Satoru Abe | John Henry Felix | Carol Malina Kaulukukui | John Dean |

Lynette Jagbandhansingh-Wageman | Deanna Espinas | Glenn Furuya

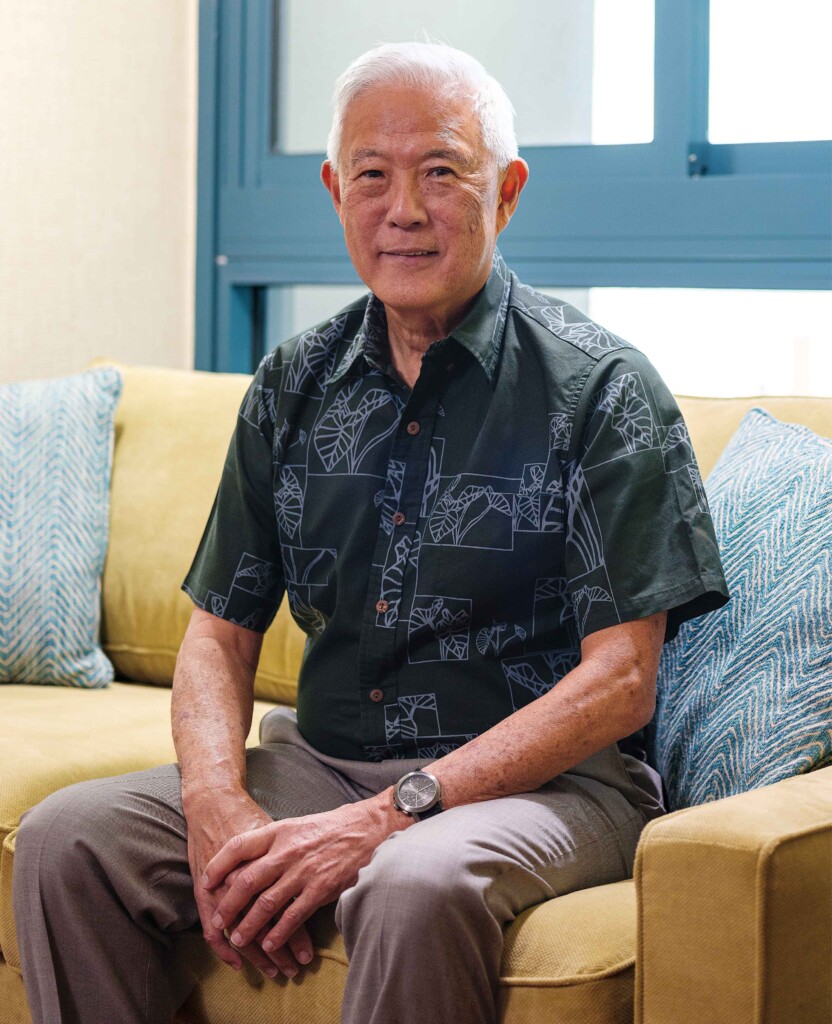

Satoru Abe

One of the premier artists in Hawai‘i has maintained artistic vigor for more than seven decades.

“I make art every day, unless I’m physically unable to,” says painter and sculptor Satoru Abe, now 97. “Looking back at the past 77 years since I’ve been an artist, I cannot believe what I’ve done. I painted, sculpted in metal and wood, made jewelry and painted laser engravings.”

Born in Honolulu and raised in what he calls a “non-artistic environment,” Abe took art lessons while attending McKinley High School but yearned to see more of the world. He studied at the California School for Fine Arts (which became the San Francisco Art Institute) and the Art Students League of New York.

“I traveled to New York and visited the Metropolitan Museum, copied the ‘Head of Christ,’ ” he reminisces. “I finished the painting, brought it home, and gave it away to someone who liked it.”

Today, he is internationally recognized for his art and is best known for his abstract, natural forms. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship as well as a National Endowment for the Arts artist-in-residence grant, and his work can be found in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Whitney Museum of Art, the Honolulu Museum of Art, the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, in private collections, and throughout the state in numerous public works.

