Abstract

The footprint of the legal system in the United States is expansive. Applying psychological and neuroscience research to understand or predict individual criminal behavior is problematic. Nonetheless, psychology and neuroscience can contribute substantially to the betterment of the criminal legal system and the outcomes it produces. We argue that scientific findings should be applied to the legal system through systemwide policy changes. Specifically, we discuss how science can shape policies around pollution in prisons, the use of solitary confinement, and the law’s conceptualization of insanity. Policies informed by psychology and neuroscience have the potential to affect meaningful—and much-needed—legal change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On any given day there are more than 1.9 million people behind bars in jails or prisons in the United States1. Nearly half of all adults living in the United States experience incarceration in their family2. Most who encounter the criminal legal system are dealing with problems related to poverty and mental illness, which worsen with arrest and incarceration2,3,4,5.

With the hope of trying to shrink the footprint of the criminal legal system on American families, over the past two decades, much discussion has focused on the applicability of psychology and neuroscience to the legal system. These discussions are rife with conjecture around the notion that psychology and neuroscience can detect liars, objectively determine criminal responsibility, and predict who will engage in violent behavior. Unfortunately, the framing of psychology and neuroscience as being able to transform the law by focusing on the individual reflects a misrepresentation of the science and the standards of law.

Psychology and neuroscience provide probabilistic, not deterministic, estimates of phenomena in the aggregate. While psychological and neuroscientific findings may be valid for a given group in general, they may not apply to a particular individual within that group (often referred to as the group-to-individual problem). Thus, psychological and neuroscientific techniques cannot show beyond a reasonable doubt that distinct brain structures or abnormalities affect the mental state of a particular individual at the time of the crime, that they will undoubtedly engage in criminal conduct in the future, or evidence of mitigation at the sentencing phase above and beyond other less expensive and more reliable tools (e.g., assessing family history or exposure to violence).

While there is much skepticism about the use of psychology and neuroscience in the legal system, these disciplines do have the potential to affect meaningful change in how the legal system operates and in the outcomes it produces. In this perspective piece, we will argue that psychological and neuroscientific findings can be applied to and improve aspects of the legal system through policy changes. We will focus on how science can shape policies that affect those who are incarcerated in jails and prisons, and by extension society at large. There is a substantial body of research delineating the negative impact of incarceration on individuals (e.g., negative effects on health, mental health, job prospects, educational attainment, etc.)6,7,8,9 and their families2,10. Here, we select three aspects of where and who is incarcerated and detail how policies surrounding these aspects can or should be influenced by emerging findings in psychology and neuroscience. Specifically, we highlight how the issues of pollution in prisons, the use of solitary confinement, and the restrictions of the legal concept of insanity could be reshaped by integrating scientific findings.

Criminal legal system aspects of interest

Pollution: toxins and noise

The United States continues to incarcerate more people than any other country. Over 6000 facilities hold almost 2 million people. The long reach of incarceration substantially reduces the chances of a formerly incarcerated person obtaining an education, stable employment, owning a home, or living above the poverty line5. Further, exposure to toxins and noise pollution within jails and prisons in the United States will likely have substantial negative effects on the individual’s psychological and brain health.

There are documented violations, ranging from inadequate sewage and waste disposal to poor water quality and the presence of toxins such as asbestos, manganese, and lead, in jails and prisons throughout the United States11,12,13,14,15,16. For example, since 2000, over a quarter of California’s state prisons have been cited for major water pollution problems13. Rikers Island, a jail in New York City, was built atop a toxic landfill in 193217,18 that in 2011 the New York City Department of Correction reported was still emitting poisonous gases19. Since 2020, at least 23 jails have been either proposed or constructed on toxic and contaminated lands16. Further, regulations that would protect the general population against toxin exposure often are not in place for jails and prisons (e.g., the Environmental Protection Agency designated that most parts of prisons and juvenile detention centers are zero-bedroom dwellings [i.e., residential dwellings where living areas are combined with sleeping areas] and therefore are not subject to the Lead Renovation, Repair and Painting Rule)20. Exposure to such toxins causes health problems, including cancer, hypertension, and neurodegeneration, as well as mental health problems, including impulsivity and aggression21,22.

Similarly, noise pollution is an issue in jails and prisons23. Sources of noise in prisons are unpredictable and come from multiple streams. These facilities often are built using hard, reflective materials that heighten noise pollution. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency defines acceptable levels of noise in residential areas, hospitals, and schools as 45 dB(A)24. However, the American Correctional Association set noise standards for correctional housing to not exceed 70 dB(A)25. Long-term exposure to sound above 50 dB(A) has been shown to cause serious health issues, such as increases in stress hormones, cardiac problems, and hypertension26,27.

