Richard Barnes remembers the first time he saw the cabin.

Transplanted from rural Montana to Sacramento, the wood structure stood out of place in the brightly lit storage facility. Measuring roughly 10 by 14 feet, the one-room interior was dark and claustrophobic, penetrable only by a door and two small windows. There had been no running water, no electricity, very little natural light. Whoever inhabited the cabin led a primitive life of near-total isolation.

That person was Theodore John Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber.

For decades, the cabin had housed both the instruments of destruction and the man who had wielded them. It was there that he lived in angry solitude, composing his 35,000-word anti-technology manifesto, and eventually launching a nationwide mail bombing campaign that would kill three and injure dozens, triggering an FBI investigation of historic proportions.

Once a sanctuary and laboratory for Kaczynski, the cabin had, since his arrest in 1996, become an object of public fascination and forensic importance. Barnes, the first and only journalist allowed into the warehouse, was there to photograph it.

The resulting photographs, which were published in the New York Times Magazine in September 1998 under the headline “Evil’s Humble Home,” would bring the cabin into full public view for the first time. In the accompanying text, novelist Richard Ford wondered what, if anything, the images could illuminate:

“Is random death more explicable when we can see its home base? Can we, armed with a picture rather than a thousand words, understand how a man made bombs to kill innocent strangers? Understanding always seems to be what’s needed when death comes out of nowhere. We survivors are said to ‘need’ to understand how it could happen. Or worse, how it could happen here. Maybe seeing is believing.”

On June 10, 2023, the 81-year-old Kaczynski committed suicide in prison, leaving behind little more than the cabin and an archive of his writings. Yet, the story lives on: His violence is remembered in the retellings of those who survived it, his anti-technocratic screed continuing to resonate for those dismayed by a world that seems increasingly threatened by the march of industry and technology.

Twenty-five years after Barnes took his photos, Kaczynski continues to cast a shadow over his life. Known by many as “the guy who photographed the Unabomber,” Barnes has found himself returning again and again to the cabin, his complicated feelings about its owner’s legacy, and how—if ever—art can bring closure.

An air of secrecy surrounded the assignment from the start. In early 1998, Barnes received a call from an editor at the Times. They wanted to see any architectural work in his portfolio, particularly of warehouses, though they wouldn’t explain why.

“That was what was so interesting, that they couldn’t tell me what it was,” Barnes recalls. “A few days later, they got back to me and said, ‘OK, are you familiar with Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber?’ And I said, ‘Of course I am.’”

Evan Jane Kriss, a picture editor at the magazine, remembers reading a blurb about the cabin being seized and stored as evidence in Sacramento. “It stopped me dead in my tracks,” she says. “I thought: ‘Imagine what that would look like.’”

From the Lincoln family’s mythic log cabin to Thoreau’s hand-built retreat on Walden Pond, the structure has become emblematic of a deeply held American belief in self-reliance and rugged individualism.

The assignment was simple but intriguing: Kriss wanted Barnes to photograph Kaczynski’s cabin in its new, enclosed environs. He agreed immediately.

For Barnes, 35 at the time, death and destruction were recurrent themes in his work. Here was an opportunity to look closely at an object that many said epitomized, in the oft-quoted words of Hannah Arendt, “the banality of evil.”

“The cabin is so loaded in terms of its references, in terms of Americana,” Barnes says. From the Lincoln family’s mythic log cabin to Thoreau’s hand-built retreat on Walden Pond, the structure has become emblematic of a deeply held American belief in self-reliance and rugged individualism. “Here’s the cabin in a completely different realm,” he says. “It’s a cabin that a person lived in who was creating bombs to go out into the world and kill people. And that, to me, was fascinating.”

Born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1953 and raised in Michigan, Richard Barnes ’79 ultimately moved to California for school. He took up printmaking at Foothill College before transferring to Berkeley in 1975 to study painting under Bay Area figurativists Joan Brown and Elmer Bischoff ’38, M.A. ’39. It was there that he found himself drawn to photography.

“One thing about photography is it allows you access in a way that being a painter in your studio does not,” he says. “I’m afraid of the studio, to be honest with you. I don’t like being alone, in my own head. I really like interacting with the world.”

Barnes explored photography in any way he could at Cal, transferring into the journalism department and taking photography classes in the College of Environmental Design, while also dabbling in history, rhetoric, and design. (“I was a Renaissance student,” he says, laughing.)

After graduating, Barnes traveled east to photograph traditional Japanese architecture and then to Egypt to shoot an archaeological excavation. The Times assignment just a few years later was in some ways a continuation.