Abe says he doesn’t have a favorite sculpture or painting. “To me, every piece I’m working on is my favorite piece.”

One of his best-known works – and most visible – is the sculpture ‘Enchanting Garden,’ which serenely rises out of a fountain at the First Hawaiian Center in downtown Honolulu. Walter Dods Jr., First Hawaiian Bank’s former CEO and a longtime philanthropist, was instrumental in selecting Abe for the job.

“Without a doubt I knew I wanted him to do a piece,” says Dods. “I didn’t give him any direction. I just showed him the fountain.”

The two met around 1970. “I used to go to his home when he lived way, way back in Wai‘anae in a Quonset hut,” Dods recalls.

Dods has amassed a collection of about 150 artworks by Abe. “I think he’s a living treasure, I really do,” says Dods. “His art is unique. It’s special. And he’s such a humble guy. He’s very likable.”

Abe was part of “the Metcalf Chateau,” a group of young Asian American artists who first exhibited together in Honolulu in 1954. It included Abe, Bumpei Akaji, Edmund Chung, Tetsuo “Bob” Ochikubo, Jerry Okimoto and Tadashi Sato. Dods says Abe was “like the dean of the group.”

He has throughout his life been a supporter of up-and-coming artists, buying their works at shows.

Abe had a long marriage with Ruth Aiko Abe, a Satoru Abe textile designer, and he has a daughter, Gail Goto. Ruth died in 2001 after a long illness. He’d been her primary caregiver after she had an aneurysm and stroke in 1988, and even during that painful period, he continued to paint and sculpt.

It’s not easy being 97, though Abe is relatively healthy. He’s happy reading the daily newspaper and credits his longevity to being “optimistic about each and every day I’m alive. I face the day, wondering what I’ll do that day. I look forward to tomorrow.”

While he acknowledges that “art gives meaning to my life and to others,” he notes, “ I do my art not necessarily for others to understand. Art is an indulgence. I don’t look at impacting people with my art. I hope they like it, but it’s more personal satisfaction than anything else. I hope people see me as one of a kind, someone who has done things no one else has.”

John Henry Felix

This prolific volunteer made community service a driving force in his life while navigating a busy, diverse career.

Remember those ads about the Most Interesting Man in the World? John Henry Felix, Ph.D., has a résumé and life so intriguing, it might make that guy jealous.

Felix’s CV includes being chief of staff for William Francis Quinn, the Islands’ last territorial governor and first state governor. Felix was chair and CEO of America’s first revolving restaurant, the La Ronde, built in 1961 atop the Ala Moana Building, and later expanded its parent company to 12 restaurants nationwide.

He helped found and then chaired Hawai‘i Public Radio’s first board. And he worked in labor relations with the Teamsters Local 996 and Hotel and Restaurant Employees and Bartenders International Union, Local 5. And he was on the faculty at Oxford University. He’s also penned multiple books, served on the City Council, and been awarded honorary titles by the governments of Guam, Portugal and Spain. And, of course, he is an Eagle Scout.

At age 93, Felix is the executive chairman at Hawai‘i Medical Assurance Association and still goes into the office twice a week. A bad fall slowed him down in June, he says, but he’s slowly getting back to normal.

Born on O‘ahu, Felix’s distinguished career in service started at age 8, when his mother encouraged him to become active with the March of Dimes, Red Cross and Boy Scouts. “I’ve been involved in all three for 85 years,” Felix says. “My mother was very religious and devoted to the community, to worthy causes.”

Over the years volunteering with the Red Cross, he has worked on behalf of refugees in Africa, Timor and Southeast Asia. He also created a system for blood donations in remote parts of the Pacific and helped establish a prosthetics factory to serve mine victims in Cambodia.

He is a decorated Korean War Army veteran, and also served in the Hawai‘i National Guard. In 1986, his donation of 30 acres of land led to the creation of the Hawai‘i State Veterans Cemetery in Kāne‘ohe. He remains passionate about veterans’ issues, volunteering with the Homeless Veterans Task Force.

