When people think of the American criminal justice system, they think of prisons, lengthy sentences, and parole

hearings. They also think of serious offenses such as murder, aggravated assault, and rape. But the majority of

cases are less serious offenses, as defined in statute, including drug possession, shoplifting, gambling, public

drunkenness, disorderly conduct, vandalism, speeding, simple assault, and driving with a suspended license.

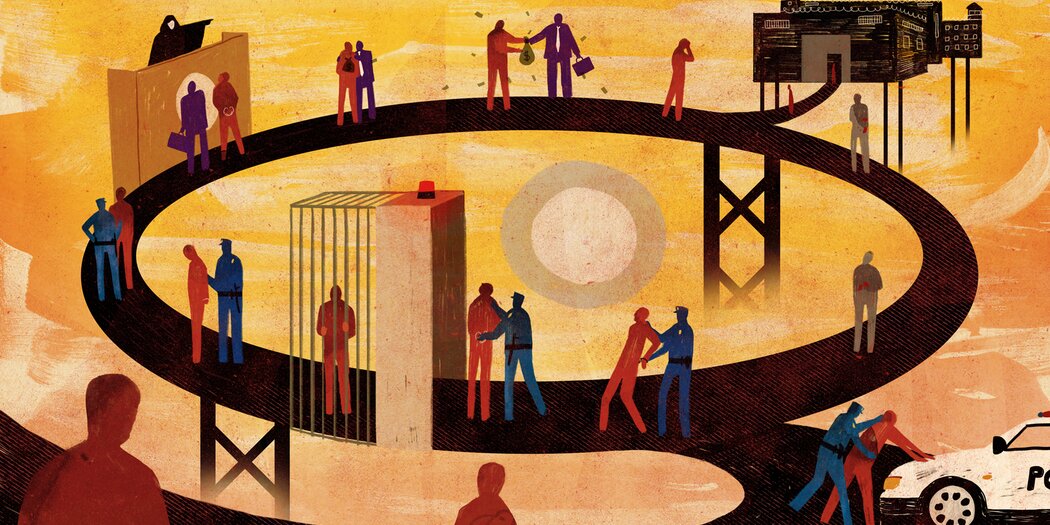

For many Americans, minor offenses — that is, misdemeanors, violations, and infractions — are the primary entry

point into the criminal justice system. Entanglement in this part of the system is anything but minor.

The costs of resolving a case are often high and can require months of court appearances or other compliance

requirements. These obligations take people away from family duties, jobs, and community

responsibilities. Arrests, let alone convictions, can have lifelong consequences, including restricted access to

jobs, places to live, health care, and education.

For example, a 2020 Brennan Center report found that annual earnings for people with a misdemeanor conviction

decrease on average by 16 percent. The harm falls disproportionately on communities of color, many of which

already struggle with concentrated poverty and other forms of social disadvantage.

These mutually reinforcing realities can propel people back into the system.

Despite its broad reach, the minor offense system is difficult to quantify. Government officials often do not collect

data on infractions, civil violations, and other offenses they consider too trivial to count.

The data that is collected — typically data on misdemeanors — is likely an undercount.

Even so, in the United States, misdemeanors amount to roughly three-quarters of all criminal cases filed each year.

Every day, tens of thousands of people are ticketed, arrested, or arraigned for a

misdemeanor, making it a central feature of the United States’ crisis of overcriminalization and an engine of its

overreliance on incarceration.

In recent years, scholars and legal practitioners have brought attention to the need to rein in the sprawling minor

offense system.

Misdemeanor adjudication has earned a reputation of assembly-line justice that lacks meaningful public defense or

due process protections.

Some researchers have described it as a means to mark and manage disadvantaged groups deemed potential risks,

whereby the “process is punishment.” In addition to the degradation of arrest, the imposed obligations and sanctions — frequent court

appearances, the opportunity cost of lost wages, fines and fees, collateral consequences of a criminal record, and

even jail detention — are frequently disproportionate to the severity of the crime.

Minor offense enforcement also consumes an inordinate amount of government resources. Existing estimates for the

policing and court costs of a single misdemeanor offense range from $2,190 to $5,896.

