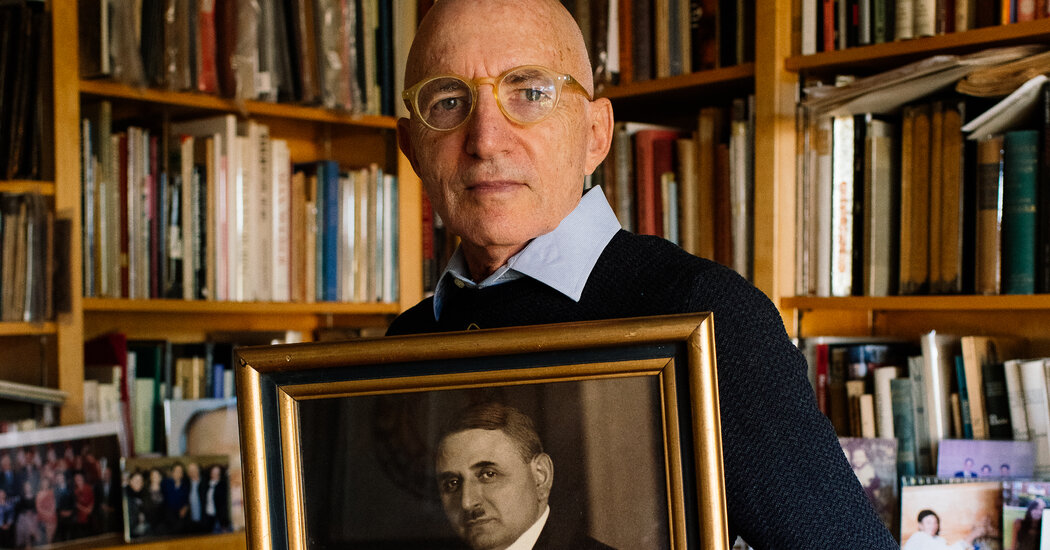

Despite limited success, Dr. Michael R. Hayden has spent more than a decade patiently searching for the looted silver Judaica stolen from his grandparents, who were killed by the Nazis.

His day began at 6 a.m. with a call to Amsterdam from his office in Vancouver. An hour later he gave an online lecture to a class in Ireland, immediately followed by a call with a scientist in Boston about research.

Dr. Michael R. Hayden is one of the world’s leading geneticists, the recipient of many of medicine’s highest awards and the founder of five biotechnology companies who, at 71, still teaches at the University of British Columbia.

To spend a day with him this month was to witness a whirlwind of endless activity. And yet Hayden also sets aside four to five hours each week to focus on a pursuit as important to him as his pioneering discoveries in neurodegeneration: finding the silver Judaica his family lost to the Nazis during the horrors of World War II.

“My life is so complex,” he said in an interview, “but this is priority for me and for future generations. I will always find time for this important endeavor. I need to be a living witness for what happened.”

Hayden knows well the account of how, on Nov. 10, 1938, the night of Kristallnacht, Nazi SS men broke into the home of his grandfather, Max Raphael Hahn, a wealthy businessman and chairman of the synagogue in Göttingen, a city in central Germany.

They arrested him and his wife, Gertrud.

She was released from prison the next day. But Max Hahn was imprisoned for seven months and his important collection of silver Judaica, with items dating back to the 17th century, was confiscated. Included were ceremonial lamps, candlesticks, kiddush cups and spice boxes.

Hayden has been able to recover dozens of other household items, and a few religious artifacts, which were held by a German museum. But the collection of silver Judaica that was seized by the Nazis has eluded him. Twenty years after beginning his project, and despite the support of a German organization that helped finance two years of research, he has only collected one of the 166 missing items, a kiddush cup.

Still, the Hayden effort is representative of the kind of dedication that many Jewish families have put toward recapturing art and other items confiscated from their relatives, or sold by them under duress during the Nazi era. Such work is often fueled by a sense of justice and a commitment to family, and, in the case of art, the loss of possibly substantial inheritances.

In the case of Judaica, the items can also be valuable. But the pursuit of them is often sustained by their legacy as religious heirlooms that speak to the faith for which relatives were persecuted and killed.

“The objects are important, not in terms of their value, but in terms of their significance,” Hayden said. “For me, it’s a step forward toward trying to close what is a deep and painful wound that stays with me every day. And trying to move forward to a new reality, of new relations, new acknowledgments, and some peace.”

