These 42 mostly black and white works, the original “thug life” drawings, have a lovable but menacing charm—a deep wrongness that somehow looks right. They survive because in the 1940s, Joseph Cyrus Massey, an incarcerated African-American man, sent mail embellished with sketches and stamped CENSORED, to the ultimate aesthete, Charles Henri Ford, on East 53rd Street in Manhattan for the trailblazing Surrealist magazine, View.

The scenarios are normal enough: people interact with each other and with animals. A dog looks at a woman’s thigh, perhaps about to bite. A couple hugs as two individuals watch. Three people are stacked like acrobats, their mouths open. In one work, a woman seems to be tumbling onto a dog.

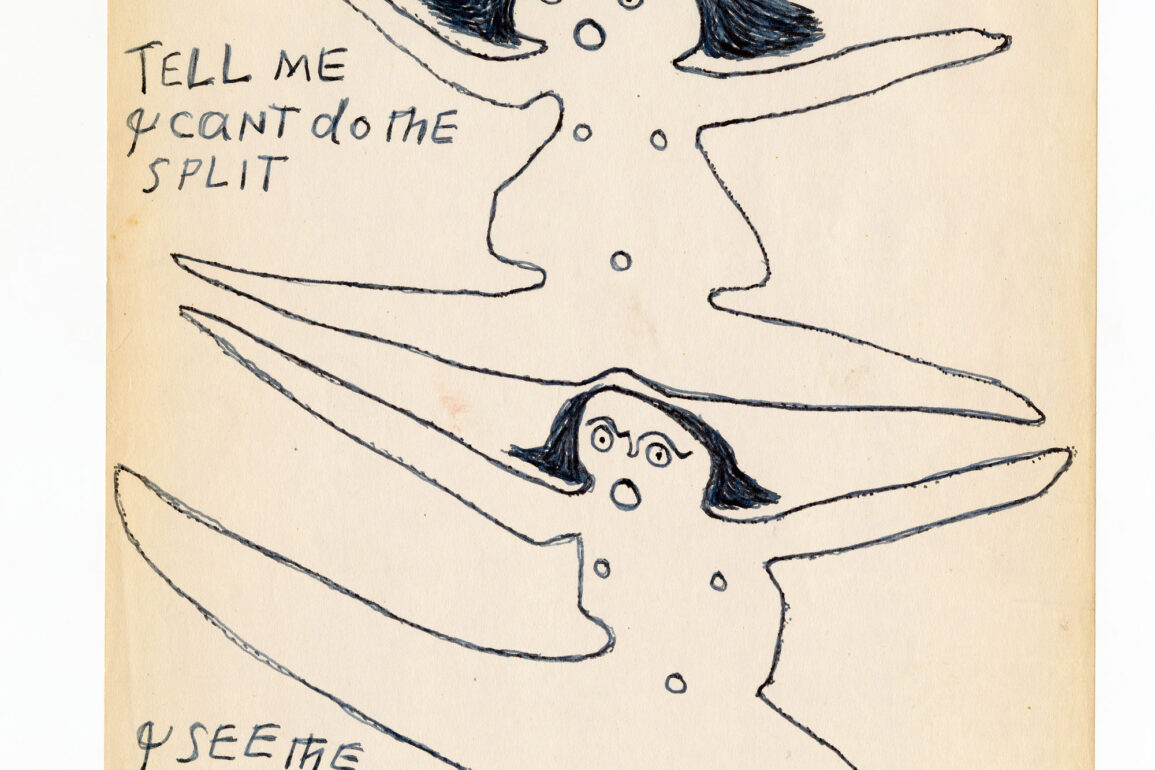

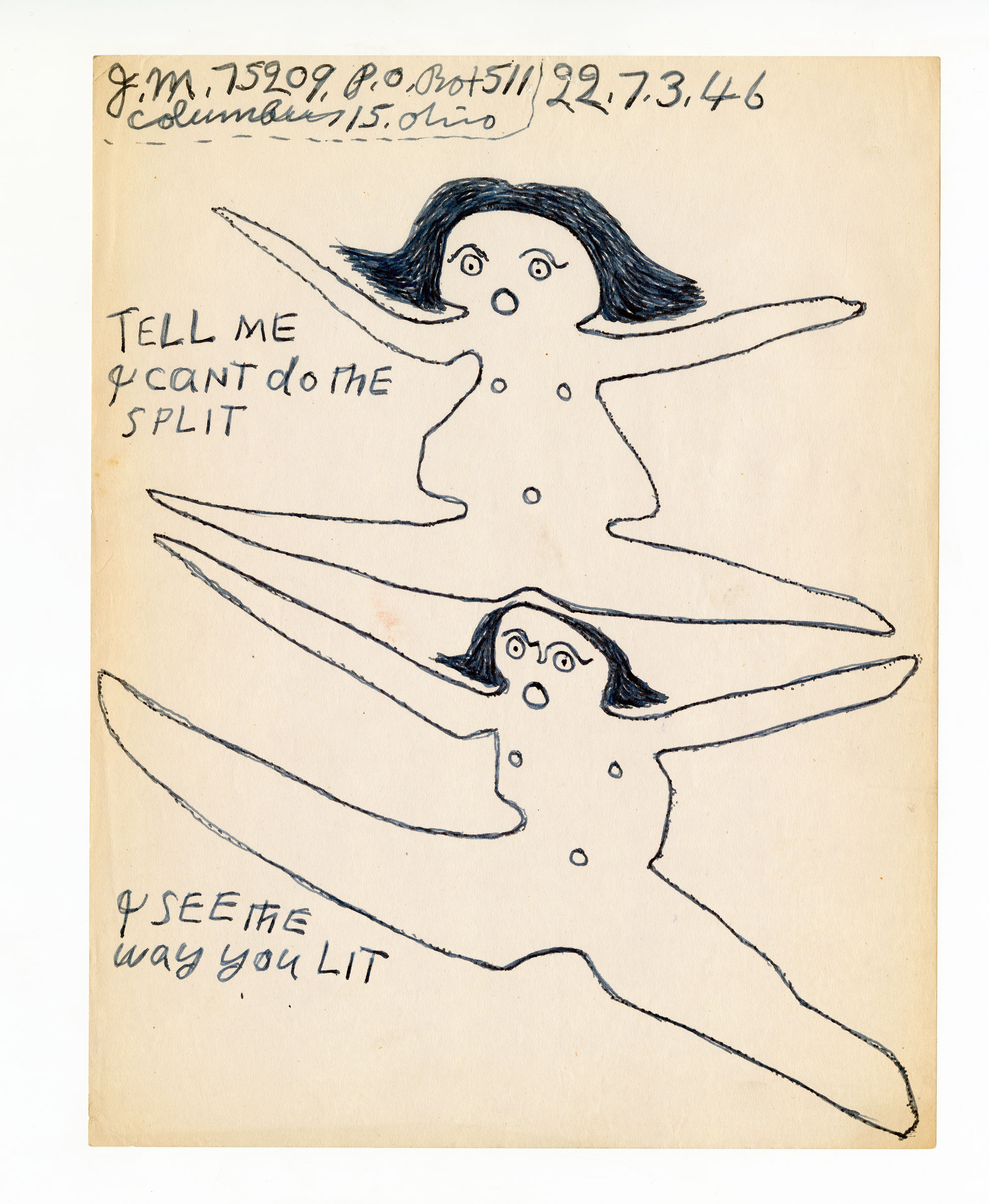

But closer looks reveal an unapologetically strange world: surrounding the falling woman Massey wrote, “Sit down. And dont get hurt. I Told you. Not to flurt” [sic]. Some figures sport wing-like crescents or don’t have arms. When they do, gesturing hands resemble combs or “sporks” without thumbs. In at least one example, naked feet do have thumb-like extensions. Most feet are boot-covered—lumbering, exaggerated maps of Italy. A skirt is shaped like a tree trunk. Pockets, collars and parts of bathing suits and dresses are obsessively colored in, compulsively jet-black, making freakish fashion statements.

Characters float in peculiar landscapes: mega-human forms on display, fused into conjoined twins or multi-armed anthropomorphic snowflake-beings. Hard-edged shapes like early Beatles haircuts or “Uncle Fester” domes project sexual ambiguity. Sine-wave eyebrows divide heads in half, like bathing caps. Noses are single vertical lines or basic V- or M-forms descending from bangs. Mouths and eyes are simple circles, the former agape, the latter with dots added, somehow expressing instant emotion from alarm to delight. In profile, human noses and mouths become beaks, or mountain peaks, oddly paralleling animal faces. In one quarter of the images, suns preside over the action from the upper right, sporting mandala eyes and smiles, smirks or sneers, revealing their opinions of the scenarios below.

Some of Massey’s four-legged creatures and humanoid colleagues predict Keith Haring gingerbread-man silhouettes, but feel more enigmatic, intriguing and disturbing. Haring-esque dog-profiles also enter the scenes from the sides, featuring cut-off neck down and wielding other-worldly snouts, always made up of two bizarre, screwball shapes facing each other: crosses between toothbrushes and “Wimpy” moustaches from Popeye cartoons. In one work, horses float above a river, half-animal, with Native American-like paw and leg tributaries protruding. Elsewhere sharks, camels or buffalo that have eaten humans whole appear in profile, hovering triumphantly, prey visible within.

