Ninth Street NE resident Paul Rodriquez is shaken. His next-door neighbor had his car stolen while the owner of an adjacent home was carjacked. All this after he helped a third neighbor extract a bullet from a child car seat.

Rodriguez wonders when it will be his turn.

Another neighbor, Emily, shares her home security footage of recent carjackings and property damage with law enforcement. Police tell her their “hands are tied,” she said at a public meeting.

“Dismissive” is the word resident Ian Staples uses to characterize the general attitude of Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) officers. “What can we do to activate agencies, including MPD, to help address dangerous behavior and drug dealing before it becomes a violent crime?” he asks.

According to a February 2023 Washington Post-Schar School poll, only 29 percent of DC residents feel “very safe.” In contrast, 44 percent of “Maryland Suburbanites” and 48 percent of Northern Virginians felt similarly.

As of July 23, crime in DC overall was up 29.5 percent compared with the same time in 2022. In particular, violent crimes involving a gun are up 51.7 percent for the period. Homicides are up 13.6 percent.

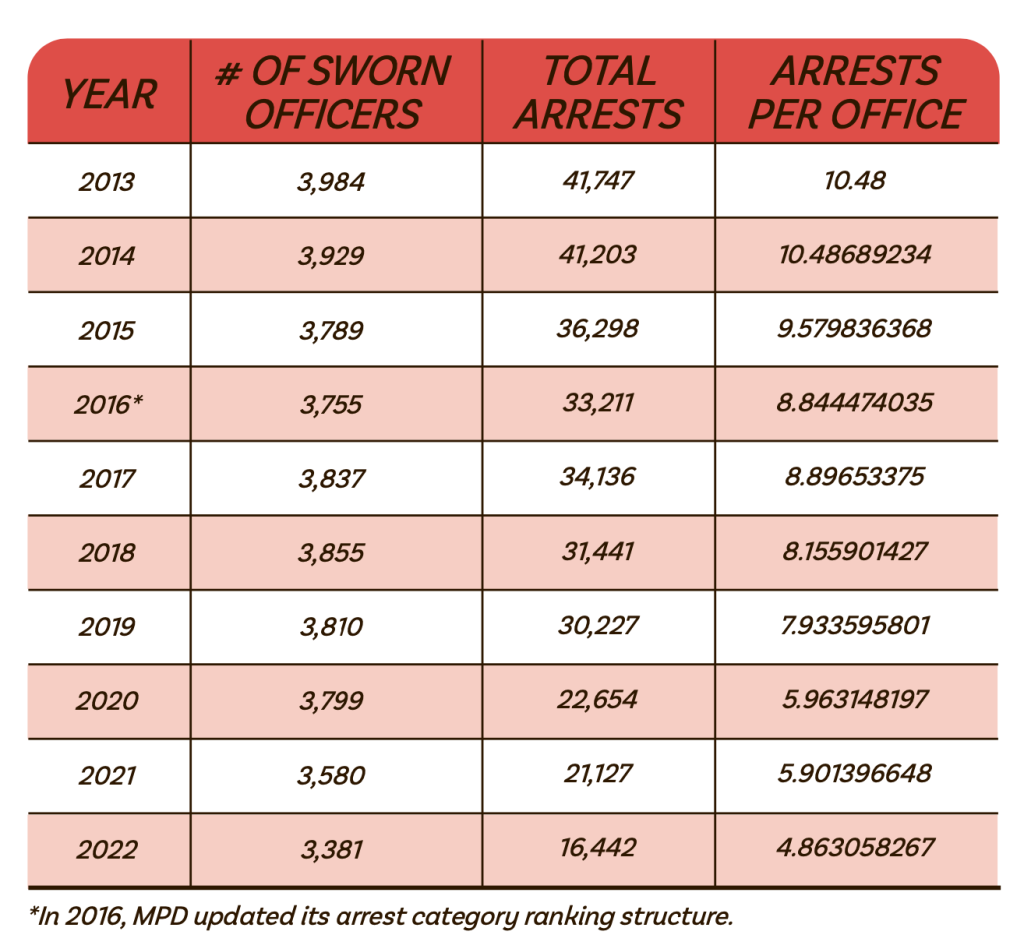

Residents read these statistics and many are afraid. In the District, there is a pervading sense that the city is increasingly lawless and that criminals are no longer being held accountable. That would seem to be true as, in the face of this burgeoning rise in crime, arrests have plummeted. In 2013, MPD made 41,747 arrests. By 2019, the number had fallen to 30,227. In 2022, MPD made only 16,426 arrests. That’s a 60.6 percent decline from 2013-2022. Between 2013-2022, the number of arrests for violent crime also declined by 54.8 percent.

