Xochtil Larios, 23, is youth justice coordinator at Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice in Oakland and member of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Commission of Alameda County.

Jacob Jackson, 21, is an organizer for the Youth Justice Coalition in Los Angeles.

Israel Villa, 45, is deputy director of the California Alliance for Youth & Community Justice in the Monterey Bay Area town of Hollister.

Larios was convicted as a teen in a state where juvenile records are sealed. Jackson avoided being funneled down what he calls the school-to-prison pipeline but, after dropping out in 11th grade, was arrested for burglary. After being arrested at age 12 for trespassing, Villa spent much of his adult life in prison, including federal ones.

What follows are edited and condensed versions of their individual stories, shared with journalist Brian Rinker, about how their personal experiences in the juvenile justice system shapes their advocacy of justice reform. This, as their home state of California has transferred control of juvenile incarceration from state prisons, which closed in June 2023, to California counties, hoping that being closer to home will help steer teen and young adult offenders onto a steadier, straighter path.

To a lenient judge, a ‘badass Latina’ was not a ‘bad kid’

Courtesy of Xochtil Larios

Xochtil Larios

When I was a child, my mom, my brother and I sometimes slept in a 2004 Chevrolet Tahoe, our family car, during periods of homelessness. My mom passed it down to me when I was 17. I didn’t have a license at the time but it didn’t matter. The SUV was home.

Even though I slept in a car, I felt like my life was heading in the right direction. I hadn’t gotten into trouble for close to two years. I stopped messing with the gang life. I’d even quit smoking weed. No probation violations. I worked as a swim instructor, a job I loved. I was boxing. I was on track to graduate high school.

Then, one night, I dreamt I went to jail for a very long time. The dream felt real, like a bad omen. I’d been in and out of the juvenile hall in Alameda County since I was 12 for breaking into stores and hanging with gang members on the streets of Hayward. From early on, my family life was unstable. I spent a year in foster care at seven. I grew up in homeless shelters during elementary school. The streets felt more comfortable than home.

That dream scared me. I was done with jail. I told my probation officer I was homeless and needed help, but she told me I didn’t need housing, that I needed to work and save money.

I didn’t know, at the time, that I had rights as a juvenile and could have pressed the issue to gain access to resources. Instead, I thought, ‘I’m a badass Latina, I can take care of myself.’

What happened next still haunts me. I committed a crime. A bad one [whose details I don’t want published]. I didn’t kill anyone but someone got hurt. I was charged with a felony, which was eventually lowered to a misdemeanor. I stayed at Alameda County Juvenile Hall for more than 200 days. It looked like I was headed to juvenile prison.

At some point in jail, I met advocates with the Oakland-based Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice, CURYJ. They encouraged me to get involved in youth leadership and activism. When I get out, they could help me with transportation and housing, they said.

Fortunately, the judge looked at my record, determined I wasn’t a bad kid but that I had a difficult childhood, and gave me a release date.

After I got out, I took CURYJ up on their offer. They even gave me a job as a youth justice coordinator. I joined the Alameda County Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention Commission as its youngest youth commissioner. I also teach a social justice class inside the secure youth treatment facility in Alameda County juvenile hall, so that they know their rights and how to advocate for themselves.

I will never forget my first day showing up at the CURYJ’s office on International Street in Oakland, a notorious boulevard for sex workers. I had stood at that corner when I was 12 and 13 years old.

I had come full circle. I cried. Then, I walked into the office. — Xochtil Larios

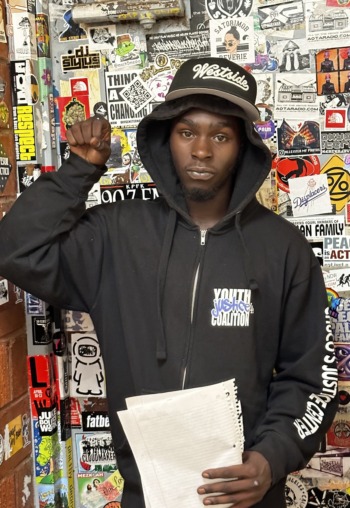

Headed down the ‘school-to-prison pipeline,’ then escaping it

Courtesy of Jacob Jackson

Jacob Jackson

In my second week at Crenshaw High School in South Los Angeles, as I passed two school police officers in the hallway, one of them said to me, ‘We know who you are. We know who you’re going to be.’

‘What does that mean?’ I said.

The officers kept walking.

Growing up in South Los Angeles, I’d seen a lot of Black and brown people arrested and sent to jail, as young as 13. In middle school, I had my run-ins with the school police officers for small stuff, roughhousing and goofing off, but nothing serious.

I thought Crenshaw High School — with its overwhelming population of Black and brown folks — would be more supportive and not criminalize teenage behavior. But after those officers looked at me like I was a suspect, already a criminal, I knew I needed to be careful there, too.

Maybe a month later, I had my second encounter with the school police. A substitute teacher in graphic design, my favorite class, told me to get off the computer. I think he assumed I wasn’t supposed to be in the class and was just there to play video games. I told him I had an individualized education program, allowing special accommodations for my learning disability, and kept working.