Children’s art, the creations of the mentally ill, outsider art by visionaries, and so-called “savages” of indigenous cultures were considered sacred for the Surrealists, as were automatic writing and dreams, after Freud explained their potential to transcend an oppressive “reign of logic” over instincts, making the impossible achievable, the fantastic feasible and offering liberation from the shackles of etiquette and reason. Thus, when Charles Henri Ford, who introduced the avant-garde to U.S. audiences through View, discovered the autonomous cartoon art of Joe Massey, killer of two women, they must have enraptured him as vehicles to his own reformation—and America’s. “I have made a mistake in my life and I am trying to make the best of it,” Massey wrote him. “[…] to overcome my past mistakes. And to rehabilitate myself. […]I am waiting for a better day.”

So Ford published the work, sending back issues of View, checks, and art paper. Massey drew in blue-black ink, probably with a dip pen, with almost every line carefully drawn twice, giving these portrayals their idiosyncratic appeal. But, in addition to showing some very likable art, Ricco Maresca has also put front and center some questions that might sting: Is it OK to revel in a murderer’s art? Is it patronizing to appreciate outsider art for a perceived lack of “skill?”

Let us acknowledge what we know of the artist. Joe Massey was born in 1895. When trying to kill his wife, he accidentally killed the wrong woman in Little Rock, Arkansas. He was sentenced to ten years, but served only one by escaping and living as a fugitive for two decades. Next he shot and killed his second wife, escaping the electric chair but sentenced to life in prison in Columbus, where these drawings originated. His entry in the Ohio Penitentiary Register of Prisoners says he was admitted in 1939 for sixteen years with the last 5 in nearby Marion Corrections Institution. He was paroled in 1959, and released in 1965. In 1961 New York’s Greenwich Book Publishers published Singing Stars, a book of his poems. A copy survives in the New York Public Library.

Massey signed every work in the upper left corner with his initials, prisoner number (inmate no. 75209), and a Columbus P.O. Box, acutely aware of who and where he was. After his release, no trace of him remained. The visual evidence from his previous life is all that’s left.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.