Medical equipment manufacturers are refusing to sell their products for use in lethal injection, The Intercept has learned. The stance could further hinder states’ ability to carry out death sentences at a time when similar restrictions have limited access to drugs.

The four companies that have raised objections are Baxter International Inc., B. Braun Medical Inc., Fresenius Kabi, and Johnson & Johnson. In addition to manufacturing drugs, they make IV catheters, syringes, medical tubing, and IV bags, products states rely on to administer lethal injection. In statements to The Intercept, the companies said that the use of their equipment in executions contradicts their values.

“Johnson & Johnson develops medical innovations to save and enhance lives,” Joshina Kapoor, a spokesperson for Johnson & Johnson, wrote in an email. “We do not condone the use of our products for lethal injections for capital punishment.”

Fresenius Kabi, a German company that specializes in IV devices, told The Intercept that it would seize its products from corrections departments if it became aware of their use in lethal injection. B. Braun, which is also headquartered in Germany, said it prohibits its U.S.-based distributors from selling products to prisons for executions. Baxter International, a health care company based in Illinois, confirmed through a spokesperson that a 2017 statement opposing the use of its products in lethal injection applied to medical equipment as well as drugs.

For more than a decade, pharmaceutical companies have forbidden state corrections departments from using their drugs in U.S. execution chambers. The restrictions have led states to track down execution chemicals through unscrupulous suppliers, devise new lethal injection protocols using untested drug combinations, or pursue alternative methods of execution.

But there has been little inquiry into the equipment used to perform lethal injections. The manufacturers’ newly public positions are representative of the growing role private companies are playing in the future of lethal injection and could fuel a new swath of legal challenges as lawyers seek information about the products utilized to kill their clients.

“Once manufacturers and companies find out that their product is being used to kill people, rather than to heal people, they’re concerned, and they don’t want their brand identified with that process,” said Dale Baich, a former federal defender who has represented death row prisoners. “This may be the next step in challenging methods of execution.”

Until now, the bulk of legal challenges to lethal injection have focused on the sources of the drugs and questions about their safety. “It does seem like a natural sort of evolution, that you would start looking at other kinds of things, the manufacturers of the equipment,” Deborah Denno, a death penalty expert and director of Fordham University’s Neuroscience and Law Center, told The Intercept. “Either directly or indirectly, that information may become available.”

Because many states have enacted laws that allow them to conceal the provenance of the equipment employed in executions, it’s unclear whether prison officials are using products from any of the four companies.

Prisons typically buy their medical equipment from wholesalers or distribution companies. To ensure their products don’t end up in the wrong hands, some manufacturers have provisions in their contracts with distributors banning sales for executions. A spokesperson for B. Braun said the company’s contract specifies that its distributors “will not knowingly sell products to any entity that intends to sell or use such products for capital punishment.”

The company reviews its sales records and monitors for misuse, according to the spokesperson. “If we are made aware, we would enforce our rights under our distribution agreements to address any contractual violations and use of our products in an unauthorized manner,” they said.

But it appears that wholesalers may have previously interpreted restrictions more narrowly and applied them solely to drugs, not equipment. In a statement on its website, the medical wholesaler Henry Schein Inc. states that it “restricts the sale or other transfer of medications to prisons/correctional facilities for use in lethal injections, based on our manufacturer agreements.” A spokesperson declined to comment on whether those restrictions include equipment.

McKesson Corp. and Cardinal Health Inc., two of the biggest U.S. medical wholesalers, did not return requests for comment. Both have contracts to provide medical equipment to states that actively employ the death penalty, records show. In 2018, McKesson released a statement declaring that it would decline to sell drugs for lethal injection in compliance with manufacturers’ restrictions. The statement did not discuss its policy on equipment. (The company previously sued Arkansas after officials deceptively purchased a banned drug for executions.)

Notably, McKesson sold IV catheters made by B. Braun to the Oklahoma Department of Corrections between July 2021 and July 2023, purchase records obtained by The Intercept show. The state executed nine people during that period. Kay Thompson, a spokesperson for the Oklahoma corrections department, declined to say whether those catheters were used in executions, stating that the information “cannot be released” because of the state’s secrecy law.