“For me, archaeology and the act of excavation has always had a psychological component,” he says. “This was a perfect assignment for me.”

Photographer and subject had narrowly missed each other at Berkeley. Barnes matriculated into the university’s art department just six years after Kaczynski, an assistant mathematics professor, abruptly resigned. On May 25, 1978, one year shy of Barnes’s graduation, Kaczynski’s first mail bomb detonated at Northwestern University, injuring a campus police officer.

Kaczynski would go on to send 15 more homemade bombs, only two of which were diffused, targeting academics, geneticists, computer scientists, airline executives—people he deemed to be on the forefront of technological society and, thus, destroyers of nature.

He targeted his estranged campus twice. In 1982, electrical engineering professor Diogenes Angelakos came across what he thought was a construction tool near his laboratory in Cory Hall. A pipe bomb, as it turned out, the object exploded in his face and right hand. Angelakos survived and recovered from his injuries, but three years later, he was one of the first on the scene when a second bomb detonated in the same building, this time badly injuring graduate student and Air Force pilot John E. Hauser, M.S. ’86, Ph.D. ’89. Angelakos used a tie as a tourniquet to staunch Hauser’s bleeding.

The Unabomber’s terrorist campaign lasted another decade before the FBI finally apprehended him in his mountainside hideout and took it as evidence, along with its trove of books, writings, tools, and hardware. In an effort to protect it from snoops and vandals, lawyers requested to have the cabin moved from its original site outside of Lincoln, Montana, to a nearby Air Force base.

As the trial approached, the cabin became the focal point of his lawyers’ planned insanity defense. Only a madman, they argued, could have lived in such primitive conditions.

“I think it’s a good indicator of how far this Harvard [undergraduate] and Berkeley professor had fallen and how he was living and functioning,” Quin Denvir, one of Kaczynski’s lawyers, told a reporter in December 1997. “It says a lot about his mental state and who he was.”

The defense attorneys wanted to bring the cabin to the courtroom to show the jury (a replica wouldn’t have the same impact, they claimed). Kaczynski, for his part, adamantly defended his sanity and tried to dismiss his lawyers as a result.

In the end the trial never happened. In January 1998, Kaczynski pleaded guilty to all charges and was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Since the cabin’s arrival in California, no one from the media had been allowed to view or document it. Randy Turtle, president of SafeStore, the company contracted to transport and store the cabin, recalls being bombarded with requests.

“Everybody contacted us. The whole world contacted us,” she says. Though she’d promised to prohibit visitors, the query from the New York Times Magazine made her reconsider. With the lawyers’ approval, she gave Barnes the green light.

At the warehouse, Barnes found the cabin crowded alongside other evidentiary paraphernalia.

“It was surrounded by all this junk, if you will, all this stuff that the FBI was using in other cases,” Barnes recalls. “And I said, ‘This is not the place to photograph this. We really need to get it out of here, move it into another space.’”

Seeking a second opinion, Barnes enlisted his old friend and fellow Berkeley graduate, Dr. Scott Newkirk. After getting his MFA at Cal (’77), Newkirk had gone back to graduate school to study clinical psychology and, as it happened, decided to focus his dissertation on a “psychoanalytical study of the Unabomber manifesto.” Informed by their backgrounds in fine art and a shared interest in Kaczynski’s psychology, the pair returned to the storage facility for another walkthrough.

“Entering that warehouse was very visceral,” Newkirk remembers. “The light, the space, the kind of dark space, the scale of the cabin, … I was very interested in looking at the cabin to see what it was going to tell me about the person who made it.”

