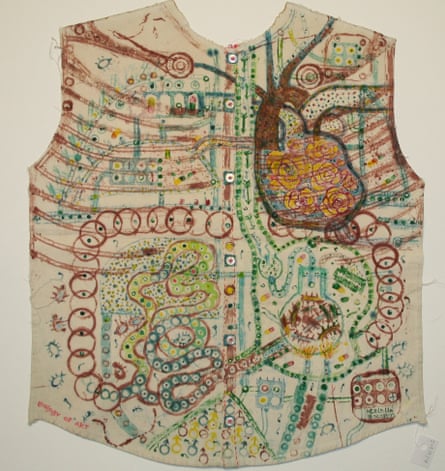

The Burmese painter Htein Lin’s art bears the imprint of his years in a Myanmar jail, where he created hundreds of paintings using prison uniforms as his canvases and makeshift tools including syringes, soap blocks and cigarette lighters.

“I had no canvas, no brushes, no paint. But I had to make art,” says Htein Lin from his home in Myanmar’s Shan state. “I befriended the prison guards to smuggle in paint, scavenging for materials wherever I could.

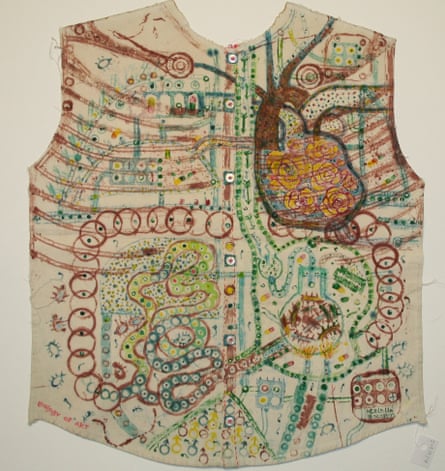

“The prison uniform became my canvas, the wheel of a lighter my ruler, as I repurposed everyday objects as my tools.”

Even after his release, he continued improvising with different techniques.

Htein Lin’s first full retrospective, Escape, at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery, centres on a series of prison paintings, 000235, named after the number assigned to him by the International Committee of the Red Cross during his incarceration in Myanmar from 1998 to 2004.

The exhibition spans the period before his imprisonment, for allegedly plotting opposition protests, through more than six years in jail, seven years in the UK and his life back in Myanmar since then.

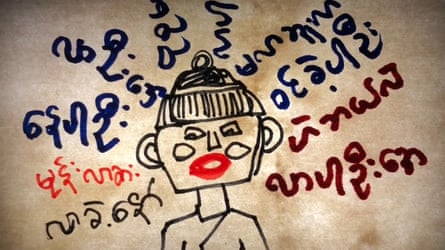

His most recent work includes textile paintings, monoprints, video and performance, while an offsite display at Grendon prison in Buckinghamshire was formed from his collaborations with inmates at the UK prison and its artist-in-residence, Simon Harris.

One of the standout pieces in the 000235 series at the Ikon is Sitting at Iron Gate (2002), which features interlocking limbs and swirling patterns, symbolising “the confined and restricted nature of prison life”.

He describes how he and fellow inmates, often in solitary confinement or small cells, would sit near the prison’s iron gate in the evenings, communicating with each other through songs, poetry and storytelling. “It became our secret to survival,” he says.

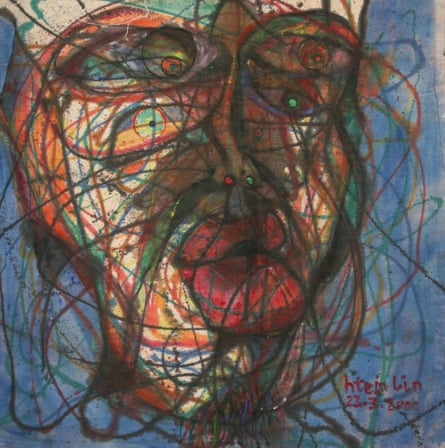

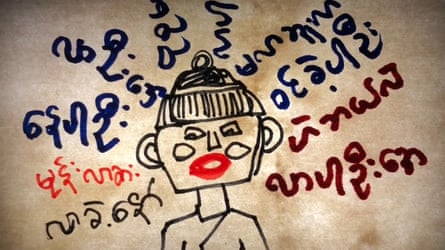

Several self-portraits, painted by the artist using only his fingers, are also on display, along with Biology of Art (1999), which was created using the tops of toothpaste tubes, medical bottles and pill packets.

A series of plaster casts of the hands of former political prisoners, called A Show of Hands, was influenced by the artist’s experience of recovering from a broken arm after a cycling accident.

“Our society was broken, and political prisoners became its strength – like a plaster cast holding fractured bones together,” Htein Lin says.

“It took about half an hour to cast each hand – time in which they recounted their experiences in prison and the story of their sacrifice – I’ve done this for nearly 500 political prisoners.”

Thousands of protesters were arrested during the 1988 pro-democracy uprising and the years that followed. The number of prisoners surged again after the 2021 coup, in which the military seized power from Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratically elected government; more than 28,000 people have reportedly been arrested since the takeover and thousands are still imprisoned, including Aung San Suu Kyi herself.

Born in 1966 in Ingapu, south-west Myanmar, Htein Lin was involved in the 1988 pro-democracy student movement leading to his arrest. He was then given a seven-year prison sentence.

One of his lowest points came in Mandalay jail, where he was held from 1998 to 2000. “They handcuffed me, blindfolded me, and took me out of the cell,” he recalls.

“I couldn’t see who was beating me, but they lined us up and we had to walk between two rows of guards who struck us from both sides.”

after newsletter promotion

It was the art he created that got him through the toughest times. “I spent long stretches in solitary confinement, yet making art made me feel completely free.

“Painting wasn’t officially allowed – neither was reading or writing – so every brushstroke was a risk. But I knew my art had to reflect what was happening in my country.”

During his time in prison, Htein Lin produced about 1,000 paintings and drawings, managing to smuggle many of them out. About 230 paintings survive, with many now held at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam.

The 58-year-old artist is unable to attend his solo show in Birmingham because he cannot get a passport. In 2022, he and his wife, Vicky Bowman – Britain’s ambassador to Myanmar from 2002 to 2006 – were sentenced to a year in prison by the military junta for allegedly failing to register their new address, although they suspect the real motivation was Bowman’s work on corporate transparency.

Though they were released after three months, Bowman was then deported. Htein Lin has had to remain in Myanmar as the authorities refuse to renew his passport. The couple have been separated for two years.

“After my release in 2004, I never thought I’d end up in prison again,” he says, “but history repeats itself.”

Reflecting on the escalating situation in Myanmar, Htein Lin notes that the conflict is far more intense than previous uprisings.

“Most of my work is reacting to, and reflecting on, what is happening,” he says about his 2024 painting Fiery Hell, inspired by the devastation wreaked by the civil war. Htein Lin believes the world largely ignores the crisis.

“It’s not that the world misunderstands Myanmar – it’s that the world doesn’t pay attention.”

Meditation, including the Burmese Buddhist “bare insight” vipassana practice, has helped him navigate the most difficult times. He has also mastered the art of waiting, believing that even in the darkest times, transformation is possible.

“I have become very good at waiting. One day, I will get my passport back. One day, things will change.”

-

Escape is at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham until 1 June

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.