In 2005, as protests broke out across France after two teenagers died while hiding to avoid police interrogation in the Parisian banlieue Clichy-sous-Bois, Bourouissa embarked on what would become known as his breakthrough photographic series, ‘Périphérique’ (2005–2008).

Each image features Bourouissa’s friends and acquaintances restaging scenes from French history paintings within the Parisian suburbs where they grew up, and where civil unrest broke out in 2005 in response to the policing of mostly migrant youths in disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods.

Mohamed Bourouissa, La République (2006). C-print. 137 x 165 cm. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Archives Mennour.

La république (2006), for instance, re-enacts Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting Liberty Leading the People with young men enveloped by tower blocks. It’s a bold appropriation of the French Revolution’s legacy to make visible another claim for equality, this time expressed by those whom France had colonised.

‘Périphérique’ expresses a core inquiry in Bourouissa’s practice: how the carceral state, which relies on punishment and surveillance, extends from the colonial history that defines France as much as its republican revolution that helped shape the international nation-state system today. Projects that followed include Temps mort (2008–2009), a moving-image work composed of videos and texts exchanged between the artist and his jailed friend, and the video Nasser (2015), where Bourouissa’s uncle struggles to read his court judgment for violent robbery after getting into a fight for food.

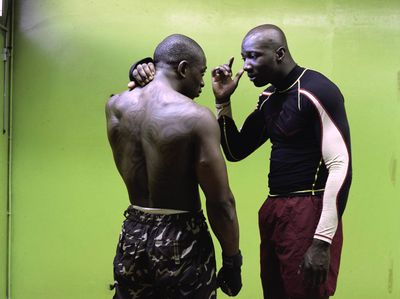

Mohamed Bourouissa, ‘Shoplifters’ series (2014–2015). Exhibition view: HARa!!!!!!hAaaRAAAAA!!!!!hHAaA!!!, Goldsmiths CCA, London (21 May–1 August 2021). © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Mark Blower.

But while Bourouissa’s work is anchored to the post-colonial experience of the French carceral state, his practice extends to other contexts.

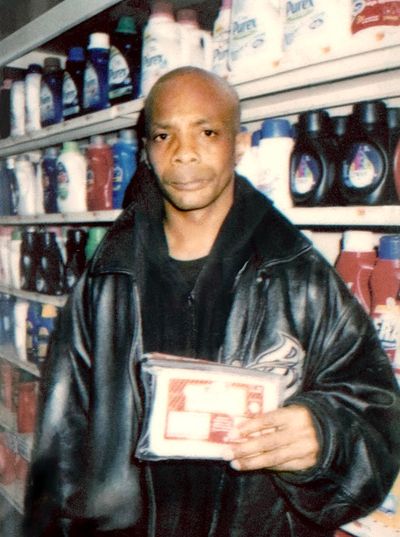

The installation Shoplifters (2014), for instance, presents photographs of photographs that the artist encountered on a wall in a New York grocery store. Taken by the store manager, each image shows a shoplifter holding the things they stole, like laundry detergent and bread, magnifying the systemic inequality driving the actions on either side of the camera.

Mohamed Bourouissa, La fenêtre (2005). C-print. 90 x 120 cm. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Archives Mennour.

Shoplifters is among the more challenging projects Bourouissa has worked on, he says. As a project, it captures the compositional logic he defines in La fenêtre (2005), which he pinpoints as the first photo that he consciously composed to encapsulate the tension between context, reality, and an artistic viewpoint.

That triangulation expands in the two-channel video installation Horse Day (2014–2015), which focuses on the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club in North Philadelphia. Marking the first time the artist embedded himself in another community, Bourouissa lived among the Fletcher Street community for months, eventually proposing to organise a horse pageant that is shown in the resulting film.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Horse Day (2014–2015). Video diptych (colour, sound). 13 min, 32 sec. Exhibition view: HARa!!!!!!hAaaRAAAAA!!!!!hHAaA!!!, Goldsmiths CCA, London (21 May–1 August 2021). © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Mark Blower.

