“Prisoners are like men and women who quit the human race,” said Chester Himes, former prisoner, detective novelist and blackballed screenwriter from the mid-20th century. Himes was Black when being Black wasn’t good.

Which brings me to “States of Incarceration,” the interactive traveling exhibit at UWM’s Student Union. The exhibit allows viewers to experience a criminal legal system simulation. Created by over 800 people in 18 states, “States of Incarceration” explores the roots of mass incarceration starting in colonial times. The roots sprouted weeds, and the weeds kept growing. The exhibit’s story angle is that the carceral system is built on fear and separation rather than effectiveness and reason.

Shannon Ross is the CEO of The Community, whose mission is to foster the full potential of people with criminal records through pre-entry. Ross and his staff are responsible for bringing the exhibit to Milwaukee. He knows a great deal about incarceration. When he was 19, Ross committed a violent crime and received a 17-year prison sentence. In 2014, while still incarcerated, he founded his organization, The Community, and created a newsletter read by 5,000 incarcerated people in the Wisconsin prison system.

I’ve known Ross since his release in 2020 and seen his activism for prison reform gain momentum. A few days ago, we met at the exhibit.

The States of Incarceration exhibit promises participants to navigate re-entry through a series of interactive activities. You spent 20 years in prison. What does it feel like to re-enter society after incarceration?

Coming home is different for everybody based on two things, one, on the level of support, and two, mental and emotional infrastructure. For me, I felt excited, felt right, but I wasn’t scared. In prison, I had kept up on the news and pop culture, and I read a lot. For many people, being released can be scary because they had spent their time being comfortable in prison. They wore the prison clothes, ate the prison food, used the prison laundry. They were living off whatever the state provides. Living on the outside can be a huge adjustment.

The number of people on parole and on probation in Wisconsin is three times the size of the state’s present prison population. Many of these people equate post-prison supervision, namely parole and probation, as similar to incarceration. How many people currently are on reentry?

|

|

Remember that probation is different than parole. Probation can mean you never went to jail but had a sentence of probation. But I’d say that 60 to 70% of those people are on parole from incarceration—40,000 to 50,000 are on parole.

I find it startling that people released from prison are kind of still in prison when they are on parole, but the walls are way wider.

Well said, yes, I agree.

Should there actually be a parole system or should parole be eliminated altogether?

I believe parole should exist because people who have been incarcerated need guidelines to reenter society. I have 15 years of parole and have 10 and a half years left. That is a complete waste because I have shown they can let me go. Generally, most states believe five years is enough parole because that time period will show if a person is stable. But in Wisconsin, the average parole time is eight to 10 years.

That just means more unnecessary taxpayer dollars go into the parole system.

The cost to keep each person on parole is about $3,000 per year.

Wisconsin has a unique set of laws and administrative codes governing the Department of Corrections (DOC). How do these laws and codes affect the lives of incarcerated individuals?

You mean the 303 codes, the prison rules. In Wisconsin, the worst rule is that if you are on parole, you can be revoked. I could be in my 15th year of parole, I get into a fight, and I win, and then the guy I beat up says I had drugs and a gun on me. While the investigation is ongoing, I am locked up in jail. A person should not be put back in jail for an allegation or during an investigation. There is a good chance I’d have to start my parole all over again, another 15 years.

Let’s talk about the public attitude toward released prisoners. I think there is a negative public perception problem, namely the public too often judges released prisoners as re-offenders who sell drugs, rob, rape or even murder.

You are absolutely right. The word, “criminal” already connotes negativity. That all comes from media, news, or family anecdotes. The news will highlight the word “ex-con” or “former inmate” if someone is even accused of something. At The Community, we try to highlight people who had spent time in prison as doing well back in society, but you rarely hear about that. Instead, the media covers the people who do badly.

Since 2000, Wisconsin’s recidivism rate for all offenders has been between 40% and 50%. The recidivism rate for violent offenders is higher than for non-violent offenders. Can rehabilitation programs in prison lower those numbers?

Those rehabilitation programs generally work if people who have previously been in prison are the teachers, and they talk to people who are still inside. They have to guide the programs or lead the programs. In California, there is a powerful program where former lifers go into prisons and teach classes. It works because the former lifer can teach how to navigate life on the outside.

Walking through the Exhibit

Conceived and constructed by Rutgers University-Newark, the “States of Incarceration” exhibit covers two large rooms, a series of display boards filled with prison history, photos, illustrations and explanations. A patron can use earphones to access a guided tour. The exhibit is broken down through stories of 18 states and goes back to colonial times, then moves forward to contemporary times. The displays emphasize victimization, prisoners suffering at the hands of incompetent guards and administrators hired by careless legislators. As Ross and I walked through, we exchanged observations.

“Most of the stories and photographs seem to be about prisoners who have been abused or wronged,” I said. “Almost every story told about prisoners portrays them as victims of the prison system. There are not enough stories showing what the formerly incarcerated did successfully when released.”