A married father of five, Felix lives in ‘Āina Haina. How does he keep up with a busy life, despite his nine-plus decades? “I keep physically fit, 100 pushups a day,” he says. “Even after my injury, I’m back up to 50 pushups.” His exercise regimen also includes stretching, weightlifting and calisthenics, and, he says, maintaining a good mental attitude helps too.

“We have but one life to give,” he reflects, “to our country, our community, and I plan to make the most of those precious years. I want to keep working on serving veterans, and on health issues, making people aware of the importance of maintaining good health and longevity. I hope to work until the day I take my last breath.”

Carol Malina Kaulukukui

The former psychiatric social worker connects mental health treatment with Hawaiian cultural practices.

When it came time to pick a major at the University of Oregon, Carol Malina Kaulukukui took inspiration from her father and chose social work. Her father, she says, worked for an insurance company, but on his own time, helped resolve conflicts in the community.

“The phone would ring every night, asking my father to help mediate. And so when I was looking to see what I wanted to be when I grew up, I just gravitated towards social work,” says Kaulukukui.

After college, she volunteered at a day treatment center for people with mental illnesses in Corvallis, Oregon.

“I became a psychiatric social worker. I worked with people with serious mental illness, including people with schizophrenia and unrelenting bipolar disorder.”

Kaulukukui was asked to help write a grant for a residential program at the facility and though she had no experience with grant writing, she agreed. To her astonishment, the program was awarded a $1 million grant.

“They asked me to run the program, which I did. I got a lot of really good experience, but at some point, it was clear I needed to have a master’s,” she says. So she returned to school and got one, in social work from Portland State.

Kaulukukui then moved to Southern California, where she transitioned to private practice.

“Private practice was so confining and privileged,” she says. “My heart wasn’t there. The other thing that was happening was the part of me that’s Hawaiian was really missing home.”

She moved back to O‘ahu in 1992 and immersed herself in Hawaiian cultural practices.

“I went back to hula. I went back to Hawaiian language. I went back to ho‘oponopono, which is the cultural practice of spiritual healing, and then, interestingly enough, lua, the Hawaiian fighting art. All of these things came together in a way that was cohesive and nurtured my spirit.”

Her extensive knowledge of Hawaiian cultural practices provided valuable insights for a more holistic approach to social work and mental health treatment.

Now in retirement, she keeps busy as a kumu hula at two hālau, one in Kaka‘ako and the other at the Women’s Community Correctional Center in Kailua.

“When I submitted a proposal to teach hula at the prison, I called it ‘Hula as Healing’ because 99% of the women in prison have histories of trauma. Hula is all about storytelling, and part of healing is being able to tell your story to people who will listen with great aloha. You can’t just keep those awful stories inside, you have to be able to share it.”

Most of the dances are based on Hawaiian mythology, whose stories impart meaningful lessons that resonate with the women. For example, many dances are inspired by the dysfunctional family dynamics exhibited by Pele and her sister Hi‘iaka.

“These are the stories that these women have grown up with. And so when we dance the stories of Pele and Hi‘iaka, I say to them, ‘This is about Pele and power and control, about misplaced loyalty and betrayal. Who knows about these things? Who wants to tell their story of power and control relative to Pele?’ ”

Her students find catharsis in performing hula. It makes sense then that their beloved kumu hula’s Hawaiian name, Malina, means soothing and calming.

“I am so glad I’ve lived this long because I was not calm and soothing when I was a kid. I had to grow into my name,” says Kaulukukui, now 80.

“We all grow into our names. It’s not like we’re just automatically like that. Who wants to be given that value? I think working towards that value is what’s important.”

John Dean

This longtime philanthropist proves a high-level finance career and a life of service can be a great match.

John Dean was trying to learn Swahili. However, the universe, or at least the Peace Corps, had other plans, and he was sent not to East Africa, but to Western Samoa (now Samoa).

Finding himself as a volunteer in the country’s treasury department, he says he was fortunate to have learning opportunities. “This was late 1960s, early 1970s, there was an anti-business movement in the U.S., but I came to the conclusion that not all business is bad. It’s a great tool and can be used to improve people’s lives.”

