Sandra Day O’Connor, the Arizona ranch girl who was a fixture in Arizona’s statehouse and judiciary before becoming the first woman to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court, died Friday of complications related to advanced dementia and a respiratory illness.

She was 93.

O’Connor’s 25 years on the high court bench spanned a rightward shift in the court, transforming her role from a cautious conservative to a crucial centrist, legal observers say. After years as the court’s pivotal vote, she returned to Arizona after her 2006 retirement to advocate civic awareness and civility in a time of increasingly brusque partisan politics.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. said of Justice O’Connor: “A daughter of the American Southwest, Sandra Day O’Connor blazed a historic trail as our Nation’s first female Justice. She met that challenge with undaunted determination, indisputable ability, and engaging candor. We at the Supreme Court mourn the loss of a beloved colleague, a fiercely independent defender of the rule of law, and an eloquent advocate for civics education. And we celebrate her enduring legacy as a true public servant and patriot.”

The Arizona Republic, during the state’s centennial celebration in 2012, named O’Connor the most influential Arizonan in tribute to her broad and enduring popularity.

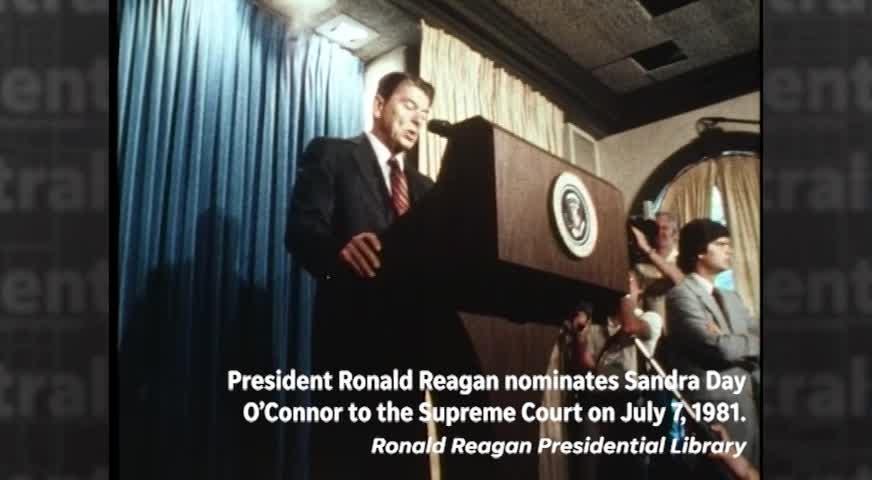

Such widespread appreciation was harder to imagine when she was nominated to the high court in 1981. The historic move by then-President Ronald Reagan generated concern from some Republicans who worried she wasn’t conservative enough, especially on abortion.

Over time, she usually voted with the eventual chief justice, William Rehnquist, a fellow Arizonan with undeniably conservative credentials.

Arizona ranch girl. American legend:Sandra Day O’Connor embodies Grand Canyon State

In perhaps the most consequential case of her career, O’Connor helped form the 5-4 majority to end the recount in Florida that effectively handed the 2000 presidential election to George W. Bush.

At her confirmation hearing and many times after, when asked about the legacy she would like to leave, O’Connor referred to it as “the tombstone question.”

“I hope it says, ‘Here lies a good judge,’ ” she said.

O’Connor rejected plaudits about her importance and influence in her characteristic plainspoken manner.

“I’m no more powerful than anyone else on this court. That’s for sure,” she said not long before retiring.

Lawyers who followed the court would disagree.

More than her colleagues, O’Connor approached cases on their own terms, lending a more unpredictable quality to her jurisprudence, experts said.

By one measure, her vote was pivotal in nearly two-thirds of the closest cases during her tenure, more than 350 in all. It allowed her to help set both tone and direction on such issues as abortion, capital punishment, affirmative action, free speech and separation of church and state.

Experts said legal briefs were often specifically tailored to win over O’Connor.

The appointment to the Supreme Court

Soon after Reagan took office, Justice Potter Stewart gave private notice of his intention to retire. For the new president, it was an opportunity to make good on a campaign promise to appoint a woman to the high court.

At the time, O’Connor was a judge on the state’s Court of Appeals, Arizona’s second-highest court. She may have seemed an improbable pick, but O’Connor had well-placed allies.

Dennis DeConcini, one of Arizona’s two senators, had known O’Connor professionally since the mid-1960s and quickly recommended her for the post.

