Part of the Series

Progressive Picks

“The precariat is not the equivalent of what we used to call the working class,” National Book Critics Circle award recipient Eula Biss writes in the introduction to American Precariat: Parables of Exclusion. “More common now is gig work, with no set hours, no potential for advancement, work done through the interface of an app by workers who don’t know the people for whom they’re working.”

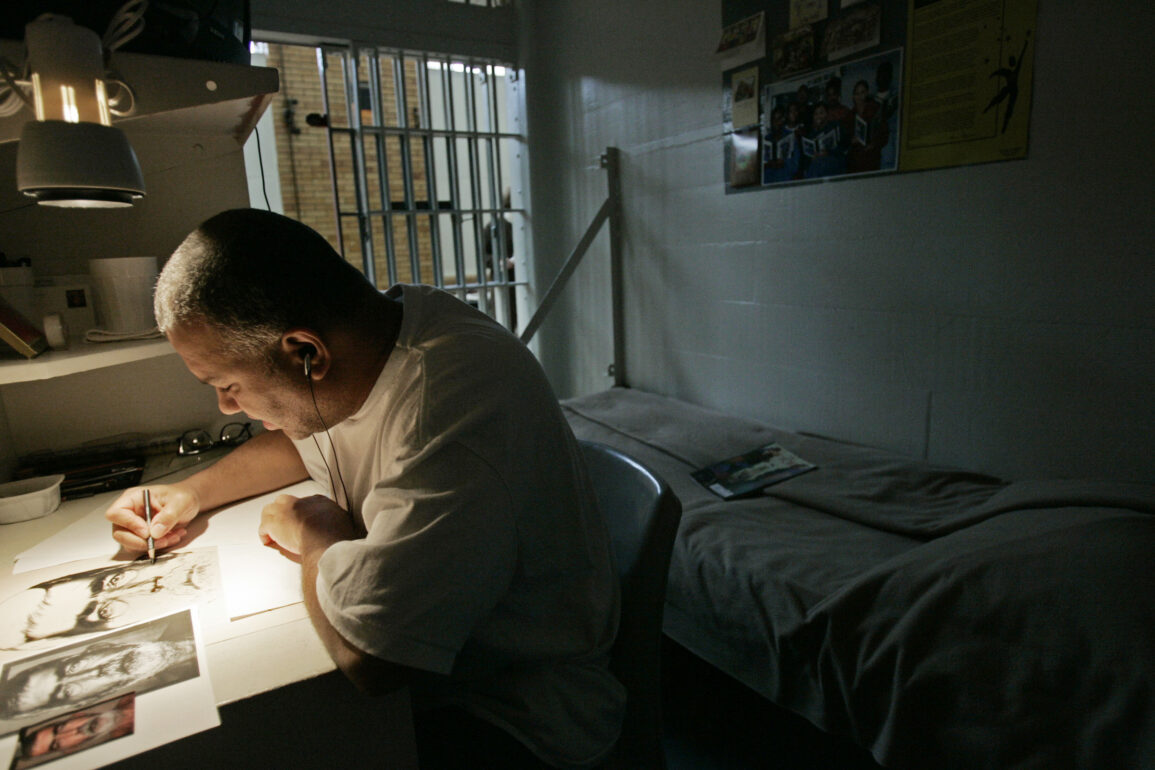

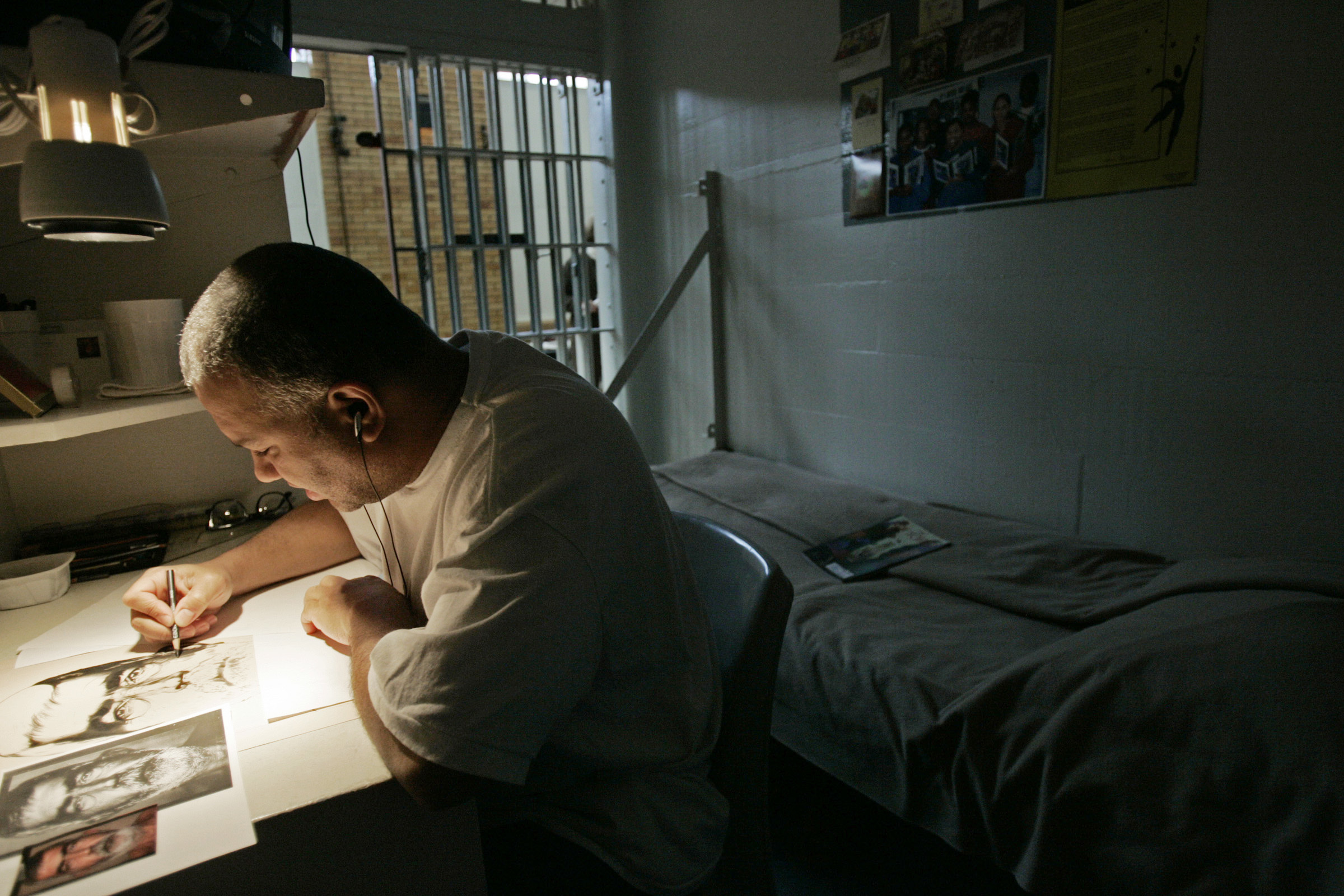

But the phenomenon of economic and social precarity is also more than this, and American Precariat, a book edited by 12 men incarcerated in Minnesota’s Faribault, Moose Lake and Stillwater prisons, explores the ways that U.S. residents have been pushed to the edge by crushing student loan debt, homelessness, racism, mental illness, physical disability, anti-trans bigotry, workplace instability and undocumented immigration status.

It’s a powerful, incisive and provocative collection, compiled over four years that began before COVID-19 and extended well into the worst of the pandemic.

“COVID-19 did just what time in these places does — changes and complicates things further,” PEN Prison Writing Contest winner and editor Zeke Caligiuri writes in the book’s foreword. “There were expected and unexpected transfers, incongruent security priorities and lockdowns that made it impossible for our cohort to meet.… We had to depend on individual institutions to relay memos and manuscripts.”

Still, the men persevered, selecting 15 essays for inclusion in the anthology and then editing and discussing them.

In some ways, it was a familiar process since each editor had participated in editorial boards that grew out of classes sponsored by the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop (MPWW), a 13-year-old nonprofit that brings educational programming into the state’s 10 adult prisons.