Later, he was accepted into Wharton School, where he earned a master’s in finance, and then started his career at Bank of America.

Dean, now 76, grew up in Detroit, one of seven children, and attended a Catholic school. “It was a blue-collar neighborhood,” he says. “Meat and potatoes, fish on Friday and only on Friday!” Today, he and his wife, Sue, live in Waimānalo and have a second home in California.

After 30 years in the financial industry, where he earned a strong reputation for saving struggling banks, Dean came out of semiretirement in 2010 to work on the turnaround of Central Pacific Bank as chair and CEO. He steered the bank to profitability, earning the title of Hawaii Business Magazine’s CEO of the Year in 2012. Until recently he was chairman emeritus and a director at CPB.

He remains managing partner at Startup Capital Ventures, an early-stage venture capital firm, but is winding that down as well. Dean is now focused on his season of service.

In truth, Dean has been involved in philanthropy for decades, dedicating many of his stock options at CPB to a charitable foundation, and serving on boards such as the Hawaiian Humane Society and ‘Iolani School. But his approach to service today is a bit different.

“I’ve evolved to wanting to spend less time on boards, more to working directly on projects,” he says.

He is especially interested in addressing homelessness, such as with Hui Mahi‘ai ‘Āina, a nonprofit in Waimānalo. He is also passionate about Ho‘ōla Nā Pua, a group dedicated to the prevention of sex trafficking and providing care for children who have been exploited.

“He’s a builder and a creator,” says Jessica Muñoz, CEO and founder of Ho‘ōla Nā Pua. “He’s been an incredible mentor.”

Muñoz met Dean during the capital campaign for the nonprofit that ran in 2016-17, which raised $10 million. “He could see there was a need in Hawai‘i, and around the globe, to deal with this issue,” Muñoz says. Even after the campaign, she says, “he continues to mentor me, and to make connections, ensuring we will have a strong impact.”

“John is genuinely very kindhearted, but he’s also very smart,” Muñoz says. “He’s brilliant when it comes to finance and in business, but also in how things intersect and correlate. That’s what makes him so powerful: his ability to connect so many sectors and to cross the divide with different groups within the community.”

When asked what he’s most proud of, Dean says, “I’d start with my marriage to Sue – 51 years of marriage – and my daughters, my granddaughters.” Apart from them, he says he’s pleased to have been able to do his part to make “this world a better place.”

“It’s an old expression but trying to treat people as you want them to treat you – you’d be surprised how well it works, especially if you are building a team. All organizations need to be demanding but also need to be caring. It’s not an oxymoron. You can be a demanding, caring organization.”

Lynette Jagbandhansingh-Wageman

After a career as a librarian, this 89-year-old stays active with volunteer work. “I wasn’t brought up to sit and do nothing,” she says.

After more than 35 years of helping students as librarian of the Asia Collection at UH Mānoa’s Hamilton Library, Lynette Jagbandhansingh-Wageman has devoted the last 23 years to supporting her community.

At 89, Jagbandhansingh-Wageman can regularly be found volunteering at the UH Mānoa Thrift Shop, where all proceeds go toward scholarships. The shop is run by the Women’s Campus Club, where Jagbandhansingh-Wageman serves as co-president and is in charge of membership.

She also volunteers at Friends of the Library, and with a passion for bromeliads, gives her time at Lyon Arboretum, where she served for years as president of the Hawai‘i Bromeliad Society.

Before the pandemic, Jagbandhansingh-Wageman volunteered at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum as a docent, at First Friday Honolulu, and at Sharon’s Plants in Waimānalo.

“I just want to do whatever I can to make the world a better place,” she says.

While at UH, Jagbandhansingh-Wageman was active as president of the Association for Asian Studies, chair of the South Asian Committee, and presented papers at global conferences including at the Library of Congress, and other international library studies conferences.

She also served on the executive board for the Journal of Asian Studies, and in 1997 started an annual publication, Reference Sources on South Asia.

