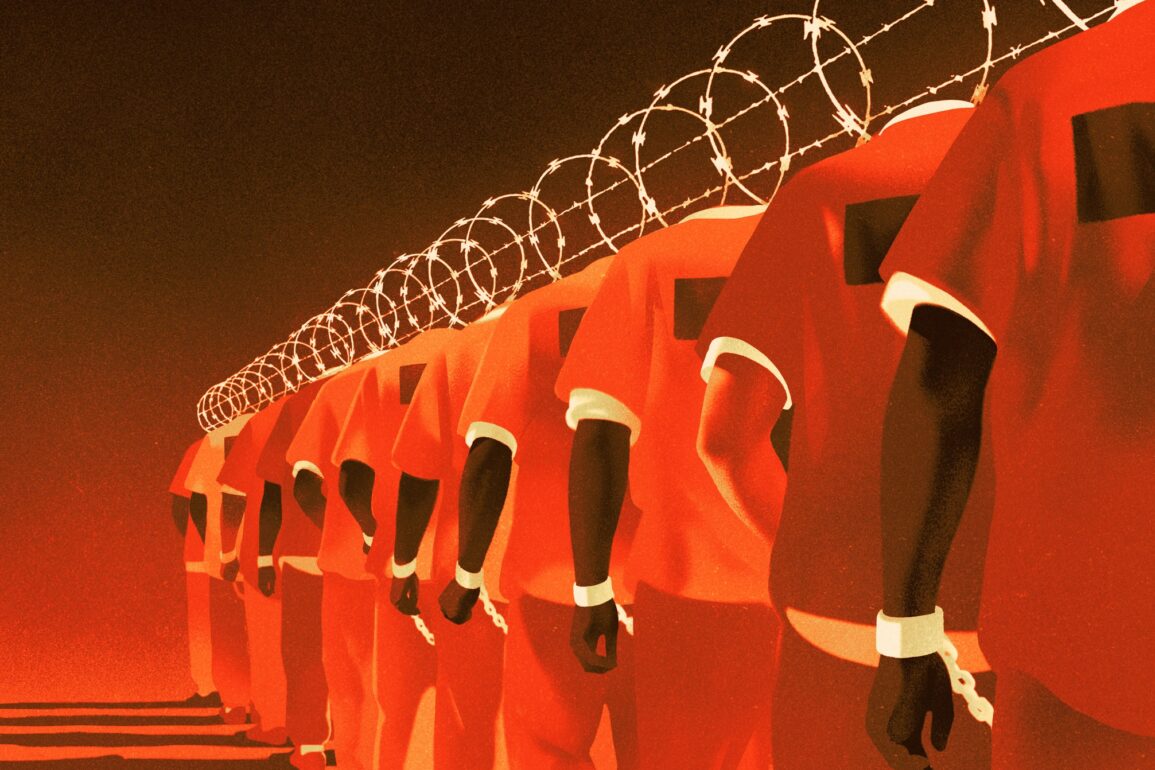

Should We Abolish Prisons?

Every age treats its penal system as natural, inevitable, and regrettable. When men were hanged in the public square, intellectuals explained that the practice was as helpful to the hanged as it was instructive for the audience. Samuel Johnson, as instinctively humane a man as might ever be found, was indignant when, in mid-eighteenth-century London, hangings—often for crimes as petty as pickpocketing—were moved from Tyburn, today’s Marble Arch, to more discreet premises inside Newgate Prison. “Sir, executions are intended to draw spectators,” he said. “If they do not draw spectators, they don’t answer their purpose. The old method was most satisfactory to all parties; the publick was gratified by a procession; the criminal was supported by it.” Public hangings were simply part of street life. Pickpockets attended the hangings of other pickpockets in order to pick pockets.

In retrospect, the hangings are only very partially described as justice done, and much more accurately described as power and class hierarchy enforced. To those born poor, a life of thievery seemed as rational as any other; if it led to the gallows, this was, as horrible as it sounds, a reasonable risk. There were men of the cloth and higher ranks executed—the famous Dr. William Dodd, a friend of Johnson’s and a confidant of the King’s, was hanged for forgery, in 1777—but mostly just to décourager les autres.

Yet the spirit of abolition eventually grew to the point that in the West we now have zero public executions—even prison hangings have been replaced by pseudo-medical procedures—and we are appalled when we learn of them taking place as an instrument of political persecution in Iran. What we do have, however, is incarceration on a scale that, despite recent efforts at reform, boggles the mind and shivers the heart. More people are under “correctional supervision” in the United States today than were in the Stalinist Gulag at its height.