“That is a very good point,” Ross said. “The work that we do with The Community organization is to show the positive sides of the formerly incarcerated. But this exhibit was created about ten years ago when there was a tendency to focus on the side of pity.”

“I get it,” I said, “but times have changed. It isn’t the 1920s anymore. There are thousands of people, organizations and government agencies who currently want to help people released from prison get back into society and be productive members.”

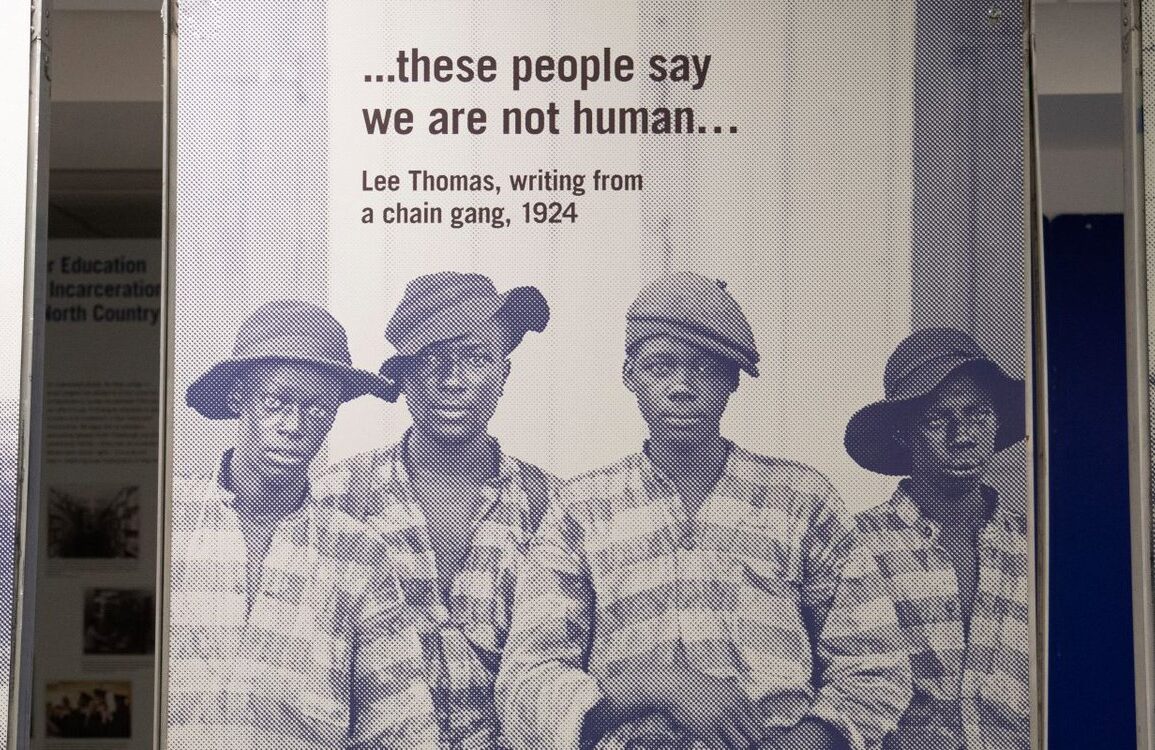

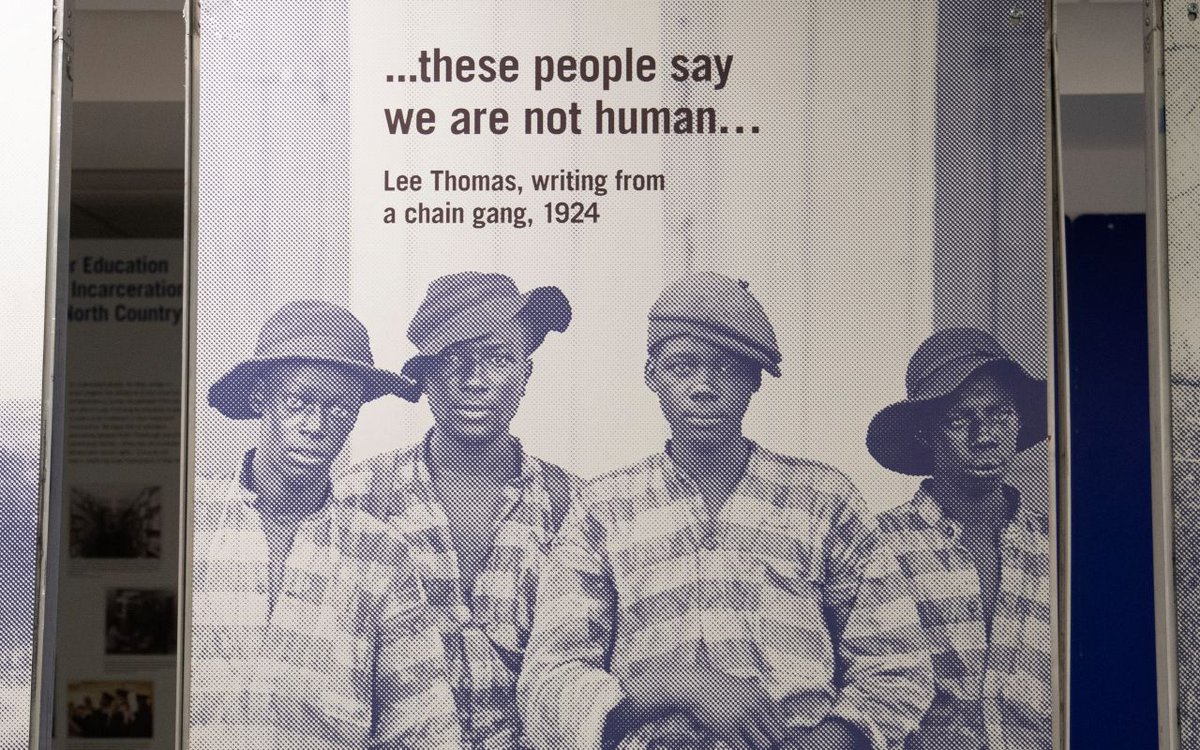

We paused in front of a huge photo of four Black chain gang members from 1924.

“This is history,” he said. “The exhibit tends to focus on different times in history and is broken down into different U.S. states and how prisoners were treated historically in each of those states.”

“Part of the exhibit also covers the incarceration or institutionalization of the mentally ill,” I said. “Sometime back in the 1960s, the beginning of the welfare era, state institutions that cared for the mentally ill were almost abolished, leaving care to family members or private care facilities. A lot of the homeless are mentally ill and can end up in jail where jail keepers are not equipped to handle them.”

“Yes, you are right,” Ross said. “Social workers and therapists should do that work. At one time in history, the prison, Dodge Correctional, in Waupun, used to be a facility for the mentally ill. My uncle actually worked there.”

We paused to look at two story boards dedicated to the death penalty. “Fortunately, we don’t have the death penalty in Wisconsin,” he said. As of January 2024, 24 US states have the death penalty, while 23 do not, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. In 2024, 10 states sentenced people to death, and nine states carried out executions.

We stopped at a display featuring this question: Who works for prisons and who do prisons work for? “This is an interesting question,” I said.

“Most prisons are located in rural or small-town areas,” Ross said. “That means the security and staff live in those areas, and they have difficulty relating to the majority of prisoners who are from urban communities like Milwaukee. Many are people of color. In prison, I learned that the only difference between the incarcerated and prison staff members is we got caught. I’ve even heard staff members say that. I’m referring to citizens who had been drinking and driving or on drugs or some who have committed domestic violence, and they got away with it.”

“So who do the prisons work for?” I asked.