More recently, Bourouissa’s gaze has returned to France to address the police state once more. For his latest exhibition at Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary, and Outsider Art, Strange Attractor (29 September 2023–21 January 2024), Bourouissa presents new sculptures that isolate bodily contact points created during police searches.

He also is showing a new single-person play, Quartier de femmes, created through workshops with inmates at a women’s detention centre in Lille, and co-produced by T2G Théâtre de Gennevilliers, with whom Bourouissa staged what Radio France described as ‘an artistic fair in the suburbs in the midst of riots’ in July 2023, and the Festival d’Automne à Paris in partnership with LaM, the Penitentiary Centre of Lille Loos Sequedin, and Unité Sa.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Quartier de Femmes (2022) (still). © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris.

In this conversation, Bourouissa discusses these latest works in relation to previous projects. He mentions Brutal Family Roots, an installation commissioned for the 2020 Biennale of Sydney, which turns the electrical activity of acacia shrubs into sound, as well as The Whispering of Ghosts (2018–2020), a short film tracking a community garden that Bourouissa developed for the 2018 Liverpool Biennial.

The Whispering of Ghosts shows footage of Bourouissa talking about gardening as a form of occupational therapy with Bourlem Mohamed, a patient at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Bourouissa’s Algerian hometown Blida, where revolutionary psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon once practised. These ideas infused the artist’s installation in Liverpool, creating a link between Algeria and the British port city that expanded in the garden itself, which was populated by plants that connected to the migrant communities living in the area where it was developed.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Resilience Garden (2018). Mixed media, variable sizes. Exhibition view: Beautiful world, where are you?, 10th Liverpool Biennial (4 July–28 October 2018). © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP. Courtesy the artist.

For Bourouissa, plants, bodies, and animals have all been subject to the legacies of colonialism—a violent triangulation that Bourouissa highlights in this discussion, which took place shortly after a French teenager of Algerian and Moroccan descent was shot dead by a policeman in Paris, sparking furious protests across France and beyond.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Idriss (2023). Aluminium cast. 49 x 40 x 30 cm. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Archives Mennour.

SBYour photographic series ‘Péripherique’ commenced around the time of the French riots in 2005; both responded to the policing of migrant communities in Paris. Works like Temps mort that followed continued to interrogate the police state in France, while more recent projects reached out to communities elsewhere, as with the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club in the United States.

With that in mind, your show in Lille seems to return to the core of your practice, looking at the policing of migrant bodies in France. This feels timely given the recent killing of an Algerian teenager by police in Paris in June 2023.

MBTotally. My work is very much about how a structural power can demolish the immigrant body over generations with a sustained level of violence. I am still working through this question and trying to understand the root of this violence through my practice.

What we see from these events today relates to the mechanisms of empire and the history of colonisation, which is the source and root form of domination. Nothing about this historical violence has been resolved. For example, we have one section of the police in France that was created during the Algerian War [1954–1962], which shows how the mechanisms of the structural state are rooted in colonisation and continue to operate.

To clarify these roots is an obsession that I have kept exploring since my series ‘Périphérique’, and now, with new sculptures I am showing in Lille looking at how the body is controlled.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Lou-Adriana Bouziouane in Quartier de Femmes (2022). © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris.

SBYou are also presenting a new one-person theatre piece, Quartier de femmes, which looks at the carceral state from a woman’s perspective. Could you talk about that?

MBI developed the theatre piece with inmates at a detention centre for women in Lille. Since there is a tendency to only associate the prison state with men, learning more about the female perspective on prison was a really interesting experience for me.

I worked with Zazon Castro, a writer, artist, and actress, and we spent almost two months working with inmates there. At first, the idea was to write the script with a woman prisoner, but it soon became clear that the inmates didn’t want to write anything. They just wanted the space to express themselves and find time to meet again.

