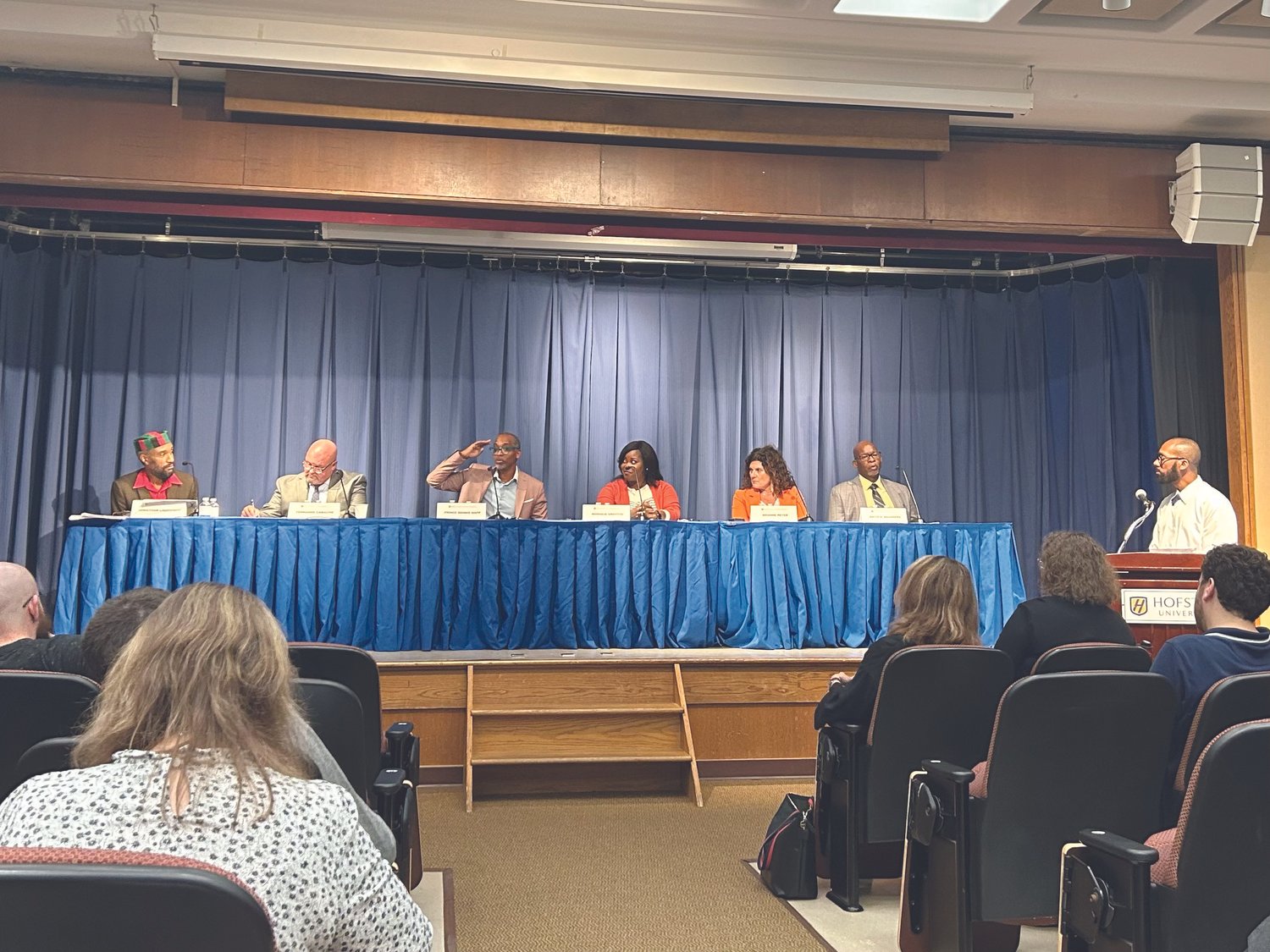

Panelist Prince Dennis Mapp (middle) discusses how he was personally affected by the school-to-prison pipeline. // Photo courtesy of Sophia Guddemi

On Thursday, Oct. 5, Hofstra University hosted a panel of experts to discuss the school-to-prison pipeline phenomenon as well as the role of the criminal justice system within it. The inaugural event was hosted by the Community Reentry Consortium (CRC) in collaboration with Hofstra’s Cultural Center and criminology program. Students from different departments attended the event to learn how they could be a part of the solution to this issue.

“The topic of school discipline and the criminalization of young people of color is one of the most important problems plaguing our criminal legal system today,” said Liena Gurevich, an associate professor of criminology and sociology at Hofstra and organizer of the event.

She explained that the idea for the event came from two of her fellow members of the CRC, a network of organizations and individuals on Long Island who focus on developing resources and solutions for the effective integration of returning citizens. The organization is also composed of Hofstra professors and community members.

Marcellus Morris and Demar Tyson are two formerly incarcerated individuals who have been working with Gurevich and Robert Costello, an adjunct professor of sociology, for many years. The school-to-prison pipeline event was “inspired by Mr. Morris’s and Mr. Tyson’s experiences as being young people who were processed through the pipeline,” Gurevich said.

“We are grateful for their partnership because it is them who advocated for things to happen and for this relationship,” Tyson said in regard to the relationship that has been fostered between him, Morris and the Hofstra community. “This is the first time that something like this has been done.”

