To the Editor:

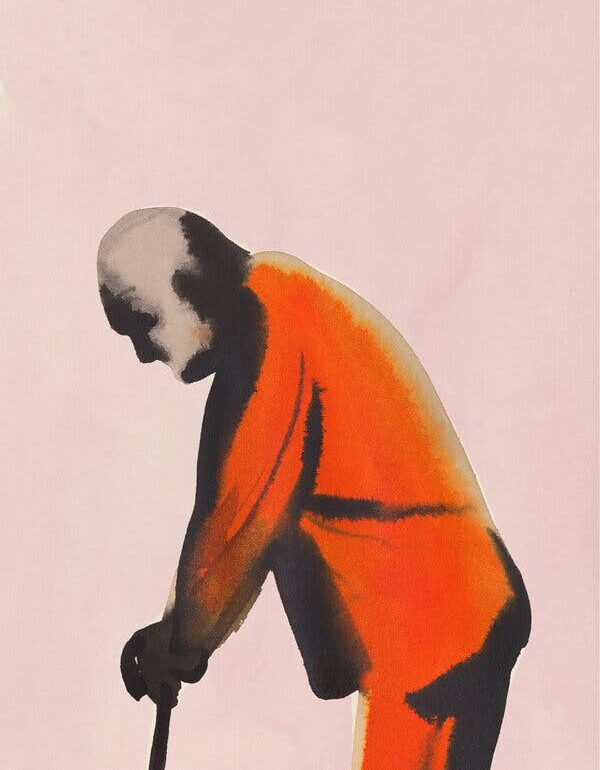

Re “Inside a Dementia Unit in a Federal Prison” (Opinion guest essay, Aug. 13):

Katie Engelhart vividly describes the absurdity and cruelty of incarcerating frail elders with debilitating dementia. It would be a mistake, though, to conclude simply that expanding compassionate release is the answer. Certainly, that’s warranted, but policymakers should be proactive, not just reactive.

As a former parole commissioner, I know that dementia is just the tip of the iceberg of the problem of mass aging behind bars.

Countless people (not just men) effectively face a slow death penalty behind bars because of extreme sentences or repeated denials of parole release despite these individuals’ complete transformations. Far from being helpless, many are violence interrupters, mentors, scholars and artists, including people previously convicted of causing serious harm. They have changed.

Enacting elder parole bills, which do not guarantee release based on age but rather allow older adults to be individually considered for release by a parole board, can help resolve the crisis of aging behind bars, save substantial money, and return people to the community to repair the harm they long ago caused — before they are on death’s doorstep.

Carol Shapiro

New York

To the Editor:

Dementia units in prisons should primarily serve as a conduit to helping achieve compassionate release. As physicians volunteering with the Medical Justice Alliance, we review the medical care of numerous patients with dementia who are undiagnosed and untreated in the prison system. Patients wake up unsure why they are in prison, hoping that President Nixon might pardon them.

We must consider the high cost of normalizing the imprisonment of elderly patients with dementia. Financially, developing “dementia-friendly” prison units incurs significant costs; that money could instead be used to improve community resources such as nursing facilities. Ethically, we must grapple with punishing people who do not pose a threat to others and are unable to understand why they are being punished.

Compassionate release laws at the state and federal levels should make dementia an explicit criterion for early release. Facilities should also screen older patients for dementia on a regular basis and develop protocols for requesting compassionate release and expediting placement in memory care facilities. The U.S. prison population is aging and change is urgently needed.

Caitlin Farrell

Nicole Mushero

William Weber

To the Editor:

As a person who has served three federal prison terms for antiwar protests for a total of almost three years, I found myself shaking my head that the Federal Bureau of Prisons maintains Federal Medical Center Devens to hold men with dementia.

The essay noted that most of the men in the dementia unit have no memories of their crimes or why they are incarcerated, yet few are deemed eligible for compassionate release. The United States incarcerates nearly two million people in our thousands of jails and prisons. The U.S. prison system is primitive, lacks redemption and only metes out punishment. The term rehabilitation is simply not part of this cruel system.

In my time in more than a half dozen federal prisons, I never met a man I would not have to my home as a dinner guest. Our jails and prisons are filled mostly with people convicted of nonviolent crimes. Many — perhaps the majority — of incarcerated people are poor, mentally ill or substance abusers. Most need medical treatment, not incarceration.

I agree with F.M.C. Devens’s clinical director, Dr. Patricia Ruze, who thinks it would be “totally appropriate” to release the whole unit on compassionate grounds and relocate the men to community nursing homes.

I’d go one step further: Let’s release all nonviolent people from prison with appropriate community support to help them prosper and avoid recidivism, as well as offer programs of human uplift to the remaining prisoners using the money we save by closing the prisons we will no longer need.

Patrick O’Neill

Garner, N.C.

Living Well, and Pursuing One’s Passion, With Parkinson’s

To the Editor:

Re “Pianist Adapts His Life to Parkinson’s” (Arts & Leisure, Aug. 13):

Thank you for demonstrating how the pianist Nicolas Hodges is adapting to life with Parkinson’s disease. Mr. Hodges is testament to the fact that it is possible to continue to live well with Parkinson’s, and the article highlights two key ways to manage symptoms: consistently taking medications (dopamine) and reducing commitments or stress. Exercise and physical activity are also critical to managing symptoms.

Recent research published by the Parkinson’s Foundation shows that the number of people in the U.S. diagnosed with Parkinson’s annually has increased by 50 percent, from approximately 60,000 to 90,000. This means that every six minutes, someone in the U.S. is diagnosed with the disease and may encounter similar challenges to those faced by Mr. Hodges.

Further funding to support research and drug development are needed in order to find a cure, and the Parkinson’s Foundation and other organizations work tirelessly to advance this.

In the meantime, we applaud Mr. Hodges for speaking about his experience with the disease and continuing to pursue his passion. Play on, Mr. Hodges.

John L. Lehr

New York

The writer is president and C.E.O. of the Parkinson’s Foundation.

The ‘Absurd Contradictions’ of the Migrant System

To the Editor:

We have millions of square feet of office space no longer being used and tens of thousands of homeless people and displaced immigrants needing shelter. Many employers cannot fill open jobs while the talents and proven determination of immigrants sit untapped in detention.

We can strengthen our economy and confirm our commitment to human dignity and decency by correcting these absurd contradictions.

It would be far more cost-effective to use the migrant detention system funds to create a system where people can be quickly helped and trained to be productive contributors to society instead of expensive drains on us all.

Even if common decency is not a motivation, pure selfish economic need dictates that we end the waste and do the right thing.

Michael E. Makover

Great Neck, N.Y.

A Civilized Argument

To the Editor:

Re “Imagining the Face-Off in Trump’s Jan. 6 Case,” by David French (column, Aug. 12):

I started feeling odd as I read Mr. French’s column. It was so quiet! Two measured, rational voices speaking through the ink, each backing up their arguments with researchable references and free of bitter, ad hominem jabs. A few bits of pique and tooth grinding to humanize both the defense and the prosecution, but all for the sake of clarifying a complex position.

How civilized! How rare! It’s a shame that the essay was the voice of one man working his careful way through a thicket of legal complexity and not a real-life exchange of ideas in search of a mutually arrived at truth.

Leslie Bell

Davenport, Iowa

A Debate Question

To the Editor:

At the Republican debate I would like to see the moderator ask each of the participants if as president they would pardon Donald Trump if he is convicted of federal crimes.

Walter Ronaghan

Harrison, N.Y.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.