Research in psychology and neuroscience provides key findings that support the claim that exposure to toxins and noise in prisons can negatively impact physical and mental health. With regard to toxins, research in non-human animals and humans shows that exposure to chemicals such as lead, arsenic, and manganese cause serious harm. Specifically, documented harms include damage to dopaminergic neurons (which regulate motivation, reward, and habit learning28) and increase beta-amyloid protein plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (which characterize Alzheimer’s Disease)29. Additionally, exposure to such toxins result in deficits in the structure and function of the hippocampus (a region of the brain important for memory and learning30), increase neuroinflammation, and produce general poorer brain health31,32,33,34,35. Furthermore, high concentrations of neurotoxic chemicals and persistent pollutants have an undisputed impact on cognition and are associated with deficits in general cognitive functioning, IQ, executive functioning, language, and memory21,22,36,37. Of utmost relevance for the legal system, toxin exposure in the short-to-mid-term is linked to heightened levels of impulsivity, hyperactivity, and aggressive behaviors11,38,39,40,41.

Noise pollution and chronic noise exposure also have long been considered an ecological stressors that impact psychological and neural functioning. Prolonged noise exposure causes clinically impairing distress and stress hormone dysregulation27. Studies with non-human animals and humans link chronic noise exposure, particularly unpredictable noise, to damage to the central nervous system, the generation of pathological neurofibrillary tangles (which is related to Alzheimer’s disease), and poorer tissue health in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex (a region related to self-control), and amygdala (a region important for emotion processing and regulation)42,43,44,45,46. These neural alterations appear to persist even after noise exposure stops, suggesting both short- and long-term neurological impacts due to chronic noise exposure.

There are clear connections between pollution, toxin and noise, and physical and mental health problems. These pollutants have the potential to negatively impact neural regions responsible for basic emotion, cognition, and behavioral control. Using findings from psychology and neuroscience to understand the effects of toxin and noise pollution across species necessitates improvements in the ecology of jails and prisons.

A significant problem with current jail/prison environmental policies lies in the oversight of facilities and the enforcement, or lack thereof, of policies intended to ensure environmental safety. Frequently, jail and prison facilities are constructed in areas where significant ecological risk factors exist and require substantial remediation efforts to ensure safe occupancy, but these efforts either fail to materialize or are abandoned before completion15,47. The result has been exposure and vulnerability to serious health and safety risk factors like toxins or ecological disaster48. The failure to complete mandated remediation can be compounded by reduced access to legal remedies by incarcerated populations49.

To shrink the footprint of this aspect of incarceration, policymakers should prioritize two strategies. First, they should redouble their efforts to enforce existing laws and regulations that govern applicable environmental standards and ensure that remediation efforts are completed. Second, they should adopt a principle that no policy that limits movement, fraternization, occupational activities or contact with outside environments/persons should be issued without an evidence-based accounting of the harms associated with that policy, including strategies for addressing those harms50. With sufficient will and attention to these problems, there is reason to believe that conditions and outcomes within jails and prisons can be substantially improved.

Solitary confinement

Solitary confinement refers to the physical and social isolation of an individual in a cell for twenty-two to twenty-four hours a day. The cells typically are sparse, consisting of a steel door, a bed, a toilet, and a sink. Loud, unpredictable noise permeates the space that is no bigger than 6 feet x 9 feet51, and many cells lack natural light. People are in solitary confinement for periods that range from days to weeks, months, years, or even decades51. In 2021, approximately 48,000 individuals were held in solitary confinement51. Ten percent of people in solitary had been held for three years51. One may reasonably presume that the severity of solitary confinement would tend toward its sparing use, reserved only for the most egregious and dangerous offenders. However, the reality is that people can be placed in solitary confinement for various reasons, including for minor disciplinary infractions or for their safety52. The latter holds true for those deemed to be particularly vulnerable to victimization within incarcerated populations, including LGBTQIA persons, pregnant persons, and those with mental illness51. Although isolation for one’s protection can be voluntarily requested by an incarcerated person, jails and prisons can exercise their discretion to involuntarily isolate someone when officials determine that they cannot otherwise ensure that person’s safety, resulting in involuntary confinement that is largely indistinguishable from more punitively-motivated solitary confinement.