“Giving back to younger people, it’s a good experience for me because it’s kind of like redemption,” Morris said. “We have got letters back saying [students] have learned from our speeches. We are reminded that this is what they are going to remember more than the books.”

“It’s my dream. We once laid in cells; those are a lot of long nights, and I was young,” Tyson said. “I became aware that people who went home began to speak at colleges and universities, telling their stories, and I had it in my heart that I wanted to do that as well. I wanted to tell my story to help young minds have an opportunity to hear about the other side.”

He also noted that events have left a long-lasting impact on students’ lives. “If you can reach that one individual or that one class or that one group, then that is a magnificent thing,” Tyson said. “Then I have achieved my life’s goal in an instant. What’s more powerful than saving someone’s life?”

Tyson, who also was the moderator, began Thursday’s event by addressing the crowd of Hofstra students. “Our future leaders, prosecutors, probation and parole [officers], counselors, the people that we are passing the torch to … they can be the disrupters of the school-to-prison pipeline,” Tyson said.

The expert panel assembled by the CRC included six individuals from different areas of the field to help explain the phenomenon, its causes and possible solutions.

“The school-to-prison pipeline is a systemic and disturbing phenomenon in the American educational system,” said Prince Dennis Mapp, head of community and culture at the app Citizen, who has been incarcerated and affected by the problem himself. “The pipeline represents a set of policies, principles and practices … which disproportionately pushes students, specifically those of color, into marginalized communities and eventually into the criminal justice system.”

“We are talking about a larger systemic issue which starts with bias in the larger system,” said Monique Griffith, an assistant professor in the department of psychology. Griffith stated that the larger issue is that the school system funnels special education students and those who have experienced trauma through punishment into the criminal justice system.

Keith D. Saunders, an educational consultant from the Saunders Omnipresent Network Inspiring Americas Youth Inc. and former educator, provided an equation to represent his definition of the school-to-prison pipeline: “Free labor plus time equals profit.”

“Look at the locations of prisons. They are in predominantly Caucasian areas, where that is the main source of income for that community,” Saunders explained. “So, you need the bodies to produce the labor, the labor to produce the product, the product to be sold, for you to make 50 cents an hour. It is a system of capitalism. It’s all about money.”

Furthermore, Mapp added that the amount an individual makes in prison is dependent on their level of education. General prison labor is 11 cents per hour, individuals with a GED make 25 cents and those with college degrees make 45 cents. According to Saunders, this capitalistic system results in products being sold for maximum profits.

“It is the lack of compassion in our court system. We hold the most marginalized and discriminated individuals to a higher standard of conduct in the criminal justice system,” said Fernando Camacho, the court of claims and acting supreme court justice of Suffolk County, when asked his perspective on the causes of the pipeline.

“[The reason] why it is so important that all of us are here is the lack of collaboration between the educational system and the justice system,” said Arianne Reyer, the special counsel for adolescent and juvenile justice for the Nassau County Department of Probation. “Everybody wants to stay in their own box and do their own thing, and they focus on the task at hand. And the task at hand may not be in the best interest of the young people that we are trying to serve.”

One of the main causes Reyer identified was zero-tolerance policies in schools. “There shouldn’t be that direct link from school suspension to arrest to court. There should be some intermediary in the way that is a diversion, that is a way to avoid the stigma of the justice system,” Reyer said. She concluded that one of the largest problems is that the voices of the young people go unheard.

When offering solutions, Jonathan Lightfoot, a professor of teaching, learning and technology and the director of the Center for “Race,” Culture and Social Justice at Hofstra, urged the future teachers and lawmakers in the audience “to center the child, center the student.”

“One of the main root causes is setting expectations on young people and then not giving them any supports to reach those goals,” Reyer said. “We can say to a young person in the court system, ‘If you want to comply with your terms of probation, you have to go to school every day.’ But they aren’t going to school every day if we don’t give them the resources and support to make sure that they get there.”

Saunders recommended that the key to resolving this issue is community. “Let’s become a community with one another again. Let’s communicate with each other again,” Saunders said. “Regardless of race or ethnicity or class or all those other labels put on you, we are human beings. Human beings need love, care, affection, time and energy.”

Students who attended the event said the panel resonated with them because of the relation to their future careers.

“The mention of the word community [made me] feel so honored to be part of an educational program that has the word community in it,” said Katarina Vattes, a second-year doctoral student in the school community psychology program. “I am going to be a school community psychologist, so we have the opportunity to be a change agent.”

Anna Moy, a second-year doctoral student in the school community psychology program, stated that she valued the diverse backgrounds of the panelists. “From people who were in prison to our professor who does so much work in the community – as a person who is mostly white, I think that acknowledging our privilege and how we can extend that privilege to other people who don’t have that is going to be so important,” Moy said. “We are training to be school psychologists and advocacy is what we do.”

“I was very happy with the turnout. That testifies to a great deal of interest in this subject on behalf of the young people,” Gurevich said. “It is wonderful that young people are concerned about other young people. We should make connections; we should make bonds with people in the community despite our differences. It’s worth reaching out.”

For more information about the Community Reentry Consortium and how to get involved, contact Liena Gurevich at liena.gurevich@hofstra.edu.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.