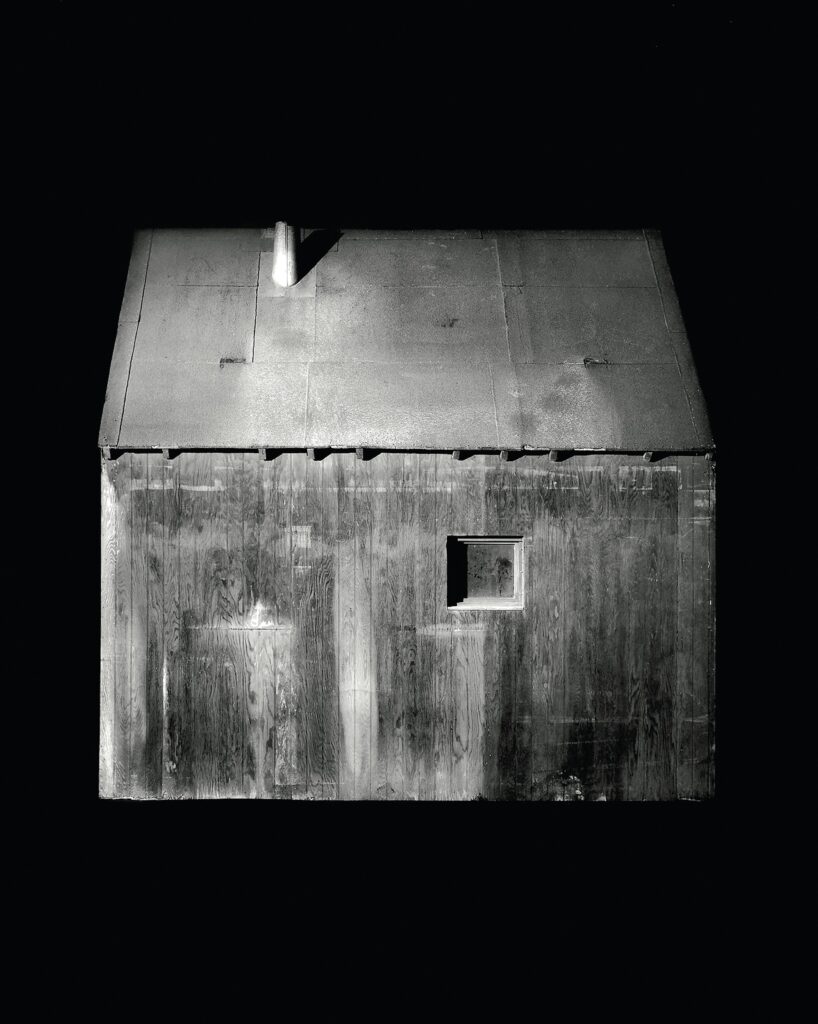

Newkirk immediately took note of certain telling details in the cabin’s construction. He pointed out the nails placed with militant precision, the wooden slats meticulously cut and pressed firmly together, the complete lack of insulation, and the two very small windows. From these observations arose conversations about Kaczynski’s mental health, comparisons with Thoreau’s beloved cabin at Walden, and musings about the significance of Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent and other anarchist literature found in the cabin’s vast library.

“I think the reason the cabin has become as iconic as it has is because it became the symbol, the proxy for [Kaczynski’s] mental state.”

James Oleson

Yet, as close as they stood to Kaczynski’s most intimate space, much remained hidden. The inside was completely off-limits, which only heightened Barnes’s curiosity.

“Anything that’s hidden, for me, is always kind of exciting,” he says. “This was akin to an excavation. I was excavating.”

Others shared his curiosity, a testament to the resonance of the cabin’s powerful iconography.

“I think the reason the cabin has become as iconic as it has is because it became the symbol, the proxy for [Kaczynski’s] mental state,” says James Oleson, J.D. ’01, an assistant professor of criminology at the University of Auckland who has written extensively about the Unabomber. The idea being: “If you look at the cabin, you see who Kaczynski really is. And he is a creature that is willing to live on the edge of society, but not in it; who although he could have running water chooses not to; although he could have sanitation chooses not to; although he could have electricity and refrigeration and lighting, he rejects those things.”

As the artist Julie Ault observed in her book Two Cabins, Thoreau’s spartan abode at Walden somehow represents a “paradisiacal homestead” while, “to most, Ted Kaczynski represents the dystopian pole of social isolation.”

Barnes knew he had his work cut out for him. Appearing in the magazine of record, his photos would reach a wide audience, defining—at least for a time—how the public viewed the cabin, and its owner.

The first step, he decided, would be to move it. Again.

With Turtle’s blessing, and “against all kinds of journalistic ethics,” he and his assistants propped the cabin onto four dollies and cut a hole in the wall big enough for it to fit through. “They let me do that. And I was just like, ‘Wow. That was a lot easier than I thought it was going to be.’”

The new room, in some ways, became the inspiration for Barnes’s photographic strategy. Completely empty, it looked at once like an interrogation space and an art gallery.

“And that fascinated me, with this kind of hinge between a piece of sculpture and this very banal sort of object that really connoted evil,” he says.