Research on solitary confinement includes qualitative accounts of incarcerated persons’ experiences and empirical studies examining the relationship between this aspect of incarceration and safety, mental health, and criminogenic risk. While the qualitative accounts, as well as popular media sources and theory-based writings from scholars, document the harrowing effects of solitary on individuals53,54, the empirical evidence supporting the negative effects of solitary on safety, mental health and criminogenic risk is more mixed. Some studies fail to detect effects of solitary confinement on individual behavior and mental health55,56,57,58. Other studies document significant negative effects of solitary on incarcerated people’s physical and mental health59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68, particularly in terms of anxiety, psychotic symptoms, sensory arousal, and behaviors that effect mortality by any or unnatural causes (e.g., suicide)57,64. Additionally, there is evidence that being housed in solitary confinement, even for a week, can change alpha frequencies measured by EEG57,69. The U.S. Department of Justice acknowledges that solitary confinement can worsen existing mental illnesses and trigger new ones70.

The study of solitary confinement is understandably very difficult. Some studies cited above lack appropriate methodological controls (e.g., randomization, comparison groups), were conducted in small samples, and/or were the result of litigation possibly introducing bias into the method71,72. Unequivocal empirical evidence for concluding that the practice of solitary confinement in jails and prisons is uniformly negative is lacking, leading some scholars55,57 to suggest caution in developing policy based on an incomplete science. However, there is a more substantial evidence base on the negative effects of solitary conditions in research with non-human animals and humans outside of the jail/prison context. While research in laboratories or in other institutional setting is not identical to incarceration-based solitary, there is a strong basis for comparing the effects of physical isolation and the deprivation of basic experiences.

Numerous studies with non-human animals explore what happens to the brain and behavior when subjects are physically isolated, deprived of resources, and are deprived of sensory information. These studies document trends including the expression of hyperactivity, altered responses to stressors, cognitive impairments, increased aggression, and alterations in mesolimbic dopamine functioning (which is important for learning and goal-directed behaviors)73,74,75. Rats in isolation also experienced lasting changes in psychological (e.g., aggression or fear of new situations), cognitive (e.g., declines in mental flexibility), and neural (e.g., reduced prefrontal cortex volume, decreased cortical and hippocampal synaptic plasticity, or alteration in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system) functioning as compared to rats in stimulating or complex environments76,77,78,79,80,81.

Similar patterns are found in some human studies, particularly those involving youth exposed to institutional settings characterized by deprivation of interpersonal contact. In one longitudinal and randomized study of children monitored through the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (https://www.bucharestearlyinterventionproject.org/about-beip), youth with histories of institutional residence had indicators of significantly worse brain health and atypicalities in neural structure, function, and communication compared to non-institutionalized youth82,83,84,85,86. Further, youth experiencing psychosocial deprivation display deficits in memory and executive functions compared to non-institutionalized youth87,88. The randomized design of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project provides some of the strongest causal evidence of the impact of isolation on development, with lasting effects.

Together, extant non-human and human research serve as evidence that psychological and neural differences are either generated or exacerbated by conditions of isolation. Solitary is not only painful in itself but also “undermines people’s sense of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningfulness … reduces pro-social behavior, and impairs self-regulation”89. Research across disciplines, then, provides a clear foundation that, on average, solitary confinement or similar conditions is physically and psychologically harmful.

In 2016, President Obama adopted a recommendation to end solitary confinement for juveniles in federal prisons. However, in 2023, 11 states still have no limits on the use of solitary confinement for juveniles, and just under half the states have passed laws that narrow the use of solitary confinement in juvenile facilities90. In 2023, the U.S. House of Representatives introduced a bill to ban solitary confinement in federal prisons91. To date, however, similar bills have not passed.

The footprint of solitary confinement, including deleterious psychological and neural effects (above and beyond just incarceration), has been argued in the courts to represent an Eighth Amendment violation that constitutes cruel and unusual punishment (see arguments from Ashker v. Brown)92,93. Solitary confinement should be used only for brief periods and as a very last resort. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners94— known as the Mandela Rules—condemn the use of solitary for people with mental and physical disabilities; such rules should be mandated in the United States across federal and state levels. They would serve to protect not only the incarcerated individual, but also the facility staff and society at large.

Redefining the legal concept of insanity

The U.S. legal system is continuously confronted with the need to adjudicate, assess, and treat people with mental illness95,96,97. How the law defines mental illness can have a substantial impact on how individuals who enter the system are judged and handled. For instance, in the United States, prevailing legal doctrines, including under the Model Penal Code, which has been adopted by 20 states, dictate that individuals may be considered less responsible if they can show that “at the time [their criminal conduct was] a result of mental disease or defect” indicating that the person “lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality [wrongfulness] of [their] conduct or to conform [their] conduct to the requirements of law”98,99,100, and therefore they can be found not guilty by reason of insanity. A successful determination of not guilty by reason of insanity can then trigger a therapeutic intervention via placement in a forensic mental health center (i.e., justice-involved treatment setting) over a punitive intervention via incarceration in a traditional prison.

