Liz Truss once advised Rory Stewart to “stop being interesting”. She had a point. By the time he became an MP in 2010, he’d already been deputy governor of an Iraqi province, walked through Afghanistan just after the Twin Towers fell and later commanded a besieged compound in Iraq knowing he’d be executed should the defences be breached. Brad Pitt bought the screen rights to one of his books, earmarking Orlando Bloom to play him in the film.

When Stewart entered parliament, we on the opposition benches were relieved to see that he was only 5ft 8in and (by his own description) scrawny. Another four inches and the Tories would have been unstoppable.

Except that his party never warmed to him, doubting if he was actually one of them. He had joined Labour as a teenager and by his own admission, never voted Conservative. His selection as the candidate for Penrith and the Borders came via David Cameron’s brief flirtation with primaries, where local citizens rather than activists chose the contender.

Penrith residents who feared their town would merely be the launchpad for a ministerial career were soon disabused. Casting an early vote against the coalition government (on Lords reform) condemned Stewart to the backbenches and he threw himself into constituency work: extending broadband coverage, saving the community hospital, having a lift installed at Penrith station, dualling the A66. He saw himself as championing the “big society” only to discover that Cameron’s stratagem was just a slogan.

Austerity was beginning to bite, and when a journalist suggested that his constituency was too prosperous to feel its effects, Stewart replied that parts of it were “pretty primitive” and some farmers used twine to hold up their trousers. Cue a media storm so vicious he contemplated suicide. But the tough hill farmers who he thought he’d insulted were more amused than outraged, and at the 2015 election his majority nearly doubled.

Penance completed, Stewart embarked on a ministerial career that provides the main course in this feast of political insight. Rarely before has the life of a government minister been described in such granular detail or with such literary flair.

Your crude and uncouth reviewer longed for him to tell the game-playing whips to eff off when they insisted he stay in parliament and miss his train to Penrith; to face down the senior civil servant who accused him loudly and mutinously of using International Development as an ego trip. But the man from Cumbria wandered lonely as a cloud through all the turbulence, keeping his temper, doing his job.

He did it best as prisons minister, inheriting a situation where 85,000 convicts were being jammed into 65,000 prison places and where, perversely, a third of prison officers had been sacrificed to austerity. Violence was rife, fuelled by drugs. He knew that access to them was 30 times higher in jails here than in Sweden. With support from his boss, David Gauke, he drew up a programme to fix the broken windows through which drone-delivered drugs arrived regularly, installing scanners, improving search procedures and setting clearer standards.

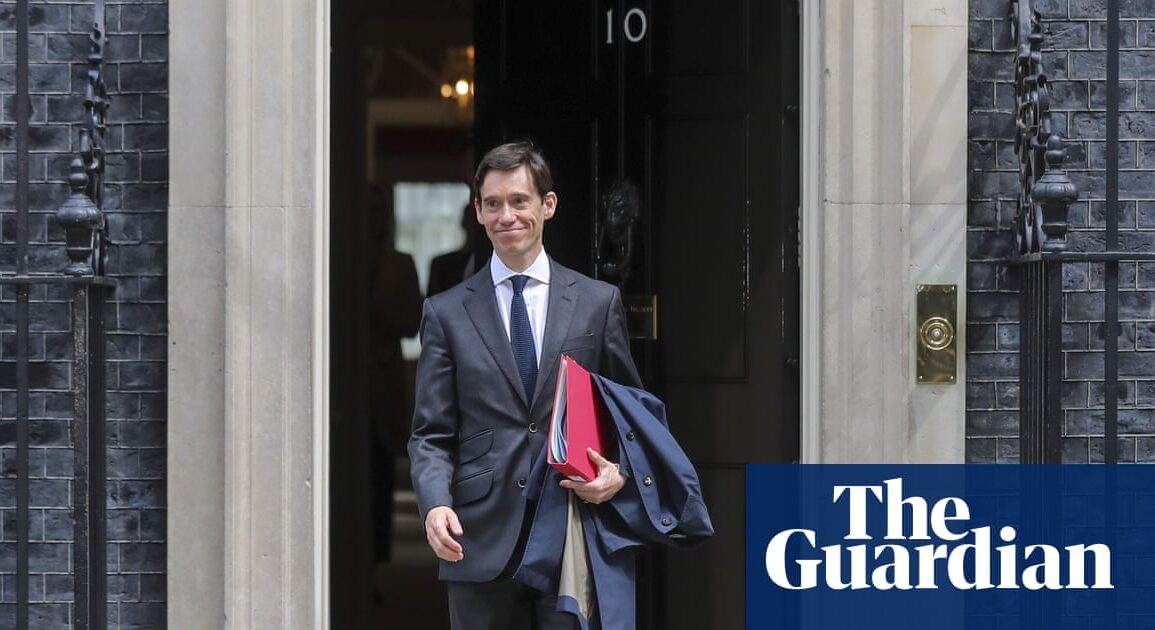

Prison violence was on the way down when Stewart was asked to see the prime minister. With “some of the monarch’s stiff authority” Theresa May promoted him to a cabinet role split between the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, where an unhappy Boris Johnson held the position of foreign secretary. As Stewart tells us: “A man who enjoyed the improbable, the incongruous and the comically over-stated had been trapped in a department whose religion was tact and caution.”

Stewart’s cabinet promotion came during Britain’s period of maximum instability. May completed the carefully negotiated, 585-page withdrawal agreement with the EU and MPs split into two camps – against and against. Johnson and his Mayor Giuliani, Jacob Rees-Mogg, presented “no deal” as a feasible option. Remainers held out for a second referendum. Gove (who among a cavalcade of reprobates, emerges from these pages as a particularly nasty piece of work) compared Stewart’s defence of the agreement to “an Iraqi general defending Saddam”.

Yet Stewart emerges from the carnage a stronger character. He realises that up against the aggressive exaggeration of the European Research Group, his allies on the Tory benches are “like a book club going to a Millwall game”. It doesn’t make him any less intense and he still takes himself far too seriously, but the prisons job and defending what he (and I) saw as a reasonable solution to a 52-48 referendum result ends his “queasiness about confrontational politics”. May goes. Stewart’s wife thinks he should stand for leader.

If it was the kind of open primary that saw Stewart adopted as a parliamentary candidate, he’d have walked it. But it wasn’t, and even if he’d made it through to the final two, the withered husk of the Tory membership was always going to vote for Johnson. In the end Stewart was expelled from the party, along with Churchill’s grandson, two ex-chancellors and six other former cabinet ministers.

It’s tempting to say that he wasted 10 years trapped in the party politics he abhors. But this book is a vital work of documentation: Orwell down the coal mine, Swift on religious excess. We should be grateful it was written and that Stewart never stopped being interesting.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.