American Precariat is their first full-length release, published through a collaboration between the MPWW and Coffee House Press. The editors are understandably proud of it.

“As members of the ultimate precariat, we brought a unique set of skills into the process,” editor Kennedy Amenya Gisege writes on the MPWW website. “I ask every person who reads this [book] to advocate for one person that is suffering, who is being oppressed or ignored.”

MPWW’s founder and Artistic Director Jennifer Bowen spoke to Truthout’s Eleanor J. Bader about MPWW’s work and the process of bringing the collection to fruition.

Eleanor J. Bader: Let’s start by going back to 2011. How and why did you start MPWW?

Jennifer Bowen: I was initially a volunteer teacher at Lino Lakes Prison. There were six men in my first class, and it was deeper and richer than any class I’d taught before. It felt too meaningful not to continue.

Part of this was where I live. The Twin Cities are full of artists and writers and there is robust state funding for the arts. It just made sense that writers would go into the prisons, especially since there’s a staggering amount of interest among incarcerated folks in having classes available. The incarcerated want to learn and many people on the outside want to teach. After my initial experience, I returned to the prison classroom and recruited a few other writers to do likewise. Things mushroomed, and while I had not planned to create a nonprofit, after a few years of recruiting teachers and coordinating classes, it was clear that we needed a structure to hold this. This became MPWW.

How has the program grown and changed since 2011?