“I immediately wrote a letter to Reagan and released it to the press for selfish political reasons, saying Sandra O’Connor would be an ideal appointment,” said DeConcini, a Democrat who was a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time.

Barry Goldwater, the state’s Republican senator whom she knew from her own political career, agreed that she would be a good choice and also recommended her to the White House.

So did Rehnquist, who dated O’Connor when they were both law school students at Stanford University. The two had remained friends during his rise to the Supreme Court in 1971.

By chance, Warren Burger, chief justice of the Supreme Court at the time, also knew O’Connor. He met her in 1979 through her friend, former Phoenix Mayor John Driggs, as the families vacationed at Lake Powell together. Burger subsequently named her to national and international legal panels, helping signal her potential. He, too, recommended O’Connor to Reagan.

On July 1, 1981, two weeks after Stewart’s retirement plans were made public, O’Connor met with Reagan for 15 minutes in the Oval Office. She was the only candidate he interviewed, and he announced her nomination a week later.

Publicly, O’Connor, who had no special background in federal law, acted as surprised as anyone.

“I didn’t believe for a minute that I would be asked to serve,” she said in a 2009 interview with C-SPAN. “I went back to Arizona after those interviews and said to my husband how interesting it was to visit Washington, D.C., and to meet the people around the president, and indeed to meet the president himself and talk to him.

“But I said, ‘Thank goodness I don’t have to go do that job.’ I didn’t want it. And I wasn’t sure that I could do the job well enough to justify trying.”

Evan Thomas, a former Newsweek reporter whose 2019 biography of O’Connor, “First,” included access to her personal journals and correspondence, said privately she knew quickly that she was on a very short list of contenders.

Within a week of Stewart’s retirement, an assistant to the attorney general visited the Arizona Capitol and inquired with GOP insiders about O’Connor. Word of the visit quickly found its way to O’Connor, Thomas wrote.

On July 7, 1981, Reagan stunned many when he announced O’Connor as his pick. She held a hasty news conference that day in her Phoenix courtroom.

She didn’t remark on the groundbreaking nature of her nomination and only commented on it when reporters asked her to reflect on it.

“I don’t know that I can. I can only say that I will approach it with care and effort and do the best job that I possibly can,” she responded. “I’ve always tried to do that with any position that I had.”

In Washington, anti-abortion conservatives reacted to her nomination with concern. In Arizona, those who knew her best welcomed the nomination.

Democrat Alfredo Gutierrez, who had served with O’Connor in the state Senate, testified at her confirmation hearing.

“You will go far to find a person equally at home ladling out beans to a work crew in a cow camp, attending a board meeting of a large bank, ironing shirts for her sons, leading the Arizona Senate as majority leader, counseling with the Salvation Army people and presiding as a judge in our court system,” Gutierrez told the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The Senate confirmed her 99-0, and Chief Justice Warren Burger swore her in on Sept. 25, 1981.

State success:O’Connor’s accomplishments in Arizona: Her time as a state judge

On the high court

Her presence added an instant charge to the court.

“The mailbag got delivered to her chambers every day with hundreds of letters from all across the country. It was really quite amazing,” said Ruth McGregor, a former chief justice of the Arizona Supreme Court who served as a law clerk for O’Connor in that first year. “She didn’t have to say very much about it. It was obvious she was the subject of a lot of attention.”

“There is no doubt that my appointment to the Supreme Court was a signal of hope to women throughout America that their dream of sharing in the power base might be fulfilled,” O’Connor told the Chicago Tribune in 1990.

She also helped make small but important concessions to gender equality.

Bias concerns:O’Connor worried about equal treatment in early gay-rights cases

She reworked the federal rules of civil and criminal procedure to make them gender-neutral. She had the honorific “Mr.” removed from justices’ office doors.

As a jurist, O’Connor was seen as serious and straight-laced, seeking careful attention to detail in her opinions and showing an intellectual flexibility to evaluate each case on its own merits.

She favored incremental changes, if any.

“More than most justices, she shied away from formulating broad new social policies,” Arizona State University law professor Paul Bender said when she retired.

“She wanted to not lock the court into interpretations,” said Bender, who argued 15 cases before the court during her tenure.

“She looks for what’s going to work and tries to find solutions that many people can live with. It’s important that she was in the state Legislature and unusual for a Supreme Court justice to have been a practicing politician,” said Thomas, who wrote her authorized biography.