Discover notable new fiction and nonfiction.

In response, a movement has begun for the abolition of prisons—not for prison reform, with fewer inmates in better institutions, but for the outright elimination of incarceration, on the implicit model of the earlier abolition of such things as public hangings, torture, and slavery. Championed most effectively by Angela Y. Davis’s “Are Prisons Obsolete?” (2003), the cause may seem no more realistic than the defund-the-police movement that sang so loudly four years ago, at a cost to progressive candidates. Indeed, in a political moment like this one, worrying about the niceties of progressive reform at all may appear as self-distracting as a beachgoer worrying about sandcastle architecture as the sea pulls back on the brink of a tsunami.

But the process of reform continues through periods of reaction. It was during the worst of the reactionary times in England, after the French Revolution, that Wordsworth wrote his poem “The Convict,” which in a small way advanced a case that even killers had a claim to compassion and rehabilitation. “My care, if the arm of the mighty were mine,” the poet writes, viewing the condemned man, “Would plant thee where yet thou might’st blossom again.”

The argument against prisons can be made as a question of right and wrong, or as a question of effective and ineffective policy. “Mass incarceration as a strategy to address violence is failing,” Danielle Sered writes in “Until We Reckon.” “When we admit to that failure, we become responsible for trying something different. We are not a people who are taking a medication that is working and considering an experimental new drug. We are a people who are taking a medication that is barely scratching the surface of our symptoms and generating compounding side effects that are becoming increasingly unbearable.” A better prescription, in her view, is an approach to justice that’s “survivor-centered, accountability-based, safety-driven, and racially equitable.”

Anyone reading the recent books on prison abolition will be reawakened to the frequent brutality, grotesque ironies, and ingrained indifference of our carceral system. Sered writes movingly of a poor Black family in East New York for whom violence and imprisonment have become commonplace. (“Elwin didn’t know what they were talking about but right as Elijah said yes, he saw one of the other young men flash a gun. Elwin had buried two of his friends in the past two months. He was consumed with grief, but the main feeling he had wasn’t sorrow, but fear. He had come to think that his death by violence was imminent, maybe even inevitable.”) Davis, in her original work and in many essays since, writes with particular intensity of the sexual humiliations and assaults that women inmates face. Meanwhile, “Abolition Labor: The Fight to End Prison Slavery,” a new collection by Andrew Ross, Tommaso Bardelli, and Aiyuba Thomas, offers sage advice from long-term prisoners on the closed circles of long-term imprisonment. “You don’t have to be a criminal to be in an Alabama prison, but by the time you leave, you have been well groomed in criminality,” the inmate Kinetik Justice is quoted saying. “When you steal sugar or chicken from the kitchen, you are stealing from the general population. When you steal the sugar, who loses the cake? It’s not the warden’s cake. It’s not police cake. It’s our cake. You are stealing from us to sell it back to us.”

As the authors of “Abolition Labor” emphasize, the work that Davis has pioneered belongs to the legacy of the great Black intellectual and activist W. E. B. Du Bois—in its shrewd and impassioned observation of minute social detail, and in its feeling for the hidden racial hierarchies of American society. It is also Du Boisian, it must be said, in the way that it gravitates toward class and economic explanations for phenomena not always well suited to them. Davis and others insist that the real villain of mass incarceration in the U.S. must be late capitalism or neoliberalism. In truth, we could empty our prisons tomorrow, and Apple and Google and Amazon and the rest atop the high heap of American enterprise would scarcely notice.

The authors of “Abolition Labor” are determined, similarly, to prove that the exploitation of prison labor—which is nonunionized and generally unprotected even by minimum-wage law—serves the sinister ends of capital. We’re assured that “the prospect of such a cheap, immobile labor pool in close proximity to domestic markets was enticing to the private sector,” which came to view it as “another foreign country, full of cheap and subservient labor, and near at hand.” Yet, they finally concede, “less than 1 percent of incarcerated people are employed today by private companies.” Products from prison labor may slip into the supply lines, but corporations, as a rule, would prefer that they didn’t, since this results in more bad publicity than profit. Inmate labor tends to be done in the service of prisons themselves or government clients like state D.M.V.s. (There’s also the private-prison business, but it’s a shrinking one and houses a small fraction of the incarcerated population.) Plenty of penitentiaries, certainly, were built with local economic motives in mind—ironically, providing employment for the guards in depressed localities to oversee prisoners doing exploitative labor. But these are the kinds of public works that, in other forms, win progressive approval.