However, the insanity defense is rarely used in practice because it is very difficult to demonstrate legal insanity101. Additionally, some legal policies greatly limit who even qualifies to present this defense. For example, the Model Penal Code’s insanity defense excludes disorders characterized by repeated criminal or antisocial conduct. Here, we argue that the disconnect between legal conceptualizations of insanity on one end and psychological and neuroscientific understandings on the other can lead to the inadequate acknowledgment of many mental health problems in the criminal process.

One of the difficulties in referring to insanity in legal proceedings is the disconnect between terms used in the law and how they would be considered in psychology/neuroscience. For example, legal policies related to insanity refer to “mental defect” or “defect of reason” as a premise for questioning criminal responsibility98. In the law, there is no clear definition of what is meant by these specific phrases. In psychology and neuroscience, we might operationalize these phrases as an aberration in cognition and emotion that undermine accurate perception, interpretation, and/or reaction to information. This operationalization provides a biopsychology basis for understanding an individual’s conduct102. As another example, “disease of the mind” is noted in some insanity doctrines98, again without a clear definition. In psychology and neuroscience, we might operationalize this phrase as brain-based pathology resulting from various causes (e.g., injury, genetics, environmental stress) and that is characterized by identifiable signs or symptoms. In this case, a biopsychological definition would specify the type of evidence needed to initiate a defense based on insanity. As a result of bridging the gap between the language of the law and science, individuals with disorders where psychological and neuroscientific evidence provides a clear basis for disruptions that undermine cognition, affect, and behavior should103,104, without question, be eligible to put an insanity defense. However, the lack of a clear, objective, evidence-informed legal standard for identifying insanity precludes this outcome.

A shift in the legal policy around insanity would provide a scientific-based basis for determining the groups of people who are eligible for such a defense. It is then up to courts to determine if there is clear evidence that the specific factors played a role in an individual’s behavior. At this time, though, the courts cannot properly make these determinations without the ability to conduct a frank assessment of any intersectionality between mental illness and criminality. Unfortunately, the prevailing legal standards around insanity preclude these very assessments based on ill-defined terminology and exclusion of certain disorders. By widening the potential eligibility for an insanity defense based on scientific evidence, many people currently ensnared in the legal system may qualify for special protections under the law and might need to be mandated to treatment. Further, psychological treatments that specifically target the neural basis of these cognitive and affective psychological differences already exist, such as cognitive training programs that target attentional/other cognitive biases, emotion regulation strategies, or behavioral treatments that target reward hypersensitivity103,105,106,107,108, providing an opportunity for rehabilitation. Broadening the scope of individuals who may be eligible for consideration under insanity doctrines could drastically reshape how mental illnesses are handled in the legal system, perhaps reducing the current footprint of a punitive system and shifting the focus to a system that more properly considers the role of mental health problems in some people’s behavior. If done correctly, this shift should feasibly improve safety outcomes, both individually and systemically, through deliberate intervention against underlying psychological motivators of behavior.

Outlook

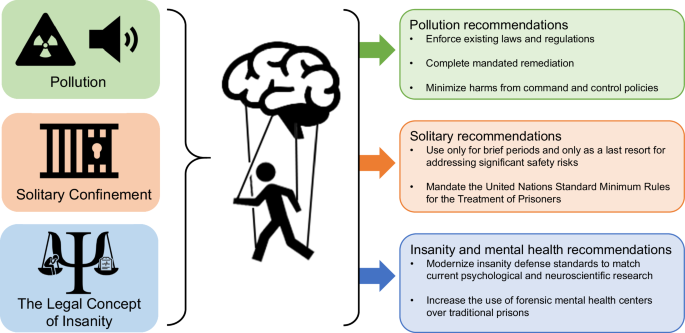

Psychological and neuroscientific findings are compelling as they apply to the impact of pollution and solitary confinement on behavior and the brain. Psychological and neuroscientific findings that challenge our understanding of ‘insanity’ raise questions about the handling of mental health problems in the current legal structures. Using research grounded in psychology and neuroscience in each of these aspects of the legal system overcomes some of the limitations outlined above with regard to the ecological fallacies and deterministic assumptions often made when applying evidence to the criminal legal system–instead of focusing on the individual, we can apply science to inform policy changes that affect groups of individuals (see Fig. 1 for summary).

In a landscape that often looks plagued by injustice, lacks an empirical evidence base, and imposes a tremendous cost on individuals and society both in terms of crime and punishment, it is imperative to look for alternative ways of integrating psychology and neuroscience findings and improving policies. If implemented appropriately, these robust psychological and neuroscientific findings have the tremendous potential to affect meaningful—and much-needed—legal change in the United States today.

References

-

Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. Prison Policy Initiative https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html (2023).