So we recorded what they said, and they gave us so many anecdotes, stories, and thoughts to turn into a script about a woman who goes to prison where she encounters other women. A single actress performs every character, all of whom are inspired by the experiences we had in this women’s prison.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Quartier de Femmes (2022) (still). © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris.

The piece takes inspiration from a reading of the ancient Greek tragedy Antigone, which presents one woman’s dilemma when it comes to navigating the lines between morality and justice. Of course, Quartier de femmes moved quite far from Antigone in the end, but I kept some sources from the original play.

Through the performance, we see how one woman’s experience in prison changes her thoughts and feelings about her personal history. She reflects on why she’s there, and how she is revealing herself—not in relation to the institution of prison but rather with other human beings.

In complicated situations, the laugh can exorcise the situation, breaking down the wall between the individual and the public.

Rather than make something dramatic, I decided to play with ideas of stand-up comedy because comedy is a form of resistance to the paternalistic feeling that people can have when it comes to the lives of those less fortunate. In complicated situations, the laugh can exorcise the situation, breaking down the wall between the individual and the public.

Mohamed Bourouissa, 12.11.12 (‘Shoplifters’ series) (2014–2015). Inkjet print. 32 x 24 cm. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris.

SBIs it fair to say that this turn to comedy marks a shift in how you are expressing the violence of the carceral state in your work?

Take your project Shoplifters, which presents found photographs of people caught shoplifting. This violent and humourless intervention raises a lot of questions in terms of consent and objectification, which Quartier de femmes mediates by condensing real-world experiences into a composite portrayal of non-fiction.

MBBecause I didn’t know the people in the pictures, the most complicated thing about Shoplifters was whether I had a role or a right to take those images and work with them in the first place.

It’s quite different with Quartier de femmes because this project engages with the people involved. It was very clear when we presented the project to the women prisoners exactly what I wanted to do, and even the casting of the actors involved the women who were being represented.

That’s why Quartier de femmes was ethically easier for me. I had the opportunity to clarify the project and found ways to portray people I met so they felt that the material was not too far from what they gave us, while maintaining their anonymity.

Mohamed Bourouissa, ‘Shoplifters’ series (2014–2015). Exhibition view: HARa!!!!!!hAaaRAAAAA!!!!!hHAaA!!!, Goldsmiths CCA, London (21 May–1 August 2021). © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Mark Blower.

When it came to Shoplifters, it was about the balance between showing those images and not showing them. I decided that it was more important to show them, even if I knew the work could be problematic. When you see the pictures, you feel uncomfortable. You can say this photographer did not have the right to take the pictures, or that I, as the artist, have no right to use them. But at the same time, you are looking at these images. You are part of the surveillance structure.

That project was also about who took those pictures, which, in this case, was the store manager. For me, that was important to highlight because it speaks to a form of structural violence where people are caught stealing in supermarkets, which are materially abundant, because of the scarcity they are subjected to within society. It’s about this idea of being part of this social structure where no one really feels safe.

Mohamed Bourouissa, The Whispering of Ghosts (2018) (still). Video, colour, and sound. 13 min, 15 sec. Co-commissioned by FACT and Liverpool Biennial. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris.

SBAs an artist, you tend to take complex positions. This comes across in The Whispering of Ghosts, which includes footage of local white men in Toxteth, Liverpool. They ask you why you’re not working on a community garden in Algeria since the Muslims in Toxteth, according to them, are fine; while in Algeria, Bourlem Mohamed likewise asks why you don’t come home.

Across your work, you take on the role of insider and outsider at once, drawing connections between contexts through your own experiences as an Algerian-born French citizen with an international art career. How do you make sense of this embodied intersection?

MBFor me, you cannot understand the opposition between where you come from and where you are if you do not understand the idea of globalisation and its artefacts. We can’t compare the history of America with what is going on in Liverpool, but we can see similarities in the mechanisms of globalisation through both contexts.

The people from Philadelphia and Liverpool that I met had different struggles. They did not share the same stories as they were from different parts of the world. But the mechanisms of migration are related due to the countries that colonised them, so there are structural similarities.