Jagbandhansingh-Wageman was born and raised on Trinidad in the West Indies, and traveled to the U.S. to study at Park University in Missouri. It was there that she first started working in a library. She came to Hawai‘i in 1961, landing at the East-West Center and playing an integral role in the transition of the institution’s collection to the Hamilton Library. She became Hamilton’s head librarian in 1991, and retired in 2001.

Along with writing numerous letters of support for students seeking recommendations, Jagbandhansingh-Wageman took a personal interest in many Southeast Asia students, helping them to adjust to life away from their native lands and families, inviting them to her home and to events she hosted, and even providing transportation when needed.

“That’s a long stretch for students to take all the courses, then write their (doctoral) paper. They would come to my office, I would help them define their subject, and take them home and feed them,” she says. “They wanted somebody to listen and know they care.”

Many students still keep in touch. Niti D. Villinger, Ph.D., a former associate professor of management at Hawai‘i Pacific University, was a student in the Southeast Asian studies program from 1985 to 1989 and the program’s newsletter editor.

“If I had a research paper or Southeast Asian related topic, she would make book or journal recommendations,” Villinger says. “Because of her own generosity, she had the capacity and time to help students from the Southeast Asian studies program and the EWC. She was interested in getting to know them, almost like a host family.”

Despite her age, and everything she’s accomplished, Jagbandhansingh-Wageman says she doesn’t think she’s doing anything special.

“I’m single, I have the time, and I don’t like to do housework,” she jokes. “I wasn’t brought up to sit and do nothing. I’m just an ordinary person. Whatever talents I have, I try to use them. If I feel I’m capable of doing it, I’ll do it.”

Jagbandhansingh-Wageman encourages others to volunteer, if only for a couple of hours a week. “As long as you’re able, you should be giving back to the world, to the community,” she says.

To this day, if it’s drizzling and she’s driving past a bus stop, she’ll stop and offer a ride to whomever’s waiting. “I want to help whoever comes my way,” she says.

Deanna Espinas

After an unusual career path opened, she spent decades helping marginalized people access knowledge – and their own voices.

“I thought I was going to die; I was truly scared,” Deanna Espinas recalls of her 1981 hiring by the Hawai‘i Department of Public Safety.

She’d earned a master’s degree in library studies and was hoping to work in a school, but positions were scarce. So, she accepted a job as a correctional facilities librarian. “My fear was that I’m a short woman … that I would be prey,” she says. But slowly, she found her place, figured out how to relate to the inmates and served their library needs.

Espinas, now 74, wound up working for more than three decades in correctional settings, retiring in 2014. She helped create and provide law library materials and tools for prisons throughout Hawai‘i. She also boosted recreational reading among inmates, collecting donations from the community of both used books and money to buy new ones.

She advocated for women in prison, connecting with nonprofits and experts on probationary issues, domestic violence and addiction. Espinas also worked with Read to Me International on a program in which incarcerated parents record themselves reading books to their children; afterward, the books and recordings are sent to their kids.

These opportunities, she says, eventually made her realize that working in prisons was the life path she was meant to take. “I had to go this route. I’m glad I did. I’ve always wanted to say, what can I do, how can I get the materials that are needed?”

Born and raised in Honolulu, Espinas now lives in Pālolo Valley. “I grew up in a boarding house behind Tamashiro Market” in Kalihi, she says. Both of her parents were born in the Philippines and immigrated to Hawai‘i, and she joined the Filipino-American Historical Society of Hawai‘i in 2000, where she currently serves as secretary on the board.

She has also been the acting executive director and board president of Hawaii’s Plantation Village and remains a board member today, advocating especially for the Chuukese community. She is the board president for Friends of the Library for the Blind and Print Disabled, and her spiritual life includes being a member of Keolumana United Methodist Church and Faith Action for Community Equity; she also serves on the Hawai‘i District Board of United Methodist Women.

Espinas says she naturally has a lot of energy, takes care of herself with Jazzercise, and credits her husband with doing the cooking and housekeeping. Of her busy life in service, she laughs and says, “My family put up with it; I know no other lifestyle.” She has two sons and three grandchildren and is about to become a great-grandmother.

Espinas is a board member and participates in productions for the PlayBuilders of Hawai‘i Theater Company, which stages community collaborative plays.

