Sing Sing Correctional Facility is 40 miles and a world away from New York City. For almost 200 years, a grim monument to the theory that harsh discipline discourages former inmates from returning to a life of crime.

It’s a flawed theory. A national study by the Department of Justice found that 60% of former inmates are back behind bars within three years.

Which is what gives the movie “Sing Sing” such resonance.

Before he got a taste for acting, Clarence Maclin, who came to be known as Divine Eye, was a violent, knife-wielding, drug dealing inmate at Sing Sing. Now he’s appearing as a version of himself in the critically-acclaimed movie about a prison theater program. The movie stars Hollywood veteran Colman Domingo. in fact, 85% of the cast members in the film are what’s referred to these days as formerly incarcerated.

“I’m lovin’ the movie,” said Maclin. “I’m lovin’ the reaction, the acceptance, the way that people get it.”

“Well, it’s gotta be a big change for you,” I said. “You were always the outlaw, and now you’re the star.”

“Yeah, it’s a big change. It’s a beautiful thing.”

On a recent evening in November, we visited Sing Sing prison with Maclin and John Whitfield, the man he credits for his transformation. Whitfield, known as Divine G, was an award-winning author in prison and a founding member of Sing Sing’s theater program. Maclin said, “I’d probably still be in and out of prison, never would’ve changed my life, had it not been for this brother and his tenacity about getting me into the program.”

CBS News

According to Whitfield, getting Maclin into the RTA program (that is, Rehabilitation Through the Arts) took some doing: “But he eventually came around. And he came around and he experimented, and the minute he got on that stage and got bitten by the bug, I couldn’t shut him up!”

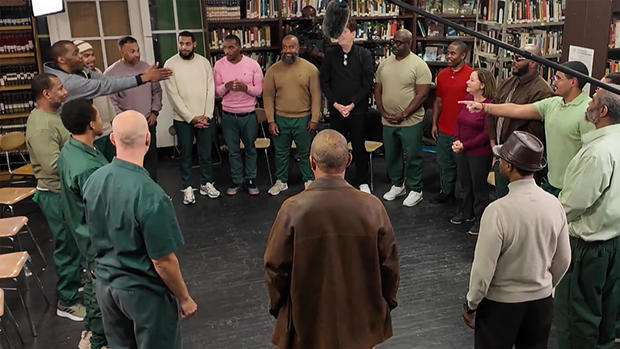

The two Divines, both out of Sing Sing for a dozen years now, returned as guests to meet with members of the current RTA class and a couple of civilian volunteers.

Perhaps nowhere in the world are the actual Divines better known and more widely admired than here.

The actors stood in a circle for a warmup exercise, and the Divines jumped right in. “It’s definitely about communication, about keeping eye contact,” Maclin said. “And we use that particular exercise so that when we’re on stage, we try not to step over everybody’s lines, so you gotta pay attention.”

The chant “chicken … fried … rice,” picked up by each of the participants ricocheted around the circle, faster and faster, until they break up in laughter. One man offered, “It helps you remember where you came from, ’cause all we had was chicken fried rice!”

CBS News

The laughter may be especially jarring to the victims of their crimes, or to the families of those victims. What (to put it more bluntly) does society get out of these RTA programs?

Here’s one answer: The staggering number of former inmates back in prison three years or less after their release – that 60% recidivism rate – is just 3% for those who stayed with the Rehabilitation Through the Arts program.

Divine G was involved with RTA back when success was still very much in question: “Some people’s looking at us like we had four heads. Are you crazy? Going on stage? Talking about ‘To be or not to be’? We didn’t force feed it that fast. You know we had to do it incrementally.”

None of it would have been possible without volunteers from the outside. Almost 20 years ago, Brent Buell volunteered long days at Sing Sing to direct the play that’s at the heart of the film. “Little by little, that getting into the character, [that] first step in empathy, and I’d see the guys eventually saying to one another, ‘What do you think your character feels?'”

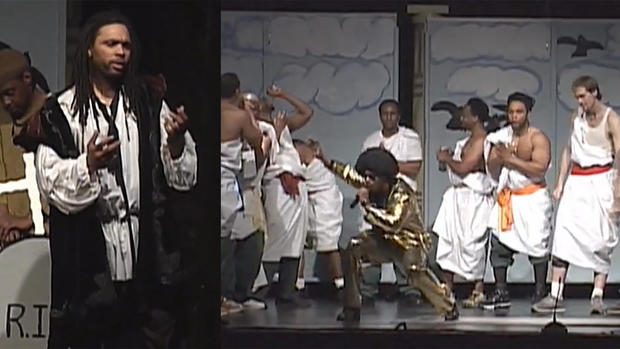

Buell recalls what his actors wanted to play: “The guys said they wanted to do something with Robin Hood. They wanted something with Egyptians. They wanted something with the Old West. They wanted something with Freddy Krueger. They wanted something with gladiators.”

They wanted a comedy that didn’t exist. So, Buell wrote it for them over one long weekend, and called it “Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code.”

Buell recalls one particular breakthrough moment: “In the play, it takes place in the black plague, and the men have been dying. And Alotin Common, the Egyptian priest, says the bodies began to rot. And one of the men inadvertently let out a very … loud sound.”

In other words, he farted. “And the guys started to laugh. Well, then everybody was making, you know rotting noises and things. And they all had permission to be funny. And that was really a turning point in how the whole cast began to see that this is a comedy, and we can really have fun.”

I said, “Somehow, I don’t think this is going to convince America that we have a solution to our penal problems.”

“What’ll convince them is when they meet and are able to talk to the men, that developing of the trust, the respect, the empathy – those men are different people than they were,” Buell said.

He taped the original production, so that the men could share it with their families.

Brent Buell

This was back in 2005, and Brian Fischer, who was Sing Sing’s superintendent back then, recalls that some of his staff were a little skeptical: “All those guys up there carrying on? But as time goes by, the staff accepts them. And more importantly, the other offenders in the prison accept them. They become leaders. They become people that other people want to follow. And it changes the atmosphere and reduces the tension in a prison.”

Now retired, Fischer went on to become New York State’s Commissioner of Prisons. “I think over time, the fact that we were able to put it in other prisons, the fact that it was now acceptable – theater, arts, music [are] now acceptable in prisons that up ’til now didn’t want it.”

Prison life doesn’t normally encourage displays of emotion. RTA made that permissable. Demetrius Sampson told us, “I’ve been gone so long that I forgot what freedom felt like. But when I come to RTA, I felt free again. I left all the regrets and anxiety and mess-ups at the door. And I was able to come in and portray a character with freed-man problems.”

Tim Walker, a lifer, cites the role he played as Macbeth 13 years ago as a life-changing experience. “‘Come fate and champion me unto the utterance.’ That’s Macbeth. That’s the impact that RTA has had on me. That was the first time I ever touched a stage – someone convicted of murder, multiple felonies. I changed my life.”

Michael said, “The public sees us as the problem, and the RTA sees us as the solution.”

Clarence Maclin said, “I came here as an inspiration, to be inspiring to you, and I got inspired by you. Your humanity is monumental. You boys are giants in here.”

Nothing more or less than the promise that they can be something other than they were.

CBS News

For more info:

Story produced by Deirdre Cohen. Editor: Ed Givnish.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.