But he grabbed my shoulders and tried to yank me out of my seat. I shrugged him off and stayed seated.

“I can have you arrested right now,” he threatened. “I can have charges brought against you.”

He demanded an apology. So, I apologized. But, in my heart, I knew I did nothing wrong.

The next day at school, two police officers handcuffed me, patted me down and read me my rights. ‘We’re going to get the teacher and, then, we will see how your life is gonna play out,’ the police told me.

The substitute teacher made himself very clear: ‘If I decide to press charges right now, you’ll go to jail. I hold your life in my hands.’

I apologized, again. They let me go.

I knew if I stayed there I would turn into what the police and that teacher thought I would: a criminal. After that, I quit school in 11th grade.

My mama, who struggled to pay the bills, while raising us three kids, told me, ‘You’re not gonna sit up in his house and have no money and do nothing and live here all day.’

I needed to get a job. Instead, I got caught breaking into a house.

I got arrested for burglary and put on probation. My mama picked me up that day from the police station and said she’d never do it again.

As I was going to court, my public defender told me it would go better for me if I was enrolled in school. After searching for the right school, I found FREE [Fight for the Revolution that Will Educate and Empower] L.A. High, founded by the Youth Justice Coalition. The teachers made me feel like I was at home. They treated me with respect and supported me.

It was there that I started learning about social justice and community organizing. I learned about using public comment periods in government meetings to get my voice heard. I attended the board of supervisors meetings and went to the state capitol for senate hearings.

I’ve never looked back. I got a job as an organizer, and have worked on various campaigns: ‘College Prep, Not Prison Prep,’ ‘LA for Youth’ and ‘Stop Police Violence.’

I see so many Black youth falling through the cracks, never graduating high school. And those that do, don’t have the resources to attend a university. We need more teachers and staff with similar experiences to us and classes that enforce our culture. That way we can have true support for our academic ambitions. — Jacob Jackson

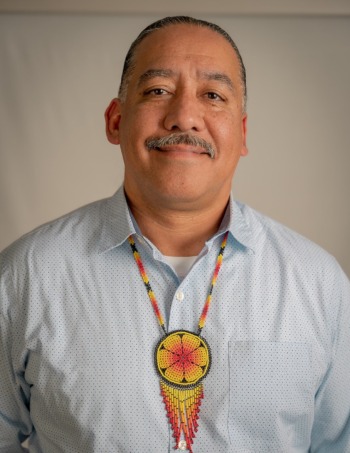

A father who spent half a lifetime in prison has an incarcerated son

Courtesy of Israel Villa

Israel Villa

I attended the meeting where the California Board of State and Community Corrections voted unanimously to shut down two juvenile halls in Los Angeles after a long list of violations.

That vote came too late, though, for Bryan Diaz, who died of a drug overdose at Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall just weeks before.

Being at the meeting triggered me, imagining those 300 kids, mostly Black or Latino, having to piss in towels and corners of their rooms at night because they didn’t have access to bathrooms.

I went through all that same abuse when I was a kid in the 1990s. I spent nearly two decades locked behind bars in state and federal prisons, starting with Monterey County Juvenile Hall, when I was 12, the summer of sixth grade. I’d been arrested for trespassing and put on probation.

I grew up poor in farmworker housing in Salinas, California. I was a smart kid who loved math. But that didn’t matter. Around 11 or 12 I started getting in trouble for spitballs and goofing off in class, eventually leading to suspensions and expulsion. After that, I couldn’t stay out of jail for the life of me, all gang-related charges. I was a violent kid. I’d violate my probation and get sent back to the hall every couple of weeks.

Life was rough. Two of my childhood friends, in separate incidents, were shot and killed in middle school. I caught my first felony at 14 or 15 for robbery with a knife. In 1995, when I was 16 or 17, I was sent to the California Youth Authority for auto theft. I saw more bloodshed in that facility than in any adult prisons I’ve been in.

After the youth authority, I soon caught a new case, assault with a deadly weapon, and was sent to state prison, then, after that, federal prison for conspiracy to distribute methamphetamines.

Being locked up so much, I only saw my first-born son for a total of three years of his entire life. When I was in Santa Clara County Jail, I got word my 16-year-old had been arrested for robbery and assault [though I’m not sure of the charges]. He was sentenced to 28 years with two strikes in adult prison in 2011. I failed him as a father.

Just like hurt people hurt people; healed people also heal people.

During these last nine years I’ve been out of prison, I’ve mentored many juvenile justice-involved young people, received the Pacific Juvenile Defender Center’s Youth Advocate of the Year award in 2020 and served on committees and workgroups at the Board of State and Community Corrections.

I also reconnected to my Indigenous roots. I burn sage and cedar as medicine to help rid me of negative energies and emotions. It helps me to stay grounded in my values of love and village culture. I especially need my medicine as I fight for the youth stuck in a system that I see as abusive, neglectful and racist.

I am far from being healed, but, today, I know that I am walking the right path. — Israel Villa

***

Brian Rinker is a Pennsylvania-based journalist who covers public health, child welfare, digital health, startups and venture capital. He reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.