This helped me understand my own position in France with my Algerian background. Algeria was very involved with movements in post-colonisation and decolonisation within the context of pan-Africanism and the Non-Aligned Movement. At the time, global relationships developed between communities, activists, thinkers, and artists, and different ideas emerged to deconstruct polarities around power.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Horse Day (2014–2015) (still). Video diptych (colour, sound). 13 min, 32 sec. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris.

Connections like these can help you find your bearings because as an outsider you can’t only understand things from your own perspective, nor become part of a community by spending time in a place. Now, when I go to Philadelphia, I feel more like a part of the community, but in the beginning, it was hard.

I cannot understand what it’s like to be a Black man in America based on my experiences as an Algerian in France. Some feelings are different, but comparing experiences can help clarify and define who you are and where you stand.

For me, understanding what it means to be part of the community was clearer in Philadelphia and Liverpool than in France, where there is this opposition between community and assimilation. Through these experiences, I try to open up definitions of community that help clarify my position.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Island (2015). Film (black-and-white drawings, sound). 11 min, 47 sec. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Archives Mennour.

SBThinking about how experiences of connection across contexts inform your work, could you talk about your 2015 short film Island, which you are also showing in Lille? This seems like an outlier in your practice when compared to previous works.

MBIsland is a critique of the 1964 Russian film Soy Cuba, directed by Mikhail Kalatozov, and how people see and feel about this film today. The film is composed of about 200 drawings that reconstruct interviews conducted by a Cuban teacher and scriptwriter I met through Skype, Estrella Diáz, who recorded interviews she conducted in person with people in Cuba.

I think Island is very particular and different from my other works. It’s more related to Temps mort, a video created out of the impossibility of my going directly into prison to shoot the work, so I used a cell phone and the internet in a subversive way to get into a place I could not enter.

The situation for Soy Cuba was quite similar. I was invited to participate in the Havana Biennial, but they didn’t have the money to pay for me to go to Cuba, so I said, ‘Let’s try and use the internet to make something.’

Mohamed Bourouissa, Island (2015) (still). Film (black-and-white drawings, sound). 11 min, 47 sec. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Archives Mennour.

I came up with the idea of Island because I didn’t know anything about Cuba, only Soy Cuba. It’s a big cinematic reference—so many directors have been inspired by it. So I applied the same protocol as I did with Temps mort, and that’s how the adventure started. I connected with Diáz online, who interviewed her students about the film, as well as the film’s scriptwriter and one of the actresses, and I created the drawings to illustrate these conversations.

It was quite interesting. When Diáz asked the scriptwriter what he thought about Soy Cuba, he said the film did not really represent what Cuba is because it was made by a Russian director applying his perspective and politics to the film. Despite being a big cinematic reference, it was not a representation of Cuba so much as an idea and ideology of it.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Idriss (2023). Aluminium cast. 49 x 40 x 30 cm. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Archives Mennour.

SBHow does this distance between an idea and its reality relate to the new sculptures you have created based on contact points in a police stop and search?

MBThe sculptures are related to the contact point created when somebody catches or touches you, so they show hands touching another person’s body. When I made the sculptures, I was thinking about turning the body into a dangerous object. Because that’s what happens when the police catch you—you are not a subject anymore.

For me, this is all about the relationship between the body and the social structure it finds itself within.

The sculptures think about the body in a way that expands on how I tried to understand how we see plants as objects rather than subjects in Brutal Family Roots, which looks at how we categorise humans, plants, and animals.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Brutal Family Roots (2020). Exhibition view: HARa!!!!!!hAaaRAAAAA!!!!!hHAaA!!!, Goldsmiths CCA, London (21 May–1 August 2021). © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Mark Blower.

Brutal Family Roots expressed a very philosophical, conceptual, and deep view of this modernity we are living in, where categorisations that developed during colonisation have shaped the globalisation we are experiencing now. The thought came from the film I made with Bourlem Mohamed, The Whispering of Ghosts, as part of my Liverpool Biennial project, Resilience Garden.