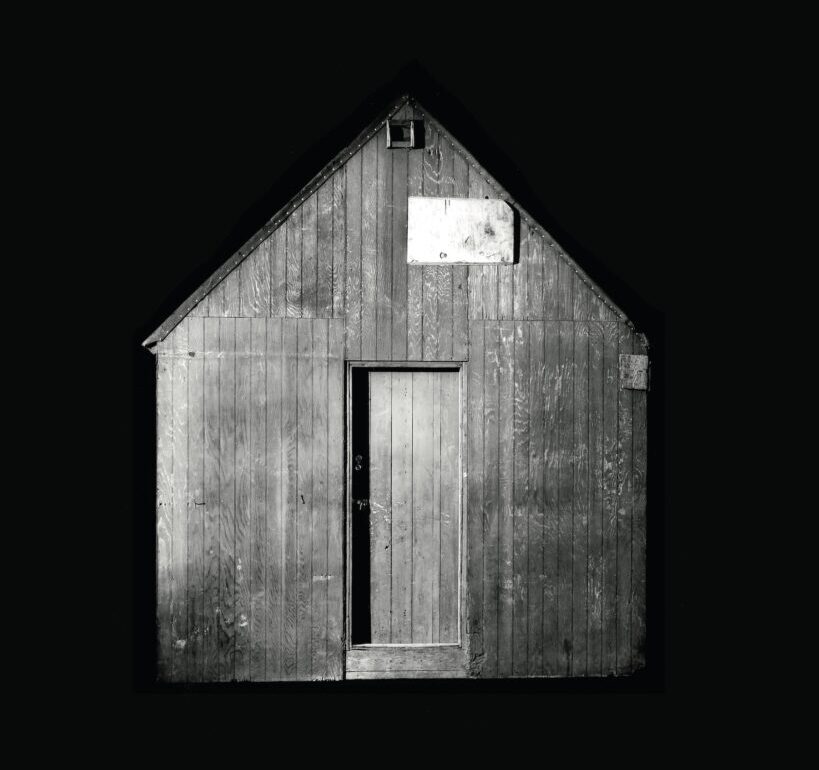

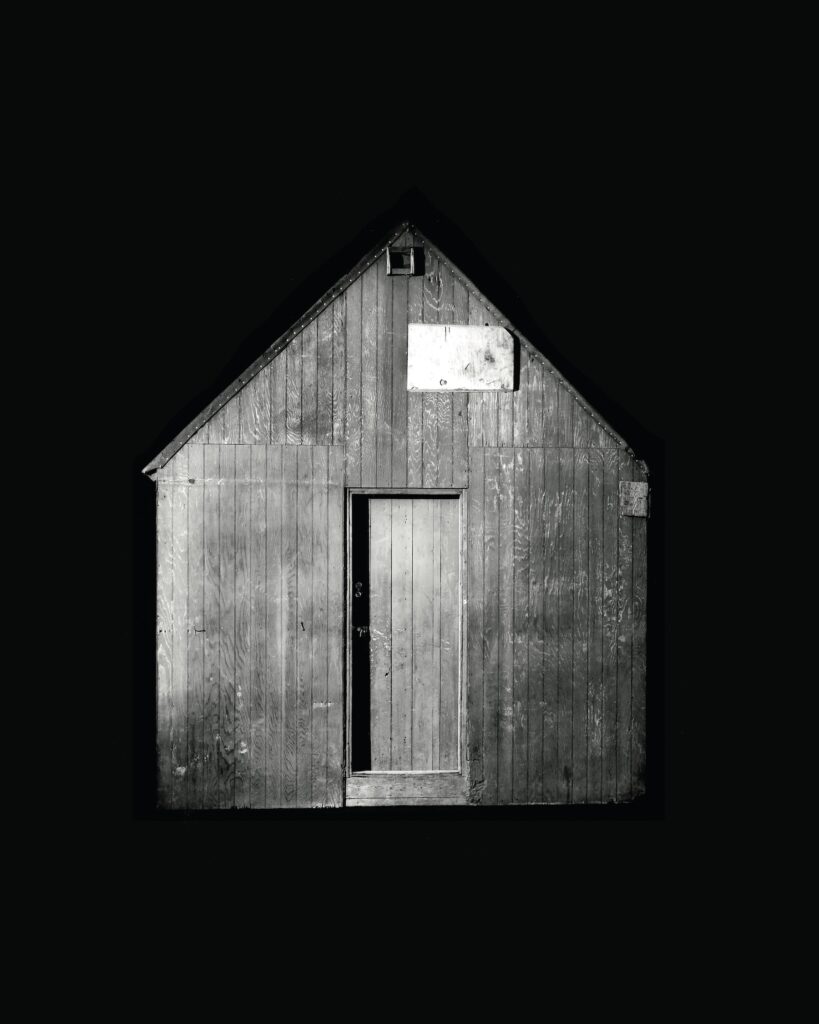

His first shot, “Unabomber Cabin, Sacramento, CA, 1998,” would become perhaps the most widely recognized, starting with the September 13, 1998, issue of the New York Times Magazine. The cabin—framed by support beams, industrial piping, and long fluorescent light fixtures—looks surreal and jarringly out of place, like a cardboard cutout of an oversized toy house. It scarcely seems to touch the ground. Only a faint shadow anchors wood to concrete. There is something eerily familiar yet disturbingly alien about the cabin in this light, a duality Ford would touch on in his accompanying essay.

In the photos, shot in black and white, the cabin is utterly decontextualized, a disembodied specter that seems frozen in time like a snapshot of Dorothy’s cabin hurtling away from Kansas.

“At best it’s an emblem, and not of evil’s banality—no, we know about that—but of evil’s humble beginnings, its embedded place in our landscape and past, its unobtrusive, almost neighborly nearness to us all,” he wrote.

Barnes wanted to push even further.

He was fascinated by the idea of architecture as evidence and wanted to put the cabin in dialogue with Kaczynski and his crimes. “And the way to do that, for me, was to photograph it from all four sides, like a subject in a mugshot.”

Barnes and two assistants brought in reams of black cloth. Together they draped the fabric around the room, erasing the warehouse backdrop and isolating the subject completely. The shots required considerable technical skill, but once Barnes had a vision, it was simply a matter of execution. The final effect was striking.

In the photos, shot in black and white, the cabin is utterly decontextualized, a disembodied specter that seems frozen in time like a snapshot of Dorothy’s cabin hurtling away from Kansas. The cabin hovers halfway between fairytale and horror movie, a distorted icon of the American dream. The roof panels, perfectly rectangular, could almost be gingerbread, their edges dotted with precisely placed steel gumdrops. A single open window sits high above the ground, framing an impenetrable darkness within. The plywood walls, by contrast, glow ominously, bolts and imperfections in the wood limned in eerie, sterile white. Captured in this light—completely detached from reality, a sinister yet mundane object floating in a deep, dark nothingness—the cabin recalls the words of scholar and Freudian psychoanalyst Joel Kovel who described the schizophrenic experience as a “radical estrangement” from society and “a fortified island in a sea of emptiness.” Had the case come to trial, Barnes’s photos might have proved useful in the lawyers’ insanity defense.