“But maybe even more important, growing up on that ranch … her instinct is to fix the problem and move on.”

Critics said many of her court opinions were more compromising than courageous.

In 1991, she wrote an opinion that scaled back the federal courts’ role in reviewing state-level death penalty cases. Within months, she also expressed concern that the decision could be taken too far, creating injustice.

In 1993, she wrote the opinion in a key 5-4 ruling that found a North Carolina district may have discriminated against white voters. But legal experts said the opinion offered little guidance on how to engineer future districts.

Two years later, she joined the majority in a case that held race could not be the dominant factor in congressional redistricting, but in a separate concurring opinion, she wrote that redistricting could still involve states’ “customary districting principles.”

She reportedly bristled in court at lawyers who signaled her views on the matter seemed a legal jumble.

Deciding on abortion

From O’Connor’s confirmation to her first decade on the bench, abortion was a recurring issue and her views remained inscrutable. In a key 1989 case, O’Connor refused to overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 case that upheld legal abortion rights.

“There will be time enough to re-examine Roe, and to do so carefully,” O’Connor wrote in an opinion that denied Justice Antonin Scalia’s demand to overturn the 1973 case.

A year later, O’Connor signaled that states could go too far in restricting abortion in a case that required parental notification before an underage girl could get an abortion.

In 1992, a Pennsylvania case known as Planned Parenthood v. Casey would erase any doubts about her view on the issue.

Abortion ruling:O’Connor voted to uphold Roe v. Wade despite personal beliefs

At the time, eight of the nine justices were Republican appointees and only two had clearly taken positions supportive of Roe. Not surprisingly, many court watchers viewed Casey as the end of Roe v. Wade.

The eventual 5-4 ruling upholding legal abortion rights was a bombshell.

O’Connor declared that Roe is “a rule of law and a component of liberty we cannot renounce.”

“The woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy before viability is the most central principle of Roe vs. Wade,” she wrote in a lengthy plurality opinion.

However, O’Connor also said some state restrictions on abortion are permissible as long as they do not represent an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy.

“She was looking for a way to deal with a very complex and emotional issue that the country could live with,” Thomas said. “She found a middle way. … She preserved the essence of Roe v. Wade.”

Linda Hirshman, author of “Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World,” took a dim view of the ruling.

“It was typical of O’Connor: meaningless verbiage that tells nobody how to act. It holds the court together, but doesn’t give any guidance for future decision-making,” she said in an interview.

The ruling disheartened those on both sides of the issue. Opponents of Roe were enraged it was affirmed at all; supporters felt the decision left room for states to virtually eliminate abortion rights.

O’Connor’s 1992 ruling gained additional quirky historical value when O’Connor retired from the bench.

President George W. Bush, who arguably owed his presidency to O’Connor, replaced her with Samuel Alito, who as a federal appeals court judge had voted to uphold Casey in full. One passage of O’Connor’s opinion in Casey eviscerated the legal reasoning Alito staked out.

“A state may not give to a man the kind of dominion over his wife that parents exercise over their children,” the opinion read. The state’s law “embodies a view of marriage consonant with the common law status of married women, but repugnant to our present understanding of marriage and of the nature of the rights secured by the Constitution. Women do not lose their constitutionally protected liberty when they marry.”

Asked by NPR in 2013 about the irony that Alito replaced her, O’Connor bluntly refused to revisit Casey or discuss her views on Alito.

“No, I don’t think I’ll try. That’s very sensitive, and I did the best I could in that decision, and I’ll leave it there,” she said. “I didn’t put the two and two together and tell myself, ‘That’s ironic.’ It didn’t matter what I thought anyway. It wasn’t my decision. Time moves on, and we had new appointments.”

Alito, writing for the high court in June 2022, in turn shredded O’Connor’s opinion and took away the constitutional right to abortion. The 6-3 ruling, which will be known as the Dobbs case in Supreme Court parlance, leaves it to the states to set their own laws on abortion.

It was a major legal shift from O’Connor’s ruling but not an unexpected one.

O’Connor believed, Thomas said, that Alito would undo the signature pieces of her work on the Supreme Court. The biggest was on abortion rights, and the other involved affirmative action.

Considerations based on demographics bothered O’Connor, who acknowledged her presence on the Supreme Court owed to her gender. But affirmative action remained a recurring legal issue throughout her tenure.