Why is a decline in arrests happening? There are several reasons, some negative and some that might be positive. What this means for public safety in DC is less clear.

Crime Up, Arrests Down

The certainty of being caught is a more effective deterrent to crime than punishment, says the US Dept. of Justice (DOJ). So if there are fewer arrests, there are fewer prosecutions, reducing the fear of being caught and its consequences.

On July 10, as DC Council prepared to vote on public safety legislation, DC Council Chairman Phil Mendelson (D) called on the District’s executive to provide the resources and direction to assist police in closing more cases with arrests. “I believe the most immediately beneficial effect in reducing crime is increasing the case closure rate,” he said in a July 10 media briefing.

But others believe the decline in arrests is not evidence of violent criminals escaping prosecution, but might be a sign of movement towards a new and positive approach to criminal justice and policing. Persons caught for minor offenses may be eluding the grip of the carceral state.

Data

Over the past decade, reported crime in the District has declined year over year. According to MPD reports, reports of crime peaked in 2016, at 37,316 incidents. By 2019 that declined to 34,007; in 2022, MPD logged 27,651 reports. That’s a decrease of 25.9 percent over the past decade. Reports of violent crime are decreasing even faster, falling by 44 percent over the same period, from 6,814 in 2013 to 4,170 in 2019 and 3,805 last year.

So, maybe it makes sense that arrests are declining with crimes. But arrests are falling at a much faster rate. We have seen that over the past decade, total arrests have dropped by 60.6 percent; between 2013-2022, arrests in violent cases declined by 54.8 percent.

Maybe with fewer arrests, officers are focusing resources on the most violent crimes? Not according to MPD data. From 2013-2022, arrests for violent crimes consistently account for between 5.2 and 7.8 percent of overall arrests. That seesaws year-to-year, neither falling nor rising consistently, but the variation is no more than 2.1 percent.

Decline in MPD Staffing

One possible explanation for the decline in arrests is inadequate police staffing.

Fewer officers make for fewer arrests. There were roughly 3,800 sworn officers in 2019. By the end of June 2023, the number had fallen to 3,300. MPD is currently losing more officers than it recruits.

MPD’s ranks are so depleted that the city paid $1 million in overtime is 2022 to compensate for the loss of 500 full-time equivalents, stated DC Police Union President Greggory Pemberton. “We’re not able to do that sort of intake, that initial aspect of public safety, without the proper number of police officers,” he added. “If we’re not identifying who criminals are and arresting those criminals, then nothing else downstream is really going to matter.”

What does inadequate staffing mean for an officer on the beat?

At a monthly meeting of ANC 8F, one First District MPD lieutenant told those present that officers are doing all they can. “The way this department is holding itself together now, piecemeal would be the best description,” the lieutenant said. “We are holding on by a thread, trying not to lose the streets.”

However, lower arrest rates are not just a reflection of a decrease in sworn officers. In 2013, when the force counted 4,010 sworn officers, they each averaged more than 10 arrests. That fell to 7.9 arrests per officer in 2019 and then to 4.86 per officer in 2022.

DC is not an outlier nationally in either its struggle to add officers to the force or in reporting declining arrests. The FBI Uniform Crime Report shows arrest rates falling since the 1990s. US Census data shows that 86 of America’s biggest cities dropped the number of arrests by at least 30 percent from 2013 to 2019.

And every major American city is struggling to keep officers on staff. Philadelphia is about 1,000 officers below strength; Chicago PD budgeted for 13,108 sworn officer positions in 2022 but reported 11,638 as of June 1, 2022.

So, what explanations do police give for declining arrests?

Low Officer Morale

Some residents attribute the decline in arrests to a lack of commitment on the part of officers, according to a 2021 Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) study. Residents complain that officers simply sit in their cars and take little action.

“From what I’m seeing with DC POLICE OFFICERS, DC POLICE NEEDS TO Get OUTTA THE [squad] CARS & POLICE The NEIGHBORHOODS BACK! PATROL THE STREETS!” one woman wrote on social media. “Patrol these side streets where these Car Thefts [are] happening!”

DC Police Union Chair Pemberton attributes decreased police morale to low prosecution rates. According to Federal reports, the US Attorney’s Office (USAO), which prosecutes the vast majority of serious District crimes, declined to prosecute, so-called “no papered,” 67 percent of arrests in 2022.

“…[It’s] completely unrewarding and unvalued, because even if you got out and do your job, the person is right back out the next day and laughing at you, and the neighborhood blames you for not getting the job done,” Pemberton said.