When asked about the purchase records, B. Braun spokesperson Patrick Witmer said the company had confirmed “to the best of our knowledge” that those products were not used for executions. “We are not aware of any other B. Braun products that have been used by the Oklahoma Department of Corrections for capital punishment,” Witmer told The Intercept. He said that as an additional precaution, B. Braun sent letters to Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, Attorney General Gentner Drummond, and the corrections department “affirming the restrictions on the use of B. Braun products for capital punishment.”

Oklahoma has taken secrecy so seriously that Baich, who toured the Oklahoma execution chamber a few years ago, said officials covered the brand name of every product in the room, including the clock and refrigerator. When asked about Baich’s recollection, Thompson replied, “We protect all vendors.”

According to Crystal Chapman, who worked as a nurse at Alabama’s Holman Correctional Facility, the site of the state’s death chamber, the equipment states use in executions does not always come from prison infirmaries, making the products even more difficult to track. Between 2021 and 2022, Chapman was required to maintain an inventory of every item in the infirmary, and although the state executed several people during her tenure, she noticed that nothing was taken. She said she suspected the execution team was responsible for bringing in its own equipment.

“Everything in the infirmary is kept under lock and key,” she said. “And at the end, really, you count every needle, you count every scissor, you count everything. They never go missing, so they don’t use anything from within the facility.”

The Alabama Department of Corrections did not respond to this assertion.

The Intercept asked a dozen corrections departments that have executed people since 2015 to provide details of the equipment they used and respond to manufacturers’ stance against using their products. The corrections departments either declined to comment, often pointing to secrecy laws, or did not answer.

Some say that it’s unlikely that prison officials know they’re not allowed to use certain equipment for executions. “I doubt anyone at the prison would stop to think about that,” said Kelley Henry, a Tennessee federal public defender who works on lethal injection cases. Henry noted that documents she has obtained during discovery in death penalty lawsuits and from public records requests related to execution protocols have not specified restrictions on medical equipment.

The opposition of health care companies to the use of their equipment for capital punishment follows more than a decade of clashes between pharmaceutical companies and state officials seeking to obtain drugs for executions. In 2011, the pharmaceutical company Hospira Inc. (now part of Pfizer Inc.) announced that it would stop production of sodium thiopental, a barbiturate used to induce anesthesia, over concerns the drug would be used for lethal injection. That same year, the European Union voted to prohibit the exportation of drugs used in lethal injection, leading to supply shortages. As part of that rule, the EU created a list of tightly controlled drugs it would not sell to the U.S. That included pentobarbital, which many states also used in executions.

Even as the number of pharmaceutical companies that refused to sell to prison agencies mounted, states continued to find ways to obtain drugs. Missouri, for example, gave an employee $11,000 to travel to neighboring Oklahoma to purchase pentobarbital. Ohio tried to have its department of mental health obtain drugs for use in executions to avoid tracking. In response, lawyers for death row prisoners sought to stop executions over questions about the drugs’ safety.