In 1989, she wrote the majority opinion in a 6-3 case that struck down race-based quotas in municipal contracting jobs. The country can’t move forward, she wrote, by focusing on past discrimination.

“The dream of a Nation of equal citizens in a society where race is irrelevant to personal opportunity and achievement would be lost in a mosaic of shifting preferences based on inherently unmeasurable claims of past wrongs,” O’Connor wrote.

In 1995, she further limited affirmative action in federal matters, holding that any racial considerations had to be narrow and part of a compelling governmental interest.

Those rulings made the 2003 decision in a college admissions case involving the University of Michigan’s law school even more surprising.

Writing for a 5-4 majority, O’Connor held that Michigan’s consideration of race as one of several factors in admissions helped ensure the educational benefits to all of a diverse student body. Even then, she made clear her discomfort with such policies.

“We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary,” O’Connor wrote in her opinion.

Thomas, her biographer, said in a 2019 story for The Atlantic that 14 years later she regretted that timetable. “That may have been a misjudgment,” she told him.

O’Connor’s 2003 ruling was erased in June 2023 by a ruling in a pair of cases that argued affirmative action prevents Asian Americans and others from gaining admission to schools such as Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.

“She said, ‘You know, the court’s going to undo what I did,’” Thomas said in an interview with The Republic. “Sure enough, that happened. It took a while, but it happened, and it’s going to happen again … on affirmative action.”

Dobbs case:Abortion ruling may lead to reappraisal of O’Connor’s work

Early years on the Lazy B ranch

Sandra Day was born March 26, 1930, in El Paso, Texas, and divided her childhood between her grandmother’s Texas property during the school year and the family’s 150,000-acre Lazy B cattle ranch near Duncan, not far from the Arizona-New Mexico line.

In her 2002 memoir, written with brother H. Alan Day, O’Connor described the ranch as “a place of all-encompassing silence,” where hard work required grit to match.

By age 8, she helped mend fences, rode with cowboys, drove a truck and fired her own .22 rifle.

“A rural environment teaches everyone involved in it a sense of personal responsibility,” she told The Republic in a 2009 interview. “You have to do things right, and you have to make things work. When they break, you have to fix what you have.”

She graduated from high school in El Paso at 16 and headed to Stanford University, fulfilling her father’s unrealized dream for himself. She entered college at 16 and obtained an undergraduate degree in economics in three years. After that, she went to law school there.

At Stanford, she dated Rehnquist, her partner in moot-court competitions. He left school early for a clerkship at the Supreme Court in Washington, but he later asked her to marry him in a 1952 letter that remained private until Thomas, her biographer, uncovered it in 2018.

By the time of Rehnquist’s proposal, Sandra Day was dating another law school classmate, John Jay O’Connor III. In 1952, they married, months after she graduated third in her law school class.

Even so, she struggled to find work. She remembered a bulletin board noting law firms interested in interviewing its graduates for jobs.

“I called at least 40 of those firms asking for an interview, and not one of them would give me an interview,” O’Connor told NPR. “I was a woman. They said they don’t hire women. It was a total shock to me. … I had done well in law school, and it never entered my mind that I couldn’t get an interview. That’s the way it was in those days.”

She approached the county attorney in San Mateo, California, because he had hired a woman once. He said O’Connor seemed like a good hire but he had no money left in his budget and no space left in his office.

O’Connor offered to work for free until money was available, which took several months.

“And that was my first job as a lawyer,” O’Connor said. “I worked for no pay and I put my desk in there with the secretary. But I loved my job. It was great.”

After John O’Connor graduated in 1953, he was called to military duty for the Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps. His wife joined him in West Germany, where she practiced as a civilian lawyer.

In 1957, the O’Connors moved to Arizona and later built an adobe home in Paradise Valley. John joined a high-profile law firm, and Sandra, still unable to find better work, set up a private practice with another woman in a small office in Maryvale.

“It was not the high-rent district, and we weren’t exactly dealing with (legal) issues that would wind up in front of the Supreme Court,” she later remembered.

She became a full-time homemaker when the first of three sons was born. The O’Connors were also active in politics, joining the Young Republicans and helping stuff envelopes for Goldwater’s 1958 reelection to the Senate.

When O’Connor was ready to return to work in the mid-1960s, her credentials, practical experience and GOP service brought her an appointment as an assistant state attorney general.

