdanos insists we can assume Russian War Prisoner was part of this inventory. Grünbaum’s entire collection was valued at 5,791 reichsmarks.

While wonky and cumbersome, these legal details continue to prove a point: that the complexity of these cases doesn’t lie in the overarching, well-known themes of the Holocaust but in the minutiae and in the paperwork. There is documentation that Grünbaum signed over power of attorney to his wife, but did he really? And if he did, does doing so while imprisoned constitute a voluntary signature?

Elisabeth was arrested on October 5, 1942, and deported to the Maly Trostenets extermination camp near modern-day Minsk, Belarus. But before that, in this version of the facts, she had moved Grünbaum’s entire collection (once again meticulously inventoried, this time by Otto Demus, an employee of the Central Office for Monument Protection) to Vienna’s Nazi-controlled Schenker Warehouse to await Grünbaum’s release. Between 1938 and her 1942 deportation, Elisabeth moved four times within Vienna. According to Bogdanos, there is no record that she reported any movement of personal property, like her husband’s collection. In the meantime, Elisabeth’s sister Mathilde Lukacs and her husband would have fled Austria for Belgium, where they were later imprisoned, without ever taking possession of Fritz’s art.

In 1955 and 1956, 70 pieces from Grünbaum’s collection, including Russian War Prisoner, mysteriously appeared in Kornfeld’s gallery. In a 2007 deposition for a separate case, Kornfeld produced, for the first time, letters and ledgers that detailed Lukacs’s ownership and sale of the artworks to the gallery. Bogdanos contends that those documents — specifically the ledgers — were forged decades after the alleged sales. (Kornfeld died last year.)

Gerstenblith, who has followed this dispute closely, also questions Lukacs’s involvement. “When I thought it was one piece, I thought maybe the sister-in-law could have smuggled this one drawing in her purse,” she says, referring to an earlier, separate case from 2005 that involved Grünbaum’s heirs, a private collector, and Schiele’s Seated Woman With Bent Left Leg (Torso). But as more and more Schieles from Grünbaum’s collection have been discovered, and more lawsuits filed, she’s reconsidered her stance. “Now that I know we’re talking about 10 to 15 pieces, I don’t know how she’d get them out of Austria.”

In 2017, Kornfeld admitted that Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of Hitler’s personal art curator, had become an important client after the war. He had sold art on Gurlitt’s behalf and even visited Gurlitt’s apartment. There he would have seen the vast collection of art that Gurlitt had inherited from his father, who specialized in confiscating pieces by artists that the Nazis deemed degenerate — artists like Schiele. In 2012, German customs officials found more than 1,500 works in Gurlitt’s apartment. From whom might Kornfeld have bought Russian War Prisoner if not Lukacs? Bogdanos points to Gurlitt.

Grünbaum’s family also alleges that Kallir knew when he purchased the Schieles from Kornfeld that they had belonged to Grünbaum, citing the 1928 exhibition for which Grünbaum had lent Kallir Russian War Prisoner. “Of all the people connected to this case across decades and continents, one person beyond all others knew that the Russian War Prisoner displayed in Galerie St. Etienne [Kallir’s gallery] in New York in 1957 was the same Russian War Prisoner that had once belonged to Fritz Grünbaum,” Bogdanos writes in his filing.

With this particular detail comes a sense of betrayal — not just in the filing, but in Reif’s voice when he talks about his father trying to figure out where Grünbaum’s collection could have gone. “My dad was aware as a young adult that Kallir had known Fritz,” he tells me. “And through all these years [until his death in 1978], my father knew nothing. And Kallir told him nothing.”

On April 23, my inbox notification pinged. I’d been obsessively checking my email for days, and it had finally arrived: the Art Institute’s response to the Bogdanos filing, submitted to the New York State Supreme Court. I had been promised something beyond legal technicalities — facts and evidence, a new narrative to consider. And there it was.

The 132-page filing raises a number of technical points, but it also argues that while Fritz and Elisabeth Grünbaum didn’t survive the Holocaust, their art, jointly owned through marriage, stayed in the possession of the family — and that in 1956 the works were sold, lawfully, by Fritz’s sister-in-law Mathilde Lukacs to Eberhard Kornfeld. The Nazis, the Art Institute maintains, never seized Russian War Prisoner in the first place.

In this version of the facts, Fritz and Elisabeth and her sisters, Mathilde Lukacs and Anna Reise, began putting their possessions in storage not because of anything amounting to Nazi seizure, but because they were planning to leave Vienna. Upon news of the Anschluss, the three sisters and their husbands determined it would be best to join their brother Max Herzl in Belgium. Despite Fritz’s arrest in March 1938, the plan remained in place. Collectively, they decided to use Schenker Warehouse to facilitate the move. While the museum acknowledges the warehouse was “affiliated” with the Nazis, it also argues that the business provided legitimate storage and moving services to Jews, including Lukacs. Elisabeth, optimistic that Fritz would be released, remained in Vienna to wait for him, while both of her sisters, their husbands, and their property left the country.

The Art Institute’s position is unequivocal: “There is no evidence at all — none — that the work was ever physically seized by the Nazis.”

The museum agrees that two inventories were taken of the Grünbaums’ assets in 1938. But according to its response, the inventories were inconsistent — enough so that they could have represented different sets of assets. The Art Institute says there is no definitive proof that the Schieles assessed in Kieslinger’s detailed appraisal were included in Demus’s inventory, meaning the art was already elsewhere.