Also officers are often reluctant to engage out of fear of being accused of using excessive force, which Pemberton argues is often unavoidable. He cites an April 25, 2023 interaction between an officer and a teenager captured on a Body Worn Camera (BWC). An officer places his hand on the neck of the girl as she attempts to bash her head against a brick wall.

Neck restraints are forbidden under DC law. The officer was therefore placed under investigation for serious use of force, Pemberton said. However, to many, including himself, this tactic looked like reasonable, measured police work. This scrutiny makes police reluctant to get involved in situations where things might get physical, he said.

There are neighborhoods where making an arrest is very likely to get physical, either because the individual resists or bystanders intervene, said Pemberton. These are often the same neighborhoods where residents are deeply distrustful of the police.

Focus groups conducted among residents of majority Black Wards 7 and 8 for the 2021 MPD PERF Report reported experiencing aggressive and disrespectful styles of policing not seen elsewhere in the District. In particular, they cited so-called “jump outs,” in which officers quickly pull over and approach pedestrians for pat-downs without reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

Is The Decline in Arrests Good?

Research appears to link lower arrests to higher crime. However, critics of the justice system say a decline may reflect positive changes that are happening in policing.

Executive Director of the DC Office of Police Complaints (DCPC) Michael Tobin agrees that fewer officers lead to fewer arrests, saying it is “just basic math.” However, he also sees anecdotal evidence that officers are making fewer discretionary arrests. He attributes this to “all the social influence that we’ve had on policing and police misconduct and police oversight.”

For example, an officer can choose to help a person experiencing a drug overdose to treatment services, rather than arresting them, Tobin says. Police often detain persons on suspicion of gun possession or based a “lookout” description. Innocent people often get angry. What starts as a verbal back and forth can rapidly escalate into a scuffle. However, an officer can deescalate a situation, Tobin says, often by simply walking away. This appears to be happening more often, he said.

Despite the decline in arrests and anecdotal evidence of de-escalation, police complaints are up 17 percent compared to last year, Tobin acknowledges. He attributes this in part to a return to pre-COVID levels of police contact. The standard provision of BWCs have also, Tobin believes, generated increased complaints due to the existence of recordings that might substantiate them.

Declining rates of prosecution and arrests are a good sign, said Patrice Sulton of DC Justice Lab. High arrest and prosecution rates of the past, Sulton argues, were “a result of the massive amount of proactive and unconstitutional policing in the city.” That had a disproportionate effect on Black residents.

Logically, if policing are making fewer arrests, that should mean fewer negative interactions between Black residents and the police overall, a positive effect.

Is It the Right Question?

But what do arrest rates truly tell us? One thing they do not tell us is the true extent of crime.

Many victims are not using police as first contact with the justice system, says Naida Henao, strategic advocacy counsel at Network for Victim Recovery of DC (NVRDC), citing increasing calls to their help line. Only 50 percent of violent crime is reported to police, according to a report from the Justice Center for the Council of State Governments.

Some victims do not want the perpetrator arrested, fearing the arrest will disrupt their safety and security. This is especially true in situations of domestic violence, in which one parent may not want to deprive a child of the other parent; or where the offender’s income is critical to the household and even to having a home.

Many victims have more pressing safety issues to deal with, such as addiction, hunger, housing or critical health concerns, says Henao. Some communities historically have distrusted the police. Justice-involved individuals, she says, may avoid the police out of fear their history will be prioritized over their safety.

This is one reason that activists have called for some police funding to be reallocated to other resources, including non-police personnel who could respond to situations involving crises of addiction or mental health. Without police intervention, runs the argument, arrest is far less likely.

Assessing public safety through the numbers of arrests misses as much as it captures, Henao said.

A Complicated Dynamic

In sum, there is no single reason for the decline in arrest rates, nor is there consensus on the effect of that decline. The reduction in MPD staffing does not appear to be the key driving factor. The USAO’s “no papering” 67 percent of arrests has clearly negatively impacted police morale. Officers also fear being disciplined for engaging physically even when necessary. MPD’s increasing training emphasis on de-escalation may also be a factor.

Some say there are positives to the decline in arrests, given the disproportionate interaction between officers and Black residents. Others caution against using arrests as a criminal justice metric, arguing it ignores vast numbers of unreported crimes and questioning the equation between increased arrests and increased safety.

However, these arguments are cold comfort to Rodriguez and his neighbors, who fear becoming future victims. Nor do they assist MPD officers who find themselves at a loss advising the public.

“We absolutely try everything that we can imagine,” said the 1D Lieutenant at ANC 8F. “One thing is not going to fix it.”

MPD did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this story.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.