We now have between 25 and 30 teachers who go into the state’s adult prisons. All are paid. We also have a cohort of 50 volunteer mentors from all over the country who receive monthly packets from incarcerated writers. The mentors offer feedback and work with the individual for up to four years.

What happens after four years?

The four years is admittedly an arbitrary cutoff and we’re flexible. People often want to stay in touch after the formal mentor-mentee relationship ends, and can, but we feel that it is important to introduce new mentors every so often. Writers, whether they’re poets, novelists, essayists or playwrights, benefit from additional perspectives. After all, there’s only so much one writer can teach!

American Precariat is wonderful, but are there other MPWW achievements that you’re proud of?

The most exciting and successful thing we’ve been part of is supporting and growing writers’ collectives. There was one at Stillwater when I started teaching there that had been created by the men themselves. They knew they needed a sturdy arts community, so they organized one.

Something Zeke Caligiuri told me is true: In any prison, the artists find each other.

As MPWW expanded, we worked closely with the collective at Stillwater and they helped us create a flourishing creative space. At their urging, we brought writers from the outside in for a reading series and we advocated for the creation of collectives in other facilities. We learned that establishing and maintaining collectives provides continuity, especially when people are moved from one prison to another.

How large are these collectives?

It varies. In Faribault and Moose Lake, there are about 20 collective members. Pre-COVID, the Faribault group was larger and folks were forming a second collective so that the operation would be more manageable. That never happened due to the pandemic.

With the exception of the state’s maximum-security prison, the collectives are now springing back to life in minimum- and medium-security facilities.

Even before American Precariat was developed, MPWW helped many individual writers publish their work. Tell me about this.

People connected to MPWW have published memoirs, poetry and essays. Zeke Caligiuri published This Is Where I Am, and Christopher Fausto Cabrera, with Alec Soth, recently published The Parameters of Our Cage. MPWW participants have had work accepted by The Nation and by Poetry Magazine, among other journals, and are constantly submitting to contests and competitions. Each year our students win PEN prizes and justice awards. In addition, we publish an annual journal that features work from students who participate in our classes. Writers’ collectives rotate responsibility for editing and arranging each year’s publication.

Let’s talk about American Precariat. It must have been really difficult to pull the collection together.

In recent years, the literary world started to recognize that there were writers in prison, and several anthologies about prison conditions were released, but they contained writing by non-impacted folks. It was both maddening and incredible to see this. At the same time, we knew that incarcerated people could write — and write well — about more than prison life. They could write about parenting. Or cooking. Or grief. Or about writing and creativity.

When we decided to do a book, we spoke to Chris Fischbach at Coffee House Press. He advised us to ask the collectives what they wanted their book to do. The men said that they wanted to break silences and shame. They then put out a call for submissions on social media and in magazines like Poets & Writers, asking for essays that addressed precarity.

The book was in the making for four years.

Why precarity?

The editors wanted a book that would reveal fractures in society that are usually not talked about. Furthermore, they hoped that a book articulating silent precarity might offer a little bit of healing. This reflected our understanding that speaking about unacknowledged issues can be helpful to people who are feeling isolated or alone.

Did lots of people respond to the call for submissions?

We received about 500 submissions and the editors read all of them. But once COVID-19 hit, this became a nightmare because MPWW staff were not allowed to go into the prisons. This meant we had to pause the project. When the world opened back up in 2021, I went back into Faribault. We eventually reengaged collective members from three prisons, and after reviewing the essays, we concluded that there were certain topics we absolutely needed to include. Despite the volume of submissions, we had to solicit pieces about trans identity and mental illness. It felt irresponsible not to include these topics in a book about precarity.

It was really challenging.

We also had to grapple with the fact that not every essay could be written from inside the issue. For example, someone who is currently unhoused is less likely to be able to write their own story than someone who has shelter. The same is true of people experiencing a mental health crisis. We wanted marginalized individuals to tell their own stories, but recognized that this was not always possible.

Each essay is followed by excerpts from conversations between the editors. Why did they want readers to get a taste of their discussions and debates?

We think the outside world will be surprised by the humor, respect, intellect and camaraderie that the conversations reveal. We felt that it is important to showcase their rich and brilliant thought processes. We also love how they highlight what reading can engender.

Narrowing it down to 15 essays must have been grueling. Did people come to consensus or were there contentious issues?

We did not have consensus on everything and some editors hate essays that other editors love. But we compromised.

There was also struggle over the fact that one essay can’t possibly represent an entire spectrum of concerns or an entire population. We wanted to avoid stereotypes and oversimplification. Should we reject an essay because a homeless person is depicted as an addict? What about one in which a mentally ill person causes harm?

Some of our debates were really heated and we finally had to accept that it was impossible to represent every perspective.

So yes, it was a difficult process but, overall, everyone is proud of the final product. Editors have given me a list of people they want to receive American Precariat, teachers and writers they know who they hope will review the book or use it in their classrooms.

We’re all crossing our fingers that the book is well-received.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.