Little is known about the high school student Manar Al Gafiri, an 18-year-old who, according to the exiled Saudi human rights group ALQST, was sentenced in August to 18 years in prison by the Saudi Specialized Criminal Court, in charge of trying terrorism crimes. Al Gafiri was still underage when she was arrested for tweeting in support of political prisoners in Saudi prisons and “human rights defenders, especially women who demand equal rights,” Carlos de las Heras, a specialist on Saudi Arabia at Amnesty International, confirms by telephone. This and other cases, he says, illustrate “a worrying increase over the last year of repression against those who use the internet to express opposition.”

The case of the jailed teenager is not even the most serious sentence handed down in Saudi Arabia for expressing dissent on social media. Since 2017, shortly after the current de facto Saudi leader, Mohammed bin Salman, was named crown prince, these alleged crimes have been considered “cybercrimes” and are likened to acts of terrorism. The same court that sentenced Al Gafiri sentenced a retired professor, Muhammad al Ghamdi, 54, to death on July 10 for his activity on X (formerly Twitter) and YouTube. On his two accounts on X, Al Ghamdi had a total of 10 followers. According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), the Prosecutor’s Office accused him of criticizing the royal family.

Just a year earlier, in August 2022, the same court raised the prison sentence against the PhD student Salma Al Shehab, 35, from six to 34 years, over a tweet that supposedly contained a subtle criticism of a new Saudi public transportation contract. The sentence was later reduced to 27 years. On the same day, another court sentenced another woman, Nourah Al Qahtani, to 45 years in prison for “using the internet to break the social fabric.” In 2022, Amnesty documented 15 cases of people sentenced to between 10 and 45 years in prison solely for peaceful online activities.

The sentence against the professor who, if nothing is done to remedy it, will be executed by the usual method in Saudi Arabia — beheaded with a saber — was confirmed by the crown prince himself on September 20. In an interview with the conservative American network Fox News, the Saudi heir declared: “[This conviction] embarrasses us. But I can’t tell a judge [to ignore] the law. That would go against the rule of law.”

Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy in which the king controls the legislative, executive and judicial powers. There is no separation of powers or rule of law. The crown prince has “more power than any other member of the Saud family since the founding of the kingdom,” in the words of journalists Bradley Hope and Justin Scheck, in their book Blood and Oil. Shortly after Mohammed bin Salman — who currently exercises the power that formally corresponds to his father, the 87-year-old King Salman — was named heir to the kingdom, the new anti-terrorist law was sanctioned, allowing for convictions such as the one affecting the professor sentenced to death.

This new legislation withdrew powers from the Ministry of the Interior and transferred them to the Prosecutor’s Office and the presidency of State Security, two organizations that had previously been placed under the direct authority of the monarch and, therefore, the crown prince. Since September 2022, Mohammed bin Salman has also been the country’s prime minister.

These two organizations that answer to the all-powerful prince have been characterized by intensifying repression. Before Mohammed bin Salman was elevated to heir, never had death sentences or decades-long prison terms been handed down for publications on social media, says HRW.

Saudi Arabia is “the worst state in terms of surveillance in the world,” says Ali Al Ahmed, founder of the Institute for Gulf Affairs think tank, via WhatsApp. Al Ahmed believes that the sentences against internet users are only one visible face of a widespread repression against critics of the regime. “Most of the time we hear about cases like these because outsiders can see that someone stops tweeting or posting,” he says.