-

FWD.us. Every Second: The impact of the incarceration crisis on America’s families https://everysecond.fwd.us/ (2019).

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. About criminal and juvenile justice. https://www.samhsa.gov/criminal-juvenile-justice/about (2022).

-

Western, B. Incarceration, Inequality, and Imagining Alternatives. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 651, 302–306 (2014).

-

Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/ (2023).

-

Massoglia, M. & Pridemore, W. A. Incarceration and health. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41, 291–310 (2015).

-

Western, B., Braga, A. A., Davis, J. & Sirois, C. Stress and hardship after prison. Am. J. Sociol. 120, 1512–1547 (2015).

-

Harper, A. et al. Debt, incarceration, and re-entry: a scoping review. Am. J. Crim. Justice 46, 250–278 (2021).

-

Haney, C. Prison effects in the era of mass incarceration. Prison J. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885512448604 (2012).

-

Sundaresh, R. et al. Exposure to family member incarceration and adult well-being in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2111821–e2111821 (2021).

-

Gottschalk, L. A., Rebello, T., Buchsbaum, M. S., Tucker, H. G. & Hodges, E. L. Abnormalities in hair trace elements as indicators of aberrant behavior. Compr. Psychiatry 32, 229–237 (1991).

-

Toman, E. L. Something in the air: Toxic pollution in and around U.S. prisons. Punishm. Soc. 14624745221114826, https://doi.org/10.1177/14624745221114826.

-

Prison Ecology Project. Facts https://nationinside.org/campaign/prison-ecology-project/facts/ (2023).

-

Nigra, A. E. & Navas-Acien, A. Arsenic in US correctional facility drinking water, 2006-2011. Environ. Res. 188, 109768, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109768 (2020). People who were incarcerated in the Southwestern United States from 2006-2011 were at disproportionate risk of exposure to elevated drinking water arsenic (a potent carcinogen) and related disease.

-

Bernd, C., Mitra, M. N., Loftus-Farren, Z. & Truthout. America’s toxic prisons: the environmental injustices of mass incarceration, https://truthout.org/articles/america-s-toxic-prisons-the-environmental-injustices-of-mass-incarceration/ (2017).

-

Mahoney, A. & Truthout. Across the midwest, counties are building new jails on toxic land, https://truthout.org/articles/across-the-midwest-counties-are-building-new-jails-on-toxic-land/ (2022).

-

City of New York. History of DOC, https://www.nyc.gov/site/doc/about/history-doc.page.

-

Porter, E. S. Camera, Inc. T. A. Edison, Paper Print Collection, and Niver. Panorama of Riker’s Island, N.Y., https://www.loc.gov/item/00694387/ (1903).

-

New York City Department of Correction. Rikers Island Cogeneration Plant. (2011).

-

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Are prison facilities and juvenile detention centers built before 1978 considered target housing? https://www.epa.gov/lead/are-prison-facilities-and-juvenile-detention-centers-built-1978-considered-target-housing (2023).

-

Lanphear, B. P. The impact of toxins on the developing brain. Annu. Rev. Public Health 36, 211–230 (2015).

-

Liu, J. et al. Assessment of relationship on excess arsenic intake from drinking water and cognitive impairment in adults and elders in arsenicosis areas. International J. Hyg. Environ. Health 220, 424–430 (2017).

-

Wener, R. E. The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology (ed S. D. Clayton) 316–331 (Oxford University Press 2012).

-

Abatement, É.-U. O. o. N. & Control. Information on Levels of Environmental Noise Requisite to Protect Public Health and Welfare with an Adequate Margin of Safety. (Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Noise Abatement and Control., 1974).

-

Fairweather, L. & McConville, S. Prison Architecture. (Routledge, 2013).

-

Maschke, C., Harder, J., Ising, H., Hecht, K. & Thierfelder, W. Stress hormone changes in persons exposed to simulated night noise. Noise Health 5, 35 (2002).

-

Ising, H. & Kruppa, B. Health effects caused by noise: evidence in the literature from the past 25 years. Noise Health 6, 5 (2004).

-

Wise, R. A. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 483 (2004).

-

Sharma, S. et al. Effect of environmental toxicants on neuronal functions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 44906–44921 (2020).

-

Voss, J. L., Bridge, D. J., Cohen, N. J. & Walker, J. A. A closer look at the hippocampus and memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 577–588 (2017).

-

Landrigan, P. J. et al. Early environmental origins of neurodegenerative disease in later life. Environm. Health Perspect. 113, 1230–1233 (2005).

-

Jing, J. et al. Changes in the synaptic structure of hippocampal neurons and impairment of spatial memory in a rat model caused by chronic arsenite exposure. NeuroToxicology 33, 1230–1238 (2012).

