April 10 will mark one year since President Joe Biden signed a congressional resolution that officially ended the COVID-19 “public health emergency.” The week before, over a thousand people in the U.S. died of the virus.

Declarations like Biden’s aren’t just rhetorically frustrating, they have concrete negative effects. Formally ending the “public health emergency” meant that many of the health measures implemented to keep people safe from COVID ended. For example, Medicare, a public health insurance many disabled people have, has stopped covering free at-home tests, and PCR tests are no longer free. While some health insurance plans still cover testing, many uninsured people will have no access to free tests.

There are so many policies, big and small, that could have been implemented before and during COVID to make the pandemic less deadly. The government could have offered better health communication and education, prioritized measures that protect vulnerable people, provided income for people to be able to stay home, and not allowed pharmaceutical patents to be enforced.

We didn’t end up where we are in a vacuum. COVID didn’t need to be endemic, and decisions like this one to end the emergency will increase sickness and death for the most vulnerable. One of the big reasons that COVID became so deadly was because of policy decisions that see marginalized disabled people as acceptable sacrifices to capitalism. This perspective is mirrored — and amplified — by the U.S. prison system.

COVID and Prisons

Disability and incarceration are strongly correlated, and throughout the book I discuss some of the ways in which the carceral system uses disability as a pretext to take control over the lives of not only disabled people but also nondisabled Indigenous, Black, Brown, queer, trans and poor people, with multiply marginalized people always the most targeted. One reason the pandemic has been especially devastating in prisons is because a majority of incarcerated people are disabled, which places them at a higher risk of dying or getting permanent illness from COVID if they contract it.

The U.S. government’s response to COVID-19 was both predictable and unconscionable. The pandemic laid bare the way health policy affects everything else, and the losses from COVID have not been felt equally by all communities. When adjusted for age, Indigenous, Latino, Pacific Islander and Black American communities suffered significantly higher COVID mortality rates than white and Asian ones. It’s not a coincidence either that the populations that are most at risk of incarceration are the same ones most likely to die of COVID: disabled people of color. This is the outcome of decisions and policies that simultaneously abandon and surveil disabled people.

Logically, then, on a public health level if not an individual one, when COVID first hit, it would have made sense to prioritize the safety of those who are locked up in jails and prisons, nursing homes, and other places with large amounts of high-risk people living together. However, the opposite happened.