And the overall public safety benefit is questionable. A 2021 study found that on average, people charged with

nonviolent misdemeanors who were not prosecuted were 53 percent less likely to face new criminal charges

than those who were prosecuted. Even more, those without a prior criminal record were 81 percent less likely to

receive a new complaint.

As concern about the minor offense system has grown, efforts to shrink it have proliferated. At the same time,

since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, many people in urban areas have perceived or experienced increased

physical and social disorder in public spaces — petty theft, open drug use, public intoxication, people suffering

mental health crises, homeless encampments, defacement of property, transit fare evasion, and public urination.

Petty and nuisance offenses, visible poverty, and public displays of disorderly and unpredictable behavior, coupled

with high-profile media coverage of violent crimes and harassment, have renewed calls for stronger enforcement of

lower-level offenses.

This report seeks to shed light on minor offense enforcement — what has changed in recent years, what has not, and

what can be done to fix it. Building on previous scholarship, it offers an updated national snapshot of the scale of

misdemeanor cases filed between 2018 and 2021, highlighting changes over the Covid-19 pandemic.

The analysis then homes in on New York City, a jurisdiction at the center of many debates about how to best deploy

finite law enforcement resources to achieve more security and orderliness in public spaces. New York was the

birthplace of “broken windows” policing — a 1990s-era law-and-order strategy based on the idea that police can

mitigate the growth of more serious crime by aggressively targeting minor crimes and violations of public order. But

the city also has a rich history of criminal justice reform, particularly in shrinking unnecessarily punitive

responses to minor offenses.

Such reforms include diversion programs and other alternatives to incarceration, decriminalization of some minor

offenses (e.g., low-level marijuana possession), and crisis response and other restorative strategies for addressing

safety concerns.

Many of these initiatives, though small, may be instructive for other jurisdictions. This study investigates how

efforts to shrink the system changed the enforcement of minor criminal offenses in New York City from 2016 to 2022.

Misdemeanors still compose the bulk of criminal cases filed in New York City — around 75 percent. However, in the

city and across the country, the absolute number of such cases declined across nearly all years under review. This

continued a downward trend from at least 2007 nationwide and from 2010 in New York City. Substantial decreases were observed

in 2020, unsurprising given lockdown orders in many jurisdictions including New York City. Enforcement rebounded in

2021 both nationally and in the city after pandemic restrictions were lifted, though they stayed below 2019 levels.

These trends may reflect important differences in both offending and enforcement patterns.

One troubling pattern, however, remained remarkably stable. Despite reduced unnecessary enforcement and increased use

of more effective alternative responses, profound racial disparities in minor offense cases in New York City proved

stubbornly consistent, as seen elsewhere. Between 2016 and 2022, Black and Latino people made up just under 50 percent of the

city’s population but consistently comprised more than 80 percent of people charged with low-level offenses.

To understand better why racial disparities in enforcement persist in New York City, Brennan Center researchers

engaged police, prosecutors, court officials, city government officials, criminal justice advocates, community-based

service providers, and community leaders impacted by misdemeanor enforcement. Supported by previous research as well

as new Brennan Center data analysis, these stakeholders shed light on the drivers of interactions with the minor

offense system that perpetuate concentrated enforcement among Black and Latino populations in some low-income

communities.

These include social disadvantages such as poverty, housing insecurity, mental illness, and substance use; poor

conditions and a lack of resources in some of those communities; and the criminal justice system’s persistent

inability to address social problems and community needs.

Addressing these complex problems requires looking beyond a simple binary of aggressive enforcement versus inaction.

This report illustrates new data about a shrinking minor offense system, one that also features persistent racial

disparities and geographic concentration in enforcement. The findings are intended to help state and local

policymakers more appropriately deploy resources to reduce crime and build safety and community well-being. Although

rooted in New York City, these findings are applicable to other jurisdictions around the country that aim to

accomplish this goal while eschewing a return to an overly punitive and wasteful approach to enforcement of minor

criminal offenses.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.