There are, in any event, a great many free-market countries in the world, and very few are marked by overstuffed prisons. Mass incarceration remains a distinctively American problem. On the other hand, plenty of anti-capitalist societies have turned to mass incarceration—we speak of the “American Gulag” in honor of another, and nobody looks to Pyongyang for models of penal enlightenment. (Only this month, Amnesty International protested the use of prisons in Cuba as a means of stifling dissent.) Pre-capitalist societies lacked mass imprisonment, but then—what with all the beheadings, beatings, and banishments—the people they considered criminals weren’t around long enough to be imprisoned.

A more abstract argument, derived from Michel Foucault and often cited in the new polemics, holds that incarceration itself is a capitalist-Enlightenment legacy—that the idea of locking people away in an enclosed plant where they do meaningless work is an expression of the capitalist ethic, as much as public hangings were of the feudal one. In the earlier case, punishment was geared toward sporadic displays of terror to enforce the King’s dominion over the population; in our own case, punishment aims to enforce standardized behavior and the rule of the bourgeoisie. Prison is a kind of black-comedic version of a factory: in contrast to the catch-as-catch-can prisons of preindustrial times, everyone is assigned a role and compelled to conformity through regimentation or isolation. The true “profit” made is in the destruction of rebellious spirits. Whatever truth there is in this view—originally directed not at industrialism but at Benthamite forms of utilitarianism, a very different thing—conceptual genealogy probably won’t dismantle the modern prison.

The current system of American imprisonment does reflect the specific circumstances of American life and, in particular, the long wake of Reconstruction. If the link between neoliberalism and mass incarceration seems tenuous, the argument that incarceration is a mechanism that preserves racial hierarchy is unhappily convincing. Incarceration, in Michelle Alexander’s now famous formulation, acts as the new Jim Crow. In New York State, Black people make up around fifteen per cent of the over-all population and almost fifty per cent of the prison population. It is difficult to believe that a future historian will look at these figures and see the abstract workings of justice, any more than we believe that the poor pickpockets of Johnson’s time had dark hearts instead of empty stomachs.

Wherever we place the blame, what is to be done? All the books make a case for a new system. Perhaps surprisingly, Davis’s proposed model of rehabilitation for prisoners caught in the drug wars is the Betty Ford Center, once known as a drying-out clinic for the rich and famous. Her point is rationally made—what is available to the rich ought to be available to the poor as well, and the model we accept when a President’s wife needs rehab should also be offered to an unemployed teen-ager. This would involve huge public costs, but the public costs of prisons are already formidable, and it is more expensive to lock a man up for thirty years than to send him to rehab for six months.

Sered, for her part, is devoted to the practice of “restorative justice.” She is the director of the Common Justice program, which seeks to replace trials and prisons with family circles and compassionate understanding, bringing together those injured with those who injured them, in search of a rational bargain with respect to goods and emotions alike. She tells many moving and persuasive stories of harm short-circuited and offenders kept from prison by restitutive work—none more peculiar and touching than that of a mugger who found himself teaching boxing to his onetime victim.

Sered’s points are sometimes vitiated by the weight of her pieties; her prose suggests someone constantly looking over her shoulder, like a driver going well below the speed limit but still glancing back nervously in fear of a traffic stop, or, anyway, reproach from a captious political ally. What sin might this next sentence commit? For all that, Sered rather overlooks the question of how restorative justice may favor better-resourced offenders. She views it as a kind of people’s justice, seeping upward from Indigenous and marginalized communities robbed of wealth but rich in social capital.

Yet the logic, in pre-state societies, is that if you steal my cattle or kill my son we can enter a cycle of revenge and counter-revenge, or else you can give me restitution for the cattle you stole or the son you killed. Those with more resources could buy more justice—that is, safety from revenge. One reason to promote the modern rule of law is that it aims to reserve retribution for the state, diminishing the crevasse between the people who can pay restitution and those who can’t.