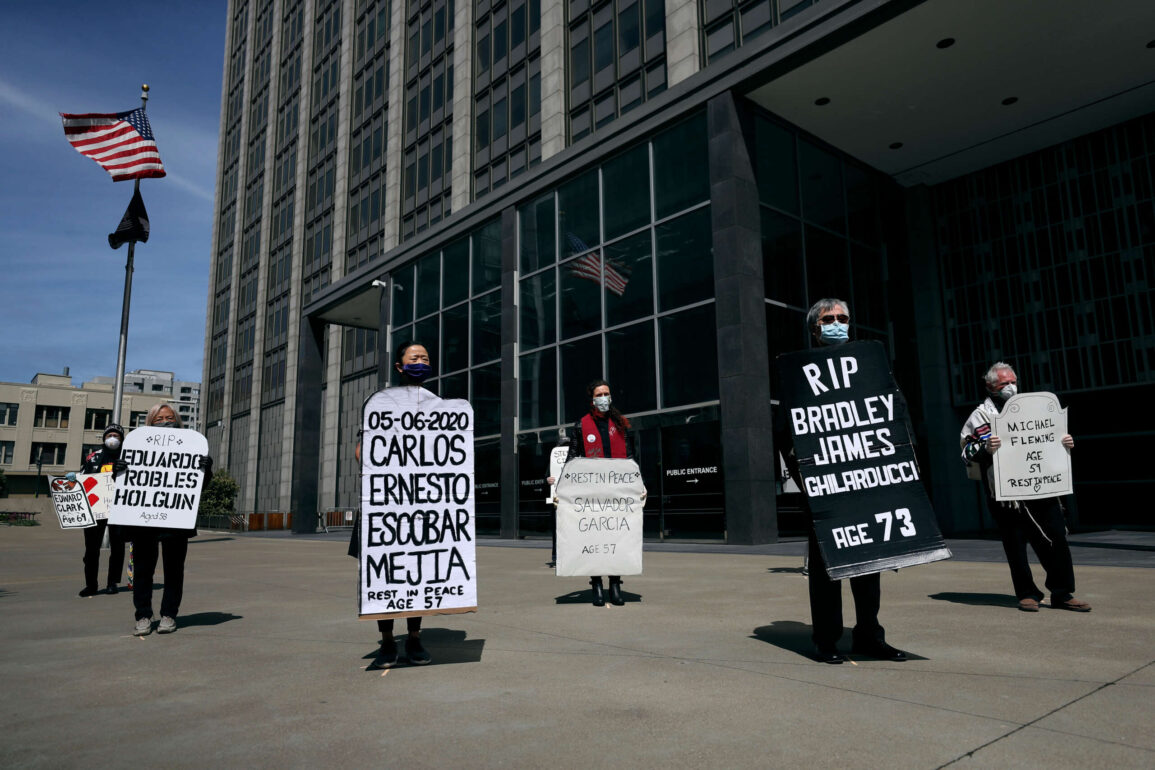

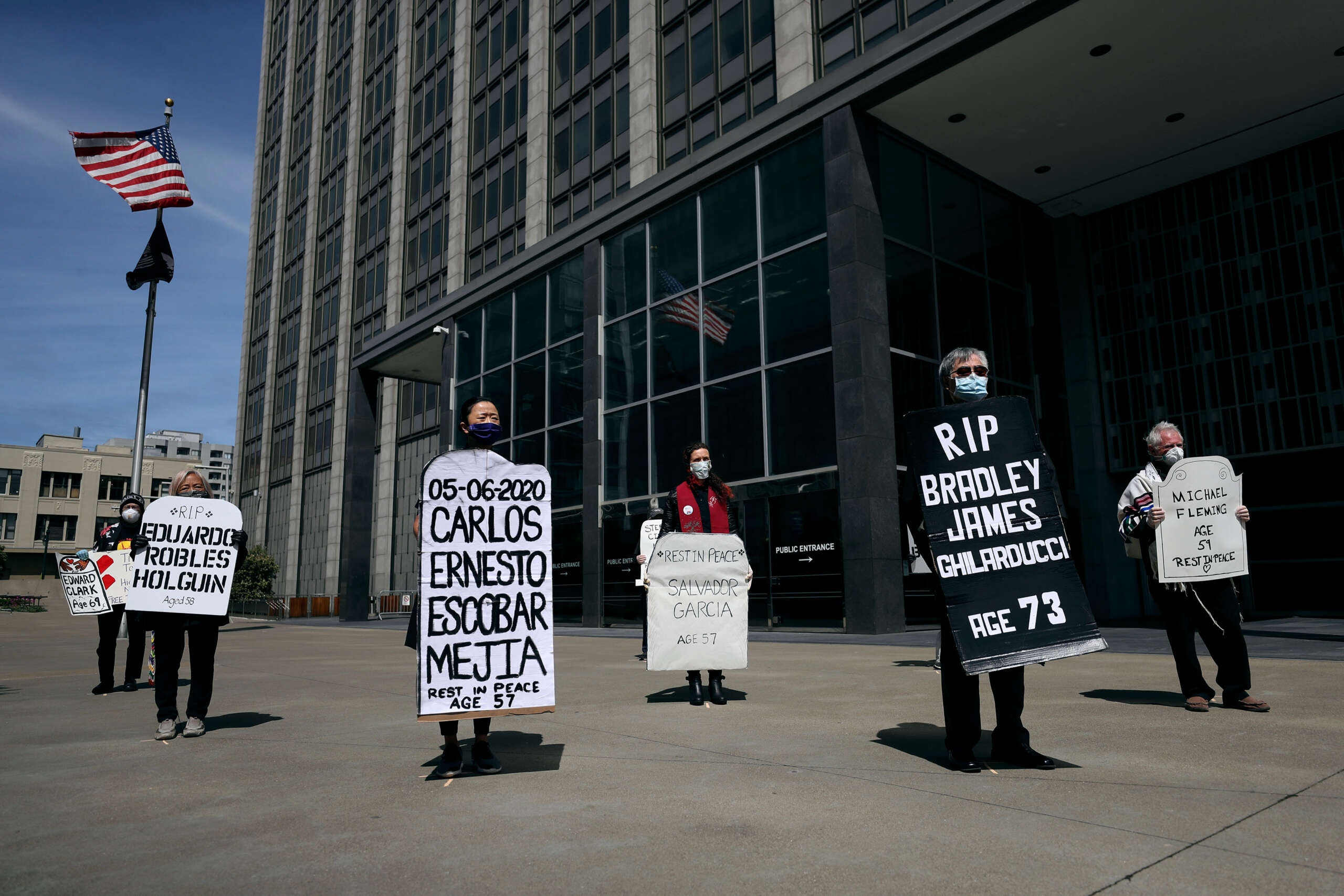

According to the COVID Prison Project, “The majority of the largest single-site outbreaks since the beginning of the pandemic have been in jails and prisons.” One of the many arguments for abolition is the way those in state “care” are sickened and killed. Infections are allowed to run rampant in these facilities because incarcerated people are seen as disposable — a phenomenon I call “carceral epidemiology.”

Carceral Epidemiology

Carceral epidemiology is the way the state — by which I mean the government and other forms of formal and informal control, not one of the 50 states — uses communicable disease as part of the informal punishment of incarceration. While all congregate settings (places where a lot of people live together) have an increased risk of COVID-19 and other transmissible illnesses, in carceral locations, the vulnerability to illness is a feature, not a bug. In other words, the risk of getting sick is an intentional aspect of the punishment. In part this is supposed to incentivize people to stay out of these places, as if anyone would be locked up if they had a choice.

Carceral epidemiology also devalues the lives of people who are incarcerated and institutionalized by failing to protect them from infection and seeing their illnesses and deaths as inevitable or even deserved. This was blatantly illustrated in the way vaccines were prioritized.

Even though people in jail and prison were at as much or higher risk than those in other congregate facilities, they weren’t given access to the vaccine until much later. Though the specific prioritization order varied by state, one study found that “incarcerated people were consistently not prioritized in Phase 1, while other vulnerable groups who shared similar environmental risk received this early prioritization.” When the government shirks its duty to keep people safe — both in times of emergency and in daily life — those who are already vulnerable pay the biggest price.

When you are in state custody, your life is literally at the mercy of decision-makers — people who you’ve probably never met and who (at best) simply don’t care about your well-being. The pandemic proved this.

Writing for the Crunk Feminist Collective, Cara Page and Eesha Pandit explain, “People being held in prisons, jails, and detention centers around the country are acutely at risk given that they are being held in spaces designed to maximize control over them, not to minimize transmission or to efficiently deliver health care.”