-

Pandey, R. et al. From the cover: arsenic induces hippocampal neuronal apoptosis and cognitive impairments via an up-regulated BMP2/Smad-dependent reduced BDNF/TrkB signaling in rats. Toxicol. Sci. 159, 137–158 (2017).

-

Engstrom, A. K. & Xia, Z. Lead exposure in late adolescence through adulthood impairs short-term spatial memory and the neuronal differentiation of adult-born cells in C57BL/6 male mice. Neurosci. Lett. 661, 108–113 (2017).

-

Stewart, W. F. et al. Past adult lead exposure is linked to neurodegeneration measured by brain MRI. Neurology 66, 1476–1484 (2006).

-

O’Bryant, S. E., Edwards, M., Menon, C. V., Gong, G. & Barber, R. Long-term low-level arsenic exposure is associated with poorer neuropsychological functioning: a Project Frontier study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 861–874 (2011).

-

Seo, J. et al. Lead-induced impairments in the neural processes related to working memory function. PloS One 9, e105308 (2014).

-

Cervantes, M. C., David, J. T., Loyd, D. R., Salinas, J. A. & Delville, Y. Lead exposure alters the development of agonistic behavior in golden hamsters. Dev. Psychobiol. 47, 158–165 (2005).

-

Soeiro, A. C., Gouvêa, T. S. & Moreira, E. G. Behavioral effects induced by subchronic exposure to Pb and their reversion are concentration and gender dependent. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 26, 733–739 (2007).

-

Eubig, P. A., Aguiar, A. & Schantz, S. L. Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1654–1667 (2010).

-

Rocha, A. & Trujillo, K. A. Neurotoxicity of low-level lead exposure: history, mechanisms of action, and behavioral effects in humans and preclinical models. Neurotoxicology 73, 58–80 (2019).

-

Cui, B. et al. Chronic noise exposure acts cumulatively to exacerbate Alzheimer’s disease-like amyloid-β pathology and neuroinflammation in the rat hippocampus. Sci. Rep. 5, 12943 (2015).

-

Jafari, Z., Kolb, B. E. & Mohajerani, M. H. Chronic traffic noise stress accelerates brain impairment and cognitive decline in mice. Exp. Neurol. 308, 1–12 (2018).

-

Cheng, H., Sun, G., Li, M., Yin, M. & Chen, H. Neuron loss and dysfunctionality in hippocampus explain aircraft noise-induced working memory impairment: a resting-state fMRI study on military pilots. BioSci. Trends 13, 430–440 (2019).

-

Nußbaum, R. et al. Associations of air pollution and noise with local brain structure in a cohort of older adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 128, 67012 (2020).

-

Herry, C. et al. Processing of temporal unpredictability in human and animal amygdala. J. Neurosci. 27, 5958–5966 (2007).

-

Glade, S. et al. Disaster resilience and sustainability of incarceration infrastructures: a review of the literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 80, 103190 (2022).

-

Pellow, D. et al. Impact of law and policy on prison environmental justice: the 2022 annual report of the prison environmental justice project. https://static.prisonpolicy.org/reports/PPI_Annual_2022-2023.pdf (2022).

-

Bradshaw, E. A. Tombstone towns and toxic prisons: prison ecology and the necessity of an anti-prison environmental movement. Crit. Criminol. 26, 407–422 (2018).

-

Crime and Justice Institute, J.Guevara, M. & Solomon, E. Implementing Evidence-Based Policy and Practice in Community Corrections. National Institute of Corrections (Citeseer, 2009).

-

Liman Center. Seeing solitary https://seeingsolitary.limancenter.yale.edu/ (2023).

-

Lovell, D., Cloyes, K., Allen, D. & Rhodes, L. Who lives in super-maximum custody-a Washington state study. Fed. Probat. 64, 33 (2000).

-

Haney, C. Restricting the use of solitary confinement. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 1, 285–310 (2018).

-

Cloud, D. H., Drucker, E., Browne, A. & Parsons, J. Public health and solitary confinement in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 105, 18–26 (2014).

-

Labrecque, R. M. & Smith, P. Advancing the study of solitary confinement. In: J. Fuhrmann, S. Baier (eds.) Prisons and Prison Systems: Practices, Types, and Challenges, 57–70 (Nova Science Publisher’s, Incorporated, 2013).

-

Labrecque, R. M. & Smith, P. Assessing the impact of time spent in restrictive housing confinement on subsequent measures of institutional adjustment among men in prison. Crim. Justice Behav. 46, 1445–1455 (2019).

-

Morgan, R. D. et al. Quantitative syntheses of the effects of administrative segregation on inmates’ well-being. Psychol. Public Policy Law 22, 439 (2016).

