The wooded slopes of the Ettersberg stand in the center of Germany, a few miles north of Weimar. Beginning in the eighteenth century, the area served as the playground of dukes, who went there for hunting, and later as the preserve of poets, who traversed its rugged hills while contemplating the wonders of nature. No less an eminence than Goethe, the greatest of all German poets, traveled often to the forests of the Ettersberg, and over the years he grew particularly fond of one large oak tree near a clearing with expansive views of the countryside. On a bright autumn morning in 1827, a banquet-like breakfast was laid out in the shade of this grand oak. Leaning back against its regal trunk, Goethe feasted on roast partridges, drank wine from a gold cup, and gazed out at the rolling landscape. “Here,” he declared, “a person feels great and free…the way he should always be.”

After Goethe’s death, as a cult of reverence formed around him as the standard-bearer of both German genius and European humanism, the legend of his favorite local tree evidently survived—all the way down to one summer day more than a century later. That day in 1937, a group of prisoners was led into the same high forests of the Ettersberg, stopping at a limestone ridge just six miles north of Weimar. Under harsh conditions and with minimal equipment, these men cleared away the trees to make room for a concentration camp.

As the prisoners labored day after day, building their own future prison, their guards identified one particular oak that would not be felled. This oak, it was determined, must be the mythic Goethe’s oak. And so the anointed tree was left standing, and in the years that followed, the concentration camp of Buchenwald rose up around it on all sides.

To the inmates of Buchenwald, the tree took on different meanings, as an incongruous vestige of the older Germany, a potent reminder of European culture’s utopian promise.

To the Nazis who created Buchenwald, Goethe’s oak represented a tangible link to German history at its most illustrious, a history that proved the German people’s cultural superiority while pointing toward the thousand-year empire of their dreams. To the inmates of Buchenwald, the tree took on different meanings, as an incongruous vestige of the older Germany, a potent reminder of European culture’s utopian promise, and a silent witness to unspeakable crime. Over the course of the next seven years, the men and women in the surrounding camp were enslaved, murdered, and worked to death. Some of Hitler’s victims, according to one account, were hanged from the branches of Goethe’s tree. The oak itself eventually stopped producing leaves. In one photograph taken by a prisoner with a stolen camera, its branches appear bare and skeletal, reaching up into the empty sky.

Some prisoners linked the tree’s fate with that of Nazi Germany, which by the summer of 1944 was careening toward its own downfall. At approximately noon on August 24, 1944, 129 American aircraft converged over the camp and rained down their fury, dropping one thousand bombs and incendiaries and successfully destroying a munitions factory attached to the Buchenwald complex. That factory had been their prime target, but there were additional casualties: one hundred SS men, nearly four hundred camp inmates—and the old oak tree, which had been scorched by flames. The camp leadership had it felled and sawed for firewood, but one resourceful inmate named Bruno Apitz—a Communist prisoner who had survived in the camp since the year it opened—managed to smuggle back to his barracks an entire block of the tree’s heartwood. With his fellow prisoners standing guard, Apitz risked his life to carve from the wood a bas-relief in the form of a death mask. He called it Das letzte Gesicht (The Last Face).

____________________________________

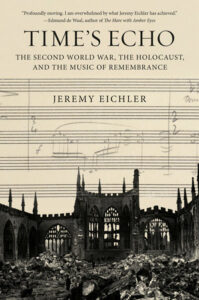

Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance by Jeremy Eichler has been shortlisted for the 2023 Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction.

____________________________________

This simple, rough-hewn sculpture—later smuggled from the camp and now owned by the German Historical Museum—individualizes the enormity of Nazi violence through the prism of a single face. It can be thought of as among the early memorials to the Second World War and to the events that, years later, would be called the Shoah or the Holocaust. The grief that lines this last face is grief for all that died at Buchenwald: for the inmates but also perhaps for what the oak represented—that is, the grand European promise of a high culture of poetry, music, and literature, and the very idea of a humanism that might one day unite all people as equals.

While Apitz was at work, chisel in hand, another memorial inspired by the heartwood of German culture was taking shape some three hundred miles away. In Richard Strauss’s villa in the mountain-ringed town of Garmisch, the eighty-year-old composer wrote out two short poems by Goethe, the first one opening with the lines “Niemand wird sich selber kennen, / Sich von seinem Selbst-Ich trennen” (No one will ever know himself / Separate himself from his inner being). The second poem begins “What happens in the world / No one actually understands.” These reflections on the limits of self-knowledge must have resonated with Strauss, a composer who had spectacularly failed to understand his own actions and the world in which he found himself in 1933. During the years of the Third Reich, he had severely misjudged his surroundings, remained in Germany, and forever tainted his reputation by working with the Nazis in the area of cultural policy. He also witnessed the suffering of his Jewish family members (which included his daughter-in-law and his grandchildren) and the wartime destruction of his true spiritual homes, the opera houses of Munich, Dresden, and Vienna.

Now, in August 1944, the world-weary Strauss began work on a choral setting of the first of the Goethe poems, but never completed it. Instead, he swept the musical ideas, which still bore the ghosted impressions of Goethe’s language, into a new composition—a spiraling work of mournful grandeur titled Metamorphosen. It would become an elegy to German culture, a death mask in sound, and one of Strauss’s most moving musical utterances, speaking forcefully to the emotions while sealing its secrets behind the music’s veil of wordless beauty. On the score’s final page, Strauss inlaid a quotation from the funeral march of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, and below it he inscribed a single lapidary phrase: “IN MEMORIAM!”

Unlike the artist of the sculpture carved at Buchenwald, however, Strauss did not specify what precisely his music was attempting to remember. To this day, whenever the piece is performed, the question reappears. It is no longer his to answer.

__________________________________

From Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance by Jeremy Eichler. Copyright © 2023. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.