In 19thcentury Boston, a boot-maker named John Augustus, an activist in the temperance movement, convinced judges that rather than sentence offenders to the house of correction, he would try to rehabilitate them. In an interview with Gene Denby, host of NPR’s Code Switch, Vinvent Schiraldi, author of the new book, Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom (New Press, 2023), said that to the chagrin of cops and constables, Augustus did this several thousand times. So he is “considered the father of probation” (https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1197954050).

Augustus’ activism didn’t sit well with the police who stood to make money if people were convicted. “If the person wasn’t” convicted, Schiraldo pointed out, “then it was viewed as a waste of the court’s time, so the police officers didn’t get paid for it. … What they started doing was to put all of the people Augustus wanted to release at the end of the docket,” which cost Augustus time and money. Eventually, Augustus’ business failed and he died destitute.

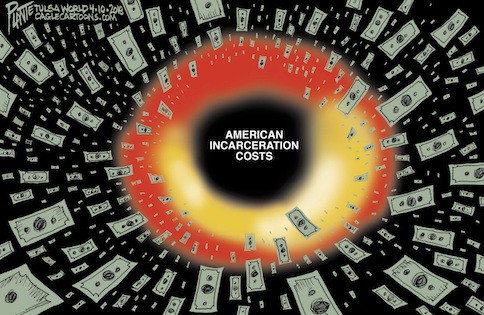

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with nearly two million people in American state or federal prisons and local jails. And, there are nearly four million more who are on probation and parole. Over the years, much as been written about mass incarceration, private prisons, and the horrendous conditions incarcerated men, women and juveniles face every day. However, there hasn’t been much coverage of the probation and parole system, where private corporations and often cash-strapped municipalities benefit from fees and fines that are levied against former prisoners and those on probation. Failure to pay can land a parolee back in prison.

“As the number of cases processed by this country’s police and courts and supervised by probation and parole has exploded during the era of mass supervision, policymakers have been reluctant to fully finance their punitive zeal,” Vincent Schiraldi writes in Mass Supervision.

This has contributed to growing fees charged to justice-involved people for the costs of court processing, defense, prosecution, jail, and probation and parole supervision, among other things. ‘Offender’ or ‘user’ fees help support the system of punishment that has mushroomed over the last four decades. They can also turn a profit for cash-strapped communities, supporting general governmental operations that have grown dependent on extracting fees from poor defendants to support functions unrelated to the justice system.”

Schiraldi, who spent more than forty years in nonprofits, academia and running several correctional and probation departments, is the founder of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice and the Justice Policy Institute. He currently is the secretary of the Department of Juvenile Services for Maryland. “Paying to be on probation has flourished in small towns throughout the South (where private companies often receive the proceeds) as well as in big cities (where more often the recipients are government probation or parole departments),” he writes.

As elected officials campaign on tax cuts simultaneous with ‘tough-on-crime’ measures—the latter fueling a system’s growth, the former starving it of resources—something has to give. Probation and parole find themselves caught in the middle, providing bare-bones supervision for an oft-disdained group of people who have broken the law, while trying to avoid the risk that reoffending poses for their elected official bosses. Fees and privatization are a near-inevitable outgrowth of the colliding forces of budget tightening and supervision expansion.

Parole is the other side of incarceration. It is the release of a prisoner temporarily or permanently before the completion of a sentence, on the promise that good behavior will follow. Schiraldi explained that idea of parole originated in Australia “when it was still a British penal colony.” Prison conditions “were so bad that the person overseeing them decided to try something different, like releasing some of those prisoners with help and supervision from volunteers.” A fellow named Zebulon Brockway, who ran the Elmira prison in New York, brought that idea to the U.S.

Fast forward to the Nixon and Reagan administration and the war on drugs/crime/Black people, which results in mass incarceration. “[I]n ’72, we have about the same incarceration rate as our Western allies. By 2008, we have an incarceration rate that is five, seven, 10 times our Western allies,” Schiraldi tells Code Switch. Lock-em-up is the name of the game and the idea of rehabilitation becomes a non-starter.

Mass incarceration ultimately leads to mass supervision. With budgets being tight, the work of managing people’s probation and their parole is now being outsourced to private contractors. The charging of fees and fines emerge as a way to stretch local budgets.

Schiraldi tells NPR’s Demby: “But then somebody … thinks, … if there’s fees involved here, I can make money off of this. And so they start to go to small communities that are – … paying for a probation department” and convince them that these companies can “supervise all your people, and we’ll get the money out of them.

“And you know what else? We’ll kick some money back into the public coffers. We’ll throw you a profit, and we’ll make a profit, ourselves. And we’ll do it all on the backs of poor people. And so when that starts to happen, now hundreds of thousands of people go on private probation.”

Because people can often not afford the fines, they are reincarcerated. According to Schiraldi, one out of four people “enter for technical, noncriminal violations of probation or parole.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.