A fast rise in Arizona

By 1969, the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors appointed her to a vacant seat in the Arizona Senate that she had lobbied to get.

O’Connor subsequently won two elected terms and in 1972 was chosen by her GOP colleagues as majority leader, the first woman in the nation to hold such a position.

The same year, O’Connor co-chaired President Richard Nixon’s reelection committee in Arizona.

During her days in the Legislature, O’Connor said she didn’t go drinking or fishing with her male colleagues. Instead, she held social gatherings at the family home in Paradise Valley. It was more than a substitute for the usual backslapping with other lawmakers; she said it helped solidify the personal relationships needed to prevent ideological stalemates.

“I would fix chalupas and Mexican food and all the trimmings,” O’Connor recalled in a 2008 interview with The Republic. “I remember sessions in the living room area with various leaders in the community and talking about provisions for Arizona that would keep it out of debt but allow progress to be made.”

Though she worked to fit in, state politics wasn’t her calling, Arizona’s longtime House majority leader, Burton Barr, said in an interview before his 1997 death.

“Sandra was too detailed, too analytical, too bright for the legislative process,” Barr, a Republican, said. “She’d deal with someone like me, and it would drive her crazy.”

Gutierrez, her Democratic counterpart at the Legislature, said simply, “This place just frustrated the hell out of her.”

In 1974, with Barr’s backing, she was elected a Maricopa County Superior Court judge, marking the beginning of a career on the legal bench.

Four years later, Republican kingmakers, including Barr, urged her to enter the 1978 governor’s race.

“I certainly considered it very seriously,” O’Connor said in a 1992 interview with the Phoenix Gazette. It was then, she said, that she cast her lot with law rather than politics.

In 1979, the man she would have run against, Bruce Babbitt, named her to the state Court of Appeals for a seat she hadn’t even sought. Beyond political expediency, O’Connor benefited from a deep friendship with Hattie Babbitt, the governor’s wife, who was also a lawyer who knew well the challenges of their male-dominated field.

Four months before Reagan tapped her for the Supreme Court, Arizona political insiders still viewed O’Connor as a possible gubernatorial candidate to challenge Babbitt in 1982.

Congressional Quarterly summarized her 18 months on the state appeals court as dry and workmanlike.

“Sandra Day O’Connor was no judicial adventurer. Her opinions quoted liberally from statutes and precedents, rarely added thoughts of her own, and came to terse conclusions. She never wrote a dissent. She showed no hint of ideological fervor.”

It was enough to catch Reagan’s eye in 1981.

A public life in Washington

Sandra Day O’Connor handled the matter with grace, saying she was glad for anything that brought him happiness. John O’Connor died in November 2009 of Alzheimer’s related complications. His wife publicly urged more research into the disease and the issues it raises.

Three months earlier, President Barack Obama gave Sandra Day O’Connor the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. It was the most notable among many honors bestowed on O’Connor.

In 2002, she was inducted into the National Cowgirl Hall of Fame. In 2004, the courtroom in San Mateo County’s historic Redwood City courthouse was dedicated to O’Connor. In 2006, she served as grand marshal of the Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena. Arizona State University renamed its law school after her later that year. There is an elementary school in Mesa named for her, and a high school in Deer Valley as well.

After her retirement, the family adobe was moved, brick by brick, to Tempe to preserve the symbol of civility O’Connor said it embodied.

In 2007, she was named a fellow in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In 1999, Sens. Jon Kyl and John McCain, both Arizona Republicans, sought to name the new federal courthouse in Phoenix after O’Connor, a delicate proposition given that she was still sitting on the Supreme Court.

Kyl acknowledged that naming a federal building for a person still serving was a rarity but justified it this way: “We are seeking an exception for someone who has been the exception all her career.”

Deciding Bush v. Gore

O’Connor’s fateful vote in Bush v. Gore trailed her to the end of her career, in part because the Wall Street Journal reported her husband had said before the case began she viewed a Gore presidency as postponing her retirement.

In April 2013, she mused about the case in a way that might have altered history in 2000.

“Maybe the (Supreme) Court should have said, ‘We’re not going to take it. Goodbye,’” she told the Chicago Tribune’s editorial board a day after the ceremonial opening of Bush’s presidential library.

“It turned out the election authorities in Florida hadn’t done a real good job there and kind of messed it up. And probably the Supreme Court added to the problem at the end of the day.”

Thomas, the Newsweek reporter, said Bush v. Gore bothered her, but not for the reason many assume.