“This building, in a certain way, so represented who he was,” Barnes says. But it was larger than that; in the cabin, Barnes also saw “this kind of crazy notion that we as Americans have about self-reliance and rural sanctity … and how incredibly malignant it was in relation to Kaczynski.”

Kriss was stunned by Barnes’s images. In them she saw the tension between appearances and reality, that “out of something so ordinary could come something extraordinary.” The color photo, in particular, would practically become magazine lore, she says. “It was one of the most powerful psychological images that I’ve ever seen.”

When magazines hit mailboxes, BARNES’S photos captured readers’ imaginations. Several wrote to the Times to share their reactions. One saw in the cabin’s image a longing for a simpler life, or “the ghost of our pioneer spirit.” Others praised the shot for its artistic merit. Someone imagined finding the piece at the MOMA: “Imagine the rave reviews. The rare simplicity! The beautiful stark lines! Why, it could be Thoreau’s!” Another wrote: “The photograph of Kaczynski’s home fooled me into believing that I was looking at a sculpture or an installation by a minimalist artist displayed in a glorious gallery,” adding, “As soon as I realized that it was the cabin of the Unabomber, chills ran down my spine.”

Barnes was gratified by the response.

“That’s exactly the reaction that I was looking for,” he says. Having approached the cabin first as a forensic artifact then as sculpture, he had, in a sense, reversed the experience for the viewer. “I wanted you to take that first meaning—this is an art object, is a piece of sculpture—and then realize what it really was in the world.”

Taken out of context, the photos are visually striking, but ultimately what gives them their power is Kaczynski and “the evil that he represents,” according to Oleson. “When I look at the images, they have the kind of taboo nature of participating, however vicariously, in something transgressive or dangerous,” Oleson says.

That deeply human desire to lean in closer and inspect the objects of evil has driven an entire industry of “murderabilia.” In 2018, the Guggenheim Museum in New York included Kaczynski’s typewriter in a show titled Take My Breath Away. A decade earlier, the cabin was featured in a 2008 exhibit at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., alongside other such artifacts as Patty Hearst’s bank heist coat and the electric chair used to execute the Lindbergh kidnapper. The exhibit saw nearly 400,000 visitors in the first six months.