Hayden is considered an expert on Huntington’s disease and A.L.S. (Lou Gehrig’s disease). He was born in South Africa, where he went to medical school and received a doctorate in genetics. He also completed studies in internal medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Today, he is chief executive officer of Prilenia, which focuses on clinical treatment for neurodegenerative diseases, and he is on the board of 89bio, which is developing new treatment for liver and lipid diseases. He has offices in Herzliya, outside Tel Aviv, and Naarden, near Amsterdam.

But he spends most of his time in Vancouver, where his office is filled with photographs of his four children, five grandchildren, books on Jewish history, and a photograph of Pope Francis blessing him.

Hayden’s search for his family’s heritage began in 1986 in the basement of the Göttingen City Museum. A curator allowed him to explore and he found a wimpel, a long thin cloth usually used as a Torah binder, with a family connection. It had wrapped his great-grandfather, Raphael Hahn, during his circumcision.

“There was no documentation and no information as to how the piece of cloth with my great-grandfather’s name sewn into it had arrived at the museum and who the donor was,” Hayden said.

“The Göttingen city council refused to return the wimpel unless I could find a replacement,” he continued. “The council said it would swap it if the mayor could find another one.”

Hayden contacted Artur Levi, Göttingen’s mayor, who was Jewish. Levi offered to help. Three months later, in February 1987, just eight hours before the birth of Hayden’s third daughter, a package arrived from Levi.

“In honor of her great-grandfather, Max Raphael Hahn, and great-great-grandfather, Raphael Hahn, she was named Jessica Raphaela Hahn and was wrapped in the wimpel two weeks later at her baby-naming ceremony,” Hayden said.

“My wife, Sandy, and I have five grandchildren,” he said, “and it’s the tradition to wrap each child in it at their birth, be it a boy or girl.”

Hayden’s search for his grandfather’s Judaica collection began in earnest decades later in his grandfather’s boxes: 15 cartons containing thousands of documents, vintage stamps and photographs, even the autographs of Mark Twain and President William McKinley. The boxes had been unopened for 20 years in a storage room of his Vancouver home.

“One night, I felt I should confront it,” Hayden said. “The letters tell incredible stories of heartbreak.”

After his grandfather, Max Hahn, had been released from prison, Hayden said, Hahn and his wife went to Hamburg, hoping to emigrate. But in 194l they were deported to Riga, Latvia, and put on a train destined for a concentration camp. Gertrud Hahn is believed to have died on the train. Max was killed in a mass shooting near Riga in 1942. The Hahns’s two children, Hanni and Rudolf, Hayden’s father, had been sent to safety in England in 1939.

Before he was sent to his death, Max Hahn in 1940 and 194l was able to ship many household items, including documents, letters, photos and family papers, to Sweden. Hand luggage with personal items was sent to Switzerland.

After the war, the Hahns’s children collected the containers and brought them to South Africa where Rudolf, who had changed his name to Roger Hayden, lived. He died in 1984.

These days, as Hayden works to research the whereabouts of the missing Judaica, he has the help of assistants. Sharon Meen, a historian, has worked with him for 13 years, helping to pore through auction and dealer catalogs and peruse museum collections.

“The boxes that went to Sweden and Switzerland contain an inventory of all the items in the Hahn Judaica collection, including dimensions and weight,” Meen said. “There are also many photos.”

Occasionally there are moments that make all the effort worthwhile. A few years ago, while checking the collection of the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Hamburg, Germany, Hayden found a photograph of a kiddush cup. It depicted scenes from the biblical story of Jacob, just as his grandfather’s cup had.

“I contacted the museum and they returned the cup to me,” he said.

Officials in Göttingen were also helpful in 2014 and 2015, when the city returned some 30 items once owned by the Hahn family, but most of which had been sold by Max Hahn under duress in 1938, Meen said. Some of the items, like a Rococo-era living room set, were featured in photographs that Hayden’s grandfather had left in the boxes. Most were household items, not religious artifacts. Still, the return of the items, whose connection to the Hahn family had been tracked by Meen using museum records, helped to illustrate the lives of people whom the Nazis had tried to erase.

Hayden, his wife and four children, and Max Hahn’s nine great-grandchildren flew to Göttingen from Brussels, London, Cape Town, Vancouver, Toronto, Los Angeles, Tel Aviv and New York to attend a 2014 ceremony to mark the return. They were also the subject of an exhibition at the museum, and Hayden decided to leave the items there on loan.

The silver Judaica has been more difficult to locate. Meen said she is convinced much of it is still in Germany but she has visited roughly a dozen museums without success.

“The search is not done,” Hayden said. “We continue only to make sure, not necessarily to have items in our own possession, but rather to have them attributed appropriately to my grandfather.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.