“Deanna is a great actress, so creative and extremely present. We all learn from her,” says Terri Madden, the group’s founder, executive director and producer. “She’s always ready to step up and to have marginalized voices heard.” Espinas is performing in the ensemble’s newest production, “The Super Executive Aunties of the Mālama the Caregivers Collective.”

“We’ve been doing a lot of work about caregiving and about aging,” observes Madden. “One of the things I have learned is that we don’t change that much as people as we age. If we are activists in our youth and middle age, we’re going to be activists later in life as well. … And you just don’t want to waste time. You want to make as much of a contribution to your community as you can. That’s what Deanna is doing.”

Glenn Furuya

A local leadership guru shares advice on staying relevant and effective ways to impart knowledge to others.

Glenn Furuya is the founder and president of Leadership Works, which was founded in 1982. Since then, he’s coached several generations of Hawai‘i workers, teaming with Hawaiian Airlines, Kamehameha Schools, Servco and many other companies. At age 74, he’s still robust and dedicated to teaching his Five Seeds of Effective Leadership workshops.

“At this stage in my life and career I want to help the next generation move up into leadership,” he says.

“Oftentimes when we think of leaders, we think of the outstanding young people with fellowships and fancy degrees, the ones destined to be CEOs. That’s not my focus. The everyday managers and supervisors, they are the unsung heroes. They get little recognition yet are the key for how companies survive and thrive. If we don’t grow the next generation, teach them how to lead, then what’s our future?”

Furuya believes in the concept of shoshin, a Zen Buddhism term for a beginner’s mind. “That is where you are constantly learning, staying contemporary,” he explains. “You gotta keep up if you are going to stick around.”

Over your 40 years of practice, have you seen the concepts of leadership change? Or is leadership a timeless quality?

E.O. Wilson had a quote: “We are drowning in information, while starving for wisdom.” You go to Google and type in “leadership,” there are like a billion entries. So, what we really focus on is, what is wisdom? What are those practical, timeless truths? As a leader, it doesn’t matter if it was in the 1800s, 1900s or now. There are certain things that are fundamental. How do you solve conflicts? How do you communicate? How do you apologize if you did something unacceptable?

How can leaders be successful working across generations?

I try to shy away from generational work because it can create biases or prejudices. You can have younger people who are very old-school, after all. So, focus on what is appropriate to the person and the situation. You have to be observant and see what’s in front of you. You have to shed your personal preferences, and then you have to respond appropriately.

What tips do you have for staying vibrant?

The central issue for me is to stay in good health. In your 70s, you’re going to see a cumulative effect of whatever you did up to that point.

I’ve been almost obsessive about taking care of my health. Every morning, I do rebounding (an exercise sometimes described as aerobics on a mini-trampoline) for 30 minutes. I swim four days a week, intensely, like sprint swimming, and take long, rapid walks. For the past 50 years I have stuck to those things.

I eat well. Two-thirds is fresh things like vegetables and fruits, and one-third can be fun foods like cake. I still do a lot of reading – I read about two books a month on leadership. I meditate every day. I spend time with my family. I take short naps, like 10 minutes, and visit the doctor because early detection is your best prevention.

When kūpuna are transitioning to different points in life, such as becoming mentors or moving to volunteer work, how do you coach them to use their leadership skills?

There’s vertical communication; that’s where I’m the boss and I tell you what to do. And then there’s lateral communication, it’s horizontal, we talk story, it’s same-same, you know? The elder has to take on more of a horizontal type of communication. With vertical, (younger people) are going to stop listening, so your good intent to pass on wisdom gets lost because they stop listening and drift away.

Also, in Hawai‘i there’s the East-West Polynesian blend. It’s a unique culture. If you study this blend, out of it comes two patterns of leadership: Asian and Polynesian are a circular leadership culture, relationship oriented, while Western culture is much more linear: “Get it done, and get it done yesterday.”

In Hawai‘i, people have the benefit of understanding the linear, we know how to get the job done, but we’ve also got the circular piece. The best leaders have both.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.