Other artists, too, have created work based on Kaczynski’s home and belongings, including Daniel Joseph Martinez’s brightly painted, full-scale replica of the cabin, called The House America Built, and filmmaker James Benning’s reconstructions of both Kaczynski’s and Thoreau’s cabins. Writer Joy Williams gave voice to the cabin itself in her essay “Cabin Cabin.” And the list goes on.

While the cabin itself now sits in the FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., Barnes’s photos are housed in the collections of major museums throughout the country, including the Museum of Modern Art, SFMOMA, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Barnes is quick to acknowledge the irony—and the potential danger—of elevating such an object to the halls of fine art.

“[Some people] said, ‘Why are we giving this object of such horrific potential—what happened there, making the bombs—why are we celebrating this?’ And I understand that. I totally get that.”

He recalls a visit from a friend who, upon noticing a photo of the cabin in his living room, asked, horrified, “How can you have this around your children?” Barnes was sincerely surprised; he’d never seen the photos as something to hide from his family. To him, it’s a “symbol of our time.” And if seeing the cabin in that light creates some internal conflict or unease, well, of course it does. Art at its best, Barnes says, is transgressive and boundary-pushing and “can be uncomfortable.”

The root of that discomfort may stem, in large part, from our still-unresolved verdict on the Unabomber’s legacy. The possibility of any moral middle ground with respect to Kaczynski, the idea that he could have been both right and wrong in his crusade against technological society, gets to the heart of America’s contradictions—and Berkeley’s.

Long a hub of both anti-establishment thought and techno-utopian aspirations, Berkeley has been the birthplace of everything from 1960s counterculture and the Free Speech Movement to revolutions in artificial intelligence and genetic engineering. Almost four decades before the would-be Unabomber joined the university’s math department in 1967, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, got his start as an assistant physics professor. So yes, the roots of technocracy, and its criticism, run deep in Berkeley. (The very word technocracy was coined in 1919 by William Henry Smyth, an English-born engineer whose Berkeley residence, the Smyth House, was remodeled for him by 1894 alumna Julia Morgan.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the constellation of Berkeley connections to the Unabomber is vast and spans the ideological divide. Former Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephen P. Freccero, J.D. ’87, who served on the federal UNABOM prosecution team, is a Berkeley Law alum, as is famous civil rights attorney Tony Serra, J.D. ’61, whom Kaczynski lobbied to replace his own defense team. (In a 1998 article for the New Yorker, writer William Finnegan described Serra as a “True Believer” of the Kaczynski doctrine. “Indeed, [Serra] told a reporter, ‘This guy is a genius. He sees things we can’t see and understands things we can’t understand. Maybe we should give him the benefit of the doubt.’”)

Oleson points to Berkeley’s proximity to both Silicon Valley and San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. “Those two worlds sit so geographically close in tension, and Berkeley sits in the middle of them, both spatially and in terms of values,” he says.

Barnes, too, observed these resonances with his alma mater. “I found out that [Kaczynski] taught at Berkeley, and I’d gone to Berkeley, and I thought, ‘Well, that makes perfect sense,’” he says, laughing. “The reason I ended up at Berkeley was because I was curious about these issues around dissent and free speech and all the other things that Berkeley represents.”

All of these ironies and messy contradictions are alive in Barnes’s work. As Joan Didion ’56 famously wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live…. We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five.” So, what story does the cabin tell? Barnes’s photos remind us that a satisfying conclusion may not exist.

Or maybe he simply missed his chance to write the ending.

Five years after the original shoot, Barnes was called back to the warehouse for a major media event: The cabin was to be demolished. Only, at the last minute, Turtle pulled the plug. The cabin had been spared.

As the lawyers and journalists began to clear out, Barnes had an idea.

“My assistant and I are standing there, and I said, ‘You know, as an artist, to push the envelope, what I really need to do here is I need to burn the cabin down,’” he recalls. “I would have been arrested on the spot for all kinds of reasons. But I thought if I was a true artist, this is what I would have done.”

It’s Barnes’s deepest regret that he didn’t seize the opportunity to, in his words, “eliminate [the cabin] from the cultural dialogue.”

“I think in some ways it was the right thing to do,” he says. “It would have gone up in flames, and that would have been the end of it.”

Leah Worthington is a Bay Area–based writer and host of California’s podcast, The Edge.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.