The procedures that Sered advocates have genuine value in part because they aren’t simply reducible to material transactions. In the real world, though, the material part of restoration goes a long way. A version of restorative justice, narrowly considered, is the essence of every billionaire’s divorce settlement. White-collar crime is most often punished by steep fines, which is often taken to be a reparative act: your money will go to prison in your place. Indeed, it’s instructive to watch what happens when the wealthy become caught up in the hyper-punitive system that they can normally escape. We, too, have our Dr. Dodds, arousing our Tyburn yearnings. And so Elizabeth Holmes, the Theranos founder and a young mother, is sentenced to eleven years, and Sam Bankman-Fried, the FTX founder, gets a quarter century—in both cases for nonviolent crimes that caused harm but not physical injury. In the first instance, the financial victims were chiefly people like Rupert Murdoch and Betsy DeVos, who should have known better, and, in the second, nobody appears to have been left poorer at all. Their reckless and illegal conduct calls for sanction and penalties, but people will entrust neither with their money again. Restorative justice for their crimes seems a far saner alternative.

Citing those sentences as an example of the evils of incarceration is, I know from experience, unpopular among the same people who are inclined to be sympathetic to those for whom Davis and Sered so eloquently argue. But we cannot pick among the people we would protect to accord with our own preferences. In Bruce Norris’s beautiful play “Downstate,” we’re asked to extend our sympathies—almost impossibly, one might think—to a group of convicted child molesters sharing a halfway house in Illinois. As each character talks about inclinations and urges succumbed to, they come to seem more human than their pursuers, who, out of pointless panic, prevent them from shopping at the local supermarket. Progressives may struggle even more with mercy toward moneyed malefactors. After all, high-class culprits like Holmes and Bankman-Fried are the rare privileged people who have had a taste of what poor people deal with all the time—talk about justice for all! Can we possibly exempt Ghislaine Maxwell, Bernie Madoff, and others of our Gilded Age goniffs? To ask Angela Davis to hold a place for the banner “Free the Mar-a-Lago One!” seems a little, well, rich. Yet, if the logic of decarceration is to be applied, it ought to be applied—and will have more power if applied—impersonally.

Prison abolition reflects an admirable impulse, forcing us to reëxamine our premises as radically as those eighteenth-century men and women were forced to examine theirs. Yet experience shows that in this country the most effective social way to humanize the punishment of crime is to reduce the incidence of crime. Even Donald Trump, as President, moved toward criminal reform in a time of largely receding violence. That reduction happened, in the past three decades, for mysteriously complex reasons, but one has only to witness how the public responded to the sudden increase in homicides which started in 2020, if now substantially curbed, to see how hypersensitive popular attitudes are. Dismiss this as paranoia or failure of reporting—viewers of TV news who don’t live in cities have a disproportionate sense of the violence to be found in them—but anxiety over social disorder is a fact of democratic political life that cannot be wished away, and it tends to erode the kind of political power that remains the one means toward reform.

At a deeper level, it’s odd to see prison abolitionists like Davis argue, in effect, for transforming prisoners into patients. Treating their actions as mere symptoms diminishes their humanity, their claim to moral agency. It also reminds us that, not that long ago, patients were being reimagined as prisoners. When the deinstitutionalization movement began, Ivan Illich was there to tell us of iatrogenesis, insisting that hospitals produced as much illness as they cured, while Thomas Szasz and R. D. Laing argued for the madness of thinking that madness was a special neurological condition, rather than an understandable response to the horrors of existence. Yet decades of deinstitutionalization have seen a rise in chronic homelessness and mass incarceration, neither of which benefits the intended beneficiaries.

A truly equitable society that invested properly in public health—that assured access to preventive care, community wellness programs, and outpatient management of complex conditions—would keep people out of hospitals. The rate of hospitalization can and ought to be reduced. Should this make us hospital abolitionists? Prisons need to be humanized, but that does not mean that there are no humans in need of imprisonment. Evil exists. Pursuing the recent history of hanging, one reads of a Brit hanged for murder in Singapore—a man who, equipped with a stun gun, befriended tourists under the pretense of being one himself, battered them to death with a hammer, and then dismembered their bodies before stealing their credit cards to buy appliances. He himself thought that he deserved to hang. On the other hand, today one can follow the Instagram page of Adam Roberts, a New York man who, struggling with a serious drug addiction, murdered his father and mother, was sentenced to life, and now works inside as a dog trainer and an articulate chronicler of his activities. Evil exists, but those who perform evil acts need not be themselves wholly evil and incapable of rehabilitation.

There is no plausible world without sanctions for violations of the social covenant. Public order can be, as the abolitionists warn, a form of class policing; it is also a necessity for civil peace. Finding the honest space between these two truths is the key to opening prison doors. If we are to plant human beings in places where they might blossom again, we need to build better gardens. ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.