-

O’Keefe, M. L., Klebe, K. J., Stucker, A., Sturm, K. & Leggett, W. One year longitudinal study of the psychological effects of administrative segregation (Colorado: Department of Corrections, Office of Planning and Analysis Colorado, 2010).

-

Kaba, F. et al. Solitary confinement and risk of self-harm among jail inmates. Am. J. Public Health 104, 442–447 (2014).

-

Strong, J. D. et al. The body in isolation: the physical health impacts of incarceration in solitary confinement. PLoS One 15, e0238510 (2020).

-

Williams, B. A. et al. The cardiovascular health burdens of solitary confinement. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34, 1977–1980 (2019).

-

Reiter, K. et al. Psychological distress in solitary confinement: symptoms, severity, and prevalence in the United States, 2017–2018. Am. J. Public Health 110, S56–s62 (2020).

-

Haney, C. Mental health issues in long-term solitary and “supermax” confinement. Crime Delinq. 49, 124–156 (2003).

-

Luigi, M., Dellazizzo, L., Giguère, C., Goulet, M. H. & Dumais, A. Shedding light on “the hole”: a systematic review and meta-analysis on adverse psychological effects and mortality following solitary confinement in correctional settings.Front. Psychiatry 11, 840 (2020). *This meta-analysis found that solitary confinement was associated increased adverse psychological effects, beyond that of general incarceration or presence of prior mental illness.

-

Brown, E. A systematic review of the effects of prison segregation. Aggress. Violent Behav. 52, 101389 (2020).

-

Hagan, B. O. et al. History of solitary confinement is associated with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among individuals recently released from prison. J. Urban Health 95, 141–148 (2018).

-

Favril, L., Yu, R., Hawton, K. & Fazel, S. Risk factors for self-harm in prison: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 682–691 (2020).

-

Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. et al. Association of restrictive housing during incarceration with mortality after release.JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1912516, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12516 (2019). *Exposure to solitary confienment during incarceration was associated with increased risk of mortality during community reentry, especially from suicide, homicide, and opioid overdose.

-

Gendreau, P., Freedman, N., Wilde, G. & Scott, G. Changes in EEG alpha frequency and evoked response latency during solitary confinement. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 79, 54 (1972).

-

U.S. Department of Justice. U.S. Department of Justice Report and Recommendations Concerning the Use of Restrictive Housing. (2016).

-

Lynch, L., Mason, K. & Rodriguez, N. Restrictive housing in the US: Issues, challenges, and future directions. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs (2016).

-

Kapoor, R. & Trestman, R. Mental Health Effects of Restrictive Housing Report No. NCJ 250315 (2016).

-

Fone, K. C. & Porkess, M. V. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of post-weaning social isolation in rodents—relevance to developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32, 1087–1102 (2008).

-

Makinodan, M., Rosen, K. M., Ito, S. & Corfas, G. A critical period for social experience–dependent oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. Science 337, 1357–1360 (2012).

-

Robbins, T., Jones, G. & Wilkinson, L. S. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of early social deprivation in the rat. J. Psychopharmacol. 10, 39–47 (1996).

-

Rosenzweig, M. R., Krech, D., Bennett, E. L. & Diamond, M. C. Effects of environmental complexity and training on brain chemistry and anatomy: a replication and extension. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 55, 429 (1962).

-

Begni, V., Zampar, S., Longo, L. & Riva, M. A. Sex differences in the enduring effects of social deprivation during adolescence in rats: implications for psychiatric disorders. Neuroscience 437, 11–22 (2020).

-

Lavenda-Grosberg, D. et al. Acute social isolation and regrouping cause short- and long-term molecular changes in the rat medial amygdala. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 886–895 (2022).

-

Yamamuro, K. et al. A prefrontal–paraventricular thalamus circuit requires juvenile social experience to regulate adult sociability in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 1240–1252 (2020).

-

Park, G. et al. Social isolation impairs the prefrontal-nucleus accumbens circuit subserving social recognition in mice. Cell Rep. 35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109104 (2021).

-

Liu, C. et al. Altered structural connectome in adolescent socially isolated mice. NeuroImage 139, 259–270 (2016).

-

Sheridan, M. A., Fox, N. A., Zeanah, C. H., McLaughlin, K. A. & Nelson, C. A. III Variation in neural development as a result of exposure to institutionalization early in childhood. Proc. Nat Acad. Sci. 109, 12927–12932 (2012).

-

Mehta, M. A. et al. Hyporesponsive reward anticipation in the Basal Ganglia following severe institutional deprivation early in life. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 2316–2325 (2010).