As long as the carceral state exists, it will always use health and disablement as weapons — from who gets access to vaccines, to the ways in which governmental neglect leads to “underlying conditions” that make COVID-19 more likely to be deadly, to being forced into congregate settings through laws that criminalize poverty, and on and on. These policies make the difference between life and death, freedom and captivity, and health and sickness.

Even before the pandemic, the lack of universal health insurance in the U.S. caused unnecessary sickness, death and incarceration, and COVID exacerbated this divide. One study found not only that people without health insurance were more likely to contract and die from the virus, but also that community insurance levels also affected COVID spread. “Between the start of the pandemic and August 31, 2020 — health insurance gaps were linked to an estimated 2.6 million COVID-19 cases and 58,000 COVID-19 deaths,” the study notes. “Each 10% increase in the proportion of a county’s residents who lacked health insurance was associated with a 70% increase in COVID-19 cases and a 48% increase in COVID-19 deaths.”

These statistics underscore what we knew even before COVID: the communities someone is a part of have a major impact on their health. Even individuals with health insurance who live in a neighborhood where residents are uninsured (i.e., poor and Black and Brown communities) are at a greater risk of death. This is not because of some inherent difference, but because of policy decisions they had nothing to do with.

COVID-19 showed blatantly how those with the power to make decisions that affect others — like determining who has access to health care and who gets vaccines — are literally deciding which communities get to live and die. While the pandemic made it especially obvious, this isn’t new. The whole carceral system in the U.S. is one (huge) way those in power have decided who gets to live and participate meaningfully in their communities.

COVID is a microcosm of the way disabled people — especially disabled people of color — are both more likely to be in bodies that are vulnerable to illness and that are under state control, a deadly combination. COVID policy is just one of the many strands of the carceral web that disproportionately traps (and often kills) multiply marginalized disabled people.

The pandemic underscores how important it is to understand the ways these systems affect disabled people, especially disabled people of color. The way the virus was handled in jails and prisons is yet more evidence of something that communities of color know all too well: that even brief contact with the U.S. criminal legal or carceral system can be a death sentence. This is just one of the many reasons why abolition is so necessary.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.