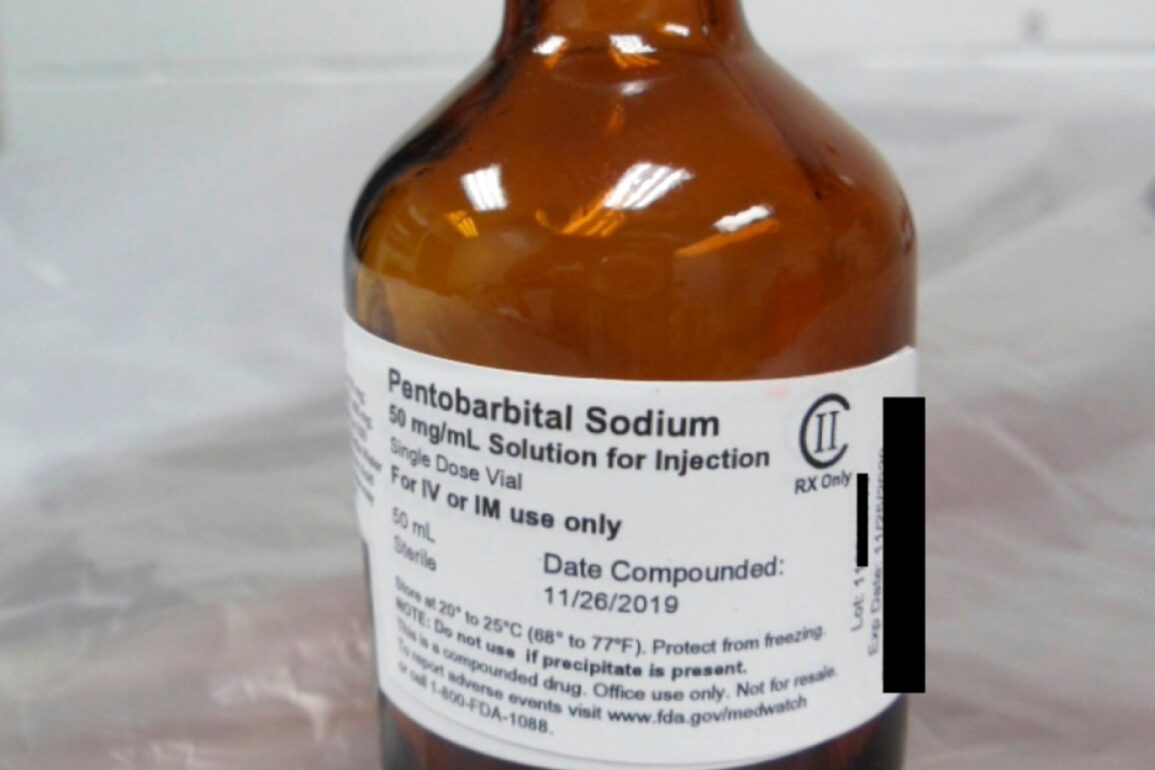

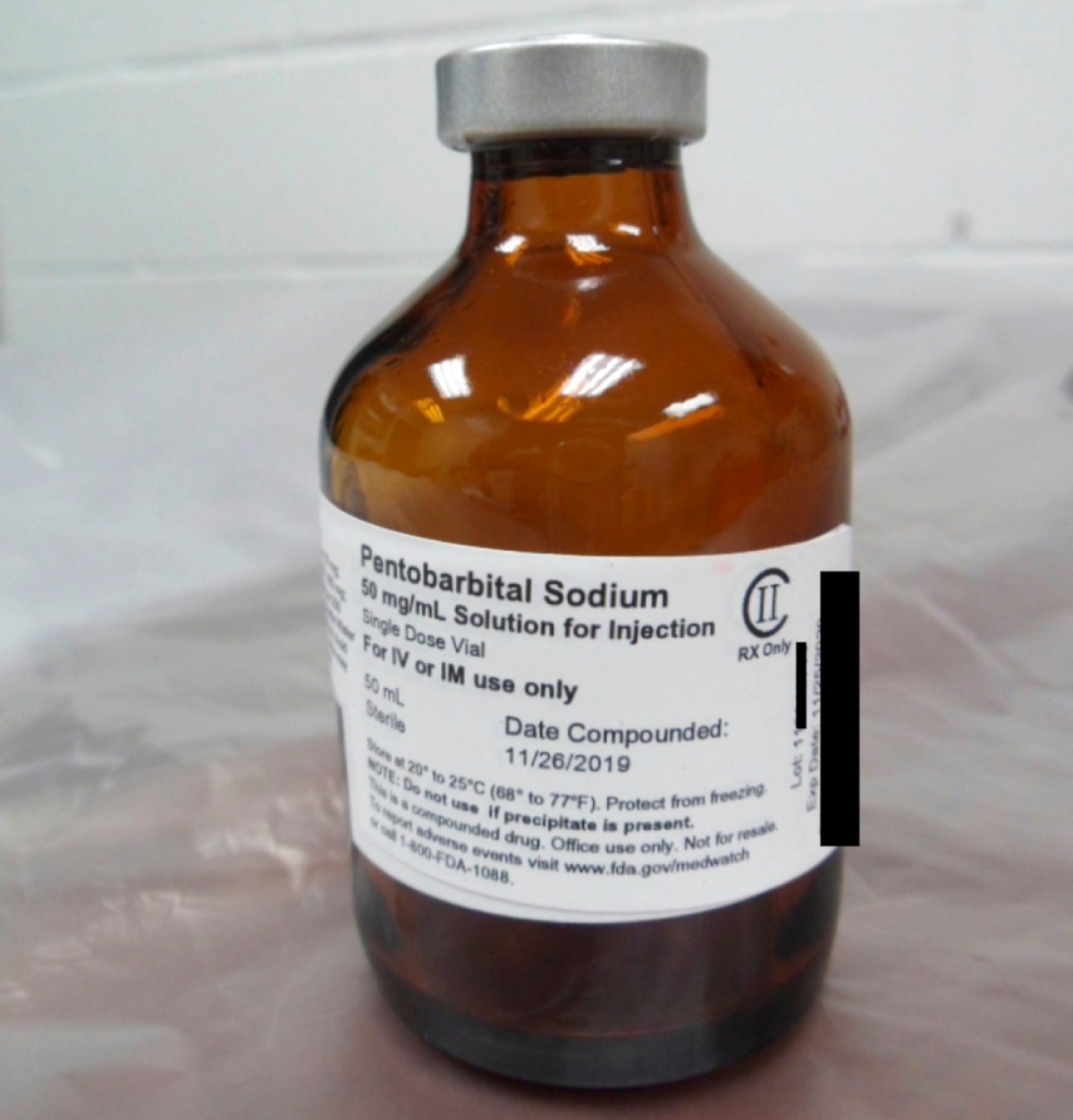

A vial of pentobarbital used in the executions of two people in July 2020. The U.S. government redacted part of the information on the vial to avoid disclosing the drug’s supplier.

In the face of these challenges, some states resorted to making their own drugs through compounding pharmacies, but replicating lethal injection equipment will prove more difficult. “You can’t just compound catheters,” said Joel Zivot, an associate anesthesiology professor at the Emory School of Medicine. “It’s a much harder thing to make.”

Adding to the problem, Zivot said hospitals have experienced shortages of IV equipment since 2014. “Sometimes these products are in short supply. So if the state would actually be able to get their hands on something, and hoard it, something I actually need to treat patients, that just seems to be … untenable,” he said. “These products are for healing and not for killing.”

“These products are for healing and not for killing.”

Over the years, Fresenius Kabi was at the forefront of challenges over the misuse of its products. In 2012, after learning that states were attempting to obtain propofol for executions, it warned that misuse of the drug could lead the EU to impose restrictions on sales to the United States. The medication is an anesthetic administered more than 50 million times each year in the U.S. to sedate patients for medical procedures. In 2018, Fresenius Kabi sued Nebraska for purchasing its drugs for lethal injection.

The company’s spokesperson, Matt Kuhn, told The Intercept that Fresenius Kabi had previously focused on drugs but also told prison officials that its equipment should not be used in lethal injections. (Letters sent to Nebraska officials in 2016 and 2018, which were reviewed by The Intercept, show that while the company stated that officials should not use its products for the purposes of capital punishment, it did not specifically mention medical equipment.) Kuhn said that Fresenius Kabi has not been made aware of any states using its technologies in executions and would take action if needed.

“We would take whatever steps are required to ensure that the product is returned,” Kuhn said. “Depending on how it actually was acquired, we would pursue every option that we have to make sure it doesn’t happen again.”

Manufacturers will likely face an uphill battle in figuring out whether their supplies are being used in executions. Unlike controlled substances, once products such as syringes and IV tubing have been approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration, they’re not closely tracked.

“The FDA does have a certain amount of post-market surveillance, but it’s not going to be really tracking these supplies that are not opioids or some other restricted product,” Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown University’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, told The Intercept. “I think as a practical matter, it’ll be very, very difficult for the company to control who gets access to its products.”

Five states have conducted 17 executions this year, all of them by lethal injection. More than two dozen other executions are planned through the end of 2024.

This story was supported by a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights, in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.