Mohamed is a patient at the hospital where Frantz Fanon worked for a few years before Algeria’s independence, which helped turn Fanon into one of the most important philosophers of post-colonialism.

Mohamed Bourouissa, The Whispering of Ghosts (2018–2020). Exhibition view: Beautiful world, where are you?, 10th Liverpool Biennial (4 July–28 October 2018). © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP. Courtesy the artist.

In The Whispering of Ghosts, I talk with Mohamed about his experience of building a garden and his relationship with plants, which were very active in his life. I learned a lot from these exchanges and started to develop this relationship with plants the more I tried to understand Mohamed’s connection to them. I tried to reveal this experience through the film and the garden I developed in Liverpool.

Of course, this idea of plants being active in our lives is a very basic thought, like when you breathe. For me, this is all about the relationship between the body and the social structure it finds itself within.

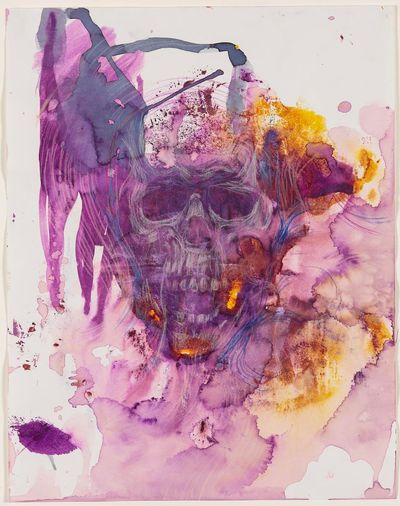

Mohamed Bourouissa, Untitled (2022–2023). Ink, watercolour, and coloured pencil on paper. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Nicolas DeWitte.

SBListening to you talk about Bourlem Mohamed and his relationship with plants made me think about the handling of plants, which connects to your sculptures that zoom in on contact points between bodies.

This tactility comes back to the activation of plant sounds in Brutal Family Roots, which effectively thinks about the police state as an all-encompassing sensory as much as systemic experience. How do your new watercolours relate to this?

MBThe watercolours are related to this feeling of improvisation that I tried to express through Brutal Family Roots. When you make sound, you feel frequencies and waves, which is similar to how watercolour mixes on paper. To me, this relates to how humans, plants, and animals have become categorised.

That’s why I started to make watercolours, which mixes these reflections of how the body starts to become an object when the police apprehend it, and the sensation of how this relationship affects the body. It’s a thought I’m still developing through my work.

SBIt’s about enmeshment, right?

MBExactly.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Pierrot (2023). Aluminium cast. 40 x 54 x 34 cm. © Mohamed Bourouissa, Adagp, Paris, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Archives Mennour.

SBThis circles back to your new sculptures and the intimacy in these contact points. There’s a kind of High Renaissance homoeroticism, which has been a reference for you.

MBYes, there is a very sexual aspect in the representation of masculinity and how this can be a form of domination and mediation that brings these concepts together.

SBThat tension recalls La fenêtre, from the ‘Périphérique’ series: a photo of two boxers in deep discussion, which you have described as the first image you made intending to capture the tension between context, reality, and an artistic point of view. How has this tension evolved in your work?

MBI just try to create forms of experience. I like to work in a way that relates to the methodology of a scientist, by devising protocols through which I can explore different possibilities and see what happens. For example, with La fenêtre, I asserted one protocol, the idea of the frame, and through that, I tried to create a space of possibility.

My approach changes, so my work can seem very disparate. Sometimes, I just try to find the best way to mediate the art and the context, and through that, the form emerges. Sometimes, the form that comes is just relevant to the situation.

But at the same time, the forms and textures change a lot because I don’t want to have my side or take a single position. It’s the same with crystals: when crystals form from different minerals and elements, like gas, air, and oxidation, their colour and shape change. —[O]

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.