“She thought the country needed the court to bring order to chaos,” he said in 2017. “Justice O’Connor doesn’t express regret about anything. But if she ever expressed regret, it would be about that one case, and I would say mild regret.

“Most of her discomfort comes because the reputation of the court suffered somewhat because of that case, and she is a great institutionalist. She’s a never-complain, never-explain person,” he said.

The Bush case “stirred up the public” and “gave the court a less-than-perfect reputation,” she said. Asked in 2009 about the case by comedian Jon Stewart, she said, “You do your best and live with it.”

In 2013, she told an audience at ASU it was the case she always gets asked about. Then she told the audience not to ask her about it.

O’Connor’s legacy

In her later years, O’Connor wrote a memoir, a history of the Supreme Court and several children’s books. She also founded iCivics, an online program to instill an understanding of government in a new generation. She frequently spoke in defense of an independent judiciary.

She also remained active by sitting on federal appeals cases for years after her retirement from the Supreme Court.

McGregor, O’Connor’s former clerk, had worked with O’Connor’s husband at Fennemore Craig, and she remained close with the O’Connors through the years.

“It’s easy to forget people in a public position have a personal side,” McGregor said, but O’Connor was thoughtful and warm. “She’s just present in her friends’ lives.”

DeConcini, the three-term Democratic senator, said she often turned conversations around, insisting that people tell her how they were doing because she really wanted to know.

In October 2018, in a letter shared by her family, O’Connor announced her retreat from public life due to the effects of dementia.

“How fortunate I feel to be an American and to have been presented with the remarkable opportunities available to the citizens of our country. As a young cowgirl from the Arizona desert, I never could have imagined that one day I would become the first woman justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.”

O’Connor was happy to break barriers for women but didn’t dwell on her gender.

“It really doesn’t come down to how I feel about (a case) as a woman,” she would say. Quoting another female judge’s observation, she said, “At the end of the day, a wise old woman and a wise old man are going to reach the same decision.”

Even so, after giving notice of her retirement, O’Connor quietly expressed hope that Bush would replace her with a woman.

When it didn’t happen, O’Connor admitted to doubting herself.

“I’ve often said it’s wonderful to be the first to do something, but I didn’t want to be the last,” she told C-SPAN. “If I didn’t do a good job, it might have been the last. And indeed, when I retired, I was not replaced then by a woman, which gives one pause to think, ‘Oh, what did I do wrong that led to this?’”

Bush initially nominated John Roberts to replace O’Connor. Rehnquist died before Roberts was confirmed and Bush instead elevated him to chief justice.

Bush then nominated his White House counsel, Harriet Miers, but he settled on Alito after Republicans balked.

While the selection of a man may have been a personal disappointment to O’Connor, the court has undeniably changed.

The first 145 formal nominees to the Supreme Court were all men. After O’Connor, six of the next 19 nominees were women. Five of them were confirmed to the court.

Hirshman, the O’Connor biographer, said she was a paradoxical gender pioneer. O’Connor arrived in Washington just as conservatism grew increasingly out of step with women’s rights.

“With her rather imperfect, fact-based and narrow, centrist decision-making in all the years she occupied the swing vote, she papered over the increasingly deep divide in the American public,” Hirshman said.

Others viewed O’Connor as a moderate who reflected the sensibilities of her time.

She continued that pattern even after leaving the bench.

In 2013, she presided over a same-sex wedding ceremony for two men inside the Supreme Court building. It completed an evolution of gay rights for O’Connor, who upheld anti-sodomy laws in a 1986 case.

The wedding happened as public opinion had come to support gay marriage and within months of a high court ruling that allowed states and the District of Columbia to set their own standards on the issue.

O’Connor outlined her view of the law in a 1987 interview with PBS:

“The wheels of justice grind slowly,” she said. “It is not expected that legislators and courts will jump ahead of the people. … The court is never an absolute end to any issue. It’s more a continuing dialog between the court, the legislators and the nation.”

O’Connor was survived by her three sons, Scott (Joanie) O’Connor, Brian (Shawn) O’Connor, and Jay (Heather) O’Connor, six grandchildren: Courtney, Adam, Keely, Weston, Dylan and Luke, and her beloved brother and co-author, Alan Day, Sr. Her husband, John O’Connor, preceded her in death in 2009.

Former Arizona Republic reporter Jon Kamman contributed to this article.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.