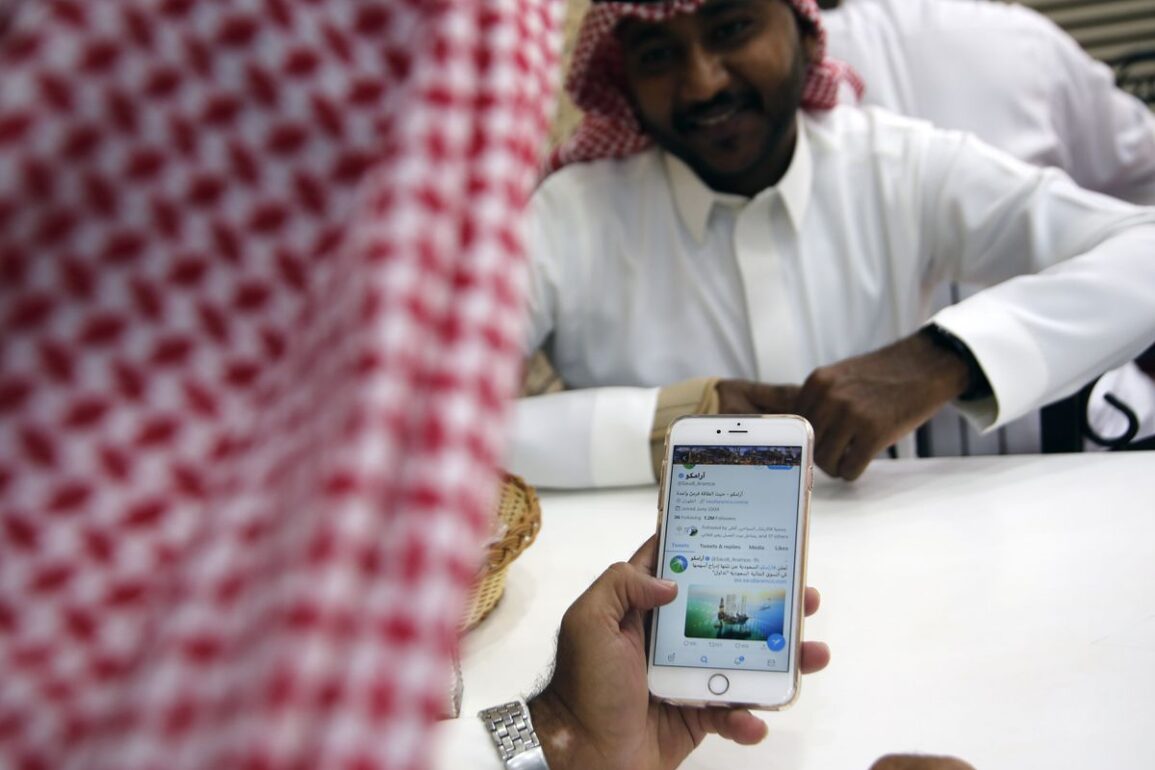

Al Ahmed sued X, then Twitter, in 2020, alleging that two of its employees, Ahmad Abouammo and Ali Al Zabarah, hacked his account between 2013 and 2016 and leaked data from his sources to Saudi intelligence. In a different case in the United States, Abouammo was sentenced to three and a half years in prison for spying for the Saudi government, while Al Zabarah fled to Saudi Arabia. The authors of Blood and Oil claim that the two men were hired by Bader al Asaker, Mohammed bin Salman’s closest collaborator, to identify and spy on Saudi dissidents on Twitter.

Image-laundering effort

Criticism on social media is of particular concern to a crown prince who is very aware of the global impact of these platforms and who, in recent years, has funded a vast operation to launder the image of Saudi Arabia in the service of achieving the objectives set out in the Vision 2030 project, his roadmap for the future of the country. The ultimate goal of this project is to end the almost absolute dependence of the Saudi economy on revenue from oil exports and attract investments, companies and tourists, an objective that is difficult to reconcile with its reputation as a reactionary, fundamentalist and repressive dictatorship that violates human rights.

“Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 tries to offer the world a reformist and open face,” says Amnesty’s Saudi Arabia specialist. With this idea in mind, Mohammed bin Salman has promoted the organization of cultural events, major world sports championships and million-dollar signings of soccer stars. With this and a pretense at liberalization, without democracy or political openness, “they are selling a wonderful image that does not correspond to the life of the Saudis,” emphasizes De las Heras. The repression on social media “has only added to what already existed in the streets.”

This expert deplores how short-lived the timid international ostracism against the Saudi regime proved to be following the murder of dissident Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul in 2018. This past Monday marked five years of that crime, which the CIA attributed to a direct order from Mohammed bin Salman, who now “is once again well received in Europe and the United States.”

“Economic interests prevail,” concludes De las Heras. Meanwhile, Al Ahmed recalls how “most of the surveillance systems, torture, prisons, technologies and tracking techniques [of dissidents used by the Saudi regime], as well as the training of its police, are carried out in the United States, the United Kingdom and France.” He illustrates this with a memory: “When I was arrested for the first time in Saudi Arabia at the age of 14, the handcuffs said Made in California, USA.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.