“The prisons work for the people that monetarily profit off prisons,” he said. “Many businesses invest in prisons through contracts and care. But society does benefit from people coming home, and certain incarcerated people should be there. But should people be in prison for failing to pay child support or for drug use or mild theft? However, I will say there are judges and prosecutors who are trying to keep people out of the system.”

We paused in front of another exhibit board raising the question of how is the racialized prisoner the ideal worker? Is it because of free or cheap labor?

“Yes, that is the point,” Ross said. “Some prisoners do industry work. A significant amount of furniture in the Wisconsin universities come from prisoners making that furniture. I believe that is a state requirement. At one time, Louisiana’s Angola Prison forced prisoners to work for free on farms and in fields.”

We moved on. “What can we learn from listening?” I said.

“If you are listening to people who have experienced the prison system and have come home, and are talking about their transitioning back into society,” he said, “then that is worthwhile. Think about it. Residents are paying a lot of money to house prisoners, and they probably want to know they will reform. There is also restorative justice where victims work out a compromise with the perpetrator, who avoids prison time and saves taxpayer money. That can be a solution in certain situations. The formerly incarcerated are much like ordinary citizens. They don’t want crime or criminals in their neighborhoods.”

We stopped to discuss a racial issue featured on a display board. “This is kind of like the Jim Crowe era of laws,” I said, “Blacks being treated with prejudice even as prisoners.”

“It’s easy to say, ‘well, these are the laws, do not break them,’” Ross said. “But if we have laws that are designed for a specific demographic like economic classes and minority races, then you have Jim Crowe evidence.”

We finished our tour in front of two walls. Adhered to the walls at right angles were numerous flag-like cards which follow a timeline from 1851 to 2015, each card illustrating what happened during to laws and punishments in the year represented.

“Over those years, laws have changed,” I said, “for instance, drug laws, once illegal, now legal, such as consumption of marijuana.”

“Black and brown people, especially, went to prison over minor drug charges,” Ross said. “And now corporate cannabis growers are making a lot of money legally.”

The States of Incarceration Exhibit can be seen through Friday, March 14 at the UWM Student Union East, 2nd floor across from the bookstore.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.