A Senate resolution gaining traction among Republicans could send thousands of federal offenders back to prison three years after they were released on home confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

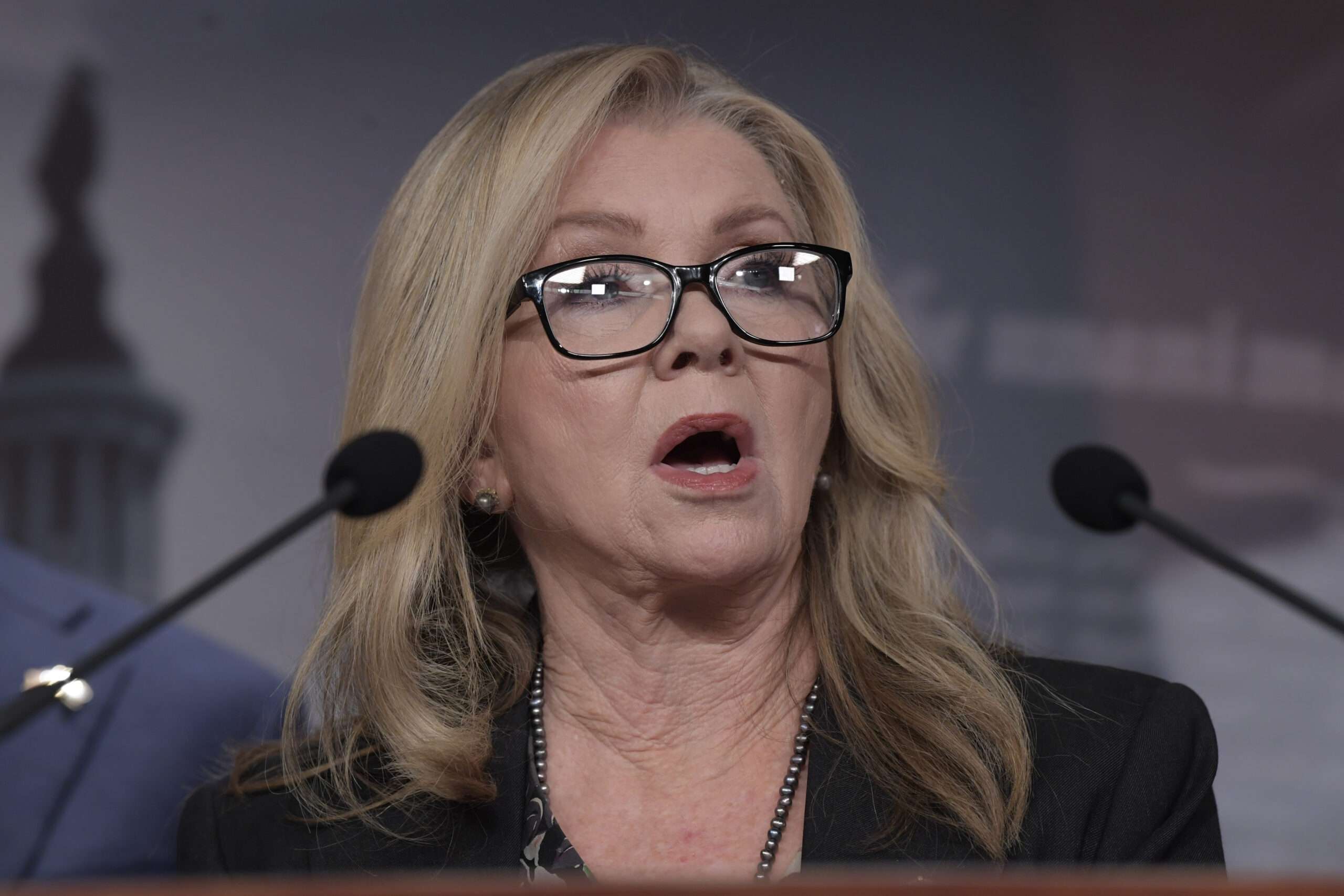

On October 30, Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R–Ten.) introduced S.J. Res. 47, which would overturn a Justice Department rule allowing some federal offenders to remain under house arrest after the end of the government’s COVID-19 emergency declaration.

Congress initially approved the shift of at-risk inmates to their homes in its COVID-19 relief bill, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. According to the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), roughly 5,700 federal offenders are serving the remainder of their sentences at home. Criminal justice reformers argue that the program has been an unqualified success, and that it would be bizarre and cruel to send people who have thrived on the outside back to federal prison three years later.

“While there are certainly plenty of legitimate issues with the BOP that merit senators focusing oversight on the Bureau, CARES Act home confinement is an example of a program that is working—rehabilitating people while holding them accountable, all while driving down costs and maintaining community safety,” says Kevin Ring, vice president of criminal justice advocacy at Arnold Ventures, a private philanthropy group.

The inmates released under the CARES Act have had an extraordinarily low recidivism rate. Of more than 11,000 inmates released to home confinement, who are subject to ankle monitors and strict rules, only 17 had been returned to prison for committing new crimes, according to the BOP. The average overall recidivism rate in the general BOP population is 43 percent.

Those released early to home confinement began to rebuild their lives and reconnect with their families. Among the success stories is Kendrick Fulton. After spending 17 years in federal prison for a nonviolent drug offense, Fulton has gotten his commercial drivers license and a steady job delivering soda.

“I was blessed to be home and not have to really rush to get a job, not have to rush to do certain things, because of my family and the support I had,” Fulton says. “But everybody doesn’t have that luxury that I have of having family.”

There was uncertainty over what would happen to Fulton and others in his situation once the pandemic was over.

In the final days of the Trump administration, the Justice Department released a memo finding that once the federal government ended its COVID-19 emergency declaration, all of those former inmates with remaining sentences would have to report back to prison.

Criminal justice advocacy groups began pressing the Biden administration to reverse that decision. The White House initially declined to do so, instead announcing a clemency initiative that would have targeted only nonviolent drug offenders, leaving thousands of others, such as white-collar offenders, to return to prison regardless of their conduct. But last December the Justice Department reversed course and issued a new memo finding that the BOP had the discretion to leave them under house arrest for the remainder of their sentences.

“It would be a terrible policy to return these people to prison,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said, “after they have shown that they are able to live in home confinement without violations.”

This rule change angered Republicans positioning themselves as tough on crime. Sen. Tom Cotton (R–Ark.), one of the most pro-incarceration members of the Senate, wrote that the reversal “betrays victims and law-enforcement agencies that trusted the federal government to keep convicted criminals away from the neighborhoods that the offenders once terrorized.”

Cotton has co-sponsored Blackburn’s resolution, along with 23 other Senate Republicans, such as Mike Lee (R–Utah), Ted Cruz (R–Tx.), and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R–Ky.). The GOP-controlled House would also have to pass the resolution to void the Justice Department’s rule.

Fulton, who has less than 50 days remaining on his sentence, says the legislators pushing the resolution are ignoring the clear evidence of how well the program is working, noting that it cost taxpayers $40,000 a year for 17 years to keep him incarcerated.

“We’re doing better than people that are all-the-way discharged, and they wanna send us back,” Fulton says. “They know the program is a success. They know it’s a win-win, and it’s saving taxpayer dollars.”

Blackburn’s office did not immediately return a request for comment.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.