The Art Institute also maintains that any issue involving the power of attorney is merely a red herring — the art was marital property, so it doesn’t matter if the signature was coerced. But what the Art Institute filing doesn’t acknowledge is that in Austria, individuals retain their personal property after marriage. This is why Elisabeth needed Fritz’s signed power of attorney in order to register his assets with the government. Without it, Elisabeth had no legal rights to his property. But either way, the Art Institute argues that the heart of the matter is whether the Nazis physically stole Russian War Prisoner, and that there’s no proof they did.

According to the museum, the assets seized by the government after Elisabeth registered her husband’s property included only cash, bank accounts, and stocks, not his artwork. Elisabeth could have taken pieces from Fritz’s collection — highly transportable drawings and paintings — and secreted them away, giving them to her sisters for safekeeping in Belgium.

In the Art Institute’s filing, the paper trail relating to the Grünbaums’ property disappears in 1939, two years before Fritz’s death and three years before Elisabeth’s. The museum’s position is accordingly unequivocal: “There is no evidence at all — none — that the work was ever physically seized by the Nazis.”

But on June 9, 1941, Elisabeth, still in Austria, made her way to Vienna’s district court to register her husband’s death five months earlier. Fritz Grünbaum’s official registration of death simply states: “According to the deceased’s widow, Elisabeth Sara Grünbaum, there is no estate.” The heirs cite this as proof that the Nazis had already taken everything.

As for Kornfeld’s acquisition of Grünbaum’s collection, the museum maintains that the dealings were legitimate. In 1952, Mathilde Lukacs, answering an ad in a German newspaper, wrote to Kornfeld for the first time, according to the filing. Over the course of their business relationship, the dealer sold more than 100 pieces of art on behalf of Lukacs (their business relationship is not in dispute), but the Art Institute rejects Bogdanos’s suggestions that Kornfeld forged documents or lied about Lukacs’s sale of Grünbaum’s Schieles. There is no question the Schieles ended up in Kornfeld’s gallery, but the museum contends that if they had arrived as a result of Nazi looting, Lukacs would not have done business with Kornfeld for as long as she did; she would have recognized and questioned the pieces in the gallery’s exhibition catalogs that she had seen at the Grünbaums’ apartment.

And while Kornfeld may have sold Nazi-looted art on behalf of Cornelius Gurlitt, this occurred only after Gurlitt’s father, Hildebrand, passed away in November 1956, the museum asserts. Kornfeld’s Schiele exhibition, which included Russian War Prisoner, ran from September 8 to October 6, 1956. It would have been impossible for Gurlitt to sell Kornfeld the drawing, as Bogdanos suggests.

Nearly 20 years after the war, Russian War Prisoner was sitting in the B.C. Holland Gallery on West Superior Street when it caught the eye of Harold Joachim, the Art Institute’s curator of prints and drawings. In 1966, he proposed its acquisition by the museum. Joachim, himself a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, would have been intimately aware of the sensitivities surrounding postwar property disputes. And if so, the Art Institute maintains, how could he ever encourage the purchase of something that could have been looted?

The Art Institute, like the Manhattan DA’s office, presses into the details of Grünbaum’s story with precision, focusing on dates and documents that would suggest where new dots could connect. As with the Bogdanos report, these details provide the framework for a larger story, where, in this telling, a museum bought a piece of art that, despite the tragedy that befell its former owners, the Grünbaums had managed to protect.

When I started writing this story, I imagined I would walk up the steps into the Art Institute and maneuver around the front staircase toward the courtyard, where I’d take a left into the Modern Wing and an elevator to the third floor. Winding my way through the early-20th-century galleries, I’d find myself face to face with Russian War Prisoner.

I convinced myself that if I could see the piece in person, I’d also see Grünbaum — see a tangible expression of a more abstract inner life through the art he loved. Maybe I’d even ask Grigori Kladjishuli, the Russian war prisoner himself, how he’d gotten to Chicago.

That never happened. The drawing is so fragile that it has been on public display at the Art Institute only three times since its acquisition, most recently in 2011. But there is something poetically fitting about the piece being out of the public eye. There’s no easy way to see the drawing; there are no easy answers to the questions in the case of Russian War Prisoner.

The question I keep returning to, the one that I can’t shake, is if any of this truly matters. I know the answer is yes. That it matters if the collection was stolen or if it was lawfully sold to Kornfeld by Lukacs or if too much time has passed to do anything about it. But I can’t stop thinking about the simple truth that precedes all this complexity: that a terrible, tragic thing happened to innocent people. And if that terrible, tragic thing hadn’t happened, Grünbaum would have retained the agency to do what he’d like with his art.

The simple truths are often the hardest to acknowledge, and perhaps that’s why we make them complex. But what I know is that this story, as it seeks truth, is itself built on a series of simple truths: Art went missing. The people who know how Russian War Prisoner ended up in Chicago are now all dead. And the man who first loved the portrait, who hung it on his wall, was murdered. We don’t know definitively what happened between 1938 and 1956, and we may never know.

We try to hold ourselves together with legal frameworks and the scaffolding of reason and order, but the reality is that we are all stewards of a messy history.

It reminds me of a conversation I recently had with the Jewish writer Aviya Kushner, a former professor of mine at Columbia College. “In Judaism there’s a concept of hashavat aveda, of returning a lost item to its owner,” she told me. “We study the laws to determine if someone is the rightful owner, but what if what you’ve really lost is belief or hope? It might not be that you needed that lost scarf or that stolen painting, but when it was returned to you, your hope was restored.”

I think of Grünbaum, of the ways I imagine he made people laugh — how as the world changed and became unfamiliar, that laughter became its own kind of hope. It’s a lovely thought, despite the atrocities that were to come. And perhaps, as we make our way back to where we started, this is also where we end. Fritz Grünbaum is onstage. The audience is hushed in anticipation. The lights dim. We wait to see what happens next.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.