-

Mackes, N. K. et al. Early childhood deprivation is associated with alterations in adult brain structure despite subsequent environmental enrichment.Proc, Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 641–649 (2020). * Children exposed to instutional deprivation in Romanian ophanages showed alterations in adult brain structure 20 years post- instutitionalization.

-

Sheridan, M. A. et al. Early deprivation alters structural brain development from middle childhood to adolescence. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn4316 (2022).

-

Bick, J. et al. Effect of early institutionalization and foster care on long-term white matter development: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 169, 211–219 (2015).

-

Wade, M., Fox, N. A., Zeanah, C. H. & Nelson, C. A. Long-term effects of institutional rearing, foster care, and brain activity on memory and executive functioning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 1808–1813 (2019).

-

Bos, K. J., Fox, N., Zeanah, C. H. & Nelson Iii, C. A. Effects of early psychosocial deprivation on the development of memory and executive function. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 3, 16 (2009).

-

Bastian, B. & Haslam, N. Excluded from humanity: the dehumanizing effects of social ostracism. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 107–113 (2010).

-

Teigen, A. States that limit or prohibit juvenile shackling and solitary confinement https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/states-that-limit-or-prohibit-juvenile-shackling-and-solitary-confinement (2022).

-

Library of Congress. H.R.4972—118th Congress (2023–2024) https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4972?s=1&r=68 (2023).

-

Lobel, J. & Akil, H. Law & neuroscience: the case of solitary confinement. Daedalus 147, 61–75 (2018).

-

Liberman, M. D. United States District Court Northern District of California Oakland Division https://ccrjustice.org/sites/default/files/attach/2015/07/Lieberman%20Expert%20Report.pdf (2015).

-

McCall-Smith, K. United Nations standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules). Int. Legal Mater. 55, 1180–1205 (2016).

-

U.S. Department of Justice. Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011-12. Report No. NCJ250612 (2017).

-

U.S. Department of Justice. Drug Use, Dependence, and Abuse Among State Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2007-2009. Report No. NCJ250546 (2020).

-

Harcourt, B. E. Reducing mass incarceration: lessons from the deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals in the 1960s. Ohio State J. Crim. Law 9, 53 (2011).

-

DeFreitas, K. D. & Hucker, S. J. in Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine (Second Edition) (eds Jason P.-J. & R. W. Byard) 574–578 (Elsevier, 2015).

-

American Law Institute. in American Law Institute (Washington D.C., 1962).

-

Cornell Law School. M’naghten Rule https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/m%27naghten_rule (2023).

-

Donohue, A., Arya, V., Fitch, L. & Hammen, D. Legal insanity: assessment of the inability to refrain. Psychiatry 5, 58–66 (2008).

-

Jurjako, M., Malatesti, L. & Brazil, I. A. How to advance the debate on the criminal responsibility of antisocial offenders. Neuroethics 17, 1 (2024).

-

Craske, M. G., Herzallah, M. M., Nusslock, R. & Patel, V. From neural circuits to communities: an integrative multidisciplinary roadmap for global mental health. Nat. Ment. Health 1, 12–24 (2023).

-

Raine, A. Antisocial personality as a neurodevelopmental disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 14, 259–289 (2018).

-

Sauve, G., Lavigne, K. M., Pochiet, G., Brodeur, M. B. & Lepage, M. Efficacy of psychological interventions targeting cognitive biases in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 78, 101854 (2020).

-

Baskin-Sommers, A., Chang, S.-A., Estrada, S. & Chan, L. Toward targeted interventions: examining the science behind interventions for youth who offend.Annu. Rev. Criminol. 5, 345–369 (2022). *A comprehensive review that details effective alternatives to incarceration that address public safety concerns as well as serve the needs of youth.

-

Baskin-Sommers, A., Ruiz, S., Sarcos, B. & Simmons, C. Cognitive–affective factors underlying disinhibitory disorders and legal implications. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 145–160 (2022).

-

Baskin-Sommers, A., Curtin, J. J. & Newman, J. P. Altering the cognitive-affective dysfunctions of psychopathic and externalizing offender subtypes with cognitive remediation. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 3, 45–57 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School for providing an interdisciplinary scholarly environment where these ideas can grow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.S. and J.C. conceptualized the manuscript. A.B.S., A.W., C.B.W. and J.C. conducted literature searches. A.B.S. and J.C. wrote the initial draft. A.B.S., A.W., C.B.W., S.R. and J.R.R., J.C. edited and approved the final text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks Robert Morgan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Marike Schiffer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baskin-Sommers, A., Williams, A., Benson-Williams, C. et al. Shrinking the footprint of the criminal legal system through policies informed by psychology and neuroscience.

Commun Psychol 2, 38 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-024-00090-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-024-00090-9

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.